History of Germans in Russia, Ukraine and the Soviet Union

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (~3 million) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| ~2.3 million | |

| 394,138 (2010)[1] | |

| 178,409 (2009)[2] | |

| 33,302 (2001)[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Roman Catholicism, Protestantism[4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Germans in Kazakhstan, Baltic Germans, Germans from Russia, Estonian Swedes | |

The German minority in Russia, Ukraine, and the Soviet Union, self-termed as Russaki or Russlanddeutsche was created from several sources and in several waves. The 1914 census put the number of Germans living in The Russian Empire at 2,416,290.[5] In 1989, the German population of the Soviet Union was roughly 2 million.[6] By the next decade (1999–2002), the population will have fallen to the half, to roughly one million: 597,212 Germans were enumerated in Russia (2002 Russian census), making Germans the fifth largest ethnic group in that country; 353,441 Germans in Kazakhstan and 21,472 in Kyrgyzstan (1999);[7] 33,300 Germans lived in Ukraine (2001 census).[8]

In the Russian Empire, Germans were strongly represented among royalty, aristocracy, large land owners, military officers, and the upper echelons of the imperial service, engineers, scientists, artists, physicians, and the bourgeoisie in general. The Germans of Russia did not necessarily speak Russian; they spoke German, while French was often the language of the high aristocracy. However, today's Russian Germans mostly speak Russian as they are in the gradual process of assimilation. As such, many may not necessarily be fluent in German. Consequently, Germany has recently strictly limited their immigration, and a decline in the number of Germans in the Russian Federation has moderated as they no longer emigrate to Germany and as Kazakh Germans move to Russia instead of Germany. As conditions for the Germans generally deteriorated in the late 19th century and early 20th century, many Germans migrated from Russia to the Americas and elsewhere, collectively known as Germans from Russia.

Germans in Russia and Ukraine

The earliest German settlement in Russia dates back to the reign of Vasili III, Grand Prince of Moscow from 1505 to 1533. A handful of German and Dutch craftsmen and traders were allowed to establish themselves in Moscow's German Quarter (Немецкая слобода, or Nemetskaya sloboda), providing essential technical skills in the capital. Gradually, this policy extended to a few other major cities. In 1682, Moscow had about 200,000 citizens; 18,000 of them were Nemtsy, which means either "German" or "western foreigner".

The international community located in the German Quarter greatly influenced Peter the Great (reigned 1682-1725), and his efforts to transform Russia into a more modern European state are believed to have derived in large part from his experiences among Russia's established Germans. By the late 17th-century, foreigners were no longer so rare in Russian cities, and Moscow's German Quarter had lost its ethnic character by the end of that century.

Vistula Germans

Through wars and the partitions of Poland, Prussia acquired an increasing amount of northern, western, and central Polish territory. The Vistula River flows south to north, to near Danzig (now Gdańsk). Germans and Dutch settled its valley starting from the Baltic Sea and moving further south with time. Eventually, Prussia acquired most of the Vistula's watershed, and the central portion of then-Poland became South Prussia. Its existence was brief - 1793 to 1806, but by its end many German settlers had established Protestant agricultural settlements within its earlier borders. From already-Prussian Silesia to the southwest some German Roman Catholics also entered the region. The 1935 "Breyer Map" shows the distribution of German settlements in what became central Poland.

Napoleon's victories ended the short existence of South Prussia. The French Emperor incorporated it and other territories into the Duchy of Warsaw. After Napoleon's defeat in 1815, however, the Duchy was divided. The western Posen region again became part of Prussia, while what is now central Poland became the Russian client-state Congress Poland. Many Germans remained in this central region, maintaining their middle-German Prussian dialect, similar to the Silesian dialect, and their religions. With World Wars I and II, the eastern front hovered on their doorstep and conscription increased. The Vistula Germans' migrations from Congress Poland increased. Some became Polonized, however, and their descendants remain in Poland. After World War II, many of those who retained their German language and customs were forcibly expelled by the Russians and the Poles, with the loss of all their property.

Volga Germans

%2C_1742%2C_Russian_Museum.jpg)

Tsarina Catherine II was a German, born in Stettin in Pomerania, now Szczecin in Poland. She proclaimed open immigration for foreigners wishing to live in the Russian Empire on July 22, 1763, marking the beginning of a much larger presence for Germans in the Empire. German colonies in the lower Volga river area were founded almost immediately afterward. These early colonies were attacked during the Pugachev uprising, which was centred on the Volga area, but they survived the rebellion.

