Olive oil

|

Extra-virgin olive oil presented with green and black preserved table olives | |

| Fat composition | |

|---|---|

| Saturated fats | |

| Total saturated |

Palmitic acid: 13.0% Stearic acid: 1.5% |

| Unsaturated fats | |

| Total unsaturated | > 85% |

| Monounsaturated |

Oleic acid: 70.0% Palmitoleic acid: 0.3–3.5% |

| Polyunsaturated |

Linoleic acid: 15.0% α-Linolenic acid: 0.5% |

| Properties | |

| Food energy per 100 g (3.5 oz) | 3,700 kJ (880 kcal) |

| Melting point | −6.0 °C (21.2 °F) |

| Boiling point | 300 °C (572 °F) |

| Smoke point |

190 °C (374 °F) (virgin) 210 °C (410 °F) (refined) |

| Specific gravity at 20 °C (68 °F) | 0.911[1] |

| Viscosity at 20 °C (68 °F) | 84 cP |

| Refractive index |

1.4677–1.4705 (virgin and refined) 1.4680–1.4707 (pomace) |

| Iodine value |

75–94 (virgin and refined) 75–92 (pomace) |

| Acid value |

maximum: 6.6 (refined and pomace) 0.8 (extra-virgin) |

| Saponification value |

184–196 (virgin and refined) 182–193 (pomace) |

| Peroxide value |

20 (virgin) 10 (refined and pomace) |

Olive oil is a fat obtained from the olive (the fruit of Olea europaea; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin. The oil is produced by pressing whole olives. It is commonly used in cooking, whether for frying or as a salad dressing. It is also used in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and soaps, and as a fuel for traditional oil lamps, and finds uses in some religions. It is associated with the Mediterranean diet popularized since the 1950s in North America for its possible health benefits. The olive is one of the three core food plants in Mediterranean cuisine, the other two being wheat and the grape.

Olive trees have been grown around the Mediterranean since the 8th millennium BC. Spain is by far the largest producer of olive oil, followed by Italy and Greece. Per capita consumption is however highest in Greece, followed by Spain, Italy, and Morocco. Consumption in North America and northern Europe is far less, but rising steadily.

The composition of olive oil varies with the cultivar, altitude, time of harvest and extraction process. It consists mainly of oleic acid (up to 83%), with smaller amounts of other fatty acids including linoleic acid (up to 21%) and palmitic acid (up to 20%). Extra-virgin olive oil is required to have no more than 0.8% free acidity and is considered to have the best flavor; it forms as much as 80% of total production in Greece and 65% in Italy, but far less in other countries.

History

Early cultivation

The olive tree is native to the Mediterranean basin; wild olives were collected by Neolithic peoples as early as the 8th millennium BC.[2] The wild olive tree originated in Asia Minor[3] or in ancient Greece.[n 1] It is not clear when and where olive trees were first domesticated: in Asia Minor, in the Levant,[2] or somewhere in the Mesopotamian Fertile Crescent.

Archeological evidence shows that olives were turned into olive oil by 6000 BC[6] and 4500 BC in present-day Israel.[7] Until 1500 BC, eastern coastal areas of the Mediterranean were most heavily cultivated. Evidence also suggests that olives were being grown in Crete as long ago as 2,500 BC. The earliest surviving olive oil amphorae date to 3500 BC (Early Minoan times), though the production of olive oil is assumed to have started before 4000 BC. Olive trees were certainly cultivated by the Late Minoan period (1500 BC) in Crete, and perhaps as early as the Early Minoan.[8] The cultivation of olive trees in Crete became particularly intense in the post-palatial period and played an important role in the island's economy, as it did across the Mediterranean.

Recent genetic studies suggest that species used by modern cultivators descend from multiple wild populations, but a detailed history of domestication is not yet forthcoming.[9]

History and trade

Olive trees and oil production in the Eastern Mediterranean can be traced to archives of the ancient city-state Ebla (2600–2240 BC), which were located on the outskirts of the Syrian city Aleppo. Here some dozen documents dated 2400 BC describe lands of the king and the queen. These belonged to a library of clay tablets perfectly preserved by having been baked in the fire that destroyed the palace. A later source is the frequent mentions of oil in the Tanakh.[10] Dynastic Egyptians before 2000 BC imported olive oil from Crete, Syria and Canaan and oil was an important item of commerce and wealth. Remains of olive oil have been found in jugs over 4,000 years old in a tomb on the island of Naxos in the Aegean Sea. Sinuhe, the Egyptian exile who lived in northern Canaan about 1960 BC, wrote of abundant olive trees.[11]

Besides food, olive oil has been used for religious rituals, medicines, as a fuel in oil lamps, soap-making, and skin care application. The Minoans used olive oil in religious ceremonies. The oil became a principal product of the Minoan civilization, where it is thought to have represented wealth. Olive oil, a multi-purpose product of Mycenaean Greece (c. 1600-1100 BC) at that time, was a chief export.[12] Olive tree growing reached Iberia and Etruscan cities well before the 8th century BC through trade with the Phoenicians and Carthage, then was spread into Southern Gaul by the Celtic tribes during the 7th century BC.

The first recorded oil extraction is known from the Hebrew Bible and took place during the Exodus from Egypt, during the 13th century BC.[13] During this time, the oil was derived through hand-squeezing the berries and stored in special containers under guard of the priests. A commercial mill for non-sacramental use of oil was in use in the tribal Confederation and later in 1000 BC, the fertile crescent, an area consisting of present-day Palestine, Lebanon, and Israel. Over 100 olive presses have been found in Tel Miqne (Ekron), where the Biblical Philistines also produced oil. These presses are estimated to have had output of between 1,000 and 3,000 tons of olive oil per season.

Many ancient presses still exist in the Eastern Mediterranean region, and some dating to the Roman period are still in use today.[14]

Olive oil was common in ancient Greek and Roman cuisine. According to Herodotus, Apollodorus, Plutarch, Pausanias, Ovid and other sources, the city of Athens obtained its name because Athenians considered olive oil essential, preferring the offering of the goddess Athena (an olive tree) over the offering of Poseidon (a spring of salt water gushing out of a cliff). The Spartans and other Greeks used oil to rub themselves while exercising in the gymnasia. From its beginnings early in the 7th century BC, the cosmetic use of olive oil quickly spread to all of the Hellenic city states, together with athletes training in the nude, and lasted close to a thousand years despite its great expense.[15][16] Olive trees were planted throughout the entire Mediterranean basin during evolution of the Roman republic and empire. According to the historian Pliny the Elder, Italy had "excellent olive oil at reasonable prices" by the 1st century AD, "the best in the Mediterranean", he maintained.

