Mycenaean Greek

| Mycenaean Greek | |

|---|---|

| Region | southern Balkans/Crete |

| Era | 16th–12th century BC |

|

Indo-European

| |

| Linear B | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

gmy |

Linguist list |

gmy |

| Glottolog |

myce1241[1] |

|

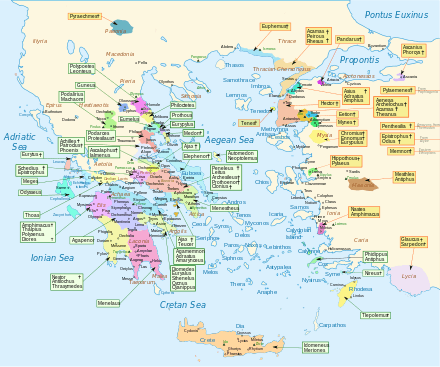

Map of Greece as described in Homer's Iliad. The geographical data is believed to refer primarily to Bronze Age Greece, when Mycenaean Greek would have been spoken and so can be used as an estimator of the range. | |

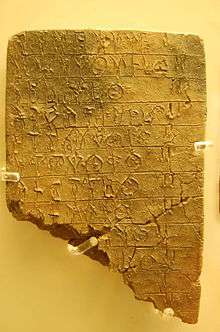

Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient attested form of the Greek language, on the Greek mainland, Crete and Cyprus in Mycenaean Greece (16th to 12th centuries BCE), before the hypothesised Dorian invasion, often cited as the terminus post quem for the coming of the Greek language to Greece. The language is preserved in inscriptions in Linear B, a script first attested on Crete before the 14th century. Most inscriptions are on clay tablets found in Knossos, in central Crete, as well as in Pylos, in the southwest of the Peloponnese. Other tablets have been found at Mycenae itself, Tiryns and Thebes and at Chania, in Western Crete.[2] The language is named after Mycenae, one of the major centres of Mycenaean Greece.

The tablets long remained undeciphered, and many languages were suggested for them, until Michael Ventris deciphered the script in 1952.

The texts on the tablets are mostly lists and inventories. No prose narrative survives, much less myth or poetry. Still, much may be glimpsed from these records about the people who produced them and about Mycenaean Greece, the period before the so-called Greek Dark Ages.

Orthography

The Mycenaean language is preserved in Linear B writing, which consists of about 200 syllabic signs and logograms. Since Linear B was derived from Linear A, the script of an undeciphered Minoan language probably unrelated to Greek, it does not reflect fully the phonetics of Mycenaean. In essence, a limited number of syllabic signs must represent a much greater number of produced syllables, better represented phonetically by the letters of an alphabet.

Orthographic simplifications therefore had to be made:[3]

- There is no disambiguation for the Greek categories of voice and aspiration.except dentals d, t: 𐀁𐀒, e-ko may be either egō ("I") or ekhō ("I have").

- Any m or n, before a consonant, and any syllable-final l, m, n, r, s are omitted. 𐀞𐀲, pa-ta is panta ("all"); 𐀏𐀒, ka-ko is khalkos ("copper").

- Consonant clusters must be dissolved orthographically, creating apparent vowels: 𐀡𐀵𐀪𐀚, po-to-ri-ne is ptolin (classical polin, "city" ACC).

- R and l are not disambiguated: 𐀣𐀯𐀩𐀄, qa-si-re-u is gʷasileus (classical basileus, "king").

- Initial aspiration is not indicated: 𐀀𐀛𐀊, a-ni-ja is hāniai ("reins").

- Length of vowels is not marked.

- The consonant usually transcribed z probably represents *dy, initial *y, *ky, *gy.[4]

- q- is a labio-velar kʷ or gʷ and in some names ghʷ:[4] 𐀣𐀄𐀒𐀫, qo-u-ko-ro is gʷoukoloi (classical boukoloi, "cowherds").

- Initial s before a consonant is not written: 𐀲𐀵𐀗, ta-to-mo is stathmos ("station, outpost").

- Double consonants are not represented: 𐀒𐀜𐀰, ko-no-so is Knōsos (classical Knossos).

In addition to the spelling rules, signs are not polyphonic (more than one sound), but sometimes are homophonic (a sound can be represented by more than one sign), which are not "true homophones" but are "overlapping values."[5] Long words may omit a middle or final sign.

Phonology

| Type | Bilabial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | lab. | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | ts* | k | kʷ | |

| voiced | b | d | dz* | ɡ | ɡʷ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | kʷʰ | |||

| Fricative | s | h | |||||

| Approximant | j | w | |||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

| Lateral | l | ||||||

Mycenaean preserves some archaic Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Greek features not present in later Ancient Greek.