German immigration was motivated in part by religious intolerance and warfare in central Europe as well as by frequently difficult economic conditions. Catherine II's declaration freed German immigrants from military service (imposed on native Russians) and from most taxes. It placed the new arrivals outside of Russia's feudal hierarchy and granted them considerable internal autonomy. Moving to Russia gave German immigrants political rights that they would not have possessed in their own lands. Religious minorities found these terms very agreeable, particularly Mennonites from the Vistula River valley. Their unwillingness to participate in military service, and their long tradition of dissent from mainstream Lutheranism and Calvinism, made life under the Prussians very difficult for them. Nearly all of the Prussian Mennonites emigrated to Russia over the following century, leaving no more than a handful in Prussia.

Other German minority churches took advantage of Catherine II's offer as well, particularly Evangelical Christians like the Baptists. Although Catherine's declaration forbade them from proselytising among members of the Orthodox church, they could evangelize Russia's Muslim and other non-Christian minorities.

German colonization was most intense in the Lower Volga, but other areas also saw an influx. The area around the Black Sea received many German immigrants, and the Mennonites favoured the lower Dniepr river area, around Ekaterinaslav (now Dnepropetrovsk) and Aleksandrovsk (now Zaporizhzhia).

In 1803 Catherine II's grandson, Tsar Alexander I, reissued her proclamation. In the chaos of the Napoleonic wars, the response from Germans was enormous. Ultimately, the Tsar imposed minimum financial requirements on new immigrants, requiring them to either have 300 gulden in cash or special skills in order to come to Russia.

The abolition of serfdom in the Russian Empire in 1863 created a shortage of labour in agriculture and motivated new German immigration, particularly from increasingly crowded central European states, where there was no longer enough fertile land for full employment in agriculture.

Furthermore, a sizable part of Russia's ethnic Germans migrated into Russia from its Polish possessions. The 18th-century partitions of Poland (1772–1795) dismantled the Polish-Lithuanian state, dividing it between Austria, Prussia and Russia. Many Germans already living in those parts of Poland transferred to Russia, dating back to medieval and later migrations. Many Germans in Congress Poland migrated further east into Russia between then and World War I, particularly in the aftermath of the Polish insurrection of 1830. The Polish insurrection in 1863 added a new wave of German emigration from Poland to those who had already moved east, and led to the founding of extensive German colonies in Volhynia. When Poland reclaimed its independence in 1918 after World War I, it ceased to be a source of German emigration to Russia, but by then many hundreds of thousands of Germans had already settled in enclaves across the Russian Empire.

Germans settled in the Caucasus area from the beginning of the 19th century and in the 1850s expanded into the Crimea. In the 1890s new German colonies opened in the Altay mountain area in Russian Asia (see Mennonite settlements of Altai). German colonial areas continued to expand in Ukraine as late as the beginning of World War I.

According to the first census of the Russian Empire in 1897, about 1.8 million respondents reported German as their mother tongue.

Black Sea Germans

The Black Sea Germans - including the Bessarabian Germans and the Dobrujan Germans - settled the territories of the northern bank of the Black Sea in present-day Ukraine in the 18th and 19th centuries. Catherine the Great had gained this land for Russia through her two wars with the Ottoman Empire (1768–1774) and from the annexation of the Crimean Khanates (1783). The area of settlement was not settled as compactly as that of the Volga territory, rather it became home to a chain of colonies. The first German settlers arrived in 1787, first from West Prussia, then later from Western and Southwestern Germany, and from the Warsaw area. Also many Germans, beginning in 1803, immigrated from the northeastern area of Alsace west of the Rhine, and settled roughly 30 miles northeast of Odessa (city) in Ukraine, forming several enclaves that quickly multiplied with daughter colonies springing up nearby.[9]

Crimea Germans

From 1783 onwards a systematic settlement of Russians, Ukrainians, and Germans in the Crimean Peninsula (in what was then the Crimean Khanate) aimed to dilute the native population of the Crimean Tatars.

In 1939, two years before their deportation to Central Asia, around 60,000 of the 1.1 million inhabitants of Crimea were German.

Under perestroika in the late 1980s Germans gained the right to return to the peninsula.

Caucasus Germans

A German minority of about 100,000 people existed in the Caucasus region, in areas such as the North Caucasus, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. In 1941 Joseph Stalin ordered all inhabitants with a German father to be deported, mostly to Siberia or Kazakhstan.

