Christianity in the 3rd century

Upper tier: dedication to the Dis Manibus and Christian motto in Greek letters ΙΧΘΥC ΖΩΝΤΩΝ: Ikhthus zōntōn, "fish of the living"; middle tier: depiction of fish and an anchor; lower tier: Latin inscription "LICINIAE FAMIATI BE / NE MERENTI VIXIT".

Christianity in the 3rd century was largely the time of the Ante-Nicene Fathers who wrote after the Apostolic Fathers of the 1st and 2nd centuries but before the First Council of Nicaea in 325 (ante-nicene meaning before Nicaea).

As the Roman Empire experienced the Crisis of the Third Century, the emperor Decius enacted measures intended to restore stability and unity, including a requirement that Roman citizens affirm their loyalty through religious ceremonies pertaining to Imperial cult. In 212, universal citizenship had been granted to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire, and with the edict of Decius enforcing religious conformity in 250, Christian citizens faced an intractable conflict: any citizen who refused to participate in the empire-wide supplicatio was subject to the death penalty.[1] Although lasting only a year,[2] the Decian persecution was a severe departure from previous imperial policy that Christians were not to be sought out and prosecuted as inherently disloyal.[3] Even under Decius, orthodox Christians were subject to arrest only for their refusal to participate in Roman civic religion, and were not prohibited from assembling for worship. Gnostics seem not to have been persecuted.[4]

Christianity flourished during the four decades known as the "Little Peace of the Church", beginning with the reign of Gallienus (253–268), who issued the first official edict of tolerance regarding Christianity.[5] The era of coexistence ended when Diocletian launched the final and "Great" Persecution in 303.

Early Christianity

Defining scripture

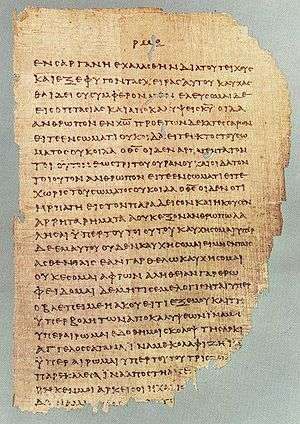

The Biblical canon began with the officially accepted books of the Koine Greek Old Testament. The Septuagint or seventy is accepted as the foundation of the Christian faith along with the Gospels, Book of Revelation and Letters of the Apostles (including Acts of the Apostles and the Epistle to the Hebrews) of the New Testament.

By the early 200's, Origen of Alexandria may have been using the same 27 books as in the modern New Testament, though there were still disputes over the canonicity of Hebrews, James, II Peter, II John and III John, and Revelation,[6] referred to as the Antilegomena.

Heresies

The letters accepted by many Christians as part of Scripture warned about mixing Judaism with Christianity, leading to decisions reached in the first ecumenical council, which was convoked by Emperor Constantine at Nicaea in 325 in response to further disruptive polemical controversy within the Christian community, in that case Arian disputes over the nature of the Trinity. Before 325, the "heretical" nature of some beliefs was a matter of much debate within the churches. After 325, some opinion was formulated as dogma through the canons promulgated by the councils.

Early iconography

Christian art emerged only relatively late. According to art historian André Grabar, the first known Christian images emerge from about AD 200,[8] though there is some literary evidence that small domestic images were used earlier. Although many Hellenised Jews seem, as at the Dura-Europos synagogue, to have had images of religious figures, the traditional Mosaic prohibition of "graven images" no doubt retained some effect. This early rejection of images, although never proclaimed by theologians, and the necessity to hide Christian practise from persecution, leaves few archaeological records regarding Early Christianity and its evolution.[9] The oldest Christian paintings are from the Roman Catacombs, dated to about 200, and the oldest Christian sculptures are from sarcophagi, dating to the beginning of the 3rd century.[9]

Monasticism

Institutional Christian monasticism seems to have begun in the deserts in 3rd century Egypt as a kind of living martyrdom. Anthony of Egypt (251-356) is the best known of these early hermit-monks. Anthony the Great and Pachomius were early monastic innovators in Egypt, although Paul the Hermit is the first Christian historically known to have been living as a monk. Eastern Orthodoxy looks to Basil of Caesarea as a founding monastic legislator, as well to as the example of the Desert Fathers. Shortly after 360 Martin of Tours introduced monasticism to the west. Benedict of Nursia, who lived a century later, established the Rule that led to him being credited with the title of father of western monasticism. Scholars such as Lester K. Little attribute the rise of monasticism at this time to the immense changes in the church brought about by Constantine's legalization of Christianity. The subsequent transformation of Christianity into the main Roman religion ended the position of Christians as a small group. In response, a new more advanced form of dedication was developed. The long-term "martyrdom" of the ascetic replaced the violent physical martyrdom of the persecutions. Others point to historical evidence that individuals were living the life later known as monasticism before the legalization of Christianity.In fact it is believed by the Carmelites that they were started by the Jewish prophet Elias.