The importance and antiquity of olive oil can be seen in the fact that the English word oil derives from c. 1175, olive oil, from Anglo-Fr. and O.N.Fr. olie, from O.Fr. oile (12c., Mod.Fr. huile), from L. oleum "oil, olive oil" (cf. It. olio), from Gk. elaion "olive tree",[17][18] which may have been borrowed through trade networks from the Semitic Phoenician use of el'yon meaning "superior", probably in recognized comparison to other vegetable or animal fats available at the time. Robin Lane Fox suggests[19] that the Latin borrowing of Greek elaion for oil (Latin oleum) is itself a marker for improved Greek varieties of oil-producing olive, already present in Italy as Latin was forming, brought by Euboean traders, whose presence in Latium is signaled by remains of their characteristic pottery, from the mid-8th century.

Varieties

There are many different olive varieties or olives, each with a particular flavor, texture, and shelf life that make them more or less suitable for different applications such as direct human consumption on bread or in salads, indirect consumption in domestic cooking or catering, or industrial uses such as animal feed or engineering applications.[20]

Production and consumption

| Virgin olive oil production – 2013 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Production (tonnes) |

| | 1,110,000 |

| | 442,000 |

| | 305,900 |

| | 191,800 |

| | 187,900 |

| | 2,800,000 |

In 2013, world production of virgin olive oil was 2.8 million tonnes (table), a 20% decrease from the 2012 world production of 3.5 million tonnes.[21] Spain produced 1.1 million tonnes or 39% of world production in 2013. 75% of Spain's production derives from the region of Andalucía, particularly within Jaén province which produces 70% of olive oil in Spain.[23] The world’s largest olive oil mill, capable of processing 2,500 tons of olives per day, is in the town of Villacarrillo, Jaén.[23]

Although Italy is a net importer of olive oil, it produced 442,000 tonnes in 2013 or 16% of the world's production (table). Major Italian producers are known as "Città dell'Olio", "oil cities"; including Lucca, Florence and Siena, in Tuscany. The largest production, however, is harvested in Apulia and Calabria. Greece accounted for 11% of world production in 2013.[21]

Australia now produces a substantial amount of olive oil. Many Australian producers only make premium oils, while a number of corporate growers operate groves of a million trees or more and produce oils for the general market. Australian olive oil is exported to Asia, Europe and the United States.[24]

In North America, Italian and Spanish olive oils are the best-known, and top-quality extra-virgin olive oil from Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece are sold at high prices, often in prestige packaging. A large part of U.S. olive oil imports come from Italy, Spain, and Turkey.

The United States produces olive oil in California, Arizona, Texas, and Georgia.[25]

Regulation

The International Olive Council (IOC) is an intergovernmental organisation of states that produce olives or products derived from olives, such as olive oil. The IOC officially governs 95% of international production and holds great influence over the rest. The EU regulates the use of different protected designation of origin labels for olive oils.[26]

The United States is not a member of the IOC and is not subject to its authority, but on October 25, 2010, the U.S. Department of Agriculture adopted new voluntary olive oil grading standards that closely parallel those of the IOC, with some adjustments for the characteristics of olives grown in the U.S.[27] Additionally, U.S. Customs regulations on "country of origin" state that if a non-origin nation is shown on the label, then the real origin must be shown on the same side of the label and in comparable size letters so as not to mislead the consumer.[28][29] Yet most major U.S. brands continue to put "imported from Italy" on the front label in large letters and other origins on the back in very small print.[30] "In fact, olive oil labeled 'Italian' often comes from Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, Spain, and Greece."[31] This makes it unclear what percentage of the olive oil is really of Italian origin.

Commercial grades

All production begins by transforming the olive fruit into olive paste by crushing or pressing. This paste is then malaxed (slowly churned or mixed) to allow the microscopic oil droplets to agglomerate. The oil is then separated from the watery matter and fruit pulp with the use of a press (traditional method) or centrifugation (modern method). After extraction the remnant solid substance, called pomace, still contains a small quantity of oil.

To classify its organoleptic qualities, olive oil is judged by a panel of trained tasters in a blind taste test.

One parameter used to characterise an oil is its acidity. In this context, "acidity" is not chemical acidity in the sense of pH, but the percent (measured by weight) of free oleic acid.[32] Measured by quantitative analysis, acidity is a measure of the hydrolysis of the oil's triglycerides: as the oil degrades, more fatty acids are freed from the glycerides, increasing the level of free acidity and thereby increasing hydrolytic rancidity. Another measure of the oil's chemical degradation is the peroxide value,[33] which measures the degree to which the oil is oxidized damaged by free radicals, leading to oxidative rancidity. Phenolic acids present in olive oil also add acidic sensory properties to aroma and flavor.[34]

The grades of oil extracted from the olive fruit can be classified as:

- Virgin means the oil was produced by the use of mechanical means only, with no chemical treatment. The term virgin oil with reference to production method includes all grades of virgin olive oil, including Extra Virgin, Virgin, Ordinary Virgin and Lampante Virgin olive oil products, depending on quality (see below).

- Lampante virgin oil is olive oil extracted by virgin (mechanical) methods but not suitable for human consumption without further refining; lampante is Italian for "glaring", referring to the earlier use of such oil for burning in lamps. Lampante virgin oil can be used for industrial purposes, or refined (see below) to make it edible.[35]

- Refined Olive Oil is the olive oil obtained from any grade of virgin olive oil by refining methods which do not lead to alterations in the initial glyceridic structure. The refining process removes colour, odour and flavour from the olive oil, and leaves behind a very pure form of olive oil that is tasteless, colourless and odourless and extremely low in free fatty acids. Olive oils sold as the grades extra-virgin olive oil and virgin olive oil therefore cannot contain any refined oil.[35]

- Crude Olive Pomace Oil is the oil obtained by treating olive pomace (the leftover paste after the pressing of olives for virgin olive oils) with solvents or other physical treatments, to the exclusion of oils obtained by re-esterification processes and of any mixture with oils of other kinds. It is then further refined into Refined Olive Pomace Oil and once re-blended with virgin olive oils for taste, is then known as Olive Pomace Oil.[35]

International Olive Council

In countries that adhere to the standards of the International Olive Council (IOC),[36] as well as in Australia, and under the voluntary USDA labeling standards in the United States:

- Extra-virgin olive oil Comes from virgin oil production only, and is of higher quality: among other things, it contains no more than 0.8% free acidity, and is judged to have a superior taste, having some fruitiness and no defined sensory defects. Extra-virgin olive oil accounts for less than 10% of oil in many producing countries; the percentage is far higher in the Mediterranean countries (Greece: 80%, Italy: 65%, Spain 50%).[37]

- Virgin olive oil Comes from virgin oil production only, but is of slightly lower quality, with free acidity of up to 1.5%, and is judged to have a good taste, but may include some sensory defects.