Germans of Ukraine

- Volhynia

The migration of Germans into Volhynia (as of 2013 covering northwestern Ukraine from a short distance west of Kiev to the border with Poland) occurred under significantly different conditions than those going to other parts of Russia. By the end of the 19th century Volhynia had over 200,000 German settlers.[10] Their migration began at the encouragement of local noblemen, often Polish landlords, who wanted to develop their significant land-holdings in the area. Probably 75% or more of them originated from Congress Poland, with the balance coming directly from other regions such as East and West Prussia, Pomerania, Posen, Württemberg, and Galicia among others. Although the noblemen themselves offered certain perks for the move, the Germans of Volhynia received none of the special tax and military service freedoms granted to the Germans in other areas.

The settlement started as a trickle shortly after 1800. A surge occurred after the first Polish rebellion of 1831 but by 1850, they were still only about 5000 in number. The largest migration came after the second Polish rebellion of 1863 when they began to flood into the area by the thousands until they reached their peak at about 200,000 in the year 1900. The vast majority of these Germans were of the Lutheran (in Europe they were referred to as Evangelicals) faith. Limited numbers of Mennonites from the lower Vistula River region settled in the south part of Volhynia, while Baptists and Moravian Brethren also arrived, mostly settling northwest of Zhitomir. Another major difference between the Germans here and in other parts of Russia is that the other Germans tended to settle in larger communities. The Germans in Volhynia were scattered about in over 1400 villages. Though the population peaked in 1900, many Germans had already begun leaving Volhynia in the late 1880s for North and South America.

Between 1911 and 1915 a small group of Volhynian German farmers (36 families - more than 200 people) chose instead to move to Eastern Siberia, making use of the resettlement subsidies of the Stolypin reform of 1906-1911. They settled in three villages (Pikhtinsk, Sredne-Pikhtinsk, and Dagnik) in what is today Zalari District of Irkutsk Oblast, where they became known as the "Bug Hollanders". They apparently were not using German any more, but rather spoke Ukrainian and Polish, and used Lutheran Bibles that had been printed in East Prussia, in Polish, but in fraktur. Their descendants, still bearing German names, continue to live in the district into the 21st century.[11]

Decline of the Russian Germans

The decline of the Russian German community started with the reforms of Alexander II. In 1871, he repealed the open-door immigration policy of his ancestors, effectively ending any new German immigration into the Empire. Although the German colonies continued to expand, they were driven by natural growth and by the immigration of Germans from Poland.

The Russian nationalism that took root under Alexander II served as a justification for eliminating in 1871 the bulk of the tax privileges enjoyed by Russian Germans, and after 1874 they were subjected to military service. Only after long negotiations, Mennonites, traditionally a pacifist denomination, were allowed to serve alternative service in the form of work in forestry and the medical corps. The resulting disaffection motivated many Russian Germans, especially members of traditionally dissenting churches, to migrate to the United States and Canada, while many Catholics chose Brazil and Argentina. They moved primarily to the American Great Plains and western Canada, especially North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado; to Canada Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and Alberta; to Brazil, especially Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul; and to Argentina, especially South of Buenos Aires Province, Entre Ríos Province and La Pampa Province. North Dakota and South Dakota attracted primarily Odessa (Black Sea area) Germans from Russia while Nebraska and Kansas attracted mainly Volga Germans from Russia. The majority of Volhynia Germans chose Canada as their destination with significant numbers later migrating to the United States. Smaller settlement pockets also occurred in other regions such as Volga and Volhynian Germans in southwestern Michigan, Volhynian Germans in Wisconsin, and Congress Poland and Volhynian Germans in Connecticut.

After 1881, Russian Germans were required to study Russian in school and lost all their remaining special privileges. Many Germans remained in Russia, particularly those who had done well as Russia began to industrialise in the late 19th century. Russian Germans were disproportionately represented among Russia's engineers, technical tradesmen, industrialists, financiers and large land owners.

World War I was the first time Russia went to war against Germany since the Napoleonic era, and Russian Germans were quickly suspected of having enemy sympathies. The Germans living in the Volhynia area were deported to the German colonies in the lower Volga river in 1915 when Russia started losing the war. Many Russian Germans were exiled to Siberia by the Tsar's government as enemies of the state - generally without trial or evidence. In 1916, an order was issued to deport the Volga Germans to the east as well, but the Russian Revolution prevented this from being carried out.