From the earliest times there were probably individual hermits who lived a life in isolation in imitation of Jesus' 40 days in the desert. They have left no confirmed archaeological traces and only hints in the written record. Communities of virgins who had consecrated themselves to Christ are found at least as far back as the 2nd century. There were also individual ascetics, known as the "devout," who usually lived not in the deserts but on the edge of inhabited places, still remaining in the world but practicing asceticism and striving for union with God. Anthony the Great was the first to specifically leave the world and live in the desert as a monk.[10] Anthony lived as a hermit in the desert and gradually gained followers who lived as hermits nearby but not in actual community with him. One such, Paul the Hermit, lived in absolute solitude not very far from Anthony and was looked upon even by Anthony as a perfect monk. This type of monasticism is called eremitical or "hermit-like."

As monasticism spread in the East from the hermits living in the deserts of Egypt to Palestine, Syria, and on up into Asia Minor and beyond, the sayings (apophthegmata) and acts (praxeis) of the Desert Fathers came to be recorded and circulated, first among their fellow monastics and then among the laity as well. Among these earliest recorded accounts was the Paradise, by Palladius of Galatia, Bishop of Helenopolis (also known as the Lausiac History, after the prefect Lausus, to whom it was addressed). Athanasius of Alexandria (whose Life of Saint Anthony the Great set the pattern for monastic hagiography), Jerome, and other anonymous compilers were also responsible for setting down very influential accounts. Also of great importance are the writings surrounding the communities founded by Pachomius, the father of cenobiticism, and his disciple Theodorus of Tabennese, the founder of the skete form of monasticism.

Ante-Nicene Fathers

As Christianity spread, it acquired certain members from well-educated circles of the Hellenistic world; they sometimes became bishops but not always. They produced two sorts of works: theological and "apologetic", the latter being works aimed at defending the faith by using reason to refute arguments against the veracity of Christianity. These authors are known as the Church Fathers, and study of them is called Patristics. Notable early Fathers include Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen

Much theological reflection emerged in the early centuries of the Christian church – in a wide variety of genres, in a variety of contexts, and in several languages – much of it the ich it was born. So, for instance, a good deal of the Greek language literature can be read as an attempt to come to terms with Hellenistic culture. Examples are the emergence of orthodoxy (the idea of which seems to emerge from the conflicts between proto-orthodox Christianity and Gnosticism and Marcionism), the establishment of a Biblical canon, debates about the doctrine of the Trinity (most notably between the councils of Nicaea in 325 and Constantinople in 381), about Christology (most notably between the councils of Constantinople in 381 and Chalcedon in 451), about the purity of the Church (for instance in the debates surrounding the Donatists), and about grace, free will and predestination (for instance in the debate between Augustine of Hippo and Pelagius).

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, or Fathers of the Church are the early and influential theologians and writers in the Christian Church, particularly those of the first five centuries of Christian history. The term is used of writers and teachers of the Church, not necessarily saints. Teachers particularly are also known as doctors of the Church, although Athanasius called them men of little intellect.[11]

Greek Fathers

Those who wrote in Greek are called the Greek (Church) Fathers.

Clement of Alexandria

Clement of Alexandria (Titus Flavius Clemens) was the first member of the Church of Alexandria to be more than a name, and one of its most distinguished teachers. He united Greek philosophical traditions with Christian doctrine and valued gnosis that with communion for all people could be held by common Christians. He developed a Christian Platonism.[12] Like Origen, he arose from Catechetical School of Alexandria and was well versed in pagan literature.[12]

Origen of Alexandria

Origen was an early Christian scholar and theologian. According to tradition, he was an Egyptian[13] who taught in Alexandria, reviving the Catechetical School where Clement had taught. The patriarch of Alexandria at first supported Origen but later expelled him for being ordained without the patriarch's permission. He relocated to Caesarea Maritima and died there[14] after being tortured during a persecution.