One archaic feature is the set of labiovelar consonants [ɡʷ, kʷ, kʷʰ], written ⟨q⟩, which split into /b, p, pʰ/, /d, t, tʰ/, or /g k kʰ/ in Ancient Greek, depending on the context and the dialect.

Another set is the semivowels /j w/ and the glottal fricative /h/ between vowels. All were lost in standard Attic Greek, but /w/ was preserved in some Greek dialects and written as digamma ⟨ϝ⟩ or beta ⟨β⟩.

It is unclear how the sound transcribed as ⟨z⟩ was pronounced. It may have been a voiced or voiceless affricate /dz/ or /ts/, marked with asterisks in the table above. It derives from [kʲ], [ɡʲ], [dʲ] and some initial [j] and was written as ζ in the Greek alphabet. In Attic, it was pronounced [zd] in many cases, but it is [z] in Modern Greek.

There were at least five vowels /a e i o u/, which could be both short and long.

As noted above, the syllabic Linear B script used to record Mycenaean is extremely defective and distinguishes only the semivowels ⟨j w⟩; the sonorants ⟨m n r⟩; the sibilant ⟨s⟩; the stops ⟨p t d k q z⟩; and (marginally) ⟨h⟩. Voiced, voiceless and aspirate occlusives are all written with the same symbols except that ⟨d⟩ stands for /d/ and ⟨t⟩ for both /t/ and /tʰ/). Both /r/ and /l/ are written ⟨r⟩; /h/ is unwritten unless followed by /a/.

The length of vowels and consonants is not notated. In most circumstances, the script is unable to notate a consonant not followed by a vowel. Either an extra vowel is inserted (often echoing the quality of the following vowel), or the consonant is omitted. (See above for more details.)

Thus, determining the actual pronunciation of written words is often difficult, and using of a combination of the PIE etymology of a word, its form in later Greek and variations in spelling is necessary. Even so, for some words the pronunciation is not known exactly especially when the meaning is unclear from context, or the word has no descendants in the later dialects.

Morphology

Unlike later varieties of Greek, Mycenaean Greek probably had seven grammatical cases, nominative, genitive, accusative, dative, instrumental, locative and vocative. Instrumental and locative had fallen out of use by Classical Greek and in Modern Greek, only nominative, accusative, genitive and vocative remain.[6]

Also unlike later varieties of Ancient Greek, the verbal augment is almost entirely absent from Mycenaean Greek with only one known exception, 𐀀𐀟𐀈𐀐, a-pe-do-ke (PY Fr 1184), but even that appears elsewhere without the augment, as 𐀀𐀢𐀈𐀐, a-pu-do-ke (KN Od 681). Omission of the augment occurs in Homer in which it is sometimes included and sometimes not.[7]

Greek features

Mycenaean has already undergone the following sound changes peculiar to the Greek language and therefore is considered to be Greek.[8]

Phonological changes

- Initial and intervocalic *s has become /h/.

- Voiced aspirates have been devoiced.

- Syllabic liquids have become /ar,al/ or /or,ol/; syllabic nasals have become /a/ or /o/.

- *kj and *tj have become /s/ before a vowel.

- Initial *j has become /h/ or replaced by ζ (exact value unknown, possibly [dz]).

- *gj and *dj have become ζ.

Morphological changes

- The use of -eus to produce agent nouns

- The third person singular ending -ei

- The infinitive ending -ein (contracted from -e-en)

Lexical items

- Uniquely Greek words:

- Greek forms of words known in other languages:

Corpus

The corpus of Mycenaean-era Greek writing consists of some 6,000 tablets and potsherds in Linear B, from LMII to LHIIIB. No Linear B monuments or non-Linear B transliterations have yet been found.

If it is genuine, the Kafkania pebble, dated to the 17th century BC, would be the oldest known Mycenean inscription, and hence the earliest preserved testimony of the Greek language, but it is likely a hoax.[9]

Survival

While the use of Mycenaean Greek may have ceased with the fall of the Mycenaean civilization, some traces of it are found in the later Greek dialects. In particular, Arcadocypriot Greek is believed to be rather close to Mycenaean Greek. Arcadocypriot was an ancient Greek dialect spoken in Arcadia (central Peloponnese), and in Cyprus.

Ancient Pamphylian also shows some similarity to Arcadocypriot and to Mycenaean Greek.