The loyalties of Russian Germans during the revolution varied. While many supported the royalist forces and joined the White Army, others were committed to Alexander Kerensky's Provisional Government, to the Bolsheviks, and even to smaller forces like Nestor Makhno's. Russian Germans - including Mennonites and Evangelicals - fought on all sides in the Russian Revolution and Civil War. Although some Russian Germans were very wealthy, others were quite poor and sympathised strongly with their Slavic neighbours. Educated Russian Germans were just as likely to have leftist and revolutionary sympathies as the ethnically Russian intelligentsia.

In the chaos of the Russian Revolution and the civil war that followed it, many ethnic Germans were displaced within Russia or emigrated from Russia altogether. The chaos surrounding the Russian Civil War was devastating to many German communities, particularly to religious dissenters like the Mennonites. Many Mennonites hold the forces of Nestor Makhno in Ukraine particularly responsible for large-scale violence against their community.

This period was also one of regular food shortages, caused by famine and the lack of long distance transportation of food during the fighting. Coupled with the typhus epidemic and famine of the early 1920s,[12] as many as a third of Russia's Germans may have perished. Russian German organisations in the Americas, particularly the Mennonite Central Committee, organised famine relief in Russia in the late 1920s. As the chaos faded and the Soviet Union's position became more secure, many Russian Germans simply took advantage of the end of the fighting to emigrate to the Americas. Emigration from the Soviet Union came to a halt in 1929 by Stalin's decree, leaving roughly one million Russian Germans within Soviet borders.

The Soviet Union seized the farms and businesses of Russian Germans, along with all other farms and businesses, when Stalin ended Vladimir Lenin's New Economic Policy in 1929 and began the forced collectivization of agriculture and liquidation of large land holdings.

Nonetheless, Soviet nationalities policy had, to some degree, restored the institutions of Russian Germans in some areas. In July 1924, the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was founded, giving the Volga Germans some autonomous German language institutions. The Lutheran church, like nearly all religious affiliations in Russia, was ruthlessly suppressed under Stalin. But, for the 600,000-odd Germans living in the Volga German ASSR, German was the language of local officials for the first time since 1881.

As a result of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Stalin decided to deport the German Russians to internal exile and forced labor in Siberia and Central Asia. It is evident that, at this point, the regime considered national minorities with ethnic ties to foreign states, such as Germans, potential fifth columnists. On August 12, 1941, the Central Committee of the Communist Party decreed the expulsion of the Volga Germans, allegedly for treasonous activity, from their autonomous republic on the lower Volga. On September 7, 1941, the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was abolished and about 438,000 Volga Germans were deported. In subsequent months, an additional 400,000 ethnic Germans were deported to Siberia from their other traditional settlements such as the Ukraine and the Crimea.

The Soviets were not successful in expelling all German settlers living in the Western and Southern Ukraine, however, due to the rapid advance of the Wehrmacht (German Army). The secret police, the NKVD, was able to deport only 35% of the ethnic Germans from the Ukraine. Thus in 1943, the Nazi German census registered 313,000 ethnic Germans living in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union. With the Soviet re-conquest, the Wehrmacht evacuated about 300,000 German Russians and brought them back to the Reich. Because of the provisions of the Yalta Agreement, all former Soviet citizens living in Germany at war’s end had to be repatriated, most by force. More than 200,000 German Russians were deported, against their will, by the Allies and sent to the Gulag . Thus, shortly after the end of the war, more than one million ethnic Germans from Russia were in special settlements and labor camps in Siberia and Central Asia. It is estimated that 200,000 to 300,000 died of starvation, lack of shelter, over-work, and disease during the 1940s.[13]

On November 26, 1948, Stalin made the banishment permanent, declaring that Russia's Germans were permanently forbidden from returning to Europe, but this was rescinded after his death in 1953. Many Russian Germans returned to European Russia, but quite a few remained in Soviet Asia.

Although the post-Stalin Soviet state no longer persecuted ethnic Germans as a group, their Soviet republic was not re-founded. Many Germans in Russia largely assimilated and integrated into Russian society. There were some 2 million ethnic Germans in the Soviet Union in 1989.[14] Soviet Union census revealed in 1989 that 49% of the German minority named German their mother tongue. According to the 1989 Soviet census, 957,518 citizens of German origin, or 6% of total population, lived in Kazakhstan,[15] and 841,295 Germans lived in Russia including Siberia.[16]

Perestroika opened the Soviet borders and witnessed the beginnings of a massive emigration of Germans from the Soviet Union. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, large numbers of Russian Germans took advantage of Germany's liberal law of return to leave the harsh conditions of the Soviet successor states.[17] The German population of Kyrgyzstan has practically disappeared, and Kazakhstan has lost well over half of its roughly one million Germans. The drop in the Russian Federation's German population was smaller, but still significant. A very few Germans returned to one of their ancestral provinces: about 6,000 settled in Kaliningrad Oblast (former East Prussia).