Using his knowledge of Hebrew, he produced a corrected Septuagint.[12] He wrote commentaries on all the books of the Bible.[12] In Peri Archon (First Principles), he articulated the first philosophical exposition of Christian doctrine.[12] He interpreted scripture allegorically and showed himself to be a Stoic, a Neo-Pythagorean, a and Platonic.[12] Like Plotinus, he wrote that the soul passes through successive stages before incarnation as a human and after death, eventually reaching God.[12] He imagined even demons being reunited with God. For Origen, God was not Yahweh but the First Principle, and Christ, the Logos, was subordinate to him.[12] His views of a hierarchical structure in the Trinity, the temporality of matter, "the fabulous preexistence of souls," and "the monstrous restoration which follows from it" were declared anathema in the 6th century.[15][16]

Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome was one of the most prolific writers of early Christianity. Hippolytus was born during the second half of the 2nd century, probably in Rome. Photius describes him in his Bibliotheca (cod. 121) as a disciple of Irenaeus, who was said to be a disciple of Polycarp, and from the context of this passage it is supposed that he suggested that Hippolytus so styled himself. However, this assertion is doubtful.[17] He came into conflict with the Popes of his time and for some time headed a separate group. For that reason he is sometimes considered the first Antipope. However he died in 235 or 236 reconciled to the Church and as a martyr.

Latin Fathers

Those fathers who wrote in Latin are called the Latin (Church) Fathers.

Tertullian

Tertullian, who was converted to Christianity before 197, was a prolific writer of apologetic, theological, controversial and ascetic works.[18] He was the son of a Roman centurion.

Tertullian denounced Christian doctrines he considered heretical, but it has been claimed that later in life he converted to Montanism, a heretical sect that appealed to his rigorism.[18] He wrote three books in Greek and was the first great writer of Latin Christianity, thus sometimes known as the "Father of the Latin Church".[19] He was evidently a lawyer in Rome.[20] He is said to have introduced the Latin term "trinitas" with regard to the Divine (Trinity) to the Christian vocabulary[21] (but Theophilus of Antioch already wrote of "the Trinity, of God, and His Word, and His wisdom", which is similar but not identical to the Trinitarian wording),[22] and also probably the formula "three Persons, one Substance" as the Latin "tres Personae, una Substantia" (from the Koine Greek "treis Hypostases, Homoousios"), and also the terms "vetus testamentum" (Old Testament) and "novum testamentum" (New Testament).

In his Apologeticus, he was the first Latin author who qualified Christianity as the "vera religio" and systematically relegated the classical Roman Empire religion and other accepted cults to the position of mere "superstitions".

Cyprian of Carthage

Cyprian was bishop of Carthage and an important early Christian writer. He was probably born at the beginning of the 3rd century in North Africa, perhaps at Carthage, where he received an excellent classical education. After converting to Christianity, he became a bishop in 249 and eventually died a martyr at Carthage.

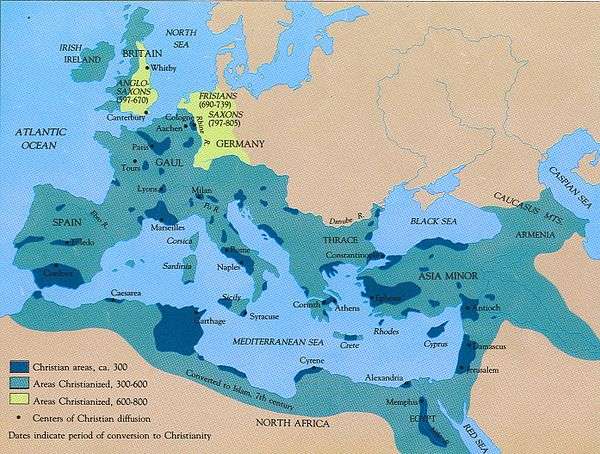

Spread of Christianity

Goths

In the 3rd century, East-Germanic peoples migrated into Scythia. Gothic culture and identity emerged from various East-Germanic, local, and Roman influences. In the same period, Gothic raiders took captives among the Romans, including many Christians.

Precursor to the Great Schism

Leading to the Great Schism, Eastern and Western Mediterranean Christians had a history of differences and disagreements dating to the 2nd century.[23] Among the most significant disagreement was the Rebaptism controversy at the time of Stephen of Rome and Cyprian of Carthage (250s).

- 202 - Roman Emperor Severus issues an edict forbidding conversion to Christianity [24]

- 206 - Abgar, King of Edessa, embraces the Christian faith [25]

- 185-350? Muratorian fragment, 1st extant canon for New Testament after Marcion?, written in Rome by Hippolytus?, excludes Hebrews, James, 1-2 Peter, 3 John; includes Wisdom of Solomon, Apocalypse of Peter

- 188-231 Saint Demetrius, bishop of Alexandria, condemned Origen

- 199-217? Caius , presbyter of Rome, wrote "Dialogue against Proclus" in Ante-Nicene Fathers, rejected Revelation, said to be by Gnostic Cerinthus, see also Alogi

- 208 - Tertullian writes that Christ has followers on the far side of the Roman wall in Britain where Roman legions have not yet penetrated [26]

- 220? Clement of Alexandria, cited "Alexandrian" NT text-type & Secret Gospel of Mark & Gospel of the Egyptians; wrote: "Exhortations to the Greeks"; "Rich Man's Salutation"; "To the Newly Baptized"; (Ante-Nicene Fathers)

- 217-236 Antipope Hippolytus, Logos sect?

