Feminist art movement in the United States

The feminist art movement in the United States began in the early 1970s and sought to promote the study, creation, understanding and promotion of women's art.

First-generation feminist artists include Judy Chicago (who coined the term feminist art), Suzanne Lacy, Sheila de Bretteville, Mary Beth Edelson, Carolee Schneeman, and Rachel Rosenthal. They were part of the Feminist art movement in the United States in the early 1970s to develop feminist writing and art.[1] The movement spread quickly through museum protests in both New York (May 1970) and Los Angeles (June 1971), via an early network called W.E.B. (West-East Bag) that disseminated news of feminist art activities from 1971 to 1973 in a nationally circulated newsletter, and at conferences such as the West Coast Women’s Artists Conference held at California Institute of the Arts (January 21–23, 1972) and the Conference on Women in the Visual Arts, at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. (April 20–22, 1972).[2]

1970s

For us, there weren’t women in the galleries and museums, so we formed our own galleries, we curated our own exhibitions, we formed our own publications, we mentored one another, we even formed schools for feminist art. We examined the content of the history of art, and we began to make different kinds of art forms based on our experiences as women. So it was both social and something even beyond; in our case, it came back into our own studios.[3]

The Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s, within the second wave of feminism, "was a major watershed in women's history and the history of art" and "the personal is political" was its slogan.[4]

Key activities

Maintenance Art—Proposal for an Exhibition

In 1969 Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote a manifesto entitled Maintenance Art—Proposal for an Exhibition, challenging the domestic role of women and proclaiming herself a "maintenance artist". Maintenance, for Ukeles, is the realm of human activities that keep things going, such as cooking, cleaning and child-rearing and her performances in the 1970s included the cleaning of art galleries.[5]

Art Workers' Coalition demands equal representation for women

A demand for equality in representation for female artists was codified in the Art Workers' Coalition's (AWC) Statement of Demands, which was developed in 1969 and published in definitive form in March 1970. The AWC was set up to defend the rights of artists and force museums and galleries to reform their practices. While the coalition sprung up as a protest movement following Greek kinetic sculptor Panagiotis "Takis" Vassilakis's physical removal of his work Tele-Sculpture(1960) from a 1969 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, it quickly issued a broad list of demands to 'art museums in general'.

Alongside calls for free admission, better representation of ethnic minorities, late openings and an agreement that galleries would not exhibit an artwork without the artist's consent, the AWC demanded that museums 'encourage female artists to overcome centuries of damage done to the image of the female as an artist by establishing equal representation of the sexes in exhibitions, museum purchases and on selection committees'.[6]

Initial feminist art classes

The first women's art class was taught in the fall of 1970 at Fresno State College, now California State University, Fresno, by artist Judy Chicago. It became the Feminist Art Program, a full 15-unit program, in the Spring of 1971. This was the first feminist art program in the United States. Fifteen students studied under Chicago at Fresno State College: Dori Atlantis, Susan Boud, Gail Escola, Vanalyne Green, Suzanne Lacy, Cay Lang, Karen LeCocq, Jan Lester, Chris Rush, Judy Schaefer, Henrietta Sparkman, Faith Wilding, Shawnee Wollenman, Nancy Youdelman, and Cheryl Zurilgen. Together, as the Feminist Art Program, these women rented and refurbished an off-campus studio at 1275 Maple Avenue in downtown Fresno. Here they collaborated on art, held reading groups, and discussion groups about their life experiences which then influenced their art. Later, Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro reestablished the Feminist Art Program (FAP) at California Institute of the Arts. After Chicago left for Cal Arts, the class at Fresno State College was continued by Rita Yokoi from 1971 to 1973, and then by Joyce Aiken in 1973, until her retirement in 1992.[nb 1]

The Fresno Feminist Art Program served as a model for other feminist art efforts, such as Womanhouse, a collaborative feminist art exhibition and the first project produced after the Feminist Art Program moved to the California Institute of the Arts in the fall of 1971. Womanhouse, like the Fresno project, also developed into a feminist studio space and promoted the concept of collaborative women's art.[7]

The Feminist Studio Workshop was founded in Los Angeles in 1973 by Judy Chicago, Arlene Raven, and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville as a two-year feminist art program. Women from the program were instrumental in finding and creating the Woman's Building, the first independent center to showcase women's art and culture.