Russian Germans and the Perestrojka

Since migrating to Russia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Germans had adopted many of the Slavic traits and cultures and formed a special group known as "rossiskie nemtsy", or Russian Germans.[18] Recently, Russian Germans have become of national interest to Germany and to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).[19] Although ethnic Germans were no longer persecuted, their pre-Bolshevik lives and villages were not re-founded. Many Germans integrated into Soviet society where they now continue to live. The displaced Germans are unable to return to their ancestral lands in the Volga River Valley or the Black Sea regions, because in many instances, those villages no longer exist after being destroyed during Stalin's regime. In 1990, approximately 45,000 Russian Germans, or 6% of the population, lived in the former German Volga Republic.[20] During the late twentieth century, three-quarters of Russian Germans were living in Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tadzhikistan and Uzbekistan), South-West Siberia and Southern Urals.[21]

Starting in the 1970s, a push-pull effect began that would influence where Russian Germans would eventually live. Because of a bad economy, tensions increased between autochthonous groups and recently settled ethnic minorities living in Central Asia.[22] This strain worsened after the Afghanistan War began in 1979.[22] Germans and other Europeans felt culturally and economically pressured to leave these countries, and moved to the Russian Republic. This migration continued into the 1990s.[22]

During Perestroika in the 1980s, the Soviet borders were opened and the beginnings of a massive migration of Germans from the Soviet Union occurred. Entire families, and even villages, would leave their homes and relocate together in Germany or Austria.[22] This was because they needed to show the German Embassy certain documents, such as a family Bible, as proof that their ancestors were originally from Germany.[23] This meant if a family member stayed in the Soviet Union, but then decided to leave later, they would be unable to because they would no longer have the necessary paperwork. Also, Russian German villages were pretty much self-sustaining so if an individual that was necessary for that community, such as a teacher, mechanic or blacksmith left, then the entire village might disappear because it was hard to find a replacement for these vital community members.[24]

Legal and economic pull factors contributed to Russian Germans decision to move to Germany. They were given special legal status of Aussiedler (exiles from former German territories or of German descent) which gave them instant German citizenship, the right to vote, unlimited work permit, the flight from Moscow to Frankfurt (with all of their personal belongings and household possessions), job training, and unemployment benefits for three years.[25]

Russian Germans from South-West Siberia received a completely different treatment than the Germans living in Central Asia. Local authorities were persuading Germans to stay by creating two self-governing districts.[19]

The All-Union Society Wiedergeburt (Renaissance) was founded in 1989 to encourage Russian Germans to move back to, and restore the Volga Republic.[26] This plan was not successful because Germany interfered with the discussions and created diplomatic friction, which resulted in Russian opposition to this project. A couple of those problems were the two sides could not put aside their differences and agree on certain principles such as the meaning of the word "rehabilitation".[27] They also neglected the economic reasons why Russia wanted to entice Russian Germans back to the Volga. In 1992, Russian Germans and Russian officials finally agreed on a plan, but Germany did not approve it.[28]

On 21 February 1992, Boris Yeltsin, President of the Russian Federation, signed a German-Russian Federation agreement with Germany to restore citizenship to Russian Germans.[29] This Federal Program intended to gradually restore the homeland of Russian Germans, and their descendants, in the former Republic of Volga, thus encouraging Russian Germans to immigrate back to Russia.[30] It would also guarantee the national and cultural identity of Russian Germans would be preserved, such as their culture, language and religion.[31] At the same time, it would not block or regulate their right to leave if they decide to do so at a later point.[32]

Events for a separate territory proceeded differently in Siberia, because financially stable Russian German settlements already existed. Siberian officials were economically driven to keep their skilled Russian German citizens and not see them leave for other republics or countries.[28] In the late 1980s, 8.1% of Russian Germans lived in the county of Altay in South-West Siberia and they controlled one-third of profitable farms.[33]

