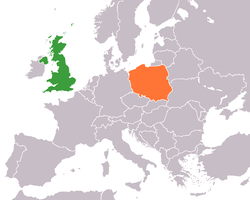

Poland–United Kingdom relations

|

|

United Kingdom |

Poland |

|---|---|

British–Polish relations are the foreign relations between the United Kingdom and Poland.

Background

8th and 9th centuries

Polish–British relations have existed in one form or another since the 8th century. According to medieval tradition and relations, King Cnut (or Canute) the Great, King of England, Denmark and Norway (ruled England between 1016 and 1035) had a mother of unknown identity, but it was found that his mother was a daughter of the first (unofficially crowned) King of Poland, Mieszko I, which makes Mieszko I of Poland the grandfather of King Cnut the Great.

15th century

According to Polish historian Oskar Halecki, there was a piece of correspondence by King Henry V of England to Władysław II Jagiełło, King of Poland and Grand-Duke of Lithuania, requesting his assistance against France in the Hundred Years' War.[1] British–Polish relations had continued in the following years largely in the area of commerce, and diplomacy. The 16th century saw the height of early modern diplomatic relations between Poland and England. When Queen Mary I of England and King Philip II of Spain were married in 1554, Krzysztof Warszewicki was present to attend and witness their wedding. Warszewicki was, at the time of the Tudor-Habsburg marriage, page to Ferdinand, King of the Romans. According to Norman Davies, Warszewicki later became a notable Polish diplomat.

After the death of Queen Mary I, her sister Elizabeth ascended to the English throne. Unlike her Catholic sister, Queen Elizabeth I was a Protestant and she gave her support to the Dutch cause against their Spanish Habsburg overlords. With the English and the Dutch at war with the Spaniards, the conflict adversely affected the Spanish trade with the Polish port city of Gdańsk as British and Dutch navies and privateers would seize Spanish vessels, including those sailing for Poland. Poland and, by extension, the city of Gdańsk sent Paweł Działyński to the Dutch and the English, persuading them to stop their attacks against Spanish ships headed for Gdańsk. However, as Norman Davies writes, Działyński was overly direct and blunt, threatening the Dutch and the English with an embargo of their merchants and goods. Queen Elizabeth I responded with an equally blunt response and Działyński’s mission ultimately failed.

In the 17th century, twenty Scottish traders formed the foundation of a successful Scottish colony in Poland. These Scots were referred by Norman Davies as "British Trading Agents".

18th century

As the 18th century dawned, the sun was setting slowly over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Saxon Kings of Poland-Lithuania had largely neglected Poland’s diplomatic relations during this period, as they preferred to conduct their diplomatic affairs from Saxony. This, however, did not stop the conducting of diplomatic relations with other European states. In 1744, the British Government concluded negotiations in a treaty between Britain, the Netherlands, Hungary, and Poland. The multilateral agreement, which the Journal of the House of Commons calls “Treaty of Friendship and Alliance”, comes during the War of the Austrian Succession in which Britain fought on the side of Maria Theresa of Austria, the Queen of Hungary. Poland was a neutral power in the war and did not participate. However, as Saxony was a participant and the Elector of Saxony was the King of Poland, the treaty was signed and ratified in the name of the "Polish Republic".

With the death of Augustus III in late 1762, a certain Stanisław August Poniatowski was elected to the Polish Throne at the end of 1764. Although King George III mentioned the election of Stanisław August Poniatowski in His Majesty’s most gracious speech to Parliament in 1765, his speeches to Parliament in 1772 and 1773 made no references to the 1772 Partition of Poland by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. The King does not mention the Second Partition in his 1793 speech to Parliament, nor does His Majesty mention the Third and Final Partition in his 1795 speech to Parliament. In reaction to the decision of His Majesty’s Government to make no diplomatic protests against the actions of Russia, Prussia, and Austria, Britain’s 18th and 19th century contemporaries on the European continent and scholars of Polish history have often made the following conclusion: Britain was indifferent to the situation in Poland.

Although Britain seemed to be large indifferent to the Partition of Poland, many of Britain's political elites, including King George III and Edmund Burke, did voice their concerns in their correspondences and publications about the Partitions and the imbalance of power in Europe it created.