Art historian Lowery Sims established the Feminist Art Program in Los Angeles.[8]

Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?

In 1971, the art historian Linda Nochlin published the article "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" in Woman in Sexist Society, which was later reprinted in ArtNews, where she claimed that there were no "great" women artists at that time, nor in history. By omission, this inferred that artists like Georgia O'Keeffe and Mary Cassatt were not considered great. She stated why she felt that there were no great women artists and what organizational and institutional changes needed to take place to create better opportunities for women.[9]

The author Lucy Lippard and others identified three tasks to further the understanding and promotion of works by women:[10]

- Find and present current and historic art works by women

- Develop a more informal language for writing about art by women

- Create theories about the meanings behind women's art and create a history of their works.

Approaches

In California, the approach to improve the opportunities for women artists focused on creating venues, such as the Woman's Building and the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW), located with the Woman's Building. Gallery spaces, feminist magazine offices, a bookstore, and a cafe were some of the key uses of the Feminist Studio Workshop.[11]

Organizations like A.I.R. Gallery and Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) were formed in New York to provide greater opportunity for female artists and protest for to include works of women artist in art venues that had very few women represented, like Whitney Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. In 1970 there was a 23% increase in the number of women artists, and the previous year there was a 10% increase, due to Whitney Annual (later Whitney Biennial) protests.[11]

The New York Feminist Art Institute opened in June 1979 at 325 Spring Street in the Port Authority Building. The founding members and the initial board of directors were Nancy Azara, Miriam Schapiro, Selena Whitefeather, Lucille Lessane, Irene Peslikis and Carol Stronghilos.[12] A board of advisers was established of accomplished artists, educators and professional women.[12] For instance, feminist writer and arts editor at Ms. Magazine Harriet Lyons was an adviser from its start.[13]

Three Weeks in May

In 1977, Suzanne Lacy and collaborator Leslie Labowitz, combined performance art with activism in Three Weeks in May on the steps of Los Angeles City Hall. The performance, which included a map of rapes in the city, and self-defense classes highlighted sexual violence against women.[14]

Organizations and efforts

| Year | Title | Event | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) | Protest | Women Artists in Revolution, initially a group within the Art Workers' Coalition, protested the lack of representation of women artists' works in museums in 1969,[15] and operated only for a few years. Its members formed the Women's Interart Center.[16][nb 2] |

| 1970 | Women's Interart Center | Founded | The Women's Interart Center in New York, founded by 1970 in New York City, is still in operation. The Women Artists in Revolution group evolved into the Women's Interart Center, which was a workshop that fostered multidisciplinary approaches, an alternative space and community center - the first of its kind in New York.[17] |

| 1970 | Ad Hoc Women Artists' Committee | Founded | The Ad Hoc Women Artists' Committee (AWC) formed[nb 3] to address the Whitney Museum's exclusion of women artists but expanded its focus over time. Committee members included Lucy Lippard, Faith Ringgold and others.[17] The Women's Art Registry was created in 1970 to provide information about artists and their works and "counter curatorial bias and ignorance." It was maintained in several locations after the group disbanded in 1971. The registry, a model for other resource initiatives, is now maintained at Rutgers University's Mabel Smith Douglass Library.[18] |

| 1971 | Los Angeles Council of Women Artists | Protest | In response to the 1971 Art and Technology exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), an ad hoc group of women organized, calling themselves the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists. They researched the number of women included in exhibitions at LACMA and issued a June 15, 1971 report, in which they protested sexual inequality in the artworld and that lack of art works from women at the museum's "Art and Technology" exhibition.[19][20] They set a precedent for the Guerrilla Girls and other feminist groups.[20] |

| 1971[21] | Where We At (WWA)[22] | Founded | Women artists of color also began organizing, founding groups such as the African American group Where We At (WWA) and the Chicana group Las Mujeres Muralistas in order to gain visibility for artists who had been excluded or marginalized on the basis of both their sex and racial or ethnic identity.[22][23] |

| 1972 | A.I.R. Gallery | Founded | A collective gallery formed in New York and remains in operation.[15][nb 4][24] |

| 1972 | Women's Caucus for Art | Founded | Women's Caucus for Art, an offshoot of the College Art Association was founded in 1972 at the San Francisco Conference. A WCA conference is held annually and there are chapters in most areas of the U.S.[25] |