- Refined olive oil is the olive oil obtained from virgin olive oils by refining methods that do not lead to alterations in the initial glyceridic structure. It has a free acidity, expressed as oleic acid, of not more than 0.3 grams per 100 grams (0.3%) and its other characteristics correspond to those fixed for this category in this standard. This is obtained by refining virgin olive oils with a high acidity level or organoleptic defects that are eliminated after refining. Note that no solvents have been used to extract the oil, but it has been refined with the use of charcoal and other chemical and physical filters. Oils labeled as Pure olive oil or Olive oil are primarily refined olive oil, with a small addition of virgin-production to give taste.

- Olive pomace oil is refined pomace olive oil often blended with some virgin oil. It is fit for consumption, but may not be described simply as olive oil. It has a more neutral flavor than pure or virgin olive oil, making it unfashionable among connoisseurs; however, it has the same fat composition as regular olive oil, giving it the same health benefits. It also has a high smoke point, and thus is widely used in restaurants as well as home cooking in some countries.

United States

As the United States is not a member, the IOC retail grades have no legal meaning there, but on October 25, 2010, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) established Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil, which closely parallel the IOC standards:[38][39]

- U.S. Extra Virgin Olive Oil for oil with excellent flavor and odor and free fatty acid content of not more than 0.8 g per 100 g (0.8%);

- U.S. Virgin Olive Oil for oil with reasonably good flavor and odor and free fatty acid content of not more than 2 g per 100 g (2%);

- U.S. Virgin Olive Oil Not Fit For Human Consumption Without Further Processing is a virgin (mechanically-extracted) olive oil of poor flavor and odor, equivalent to the IOC's lampante oil;

- U.S. Olive Oil is a mixture of virgin and refined oils;

- U.S. Refined Olive Oil is an oil made from refined oils with some restrictions on the processing.

These grades are voluntary. Certification is available, for a fee, from the USDA.[39]

Label wording

- Different names for olive oil indicate the degree of processing the oil has undergone as well as the quality of the oil. Extra-virgin olive oil is the highest grade available, followed by virgin olive oil. The word "virgin" indicates that the olives have been pressed to extract the oil; no heat or chemicals have been used during the extraction process, and the oil is pure and unrefined. Virgin olive oils contain the highest levels of polyphenols, antioxidants that have been linked with better health.[40]

- Olive Oil, which is sometimes denoted as being "Made from refined and virgin olive oils" is a blend of refined olive oil with a virgin grade of olive oil.[35] Pure, Classic, Light and Extra-Light are terms introduced by manufacturers in countries that are non-traditional consumers of olive oil for these products to indicate both their composition of being only 100% olive oil, and also the varying strength of taste to consumers. Contrary to a common consumer belief, they do not have fewer calories than Extra-virgin oil as implied by the names.[41]

- Cold pressed or Cold extraction means "that the oil was not heated over a certain temperature (usually 27 °C (80 °F)) during processing, thus retaining more nutrients and undergoing less degradation".[42] The difference between Cold Extraction and Cold Pressed is regulated in Europe, where the use of a centrifuge, the modern method of extraction for large quantities, must be labelled as Cold Extracted, while only a physically pressed olive oil may be labelled as Cold Pressed. In many parts of the world, such as Australia, producers using centrifugal extraction still label their products as Cold Pressed.

- First cold pressed means "that the fruit of the olive was crushed exactly one time-i.e., the first press. The cold refers to the temperature range of the fruit at the time it is crushed".[43] In Calabria (Italy) the olives are collected in October. In regions like Tuscany or Liguria, the olives collected in November and ground often at night are too cold to be processed efficiently without heating. The paste is regularly heated above the environmental temperatures, which may be as low as 10–15 °C, to extract the oil efficiently with only physical means. Olives pressed in warm regions like Southern Italy or Northern Africa may be pressed at significantly higher temperatures although not heated. While it is important that the pressing temperatures be as low as possible (generally below 25 °C) there is no international reliable definition of "cold pressed".

Furthermore, there is no "second" press of virgin oil, so the term "first press" means only that the oil was produced in a press vs. other possible methods. - PDO and PGI refers to olive oils with "exceptional properties and quality derived from their place of origin as well as from the way of their production".[44]

- The label may indicate that the oil was bottled or packed in a stated country. This does not necessarily mean that the oil was produced there. The origin of the oil may sometimes be marked elsewhere on the label; it may be a mixture of oils from more than one country.[30]

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration permitted a claim on olive oil labels stating: "Limited and not conclusive scientific evidence suggests that eating about two tablespoons (23 g) of olive oil daily may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease."[45]

Adulteration

There have been allegations, particularly in Italy and Spain, that regulation can be sometimes lax and corrupt.[46] Major shippers are claimed to routinely adulterate olive oil so that only about 40% of olive oil sold as "extra virgin" in Italy actually meets the specification.[47] In some cases, colza oil (extracted from rapeseed) with added color and flavor has been labeled and sold as olive oil.[48] This extensive fraud prompted the Italian government to mandate a new labeling law in 2007 for companies selling olive oil, under which every bottle of Italian olive oil would have to declare the farm and press on which it was produced, as well as display a precise breakdown of the oils used, for blended oils.[49] In February 2008, however, EU officials took issue with the new law, stating that under EU rules such labeling should be voluntary rather than compulsory.[50] Under EU rules, olive oil may be sold as Italian even if it only contains a small amount of Italian oil.[49]

Extra Virgin olive oil has strict requirements and is checked for "sensory defects" that include: rancid, fusty, musty, winey (vinegary) and muddy sediment. These defects can occur for different reasons. The most common are:

- Raw material (olives) infected or battered

- Inadequate harvest, with contact between the olives and soil[51]

In March 2008, 400 Italian police officers conducted "Operation Golden Oil", arresting 23 people and confiscating 85 farms after an investigation revealed a large-scale scheme to relabel oils from other Mediterranean nations as Italian.[52] In April 2008, another operation impounded seven olive oil plants and arrested 40 people in nine provinces of northern and southern Italy for adding chlorophyll to sunflower and soybean oil, and selling it as extra virgin olive oil, both in Italy and abroad; 25,000 liters of the fake oil were seized and prevented from being exported.[53]

On March 15, 2011, the prosecutor's office in Florence, Italy, working in conjunction with the forestry department, indicted two managers and an officer of Carapelli, one of the brands of the Spanish company Grupo SOS (which recently changed its name to Deoleo). The charges involved falsified documents and food fraud. Carapelli lawyer Neri Pinucci said the company was not worried about the charges and that "the case is based on an irregularity in the documents."[54]

In February 2012, an international olive oil scam was alleged by Spanish police to have taken place, in which palm, avocado, sunflower and other cheaper oils were passed off as Italian olive oil. Police said the oils were blended in an industrial biodiesel plant and adulterated in a way to hide markers that would have revealed their true nature. The oils were not toxic and posed no health risk, according to a statement by the Guardia Civil. Nineteen people were arrested following the year-long joint probe by the police and Spanish tax authorities, part of what they call Operation Lucerna.[55]