19th century

During the Congress of Vienna, Lord Castlereagh, British Foreign Secretary from 1812 to 1822, was a major proponent of restoration of Polish independence, although he later dropped this point to attain ground in areas on which Britain had greater interest.

During the 19th century frosty British–Russian relations prompted more of an interest in an independent Poland from Britain. Amongst the British populace too sympathy for Poland and the other oppressed peoples of Europe was popular.

20th century

During the Polish–Soviet war the support of the British government was truly with Poland, but peace was by far the preferred option resulting in Lord Curzon's drawing of the Curzon Line as part of an attempted mediated peace. This agreement was not adopted in time and Poland soon took the upper hand in the war pushing its border further to the east.

During the 1920s and early 1930s British views of Poland were generally negative due to its expansionism and treatment of ethnic minorities. This was particularly the case from the British left. The right wing in Britain meanwhile held more overall neutral views of Poland due to its position as a buffer against communism.

Poland's view of Britain at this time was generally ambivalent; France or even Germany being the primary focus of their friendship and attempts to gain protection. The first Polish embassy in London was established only in 1929.

With the rise of the Nazi party in Germany the two countries began to see more of a point in friendly relations. On the 31 March 1939 the UK made a guarantee of independence to Poland. On the 25th of August an Anglo-Polish military alliance was signed. At first glance this treaty was just a catch-all mutual assistance pact against the aggression of any other European nation however a secret protocol attached to the agreement made clear this was Germany.

Second World War

In September, following the German invasion of Poland, Britain (and France) declared war against Germany starting World War II but no direct military assistance, and broke the treaty which Churchill had signed, was brought against Germany in the short time before Poland fell (so-called Phoney War).

During the war 250,000 Polish people served with British forces taking part in many key campaigns. 1/12 of all pilots in the Battle of Britain were Polish.

During the Yalta conference and subsequent post-war alteration of Poland's borders British-Polish relations hit a low due to Britain's compromising over Poland's fate so readily. Poland saw this in a particularly negative light due to their large contribution to the war effort and the sacrifices they had made.

Post-war many Polish servicemen remained in Britain and further numbers of refugees arrived in the country.

Cold War

At first British relations to communist Poland were largely neutral with some sections of the far left even being supportive of the regime. The Polish government in exile from during the war at 43 Eaton Place in London remained in place, however, and no Poles were forced to return home.

During the cold war Poland retained a largely negative view of Britain as part of the west. British efforts meanwhile were focused at trying to break Poland off from the Warsaw Pact and encouraging reforms in the country.

Post-Cold War

In the 1990s and 2000s democratic Poland has maintained close relations with Britain; both in defence matters and within the EU; Britain being one of only a few countries allowing equal rights to Polish workers upon their accession in 2004. 375 000 Poles have registered to work in the UK after the EU accession.

The results of the 2011 national census has shown that Polish is now the second most common spoken first language in Northern Ireland after English, surpassing Ulster Scots and Irish.

Twinnings

Footnotes

- ↑ Halecki, Oskar (1934). "Anglo-Polish Relations in the Past". The Slavonic and East European Review. 12 (36): 660.

Further reading

- Horn, David Bayne. Great Britain and Europe in the eighteenth century (1967), covers 1603 to 1702; pp 201-36.

- Kaiser, David E. Economic Diplomacy and the Origins of the Second World War: Germany, Britain, France, and Eastern Europe, 1930-1939 (Princeton UP, 2015).

Sources

- The New Atlanticist: Poland’s Foreign and Security Policy Priorities, pp. 80–84, by Kerry Longhurst and Marcin Zaborowski, from The Royal Institute of International Affairs, first published 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd., ISBN 978-1-4051-2646-5 (hardback), ISBN 978-1-4051-2645-8 (paperback).

- Cnut the Great

- Mieszko I of Poland

See also

- List of Ambassadors from the United Kingdom to Poland

- List of Ambassadors of Poland to the United Kingdom

- Anglo-Polish Radio ORLA.fm Reports on Anglo-Polish relations, Poland–United Kingdom relations http://www.orla.fm