| 1972[26] | Women's Video Festival | Held festivals | The Women's Video Festival was held yearly for a number of years in New York City.[27] Many women artists continue to organize working groups, collectives, and nonprofit galleries in various locales around the world. |

| 1973 | Washington Women's Arts Center | Founded | Washington, DC, an artist-run inter-arts center opened with exhibits, writing workshops, a newsletter and quarterly literary journal Womansphere, as well as business workshops, lectures including Kathryn Anne Porter's final public lecture. The center operated through 1991. Founders included artists Barbara Frank, Janis Goodman, Kathryn Butler, and Sarah Hyde, writer Ann Slayton Leffler and art historian Josephine Withers. |

| 1973 | The Woman's Building | Founded | Los Angeles, CA was the first independent center for women's culture. It included the Feminist Studio Workshop was founded by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, art historian Arlene Raven, and Judy Chicago in 1973.[7][28] [nb 5] |

| 1973 | Womanspace | Founded | Womanspace was an artist‐run gallery opened to the public on January 27, 1973, in a converted laundromat in Los Angeles. It resulted from the energy and ideas made tangible by the work of the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists, Womanhouse, the West Coast Women Artists conference, and other feminist actions happening throughout the city. According to the first issue of Womanspace Journal (February/March 1973), the founders included Lucy Adelman, Miki Benoff, Sherry Brody, Carole Caroompas, Judy Chicago, Max Cole, Judith Fried, Gretchen Glicksman (director of Womanspace), Elyse Grinstein, Linda Levi, Joan Logue, Mildred Monteverdi, Beverly O’Neill, Fran Raboff, Rachel Rosenthal, Betye Saar, Miriam Schapiro, Wanda Westcoast, Faith Wilding, and Connie Zehr. Womanspace moved to the Woman’s Building later in 1973, and closed in 1974.[29] |

| 1973 | Artemesia | Founded | A collective gallery formed in Chicago.[15][30][nb 4] |

| 1973[31] | Las Mujeres Muralistas[22] | Founded | Women artists of color also began organizing, founding groups such as the African American group Where We At (WWA) and the Chicana group Las Mujeres Muralistas in order to gain visibility for artists who had been excluded or marginalized on the basis of both their sex and racial or ethnic identity.[22][23] |

| 1973 | Women's Art Registry of Minnesota | Founded | WARM started as a women's art collective in 1973 and ran the WARM Gallery in Minneapolis from 1976 to 1991.[32] |

| 1975 | Spiderwoman Theater | Founded | The theater was created to tell stories from an urban perspective. It is named after the Hopi goddess of creation whose objective is to "assist humans in maintaining balance in all things."[33] |

| 1979 | New York Feminist Art Institute | Founded | Founding members: Nancy Azara, Lucille Lessane, Miriam Schapiro, Irene Peslikis [34] |

Publications

The Feminist Art Journal was a feminist art publication that was produced from 1972 to 1977, and was the first stable, widely read journal of its kind. Beginning in 1975 there were scholarly publications about feminism, feminist art and historic women's art, most notably Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist by Judy Chicago; and Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975) by Susan Brownmiller; Woman Artists: 1550-1950 (1976) about Linda Nochlin and Ann Sutherland Harris's exhibition; From the Center: Feminist Essays in Women's Art (1976) by Lucy Lippard; Of Woman Born, by Adrienne Rich, When God Was a Woman (1976) by Merlin Stone; By Our Own Hands (1978) by Faith Wilding; Gyn/Ecology (1978) by Mary Daly; and Woman and Nature by Susan Griffin.[35]

In 1977, both Chrysalis and Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics began publication.[35][36][nb 6]

1980s

Feminist art evolved during the 1980s, with a trend away from experiential works and social causes. Instead, there was a trend toward works based upon Postmodern theory and influenced by psychoanalysis. Inequal representation in the artworld was a continuing issue.[11]

Key activities

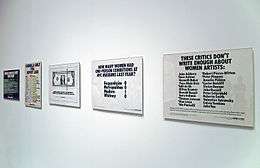

Guerrilla Girls

Guerrilla Girls was formed by 7 women artists in the spring of 1985 in response to the Museum of Modern Art's exhibition "An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture", which opened in 1984. The exhibition was the inaugural show in the MoMA's newly renovated and expanded building, and was planned to be a survey of the most important contemporary artists.[37]