Using tiny print to state the origin of blended oil is used as a legal loophole by manufacturers of adulterated and mixed olive oil.[56]

Journalist Tom Mueller has investigated crime and adulteration in the olive oil business, publishing the article "Slippery Business" in New Yorker magazine,[57] followed by the 2011 book Extra Virginity. On 3 January 2016 Bill Whitaker presented a program on CBS News including interviews with Mueller and with Italian authorities.[58][59] It was reported that in the previous month 5,000 tons of adulterated olive oil had been sold in Italy, and that organised crime was heavily involved—the term "Agrimafia" was used. The point was made by Mueller that the profit margin on adulterated olive oil was three times that on the illegal narcotic drug cocaine. He said that over 50% of olive oil sold in Italy was adulterated, as was 75-80% of that sold in the US. Whitaker reported that 3 samples of "extra virgin olive oil" had been bought in a US supermarket and tested; two of the three samples did not meet the required standard, and one of them—with a top-selling US brand—was exceptionally poor.

Global consumption

Greece has by far the largest per capita consumption of olive oil worldwide, over 24 liters (5.3 imp gal; 6.3 U.S. gal) per person per year;[60] Spain and Italy, around 14 l; Tunisia, Portugal, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon, around 8 l. Northern Europe and North America consume far less, around 0.7 l, but the consumption of olive oil outside its home territory has been rising steadily.

Global market

The main producing and consuming countries are:

| Country | Production in tons (2010)[61] | Production % (2010) | Consumption (2012)[62] | Annual per capita consumption (kg)[63] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | 3,269,248 | 100% | 100% | 0.43 |

| Spain | 1,487,000 | 45.5% | 17% | 13.62 |

| Italy | 548,500 | 16.8% | 19% | 12.35 |

| Greece | 352,800 | 10.8% | 7% | 23.7 |

| Syria | 177,400 | 5.4% | 4% | 7 |

| Morocco | 169,900 | 5.2% | 4% | 11.1 |

| Turkey | 161,600 | 4.9% | 5% | 1.2 |

| Tunisia | 160,100 | 4.9% | 1% | 5 |

| Portugal | 66,600 | 2.0% | 2% | 7.1 |

| Algeria | 33,600 | 1.0% | 2% | 1.8 |

| Others | 111,749 | 3.5% | 39% | 1.18 |

Extraction

Olive oil is produced by grinding olives and extracting the oil by mechanical or chemical means. Green olives usually produce more bitter oil, and overripe olives can produce oil that is rancid, so for good extra virgin olive oil care is taken to make sure the olives are perfectly ripened. The process is generally as follows:

- The olives are ground into paste using large millstones (traditional method) or steel drums (modern method).

- If ground with mill stones, the olive paste generally stays under the stones for 30 to 40 minutes. A shorter grinding process may result in a more raw paste that produces less oil and has a less ripe taste, a longer process may increase oxidation of the paste and reduce the flavor. After grinding, the olive paste is spread on fiber disks, which are stacked on top of each other in a column, then placed into the press. Pressure is then applied onto the column to separate the vegetal liquid from the paste. This liquid still contains a significant amount of water. Traditionally the oil was shed from the water by gravity (oil is less dense than water). This very slow separation process has been replaced by centrifugation, which is much faster and more thorough. The centrifuges have one exit for the (heavier) watery part and one for the oil. Olive oil should not contain significant traces of vegetal water as this accelerates the process of organic degeneration by microorganisms. The separation in smaller oil mills is not always perfect, thus sometimes a small watery deposit containing organic particles can be found at the bottom of oil bottles.

- In modern steel drum mills the grinding process takes about 20 minutes. After grinding, the paste is stirred slowly for another 20 to 30 minutes in a particular container (malaxation), where the microscopic oil drops unite into bigger drops, which facilitates the mechanical extraction. The paste is then pressed by centrifugation/ the water is thereafter separated from the oil in a second centrifugation as described before.

The oil produced by only physical (mechanical) means as described above is called virgin oil. Extra virgin olive oil is virgin olive oil that satisfies specific high chemical and organoleptic criteria (low free acidity, no or very little organoleptic defects). A higher grade extra virgin olive oil is mostly dependent on favourable weather conditions; a drought during the flowering phase, for example, can result in a lower quality (virgin) oil. It is worth noting that olive trees produce well every couple of years so greater harvests occur in alternate years (the year in-between is when the tree yields less). However the quality is still dependent on the weather. - Sometimes the produced oil will be filtered to eliminate remaining solid particles that may reduce the shelf life of the product. Labels may indicate the fact that the oil has not been filtered, suggesting a different taste. Fresh unfiltered olive oil usually has a slightly cloudy appearance, and is therefore sometimes called cloudy olive oil. This form of olive oil used to be popular only among olive oil small scale producers but is now becoming "trendy", in line with consumer's demand for products that are perceived to be less processed.

The remaining paste (pomace) still contains a small quantity (about 5–10%) of oil that cannot be extracted by further pressing, but only with chemical solvents. This is done in specialised chemical plants, not in the oil mills. The resulting oil is not "virgin" but "pomace oil". The term "first press", sometimes found on bottle labels, is today meaningless, as there is no "second" press; it comes from ancient times of stone presses, when virgin oil was the one produced by battering the olives.[64]

The label term "cold-extraction" on extra virgin olive oils indicates that the olive grinding and stirring was done at a temperature of maximum 25 °C (77 °F), as treatment in higher temperatures risks decreasing the olive oils' quality (texture, taste and aroma).[64]

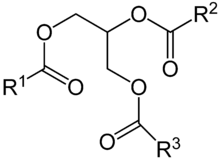

Constituents

Olive oil is composed mainly of the mixed triglyceride esters of oleic acid and palmitic acid and of other fatty acids, along with traces of squalene (up to 0.7%) and sterols (about 0.2% phytosterol and tocosterols). The composition varies by cultivar, region, altitude, time of harvest, and extraction process.

| Fatty acid | Percentage | ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic acid | 55 to 83% | [65][66] |

| Linoleic acid | 3.5 to 21% | [65][66] |

| Palmitic acid | 7.5 to 20% | [65] |

| Stearic acid | 0.5 to 5% | [65] |

| α-Linolenic acid | 0 to 1.5% | [65] |

Phenolic composition

Olive oil contains phenolics, such as esters of tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, oleocanthal and oleuropein,[34][67] having acidic properties that give extra-virgin unprocessed olive oil its aroma and bitter, pungent taste.[68] Olive oil is a source of at least 30 phenolic compounds, among which is elenolic acid, a marker for maturation of olives.[34][69] Oleuropein, together with other closely related compounds such as 10-hydroxyoleuropein, ligstroside and 10-hydroxyligstroside, are tyrosol esters of elenolic acid.