In early 1990, a few ideas offered to the Officer of Exiles (the bureau in charge of emigrants after arriving in Germany) in order to retain Russian Germans, or to promote their return included the suggestion that the necessary important village specialists (mechanics, teachers, doctors, etc.) should be offered incentives such as Trade Associations and additional training in order to keep, or to attract them to Russia. Russian German schools and universities should also be reopened. A third idea is to establish a financial institution that would motivate individuals to buy homes, and start farms or small businesses.[34] Unfortunately, proposed initiatives have not gained traction and have not been instituted due to corruption, incompetency and inexperience.[35] The Association for Germans Abroad (VDA) contracted with the business Inkoplan, to move families from Central Asia at vastly inflated costs. This resulted in VDA and Inkoplan personnel pocketing the difference.[36] Examples of incompetency and inexperience included: VDA falsely projected the idea all Russian Germans wanted to leave their present homes and lives and move to the Volga region where they would start over.[36] The Home Office was not fluent in the Russian language or familiar with foreign cultures abroad and this created many misunderstandings between various groups.[37] Because of these actions by the Home Office, the migration back to Germany continues. Over 140,000 individuals migrated to Germany from CIS in 1990 and 1991, and almost 200,000 people migrated in 1992.[24]

Demographics

| Historical Russian/Soviet German population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1897 | 1,790,489 | — |

| 1926 | 1,238,549 | −30.8% |

| 1939 | 1,427,232 | +15.2% |

| 1959 | 1,619,655 | +13.5% |

| 1970 | 1,846,317 | +14.0% |

| 1979 | 1,936,214 | +4.9% |

| 1989 | 2,038,603 | +5.3% |

| Source: | ||

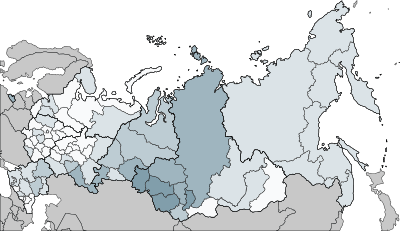

In the 2010 Russian census, 394,138 Germans were enumerated, down from 597,212 in 2002, making Germans the 20th largest ethnic group in Russia. There are approximately 300,000 Germans living in Siberia.[39] In addition, the same census found that there are 2.9 million citizens who understand the German language (although many of these are ethnic Russians or Yiddish-speaking Jews who had learned the language). Prominent ethnic Germans in modern Russia include Viktor Kress, governor of Tomsk Oblast since 1991 and German Gref[40] Minister of Economics and Trade of Russia since 2000. Out of the 597,212 Germans enumerated in 2002, 68% lived in Asian federal districts and 32% lived in European federal districts. The Siberian Federal District, at 308,727 had the largest ethnic German population. But even in this federal district, they formed only 1.54% of the total population. The federal subjects with largest ethnic German populations were Altay Krai (79,502), Omsk Oblast (76,334), Novosibirsk (47,275), Kemerovo (35,965), Chelyabinsk (28,457), Tyumen (27,196), Sverdlovsk (22,540), Krasnodar (18,469), Orenburg (18,055), Volgograd (17,051), Tomsk (13,444), Saratov (12,093) and Perm Krai (10,152).[41] Although emigration to Germany is no longer common, and some Germans move from Kazakhstan to Russia, the number of Germans in Russia continues to fall, mainly due to assimilation with the majority Russians as younger Germans marry Russians and count their children in the census as Russian.

Another indication of assimilation is the fact that Russian Orthodoxy has become the largest faith among Russian Germans, and Lutheranism has largely been abandoned. According to a recent survey, 18% of Russian Germans consider themselves Russian Orthodox, 7.2% Catholic, and only 3.2% mainline Protestant (presumably Lutheran). Also, 34% are unaffiliated, 18% are atheist, 5% generic Christian, 2% other Orthodox, 2% neopagan, and 1.2% Pentecostal.[4]

In 2011, the Kaluga Oblast included ethnic Germans living in the former republics of USSR, under the federal program for the return of compatriots to Russia.[42]

According to the 1989 census there were 100,309 Germans living in Kyrgyzstan. According to the most recent census data (1999), there were 21,472 Germans in Kyrgyzstan. The German population in Tajikistan was 38,853 in 1979.[43]

In Germany, there are an estimated 2.3 million German Russians, who have established one of the largest Russian-speaking communities outside of the former Soviet Union along with Israel's.

Education

Several German international schools for expatriates living in the former Soviet Union are in operation.

Russia:

Georgia:

- Deutsche Internationale Schule Tiflis

Ukraine:

Germans in the Baltics

The German presence on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea dates back to the Middle Ages when traders and missionaries started arriving from central Europe. The German-speaking Livonian Brothers of the Sword conquered most of what is now Estonia and Latvia (the former Livonia) in the early 13th century. In 1237, the Brothers of the Sword were incorporated into the Teutonic Knights.