The Guerrilla Girls have researched sexism and created artworks at the request of various people and institutions, among others, the Istanbul Modern, Istanbul, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Arts, Rotterdam and Fundación Bilbao Arte Fundazioa, Bilbao. They have also partnered with Amnesty International, contributing pieces to a show under the organization's "Protect the Human" initiative.[38]

Mass communication

To address the inequity faced by women artists, graphic mass communication, using refined slogans and graphics was a vehicle by which Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer sought to increase awareness.[11]

Publications

- Feminist Art Journal

- Genders: Feminist Art and (Post)Modern Anxieties[39]

- M/E/A/N/I/N/G had 20 issues (1986-1996)[40] and 5 on-line issues (2002-2011)[41]

- Woman's Art Journal (1980–present)[42]

- Heresies[43]

- n.paradoxa (1998–present)[44]

- LTTR[45]

- Meridians[46]

- The Journal of Women and Performance[47]

1990s

Key activities

Bad Girls

Bad Girls (Part I) and Bad Girls (Part II) were a 1994 pair of exhibitions at New Museum in New York, curated by Marcia Tucker. A companion exhibition, Bad Girls West was curated by Marcia Tanner and exhibited at UCLA's Wright Gallery the same year.[48][49][50]

Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party in Feminist Art History

Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party in Feminist Art History, a 1996 exhibition and text curated and written by Amelia Jones, re-exhibited Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party for the first time since 1988. It was presented by the UCLA Armand Hammer Museum.[51]

2000s

Key activities

WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution

The 2007 exhibition, WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, focused on the feminist art movement. It was organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and traveled to PS1 Contemporary Art Center in New York. WACK! featured by 120 artists from 21 countries, covering the period of 1965-1980.[52]

A Studio of Their Own

A Studio of Their Own: The Legacy of the Fresno Feminist Experiment was performed on the California State University, Fresno campus at the Phebe Conley Art Gallery in 2009. It was a retrospective that paid homage to the women from the 1970s who were part of the first women's art program.[53]

The Feminist Art Project

The Feminist Art Project website and information portal was founded at Rutgers University in 2006. A resource for artists and scholars in the United States, it publishes a calendar of events and runs conferences, discussions and education projects. It describes itself as "a strategic intervention against the ongoing erasure of women from the cultural record".[54]

Feminist art curatorial practices

History

Feminist art curating practices are within a museumism genre, which is a deconstructing of the museum space by curator/artist where the museum looks at itself or the artist/curator looks at the museum.

"If artists as curators of their own exhibition is no longer uncommon, neither is the artist-created museum or collection . . . These artists use museological practices to confront the ways in which museums rewrite history through the politics of collecting and presentation ... However, their work often inadvertently reasserts the validity of the museum" (Corrin, 1994, p. 5).[55][56]

Katy Deepwell documents feminist curating practice and feminist art history with a theoretical foundation that feminist curating is not biologically determinate.[57]

Characteristics

Feminist art curatorial practices are collaborative and reject the notion of an artist as an individual creative genius.[58][59][60]

Examples

- The Out of Here exhibition[61] is an example of feminist art curatorial practice.

- Womanhouse

- Teatro Chicana: A Collective Memoir and Selected Plays highlights El Movimiento and Chicana women’s civil rights movements representing their varied communities and histories.[62]

2010s

Key activities

The documentary film !Women Art Revolution was played at New York's IFC Center beginning June 1, 2011, before opening around the country.[63][64]

The Los Angeles Woman's Building was the subject of a major exhibition in 2012 at the Ben Maltz Gallery at Otis College of Art and Design called Doin' It in Public, Feminism and Art at the Woman's Building. It included oral histories on video, emphemera, and artists' projects. It was part of the Getty initiative Pacific Standard Time.

Now Be Here was a project from August 28, 2016, where 733 female and female identifying women came together in Los Angeles to be photographed together to show solidarity.[65]

See also

- Feminist art criticism

- Feminist art movement

- Feminist pornography

- Feminist Porn Award

- Feminism in the United States

- Gender equality

- Go Topless Day

- Pattern and Decoration art movement, related to feminist art movement

- Sex-positive feminism

- Where We At Black Women Artists (WWA)

Notes

- ↑ Aiken opened the all-women's co-op Gallery 25 with her students, developed the Fresno Art Museum's Council of 100 and the Distinguished Women Artist Series, which helped develop programming and exhibitions about women at the museum.[7]