Other phenolic constituents include flavonoids, lignans and pinoresinol.[70][71]

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 3,699 kJ (884 kcal) |

|

0 g | |

|

100 g | |

| Saturated | 14 g |

| Monounsaturated | 73 g |

| Polyunsaturated |

11 g 0.8 g 9.8 g |

|

0 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin E |

(93%) 14 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(57%) 60 μg |

| Minerals | |

| Iron |

(4%) 0.56 mg |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

One tablespoon of olive oil (13.5 g) contains the following nutritional information according to the USDA:[72]

- Calories: 119

- Fat: 13.50 g (21% of the Daily Value, DV)

- Saturated fat: 2 g (9% of DV)

- Carbohydrates: 0

- Fibers: 0

- Protein: 0

- Vitamin E: 1.9 mg (10% of DV)

- Vitamin K: 8.1 µg (10% of DV)

Popular uses and research

Skin

Olive oil has a long history of being used as a home remedy for skincare. Egyptians used it alongside beeswax as a cleanser, moisturizer, and antibacterial agent since pharaonic times.[73] In ancient Greece, the substance was used during massage, to prevent sports injuries, relieve muscle fatigue, and eliminate lactic acid buildup.[74] In 2000, Japan was the top importer of olive oil in Asia (13,000 tons annually) because consumers there believe both the ingestion and topical application of olive oil to be good for skin and health.[75]

There has been relatively little scientific work done on the effect of olive oil on acne and other skin conditions. However, one study noted that squalene, which is in olive oil,[76] may contribute to relief of seborrheic dermatitis, acne, psoriasis or atopic dermatitis.[77]

Olive oil is popular for use in massaging infants and toddlers, but scientific evidence of its efficacy is mixed. One analysis of olive oil versus mineral oil found that, when used for infant massage, olive oil can be considered a safe alternative to sunflower, grapeseed and fractionated coconut oils. This stands true particularly when it is mixed with a lighter oil like sunflower, which "would have the further effect of reducing the already low levels of free fatty acids present in olive oil".[78] Another trial stated that olive oil lowered the risk of dermatitis for infants in all gestational stages when compared with emollient cream.[79] However, yet another study on adults found that topical treatment with olive oil "significantly damages the skin barrier" when compared to sunflower oil, and that it may make existing atopic dermatitis worse. The researchers concluded that due to the negative outcome in adults, they do not recommend the use of olive oil for the treatment of dry skin and infant massage.[80]

Applying olive oil to the skin does not help prevent or reduce stretch marks.[81]

Potential health effects: fat and polyphenol composition

Olive oil consumption is thought to affect cardiovascular health.[82] It has been suggested that long-term consumption of small quantities of the polyphenol, oleocanthal, from olive oil may be responsible in part for the low incidence of heart disease associated with a Mediterranean diet.[83] Epidemiological studies indicate that a higher proportion of monounsaturated fats in the diet may be linked with a reduction in the risk of coronary heart disease.[84] There is preliminary evidence that regular consumption of olive oil may lower risk of all-cause mortality and several chronic diseases.[82][85]

In a comprehensive scientific review by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2011, health claims on olive oil were approved for protection by its polyphenols against oxidation of blood lipids,[86] and for the contribution to the maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol levels by replacing saturated fats in the diet with oleic acid[87] (Commission Regulation (EU) 432/2012 of 16 May 2012).[88] A cause-and-effect relationship has not been adequately established for consumption of olive oil and maintaining normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides, normal blood HDL-cholesterol concentrations, and normal blood glucose concentrations.[89]

A 2011 meta-analysis concluded that olive oil consumption may play a protective role against the development of any type of cancer, but could not clarify whether the beneficial effect is due to olive oil monounsaturated fatty acid content or its antioxidant components.[90]

A 2014 meta-analysis concluded that an elevated consumption of olive oil is associated with reduced risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events and stroke, while monounsaturated fatty acids of mixed animal and plant origin showed no significant effects.[91]

In the United States, producers of olive oil may place the following restricted health claim on product labels:

- Limited and not conclusive scientific evidence suggests that eating about 2 tbsp. (23 g) of olive oil daily may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease due to the monounsaturated fat in olive oil. To achieve this possible benefit, olive oil is to replace a similar amount of saturated fat and not increase the total number of calories you eat in a day.[92]

This decision was announced November 1, 2004 after application to the FDA by producers.[93] Similar labels are permitted for foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids such as walnuts and hemp seed.[94]

Uses

Culinary use

Olive oil is the main cooking oil in countries surrounding the Mediterranean, and it forms one of the three staple food plants of Mediterranean cuisine, the other two being wheat (as in pasta, bread, and couscous) and the grape, used as a dessert fruit and for wine.[95]

Extra virgin olive oil is mostly used as a salad dressing and as an ingredient in salad dressings. It is also used with foods to be eaten cold. If uncompromised by heat, the flavor is stronger. It also can be used for sautéing.

The higher the temperature to which the olive oil is heated, the higher the risk of compromising its taste. When extra virgin olive oil is heated above 210–216 °C (410–421 °F), depending on its free fatty acid content, the unrefined particles within the oil are burned. This leads to deteriorated taste. Also, the pronounced taste of extra virgin olive oil is not a taste most people like to associate with their deep fried foods. Refined olive oils are perfectly suited for deep frying foods and should be replaced after several uses.

Choosing a cold-pressed olive oil can be similar to selecting a wine. The flavor of these oils varies considerably and a particular oil may be more suited for a particular dish.

An important issue often not realized in countries that do not produce olive oil is that the freshness makes a big difference. A very fresh oil, as available in an oil producing region, tastes noticeably different from the older oils available elsewhere. In time, oils deteriorate and become stale. One-year-old oil may be still pleasant to the taste, but it is less fragrant than fresh oil. After the first year, olive oil should be used for cooking, not for foods to be eaten cold, like salads.

The taste of the olive oil is influenced by the varietals used to produce the oil and by the moment when the olives are harvested and ground (less ripe olives give more bitter and spicy flavors – riper olives give a sweeter sensation in the oil).

Religious use

Olive oil also has religious symbolism for healing and strength and to consecration—setting a person or place apart for special work. This may be related to its ancient use as a medicinal agent and for cleansing athletes by slathering them in oil then scraping them.

Judaism

In Jewish observance, olive oil is the only fuel allowed to be used in the seven-branched Menorah in the Mishkan service during the Exodus of the tribes of Israel from Egypt, and later in the permanent Temple in Jerusalem. It was obtained by using only the first drop from a squeezed olive and was consecrated for use only in the Temple by the priests and stored in special containers. A menorah similar to the Menorah used in the Mishkan is now used during the holiday of Hanukkah that celebrates the miracle of the last of such containers being found during the re-dedication of the Temple (163 BC), when its contents lasted for far longer than they were expected to, allowing more time for more oil to be made. Although candles can be used to light the hanukkiah, oil containers are preferred, to imitate the original Menorah. Another use of oil in Jewish religion is for anointing the kings of the Kingdom of Israel, originating from King David. Tzidkiyahu was the last anointed King of Israel.