- 218-258 Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, cited "Western" NT text-type, claimed Christians were freely forging his letters to discredit him (Ante-Nicene Fathers)

- 241 - Mani begins to preach in Seleucia-Ctesiphon in what is now Iraq

- 250 - Denis (or Denys or Dionysius) is sent from Rome along with six other missionaries to establish the church in Paris [27]

- 223? Tertullian, sometimes called "father of the Latin Church" because he coined trinitas, tres Personae, una Substantia, Vetus Testamentum, Novum Testamentum, convert to Montanism, cited "Western" Gospel text-type (Ante-Nicene Fathers)

- 225? Papyrus 45: 1st Chester Beatty Papyri, Gospels (Caesarean text-type, mixed), Acts (Alexandrian text-type)

- 235-238 Maximinus Thrax, emperor of Rome, ends Christian schism in Rome by deporting Pope Pontian and Antipope Hippolytus to Sardinia where they soon die

- 248-264 Dionysius, Patriarch of Alexandria see also List of Patriarchs of Alexandria

- 250? Apostolic Constitutions, Liturgy of St James, Old Roman Symbol, Clementine literature

- 250? Letters of Methodius, Pistis Sophia, Porphyry Tyrius, Commodianus (Ante-Nicene Fathers)

- 250? Papyrus 72: Bodmer 5-11+, pub. 1959, "Alexandrian" text-type: Nativity of Mary; 3Cor; Odes of Solomon 11; Jude 1-25; Melito's Homily on Passover; Hymn fragment; Apology of Phileas; Ps33,34; 1Pt1:1-5:14; 2Pt1:1-3:18

- 250? Origen, Jesus and God one substance, adopted at First Council of Nicaea in 325, compiled Hexapla; cites Alexandrian, Caesarean text-type; Eusebius claimed Origen castrated himself for Christ due to Mt19:12 (EH6.8.1-3)

- 251-258 Antipope Novatian, decreed no forgiveness for sins after baptism

- 254-257 Pope Stephen I; major schism over rebaptizing heretics and apostates

- 258 "Valerian's Massacre": Roman emperor issued edict to execute immediately all Christian Bishops, Presbyters, and Deacons, including Pope Sixtus II, Antipope Novatian, Cyprian of Carthage (CE: Valerian, Schaff's History Vol 2 Chap 2 § 22)

- 264-269 Synods of Antioch, condemned Paul of Samosata, Bishop of Antioch, founder of Adoptionism (Jesus was human until Holy Spirit descended at his baptism), also condemned term homoousios adopted at Nicaea

- 265 Gregory Thaumaturgus (Ante-Nicene Fathers)

- 270? Anthony begins monastic movement

- 270 - Death of Gregory Thaumaturgus, Christian leader in Pontus. It was said that when Gregory became "bishop" there were only 17 Christians in Pontus while at his death thirty years later there were only 17 non-Christians.[28]

- 275? Papyrus 47: 3rd Chester Beatty, ~Sinaiticus, Rev9:10-11:3,5-16:15,17-17:2

- 276 Mani (prophet), crucified, founder of the dualistic Manichaean sect in Persia

- 220?-340? Codex Tchacos, manuscript containing a copy of the Gospel of Judas has been written.

- 280 - First rural churches emerge in northern Italy; Christianity is no longer exclusively in urban areas

- 287 - Maurice from Egypt is killed at Agauno, Switzerland for refusing to sacrifice to pagan divinities [29]

- 282-300? Theonas, bishop of Alexandria (Ante-Nicene Fathers)

- 300 - First Christians reported in Greater Khorasan; an estimated 10% of the world's population is now Christian; parts of the Bible are available in 10 different languages [30]

See also

- History of Christianity

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Christian theology

- Christian martyrs

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- History of early Christianity

- Ante-Nicene Period

- Church Fathers

- List of Church Fathers

- Christian monasticism

- Patristics

- Great Church

- Split of early Christianity and Judaism

- Development of the New Testament canon

- Christianization

- History of Calvinist-Arminian debate

- List of events in early Christianity

- Timeline of Christianity

- Timeline of Christian missions

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church

- Chronological list of saints in the 3rd century

Notes

- ↑ Allen Brent, Cyprian and Roman Carthage (Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 193ff. et passim; G.E.M. de Ste. Croix, Christian Persecution, Martyrdom, and Orthodoxy, edited by Michael Whitby and Joseph Streeter (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 59.