- ↑ Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) formed to address the under representation of women artist's work in museums. In 1969 the published a list of demands, including "Museums should encourage female artists to overcome the centuries of damage done to the image of the female as an artist by establishing equal representation of the sexes in shows, museum purchases, and on selection committees."[16]

- ↑ Lippard said that the group was founded in 1971.[15]

- 1 2 Collective galleries such as A.I.R. Gallery in New York (1972–present) and Artemesia in Chicago were formed to provide visibility for art by feminist artists. The strength of the feminist movement allowed for the emergence and visibility of many new types of work by women but also helped facilitate a range of new practices by men.[15]

- ↑ Many of the feminist artists and designers from CalArts joined other feminist artists at the Woman's Building, an important center of the west coast feminist artist movement in the 1970s and 1980s in which meetings, workshops, performances, and exhibitions regularly took place. Womanspace Gallery relocated there. During the first year, there were national conferences on feminist film, writing, ceramics, among others.

- ↑ Chrysalis Magazine (1977–80), was organized out of the Los Angeles Woman's Building.

References

- ↑ Thomas Patin & Jennifer McLerran (1997). Artwords: A Glossary of Contemporary Art Theory. Westport, CT: Greenwood. p. 55. Retrieved 8 January 2014. via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Moravec, Michelle (2012). "Toward a history of feminism, art, and social movements in the United States". Frontiers: A Journal of Women's Studies, special issue: Feminist Art and Social Movements: Beyond NY/LA. University of Nebraska Press via JSTOR. 33 (2): 22–54. doi:10.5250/fronjwomestud.33.2.0022.

- ↑ "Where Fine Art Meets Craft: The Accessible Works of Joyce Kozloff". American Association of University Women. August 28, 2013.

- ↑ Norma Broude; Mary D. Garrard (1996). The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 88–103. ISBN 9780810926592. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ↑ Jon Bird, Michael Newman, Rewriting Conceptual Art, Reaktion Books, 1999, p114-5. ISBN 1-86189-052-4

- ↑ Harrison, Charles (2000). Art in theory (Repr. ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Blackwell. pp. 901–2. ISBN 0-631-16575-4.

- 1 2 3 Dr. Laura Meyer; Nancy Youdelman. "A Studio of Their Own: The Legacy of the Fresno Feminist Art Experiment". A Studio of their Own. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ↑ Arlene Raven (1991). "The Last Essay on Feminist Criticism". In Arlene Raven; Cassandra L. Langer; Joanna Frueh. Feminist Art Criticism: An Anthology. New York: Icon Editions. pp. 229–230. Retrieved 8 January 2014. via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Arlene Raven (1991). "The Last Essay on Feminist Criticism". In Arlene Raven; Cassandra L. Langer; Joanna Frueh. Feminist Art Criticism: An Anthology. New York: Icon Editions. pp. 41–42. Retrieved 8 January 2014. via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Arlene Raven (1991). "The Last Essay on Feminist Criticism". In Arlene Raven; Cassandra L. Langer; Joanna Frueh. Feminist Art Criticism: An Anthology. New York: Icon Editions. p. 100. Retrieved 8 January 2014. via Questia (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 "Feminist art movement". The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- 1 2 Fernanda Perrone, Amy Dawson, and Caroline T. Caviness. Inventory to the Records of the New York Feminist Art Institute, 1976-1990. Administrative History. Rutgers. July 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ↑ Barbara J. Love. Feminists who Changed America, 1963-1975. University of Illinois Press; 2006. ISBN 978-0-252-03189-2.

- ↑ Karen Rosenberg (March 28, 2008). "Turning Stereotypes Into Artistic Strengths". New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lippard, Lucy R. From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women's Art. New York: Dutton, 1976. p. 42

- 1 2 Julie Ault; Social Text Collective; Drawing Center (New York, N.Y.) (2002). Alternative Art, New York, 1965-1985: A Cultural Politics Book for the Social Text Collective. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-8166-3794-2.

- 1 2 Julie Ault; Social Text Collective; Drawing Center (New York, N.Y.) (2002). Alternative Art, New York, 1965-1985: A Cultural Politics Book for the Social Text Collective. U of Minnesota Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8166-3794-2.

- ↑ Julie Ault; Social Text Collective; Drawing Center (New York, N.Y.) (2002). Alternative Art, New York, 1965-1985: A Cultural Politics Book for the Social Text Collective. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-8166-3794-2.