Christianity

The Roman Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican churches use olive oil for the Oil of Catechumens (used to bless and strengthen those preparing for Baptism) and Oil of the Sick (used to confer the Sacrament of Anointing of the Sick or Unction). Olive oil mixed with a perfuming agent such as balsam is consecrated by bishops as Sacred Chrism, which is used to confer the sacrament of Confirmation (as a symbol of the strengthening of the Holy Spirit), in the rites of Baptism and the ordination of priests and bishops, in the consecration of altars and churches, and, traditionally, in the anointing of monarchs at their coronation. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Latter-day Saints) and a number of other religions use olive oil when they need to consecrate an oil for anointings.

Eastern Orthodox Christians still use oil lamps in their churches, home prayer corners and in the cemeteries. A vigil lamp consists of a votive glass containing a half-inch of water and filled the rest with olive oil. The glass has a metal holder that hangs from a bracket on the wall or sits on a table. A cork float with a lit wick floats on the oil. To douse the flame, the float is carefully pressed down into the oil. Makeshift oil lamps can easily be made by soaking a ball of cotton in olive oil and forming it into a peak. The peak is lit and then burns until all the oil is consumed, whereupon the rest of the cotton burns out. Olive oil is a usual offering to churches and cemeteries.

In the Orthodox Church, olive oil is a product not consumed during lent or penance while Orthodox monks use it sparingly in their diet. Exceptions are in feast days and Sundays.

Islam

In Islam, olive oil is mentioned in the Quranic verse:

"God is the Light of the heavens and the earth. The parable of His Light is as (if there were) a niche and within it a lamp: the lamp is in a glass, the glass as it were a brilliant star, lit from a blessed tree, an olive, neither of the east nor of the west, whose oil would almost glow forth (of itself) though no fire touched it. Light upon Light! God guides to His Light whom He wills. And God sets forth parables for mankind, and God is All-Knower of everything." (سورة النور, An-Noor (The Light), Chapter #24, Verse #35)

Other

Olive oil is also a natural and safe lubricant, and can be used to lubricate kitchen machinery (grinders, blenders, cookware, etc.) It can also be used for illumination (oil lamps) or as the base for soaps and detergents.[96] Some cosmetics also use olive oil as their base.[97]

- Olive oil may be used in soap making, as lamp oil, a lubricant, or as a substitute for machine oil.[98][99][100]

- Olive oil has also been used as both solvent and ligand in the synthesis of cadmium selenide quantum dots.[101]

- In one study, monounsaturated fats such as from olive oil benefited mood, decreased anger, and increased physical activity.[102]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Greek word for olive oil or for oil in general, ἔλαιον (elaion),[4] is first attested in the Mycenaean Greek forms 𐀁𐀨𐀺, e-ra-wo and 𐀁𐁉𐀺, e-rai-wo, written in the Linear B syllabic script.[5] In Linear B there was also 𐂕, an ideogram standing for olive oil or oil in general.

References

- ↑ "United States Department of Agriculture: "Grading Manual for Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil"". Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- 1 2 Davidson, s.v. Olives

- ↑ "International Olive Council". Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ↑ ἔλαιον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ "The Linear B word e-ra-wo". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages. "e-ra3-wo". Raymoure, K.A. "e-ra-wo". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean.

- ↑ Ruth Schuster (December 17, 2014). "8,000-year old olive oil found in Galilee, earliest known in world", Haaretz. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Ehud Galili et al., "Evidence for Earliest Olive-Oil Production in Submerged Settlements off the Carmel Coast, Israel", Journal of Archaeological Science 24:1141–1150 (1997); Pagnol, p. 19, says the 6th millennium in Jericho, but cites no source.

- ↑ F. R. Riley, "Olive Oil Production on Bronze Age Crete: Nutritional properties, Processing methods, and Storage life of Minoan olive oil", Oxford Journal of Archaeology 21:1:63–75 (2002)

- ↑ Guillaume Besnarda, André Bervillé, "Multiple origins for Mediterranean olive (Olea europaea L. ssp. europaea) based upon mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences—Series III—Sciences de la Vie 323:2:173–181 (February 2000); Catherine Breton, Michel Tersac and André Bervillé, "Genetic diversity and gene flow between the wild olive (oleaster, Olea europaea L.) and the olive: several Plio-Pleistocene refuge zones in the Mediterranean basin suggested by simple sequence repeats analysis", Journal of Biogeography 33:11:1916 (November 2006)

- ↑ Nathaniel R. Brown (June 11, 2011). "By the Rivers of Babylon: The Near Eastern Background and Influence on the Power Structures Ancient Israel and Judah" (PDF). history.ucsc.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ↑ Gardiner, Alan H. (1916). Notes on the Story of Sinuhe. Paris: Librairie Honoré Champion.

- ↑ Castleden, Rodney (2005). The Mycenaeans. London and New York: Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 0-415-36336-5.

Huge quantities of olive oil were produced and it must have been a major source of wealth. The simple fact that southern Greece is far more suitable climatically for olive production may explain why the Mycenaean civilization made far greater advances in the south than in the north. The oil had a variety of uses, in cooking, as a dressing, as soap, as lamp oil, and as a base for manufacturing unguents.

- ↑ Andrew C. Skinner (2000). "Autumn, Olives, and the Atonement". rsc.byu.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ↑ J.M. Blásquez (1992). "The Latest Work on the Export of Baetican Olive Oil to Rome and the Army" (PDF). ceipac.ub.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ↑ Thomas F. Scanlon, "The Dispersion of Pederasty and the Athletic Revolution in sixth-century BC Greece", in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, ed. B. C. Verstraete and V. Provençal, Harrington Park Press, 2005

- ↑ Nigel M. Kennell, "Most Necessary for the Bodies of Men: Olive Oil and its By-products in the Later Greek Gymnasium" in Mark Joyal (ed.), In Altum: Seventy-Five Years of Classical Studies in Newfoundland, 2001; popis pp. 119–33

- ↑ "Olive – Define Olive at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ "Oil – Define Oil at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ Fox, Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer, 2008:127.

- ↑ Nicole Sturzenberger (2007). "Olive Processing Waste Management: Summary" (PDF). oliveoil.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Olive oil virgin, crops processed, production data for 2013". Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division. 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ↑ Oteros J, et al. (2014). "Better prediction of Mediterranean olive production using pollen-based models". Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 34 (3): 685–694. doi:10.1007/s13593-013-0198-x.