Variation within corpus

While the Mycenaean dialect is relatively uniform at all the centres where it is found, there are also a few traces of dialectal variants:

- i for e in the dative of consonant stems

- a instead of o as the reflex of ṇ (e.g. pe-ma instead of pe-mo < *spermn)

- the e/i variation in e.g. te-mi-ti-ja/ti-mi-ti-ja

Based on such variations, Ernst Risch (1966) postulated the existence of some dialects within Linear B.[10] The "Normal Mycenaean" would have been the standardized language of the tablets, and the "Special Mycenaean" represented some local vernacular dialect (or dialects) of the particular scribes producing the tablets.[11]

Thus, "a particular scribe, distinguished by his handwriting, reverted to the dialect of his everyday speech"[11] and used the variant forms, such as the examples above.

It follows that after the collapse of Mycenaean Greece, while the standardized Mycenaean language was no longer used, the particular local dialects reflecting local vernacular speech would have continued, eventually producing the various Greek dialects of the historic period.[11]

Such theories are also connected with the idea that the Mycenaean language constituted a type of a special koine representing the official language of the palace records and the ruling aristocracy. When the 'Mycenaean linguistic koine' fell into disuse after the fall of the palaces because the script was no longer used, the underlying dialects would have continued to develop in their own ways. That view was formulated by Antonin Bartonek.[12][13] Other linguists like L.R. Palmer (1980),[14] and de:Yves Duhoux (1985)[15] also support this view of the 'Mycenaean linguistic koine'.[16] (The term 'Mycenaean koine' is also used by archaeologists to refer to the material culture of the region.)

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Mycenaean Greek". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑

- Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-29037-6.

- ↑ Ventris and Chadwick (1973) pages 42–48.

- 1 2 Ventris and Chadwick (1973) page 389.

- ↑ Ventris & Chadwick (1973) page 390.

- ↑ Andrew Garrett, "Convergence in the formation of Indo-European subgroups: Phylogeny and chronology", in Phylogenetic methods and the prehistory of languages, ed. Peter Forster and Colin Renfrew (Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research), 2006, p. 140, citing Ivo Hajnal, Studien zum mykenischen Kasussystem. Berlin, 1995, with the proviso that "the Mycenaean case system is still controversial in part".

- ↑ Hooker 1980:62

- ↑ Ventris & Chadwick (1973) page 68.

- ↑ Thomas G. Palaima, "OL Zh 1: QVOVSQVE TANDEM?" Minos 37-38 (2002-2003), p. 373-85 full text

- ↑ RISCH, Ernst (1966), Les differences dialectales dans le mycenien. CCMS pp.l50-160

- 1 2 3 Lydia Baumbach (1980), A DORIC FIFTH COLUMN? (PDF)

- ↑ Bartoněk, Antonín, Greek dialectology after the decipherment of Linear B. Studia Mycenaea : proceedings of the Mycenaean symposium, Brno, 1966. Bartoněk, Antonín (editor). Vyd. 1. Brno: Universita J.E. Purkyně, 1968, pp. [37]-51

- ↑ BARTONEK, A. 1966 'Mycenaean Koine reconsidered', Cambridge Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies' (CCMS) ed. by L. R. Palmer and John Chadwick, C.U.P. pp.95-103

- ↑ Palmer, L.R. (1980), The Greek Language, London.

- ↑ Duhoux, Y. (1985), ‘Mycénien et écriture grecque’, in A. Morpurgo Davies and Y. Duhoux (eds.), Linear B: A 1984 Survey (Louvain-La-Neuve): 7–74

- ↑ Stephen Colvin, ‘The Greek koine and the logic of a standard language’, in M. Silk and A. Georgakopoulou (eds.) Standard Languages and Language Standards: Greek, Past and Present (Ashgate 2009), 33-45

References

- Chadwick, John (1958). The Decipherment of Linear B. Second edition (1990). Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-39830-4.

- Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-29037-6.

- Ventris, Michael; Chadwick, John (1953). "Evidence for Greek dialect in the Mycenaean archives". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 73: 84–103. doi:10.2307/628239. JSTOR 628239.

- Ventris, Michael and Chadwick, John (1956). Documents in Mycenaean Greek. Second edition (1973). Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-08558-6.

- Bartoněk, Antonin (2003). Handbuch des mykenischen Griechisch. Universitätsverlag C. Winter. ISBN 3-8253-1435-9.

Further reading

- Easterling, P & Handley, C. Greek Scripts: An illustrated introduction. London: Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, 2001. ISBN 0-902984-17-9

- Fox, Margalit (2013). The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code. Ecco. ISBN 978-0062228833.

External links

- Jeremy B. Rutter, "Bibliography: The Linear B Tablets and Mycenaean Social, Political, and Economic Organization"

- The writing of the Mycenaeans (contains an image of the Kafkania pebble)

- Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory (PASP)

- Markos Gavalas, MYCENAEAN (Linear B) – ENGLISH Dictionary (explorecrete.com)

- Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages

- Studies in Mycenaean Inscriptions and Dialect, glossaries of individual Mycenaean terms, tablet, and series citations