- ↑ Female Artists, Past and Present. Women's History Research Center. 1974. p. 11.

- 1 2 "Los Angeles Council of Women Artists Report". Getty Center. June 15, 1971. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ↑ "Abundant Evidence: Black Women Artists of the 1960s and 1970s" (PDF). Amherst College. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Mark, Lisa Gabrielle (2008). WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution. Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles.

- 1 2 Burgess Fuller, Diana (2002). Art/Women/California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Meredith A.Brown 'The Balance Sheet: A.I.R. Gallery and Government Funding' n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal vol. 27 (Jan 2011) pp.29-37

- ↑ "40th Anniversary Celebration" (PDF). National Women's Caucus for Art. 2012. p. 2. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ↑ Alexandra Juhasz (2001). Women of Vision: Histories in Feminist Film and Video. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-8166-3371-5.

- ↑ John D. H. Downing; John Derek Hall Downing (2011). Encyclopedia of Social Movement Media. SAGE Publications. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7619-2688-7.

- ↑ Lippard, Lucy R. From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women's Art. New York: Dutton, 1976. p. 84

- ↑ "Checklist of the WB Exhibition" (PDF). Otis College of Art and Design. 2012.

- ↑ Nancy A. Naples; Karen Bojar (2 December 2013). Teaching Feminist Activism: Strategies from the Field. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-317-79499-8.

- ↑ Karen Mary Davalos (2001). Exhibiting Mestizaje: Mexican (American) Museums in the Diaspora. UNM Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8263-1900-5.

- ↑ Gardner-Huggett, Joanna (2008). "Review: WARM: A Feminist Art Collective in Minnesota by Joanna Inglot". Woman's Art Journal. 29 (1): 64–66. JSTOR 20358154.

- ↑ Janet McAdams; Geary Hobson; Kathryn Walkiewicz (9 October 2012). The People Who Stayed: Southeastern Indian Writing After Removal. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8061-8575-0.

- ↑ Katie Cercone 'The New York Feminist Art Institute' n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal vol. 22 (July 2008) pp.49-56 New York Feminist Art Institute

- 1 2 Moira Roth (1991). "Visions and Re-Visions: Rosa Luxemburg and the Artist's Mother". In Arlene Raven; Cassandra L. Langer; Joanna Frueh. Feminist Art Criticism: An Anthology. New York: Icon Editions. p. 109. Retrieved 8 January 2014. via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics(1977–92), now the subject of a documentary film, The Heretics.

- ↑ Brenson, Michael (April 21, 1984). "A Living Artists Show at the Modern Museum". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ "Press Releases | Amnesty International UK". Amnesty.org.uk. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "''Genders: Feminist Art and (Post)Modern Anxieties''". Genders.org. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

- ↑ "M/E/A/N/I/N/G, 1986-1996 (ed. Susan Bee and Mira Schor) | Jacket2". jacket2.org. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- ↑ "M/E/A/N/I/N/G, ed. Susan Bee and Mira Schor". Writing.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

- ↑ "''Woman's Art Journal''". Womansartjournal.org. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

- ↑ "THE HERETICS : Directed by Joan Braderman, Produced by Crescent Diamond". Heresiesfilmproject.org. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Official home page for n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal; feminist art; contemporary women artists; feminist art theory; feminist artists; writing about women artists; KT press". Ktpress.co.uk. ISSN 1461-0434. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "LTTR". LTTR. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism". Smith.edu. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Issues | Women & Performance". Womenandperformance.org. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Bad Girls (Part I)". The New Museum Digital Archive. The New Museum. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Roberta (January 21, 1994). "Review/Art; A Raucous Caucus Of Feminists Being Bad". New York Times. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ Knight, Christopher (February 8, 1994). "ART REVIEW : 'Bad Girls': Feminism on Wry : Tone Bemusedly Subversive in West Coast Edition of N.Y. Show". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ Reilly, Maura. "The Dinner Party: Tour and Home". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ "WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution". MOCA. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ "Feminist art retrospective opens Aug. 26". August 11, 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ The Feminist Art Project. Rutgers University. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ↑ CORRIN, L. G. (1993). Mining the museum: An installation confronting history. Curator: The Museum Journal, 36(4), 302-313. doi:10.1111/j.2151-6952.1993.tb00804.x

- ↑ Klebesadel, Helen (2005). Reframing studio art production and critique. In Janet Marstine (Ed.), New museum theory and practice an introduction (pp. 247-265). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- ↑ Deepwell, Katy (2005). Feminist curatorial strategies and practices since the 1970s. In Janet Marstine (Ed.), New museum theory and practice an introduction (pp. 64-84). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- ↑ Parker, R., & Pollock, G. (1981). Old mistresses: Women, art and ideology. New York: Pantheon Books.