- 1 2 Lucy Vivante (2011). "Gruppo Pieralisi Powers World's Largest Olive Oil Mill in Jaén". Olive Oil Times. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Sarah Schwager (August 31, 2010). "Australia Charts Five-Year Course for Olive Oil Industry". Olive Oil Times.

- ↑ "The Best Olive Oils Made in the U.S.". Article. Wall Street Journal. October 18, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Olive Oil Times". Olive Oil Times. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ "New U.S. Olive Oil Standards in Effect Today". Olive Oil Times. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ Durant, John (September 5, 2000). "U.S. Customs Department, Director Commercial Rulings Division – Country of origin marking of imported olive oil; 19 CFR 134.46; "imported by" language".

- ↑ "Reference to HQ 560944 ruling of the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) on April 27, 1999 blending of Spanish olive oil with Italian olive oil in Italy does not result in a substantial transformation of the Spanish product". United States International Trade Commission Rulings. February 28, 2006.

- 1 2 McGee, Dennis. "Deceptive Olive Oil Labels on Major Brands (includes photos)". Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ↑ Raymond Francis (1998). "The Olive Oil Scandal" (PDF). beyondhealth.com.

- ↑ Grossi, M.; Di Lecce, G.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Riccò, B. (2014). "Fast and accurate determination of olive oil acidity by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy". IEEE Sensors Journal. 14 (9): 2947–2954. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2014.2321323.

- ↑ Grossi, Marco; Di Lecce, Giuseppe; Arru, Marco; Gallina Toschi, Tullia; Riccò, Bruno (2015). "An opto-electronic system for in-situ determination of peroxide value and total phenol content in olive oil". Journal of Food Engineering. 146: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.08.015.

- 1 2 3 Bendini A, Cerretani L, Carrasco-Pancorbo A, Gómez-Caravaca AM, Segura-Carretero A, Fernández-Gutiérrez A, Lercker G (2007). "Phenolic molecules in virgin olive oils: a survey of their sensory properties, health effects, antioxidant activity and analytical methods. An overview of the last decade". Molecules. 12 (8): 1679–719. doi:10.3390/12081679. PMID 17960082.

- 1 2 3 4 "The 101 of olive oil designations and definitions.". Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Designations and definitions of olive oils". International Olive Council. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Olive Oil Production". Prosodol. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ "United States Standard for Grades of Olive Oil". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- 1 2 "United States Standard for Grades of Olive Oil" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Bone density scan ... Olive oil ... Bursitis". Women's Health Advisor. 14 (7): 8. 2010.

- ↑ Deborah Bogle/Tom Mueller "Losing our Virginity" The Advertiser May 12, 2012 p. 11–14

- ↑ "Health Diaries.". Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ "California Olive Ranch.". Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.agrocert.gr/pages/Content.asp?cntID=26&catID=15

- ↑ Drummond, Linda, Sunday Telegraph (Australia), October 17, 2010 Sunday, Features; p. 10.

- ↑ "Report SCUSI, LEI E' VERGINE?". rai.it.

- ↑ Tom Mueller (August 13, 2007). "Slippery Business". The New Yorker.

- ↑ "EUbusiness.com".

- 1 2 Moore, Malcolm (May 7, 2007). "Murky Italian olive oil to be pored over". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Eubusiness.com".

- ↑ "草刈りは定期的に". Novaoliva.com. February 21, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ↑ Moore, Malcolm (March 5, 2008). "Italian police crack down on olive oil fraud". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ Pisa, Nick (April 22, 2008). "Forty arrested in new 'fake' olive oil scam". The Scotsman. Edinburgh.

- ↑ "Investigations Into Deodorized Olive Oils". Olive Oil Times. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Spanish Police Say Palm, Avocado, Sunflower Was Passed Off as Olive Oil". Olive Oil Times.

- ↑ Nadeau, Barbie Latza (2015-11-14). "Has the Italian Mafia Sold You Fake Extra Virgin Olive Oil?". The Daily Beast.

- ↑ Mueller, Tom (August 13, 2007). "Slippery Business". The New Yorker. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ Whitaker, Bill. (3 January 2016). "Agromafia". 60 Minutes. Retrieved 3 January 2016. 10-minute video

- ↑ "Mafia Control of Olive Oil the Topic of '60 Minutes' Report". Olive Oil Times. 3 January 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.. Summary of CBS video

- ↑ "Olive Oil Consumption". About Olive Oil. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ http://faostat.fao.org/site/636/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=636#ancor

- ↑ Ammar Assabah. "Olive Oil Market Trends" (PDF). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

- ↑ "California and World Olive Oil Statistics" (PDF). UC Davis. (Current link, Archive link to old address)

- 1 2 Williamson, Daniel (September 9, 2010). "Olive Pomace Oil: Not What You Might Think". Olive Oil Times.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Olive Oil : Chemical Characteristics".

- 1 2 Beltran; et al. (2004). "Influence of Harvest Date and Crop Yield on the Fatty Acid Composition of Virgin Olive Oils from Cv. Picual" (PDF).

- ↑ "The phenolic compounds of olive oil: structure, biological activity and beneficial effects on human health". Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ Genovese A, Caporaso N, Villani V, Paduano A, Sacchi R (2015). "Olive oil phenolic compounds affect the release of aroma compounds". Food Chem. 181: 284–94. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.097. PMID 25794752.

- ↑ Lozano-Sánchez J, Castro-Puyana M, Mendiola JA, Segura-Carretero A, Cifuentes A, Ibáñez E (2014). "Recovering bioactive compounds from olive oil filter cake by advanced extraction techniques". Int J Mol Sci. 15 (9): 16270–83. doi:10.3390/ijms150916270. PMC 4200768

. PMID 25226536.

. PMID 25226536. - ↑ RW Owen, A Giacosa, WE Hull, R Haubner, B Spiegelhalder, H Bartsch (2000). "The antioxidant/anticancer potential of phenolic compounds isolated from olive oil". European Journal of Cancer. 36 (10): 1235–1247. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00103-9. PMID 10882862.

- ↑ RW Owen, W Mier, A Giacosa, WE Hull, B Spiegelhalder, H Bartsch (2000). "Identification of lignans as major components in the phenolic fraction of olive oil" (PDF). Clinical Chemistry. 46 (7): 976–988.

- ↑ "NDL/FNIC Food Composition Database Home Page". Nal.usda.gov. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ↑ Grossman, A. J. (September 27, 2007). "Behind a Mysterious Balm, a Self-Made Pharaoh". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Nomikos NN, Nomikos GN, Kores DS (2010). "The use of deep friction massage with olive oil as a means of prevention and treatment of sports injuries in ancient times". Arch Med Sci. 6 (5): 642–5. doi:10.5114/aoms.2010.17074. PMC 3298328

. PMID 22419918.