During Peter the Great's rule Russia gained control over much of the Baltics from Sweden in the Great Northern War at the beginning of the 18th century, but left the German nobility in control. Until the Russification policies of the 1880s, the German community and its institutions were intact and protected under the Russian Empire. The Baltic German nobility were very influential in the Russian Tsar's army and administration.

The reforms of Alexander III replaced many of the traditional privileges of the German nobility with elected local governments and more uniform tax codes. Schools were required to teach Russian, and the Russian nationalist press began targeting segregated Germans as unpatriotic and insufficiently Russian. Baltic Germans were also the target of Estonian and Latvian nationalist movements.

In late 1939 (after the start of the Second World War), the entire remaining Baltic German community was repatriated by Adolf Hitler to areas Nazi Germany had invaded in western Poland (especially in the Warthegau). The "legal" basis for this was agreed in the August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the subsequent Nazi-Soviet population transfers which had given the Soviet Union a green light to invade and annex Latvia and Estonia in 1940.

Only a handful of Baltic Germans remained under Soviet rule after 1945 mainly among those few who refused Germany's call to leave the Baltics.

Famous Russian-Germans

- Catherine the Great - Empress of Russia

- Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse) - Empress Consort of Russia

- Adam Johann von Krusenstern (Ivan Fedorovich Kruzenshtern) - navigator and naval explorer (1770–1846)

- Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen (Faddey Faddeyevich Bellinsgauzen) - navigator, explorer of the Antarctic (1778–1852)

- Karl Nesselrode - count and diplomat (1780–1862)

- Karl Ernst Claus - chemist (1796–1864)

- Heinrich Lenz - physicist (1804 – 1865)

- Maria Alexandrovna Ulyanova (née Maria Blank) - Mother of Vladimir Lenin (1835 — 1916)

- Vyacheslav von Plehve (Vyacheslav Pleve) - Minister of the Interior (1846–1904)

- Vladimir Pachmann - pianist (1848–1933)

- Sergei Yulyevich Witte - Ministry of Ways and Communications + Finance, chairman of the Committee of Ministers (1849-1915)

- Paul von Rennenkampf - Imperial army general during World War I (1854–1918)

- Eduard Toll - explorer of the Arctic (1858–1902)

- Pyotr Schmidt - Russian naval officer and 1905 revolutionary (1867-1906)

- Olga Knipper-Chekhova - actress, wife of Anton Chekhov (1868–1959)

- Vsevolod Meyerhold (Karl Kasimir Theodor Meyerhold) - actor and theatre director (1874—1940)

- Reinhold Glière (Reinhold Ernst Glier) - composer (1875–1956)

- Gustav Klinger - communist politician (1876–1937)

- Max Vasmer - linguist, author of the Etymological dictionary of the Russian language (1886–1962)

- Immanuel Winkler (1886–1932) - Pastor, official representative of Black Seas Germans

- Friedrich Zander - rocket engineer (1887–1933)

- Oskar Anderson - statistician (1887–1960)

- Otto Schmidt - geophysicist and statesman (1891-1956)

- Alfred Rosenberg - one of Nazi Germany's leaders, tried at Nuremberg (1893–1946)

- Vasiliy Ulrikh (Vasiliy Ulrich) - Soviet political judge (1889–1951)

- Nikolai Erdmann - dramatist (1900—1970)

- Vilyam Genrikhovich Fischer Rudolf Abel - Soviet intelligence officer (1903–1971)

- Tatjana Iwanowna Peltzer - actress (1904–1992)

- Boris Rauschenbach - physicist and engineer (1915–2001)

- Sviatoslav Richter - pianist (1915–1997)

- Patriarch Alexy II (Alexey Ridiger) - primate of the Russian Orthodox Church (1929–2008)

- Alfred Schnittke - composer (1934–1998)

- Anna German (Anna Hörmann) - singer (1936–1982)

- Jeanna Friske / born Jeanna Vladimirovna Kopylova (Жанна Фриске) - singer, model, actress, socialite (1974-2015)

- Alisa Freindlich - actress

- Eduard Rossel - governor of Sverdlovsk Oblast

- Viktor Kress - governor of Tomsk Oblast

- German Gref (Hermann Gräf) - Minister of Economics and Trade

- Alexei Miller - Gazprom CEO

- Edgar Gess - football player

- Peter Neustädter - football player

- Andreas Wolf - football player (born 1982)