- ↑ Curatorial Collectives and Feminist Politics in 21st Century Europe: An Interview with Kuratorisk Aktion

- ↑ Hedlin Hayden, Malin & Sjoholm Skrubbe, Jessica (Eds.). (2010). Feminisms is still our name: Seven essays on historiography and curatorial practices. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- ↑ Out of Here. Judy Chicago site. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ Garcia, L. E., Gutierrez, S. M., & Nuñez, F. (2008). Teatro chicana: A collective memoir and selected plays. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- ↑ Yerman, Marcia G. (March 14, 2011). "!Women Art Revolution at MoMA". Huffington Post. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ↑ Voynar, Kim (June 1, 2011). "Review: !Women Art Revolution". Movie City News. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Now Be Here: Women artists make a stand, and a photo". ART AND CAKE. 2016-08-29. Retrieved 2016-09-26.

Further reading

- Armstrong, Carol and Catherine de Zegher (eds.), Women Artists at the Millennium, The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2006.

- Bee, Susan and Mira Schor (eds.), The M/E/A/N/I/N/G Book, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2000.

- Bloom, Lisa Jewish Identities in American Feminist Art: Ghosts of Ethnicity London & New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Brown, Betty Ann, ed. Expanding Circles: Women, Art & Community. New York: Midmarch, 1996.

- Broude, Norma and Mary Garrard The Power of Feminist Art: Emergence,Impact and Triumph of the American Feminist Art Movement New York, Abrams, 1994.

- Butler, Connie. WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art. 2007.

- Chicago, Judy. Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist. New York: Viking, 1996.

- Chicago, Judy. The Dinner Party: A Symbol of Our Heritage. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1979.

- Chicago, Judy. Embroidering Our Heritage: The Dinner Party. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1979.

- Cottingham, Laura. How Many 'Bad' Feminists Does It Take to Change a Light Bulb? New York: Sixty Percent Solution. 1994.

- Cottingham, Laura. Seeing Through the Seventies: Essays on Feminism and Art. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: G+B Arts, 2000.

- Farris, Phoebe (ed) Women Artists of Colour: A bio-critical Sourcebook to 20th Century Artists in the Americas Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1990.

- Frostig, Karen and Kathy A. Halainka eds. Blaze: Discourse on Art, Women and Feminism USA, Cambridge Scholar, 2007.

- Hammond, Harmony Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History New York: Rizzoli International Publications Inc, 2000.

- Frueh, Joanna, Cassandra L. Langer, and Arlene Raven, eds. New Feminist Criticism: Art, Identity, Action, 1993.

- Hess, Thomas B. and Elizabeth C. Baker, eds. Art and Sexual Politics: Women's Liberation, Women Artists, and Art History. New York, Macmillan, 1973

- Isaak, Jo Anna . Feminism and Contemporary Art: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Laughter. New York: Routledge, 1996.

- King-Hammond, Leslie (ed) Gumbo Ya Ya: Anthology of Contemporary African-American Women Artists New York: Midmarch Press, 1995.

- Lippard, Lucy The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Feminist Essays on Art New York: New Press, 1996.

- Meyer, Laura, ed. A Studio of Their Own: The Legacy of the Fresno Feminist Experiment. Fresno, Calif.: Press at California State University, Fresno, 2009.

- Perez, Laura Elisa Chicana art : the politics of spiritual and aesthetic altarities Durham, N.C. : Duke University Press ; Chesham: 2007.

- Phelan, Peggy. Art and Feminism. London: Phaidon, 2001.

- Raven, Arlene. Crossing Over: Feminism and Art of Social Concern. 1988

- Siegel, Judy Mutiny and the Mainstream: Talk that Changed Art,1975-1990 New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 1992.

- Schor, Mira. Wet: On Painting, Feminism, and Art Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 1997

- Wilding. Faith. By Our Own Hands: The Women Artist's Movement, Southern California, 1970-1976.