. PMID 22419918. - ↑ Shoji, K. (February 26, 2013). "The Japanese woman's perpetual quest for perfect skin". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Ghanbari, R; Anwar, F; Alkharfy, K. M.; Gilani, A. H.; Saari, N (2012). "Valuable Nutrients and Functional Bioactives in Different Parts of Olive (Olea europaea L.)-A Review". International journal of molecular sciences. 13 (3): 3291–340. doi:10.3390/ijms13033291. PMC 3317714

. PMID 22489153.

. PMID 22489153. - ↑ Wołosik, K.; Knaś, M.; Zalewska, A.; Niczyporuk, M.; Przystupa, A. W. (2013). "The importance and perspective of plant-based squalene in cosmetology". Journal of cosmetic science. 64 (1): 59–66. PMID 23449131.

- ↑ Carpenter, P.; Richards, K. (2011). "Olive versus mineral oil". Community practitioner : the journal of the Community Practitioners' & Health Visitors' Association. 84 (2): 40–42. PMID 21388045.

- ↑ Kiechl-Kohlendorfer, U.; Berger, C.; Inzinger, R. (2008). "The Effect of Daily Treatment with an Olive Oil/Lanolin Emollient on Skin Integrity in Preterm Infants: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Pediatric Dermatology. 25 (2): 174–178. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00627.x. PMID 18429773.

- ↑ Danby, S. G.; Alenezi, T.; Sultan, A.; Lavender, T.; Chittock, J.; Brown, K.; Cork, M. J. (2013). "Effect of Olive and Sunflower Seed Oil on the Adult Skin Barrier: Implications for Neonatal Skin Care". Pediatric Dermatology. 30 (1): 42–50. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01865.x. PMID 22995032.

- ↑ Moore J, Kelsberg G, Safranek S (December 2012). "Clinical Inquiry: Do any topical agents help prevent or reduce stretch marks?". J Fam Pract. 61 (12): 757–8. PMID 23313995.

- 1 2 Schwingshackl, L; Hoffmann, G (2014). "Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and health status: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies". Lipids in Health and Disease. 13: 154. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-13-154. PMC 4198773

. PMID 25274026.

. PMID 25274026. - ↑ Lucas, L.; Russell, A.; Keast, R. (2011). "Molecular mechanisms of inflammation. Anti-inflammatory benefits of virgin olive oil and the phenolic compound oleocanthal". Current pharmaceutical design. 17 (8): 754–768. doi:10.2174/138161211795428911. PMID 21443487.

- ↑ Keys A, Menotti A, Karvonen MJ, et al. (December 1986). "The diet and 15-year death rate in the seven countries study". Am. J. Epidemiol. 124 (6): 903–15. PMID 3776973.

- ↑ Buckland G, González CA (Apr 2015). "The role of olive oil in disease prevention: a focus on the recent epidemiological evidence from cohort studies and dietary intervention trials" (PDF). Br J Nutr (Review). 113 Suppl 2: S94–101. doi:10.1017/S0007114514003936.

- ↑ European Food Safety Authority (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to polyphenols in olive". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2033.

- ↑ European Food Safety Authority (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to oleic acid intended to replace saturated fatty acids (SFAs) in foods or diets". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2043.

- ↑ "COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) No 432/2012 of 16 May 2012 establishing a list of permitted health claims made on foods, other than those referring to the reduction of disease risk and to children's development and health. Text with EEA relevance". Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ↑ Scientific Committee/Scientific Panel of the European Food Safety Authority (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to olive oil and maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 1316, 1332), maintenance of normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides (ID 1316, 1332), maintenance of normal blood HDL cholesterol concentrations (ID 1316, 1332) and maintenance of normal blood glucose concentrations (ID 4244) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006" (PDF). EFSA Journal. European Commission. 9 (4): 2044 [19 pp]. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2044. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Psaltopoulou T, Kosti RI, Haidopoulos D, Dimopoulos M, Panagiotakos DB (2011). "Olive oil intake is inversely related to cancer prevalence: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of 13,800 patients and 23,340 controls in 19 observational studies.". Lipids Health Dis. 10: 127. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-10-127. PMC 3199852

. PMID 21801436.

. PMID 21801436. - ↑ Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G (Oct 1, 2014). "Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies". Lipids Health Dis (Review). 13: 154. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-13-154. PMC 4198773

. PMID 25274026.

. PMID 25274026. - ↑ "FDA Allows Qualified Health Claim to Decrease Risk of Coronary Heart Disease". US Food and Drug Administration. November 2004. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ Brackett, RE (November 2004). "Letter Responding to Health Claim Petition dated August 28, 2003: Monounsaturated Fatty Acids from Olive Oil and Coronary Heart Disease (Docket No 2003Q-0559)". US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Marian Burros (November 2, 2004). "Olive Oil Makers Win Approval to Make Health Claim on Label". The New York Times. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ↑ Essid, Mohamed Yassine (2012). Chapter 2. History of Mediterranean Food. MediTerra: The Mediterranean Diet for Sustainable Regional Development. Presses de Sciences Po. pp. 51–69. ISBN 9782724612486.

- ↑ "Soap Making from Scratch Workshop". Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "The olive essence". Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Castile Olive Oil Soap, Spain, 2000 BCE". smith.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Synthesis of Soap from Olive Oil" (PDF). webpages.uidaho.edu. 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ↑ "California olive oil is worth the splurge". ucanr.edu (Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources). Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ↑ Sameer Sapra; Andrey L. Rogach; Jochen Feldmann (2006). "Phosphine-free synthesis of monodisperse CdSe nanocrystals in olive oil". Journal of Materials Chemistry. 16 (33): 3391–3395. doi:10.1039/B607022A.

- ↑ Kien, CL; et al. (2013). "Substituting dietary monounsaturated fat for saturated fat is associated with increased daily physical activity and resting energy expenditure and with changes in mood". Am J Clin Nutr. 97 (4): 689–97. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.051730. PMID 23446891.

Further reading

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olive oil. |

- Caruso, Tiziano / Magnano di San Lio, Eugenio (eds.). La Sicilia dell'olio, Giuseppe Maimone Editore, Catania, 2008, ISBN 978-88-7751-281-9

- Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food, Oxford, 1999. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

- Mueller, Tom. Extra Virginity – The Sublime and Scandalous World of Olive Oil, Atlantic Books, London, 2012. ISBN 978-1-84887-004-8.

- Pagnol, Jean. L'Olivier, Aubanel, 1975. ISBN 2-7006-0064-9.

- Palumbo, Mary; Linda J. Harris (December 2011) "Microbiological Food Safety of Olive Oil: A Review of the Literature" (PDF), University of California, Davis

- Preedy, V.R. / Watson, R.R. (eds.). Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention, Academic Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-12-374420-3.

- Rosenblum, Mort. Olives: The Life and Lore of a Noble Fruit, North Point Press, 1996. ISBN 0-86547-503-2.

- CODEX STAN 33-1981 Standard for Olive Oils and Olive Pomace Oils

.jpg)