- Alexander Merkel - football player (born 1992)

- Georgy Boos - governor of Kaliningrad Oblast

- Julia Neigel - singer and songwriter

- Angelina Grün - volleyball player

- Wladimir Köppen - meteorologist

- Irina Mikitenko - long-distance runner

- Dennis Siver - mixed martial arts fighter

- Brad Wall - Premier of Saskatchewan

- Helene Fischer - singer, moderater

See also

- House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov

- Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

- Nazi-Soviet population transfers

- Crimean Goths

- Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Russian Mennonite

- Mennonite settlements of Altai

- German operation of the NKVD

- Germans of Kazakhstan

- Bessarabia Germans

- Russians in Germany

- Deutsche Nationalkreis Asowo

- Deutsche Nationalkreis Halbstadt

Notes

- ↑ 2010 Russian Census

- ↑ 2009 Kazakhstan Census

- ↑ 2001 Ukrainian Census

- 1 2 "Главная страница проекта "Арена" : Некоммерческая Исследовательская Служба "Среда"". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ L Schaitberger. "The Long March of the Innocents". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Bonn Urges Russia to Restore Land for Its Ethnic Germans, New York Times

- ↑ Case Studies Database

- ↑ 2001 Ukrainian Population Census

- ↑ Karl Stumpp, "The Emigration From Germany to Russia in the Years 1763-1862"

- ↑ The Germans from Volhynia and Russian Poland

- ↑ Olga Solovyova (Ольга Соловьева) "Bug 'Hollanders'" (БУЖСКИЕ ГОЛЕНДРЫ) (Russian)

- ↑ The Volga Germans and the Famine of 1921

- ↑ Ulrich Merten, Voices from the Gulag, the Oppression of the German Minority in the Soviet Union, (American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Lincoln, Nebraska,2015)ISBN 978-0-692-60337-6, pp 2,3,166

- ↑ Germans from Russia Heritage Collection

- ↑ KAZAKHSTAN: Special report on ethnic Germans, IRIN Asia

- ↑ "Russia - Other Ethnic Groups". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "gms - 50. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Medizinische Informatik, Biometrie und Epidemiologie (gmds) 12. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Epidemiologie (dae) - External causes of death in a cohort of Aussiedler from the former Soviet Union, 1990-2002". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Helmut Kluter, "People of German Descent in CIS States – Areas of Settlement, Territorial Autonomy and Emigration," GeoJournal, Vol. 31, No. 4 (December 1993): 421.

- 1 2 Kluter, 419.

- ↑ Kluter, 425.

- ↑ Kluter, 421.

- 1 2 3 4 Kluter, 423.

- ↑ Kluter 428.

- 1 2 Kluter, 428.

- ↑ Kluter, 429.

- ↑ Kluter, 424.

- ↑ Kluter, 419, 427.

- 1 2 Kluter, 427.

- ↑ "Germany-Russian Federation: Protocol of Collaboration on the Gradual Restoration of Citizenship to Russian Germans, with Decree of the Russian Federation," International Legal Materials, Vol. 31, No. 6 (November 1992): 1301, 1302

- ↑ "Germany-Russian Federation:" 1301.

- ↑ Björn Arp, International Norms and Standards for the Protection of National Minorities: Bilateral and Multilateral Texts for Commentary, (Leiden, Boston, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2008), 288. "Germany-Russian Federation:" 1301.

- ↑ Arp, 288.

- ↑ Kluter, 422

- ↑ Kluter, 433, 434.

- ↑ Kluter, 431 - 433.

- 1 2 Kluter, 431.

- ↑ Kluter, 432.

- ↑ "Приложение Демоскопа Weekly". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2016-04-27.

- ↑ "Orientation - Siberian Germans". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ As transliterated from Russian, in German, his name would probably be written as Hermann Graef.

- ↑ http://www.perepis2002.ru/ct/doc/English/4-2.xls

- ↑ "Калужская область готова принять немцев, переселившихся из стран СНГ". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ J. Otto Pohl. "Otto's Random Thoughts". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

External links

- Germans From Russia Heritage Society

- American Historical Society of Germans from Russia

- German-Russian Settlement Map

- Manifesto of the Empress Catherine II issued July 22, 1763

- Vistula Germans - history and map settlements by religion

- Germans from Volhynia - genealogy, culture, history

- JewishGen's Gazetteer