- ↑ Ste. Croix, Christian Persecution, Martyrdom, and Orthodoxy, p. 107.

- ↑ Ste. Croix, Christian Persecution, Martyrdom, and Orthodoxy, p. 40.

- ↑ Ste. Croix, Christian Persecution, Martyrdom, and Orthodoxy, pp. 139–140

- ↑ Françoise Monfrin, entry on "Milan," p. 986, and Charles Pietri, entry on "Persecutions," p. 1156, in The Papacy: An Encyclopedia, edited by Philippe Levillain (Routlege, 2002, originally published in French 1994), vol. 2; Kevin Butcher, Roman Syria and the Near East (Getty Publications, 2003), p. 378.

- ↑ Noll, pp.36-37

- ↑ "The figure (…) is an allegory of Christ as the shepherd" André Grabar, "Christian iconography, a study of its origins", ISBN 0-691-01830-8

- ↑ Andre Grabar, p.7

- 1 2 Grabar, p.7

- ↑ Paul of Thebes had gone into the desert before Anthony; however, he went not for the purpose of pursuing God but to escape persecution.

- ↑ Athanasius, On the Incarnation 47

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Will Durant. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972, ISBN 1-56731-014-1

- ↑ George Sarton (1936). "The Unity and Diversity of the Mediterranean World", Osiris 2, p. 406-463 [430].

- ↑ About Caesarea

- ↑ The Anathemas Against Origen, by the Fifth Ecumenical Council (Schaff, Philip, "The Seven Ecumenical Councils", Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 2, Vol. 14. Edinburgh: T&T Clark)

- ↑ The Anathematisms of the Emperor Justinian Against Origen (Schaff, op. cit.)

- ↑ Cross, F. L., ed., "The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church" (Oxford University Press 2005)

- 1 2 Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005, article Tertullian

- ↑ Vincent of Lerins in 434AD, Commonitorium, 17, describes Tertullian as 'first of us among the Latins' (Quasten IV, p.549)

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia: Tertullian

- ↑ A History of Christian Thought, Paul Tillich, Touchstone Books, 1972. ISBN 0-671-21426-8 (p. 43)

- ↑ To Autolycus, Book 2, chapter XV

- ↑ Cleenewerck, Laurent His Broken Body: Understanding and Healing the Schism between the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. Washington, DC: EUC Press (2008) pp. 145-155

- ↑ Latourette, 1941, vol. I, 145

- ↑ Herbermann, p. 282

- ↑ Neill, p. 31

- ↑ Herbermann, p. 481

- ↑ Latourette, 1941, vol. I, p. 89

- ↑ Walsh, Martin de Porres. The Ancient Black Christians, Julian Richardson Associates, 1969, p. 5

- ↑ Barrett, p. 24

References

- Noll, Mark A., Turning Points, Baker Academic, 1997

Further reading

- Edwards, Mark (2009). Catholicity and Heresy in the Early Church. Ashgate.

- Esler, Philip F. The Early Christian World. Routledge (2004). ISBN 0-415-33312-1.

- Fletcher, Richard. The Conversion of Europe. From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD. University of California Press (1997).

- von Padberg, Lutz E. Die Christianisierung Europas im Mittelalter. Reclam (2008).

- Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan. The Christian Tradition, Volume One: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600). University of Chicago Press (1975). ISBN 0-226-65371-4.

- Russell, James C. The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity: A Sociohistorical Approach to Religious Transformation. Oxford University Press (1994). ISBN 0-19-510466-8.

- MacMullen, Ramsay. Christianizing the Roman Empire, AD 100-400. Yale University Press (1986). ISBN 0-300-03642-6

- Trombley, Frank R. Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370-529. Brill (1995). ISBN 90-04-09691-4

- White, L. Michael. From Jesus to Christianity. HarperCollins (2004). ISBN 0-06-052655-6.

External links

- Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins

- Guide to Early Church Documents

- Chart of Church Fathers at ReligionFacts.com

- Church Fathers' works in English edited by Philip Schaff, at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- Church Fathers at Newadvent.org

- Faulkner University Patristics Project A growing collection of English translations of patristic texts and high-resolution scans from the comprehensive Patrologia compiled by J. P. Migne.

- Primer on the Church Fathers at Corunum