Green Revolution

|

| Agriculture |

|---|

| History |

| Farming |

| Other types |

| Related |

| Lists |

| Categories |

|

|

|

The Green Revolution refers to a set of research and development of technology transfer initiatives occurring between the 1930s and the late 1960s (with prequels in the work of the agrarian geneticist Nazareno Strampelli in the 1920s and 1930s), that increased agricultural production worldwide, particularly in the developing world, beginning most markedly in the late 1960s.[1] The initiatives resulted in the adoption of new technologies, including:

...new, high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of cereals, especially dwarf wheats and rices, in association with chemical fertilizers and agro-chemicals, and with controlled water-supply (usually involving irrigation) and new methods of cultivation, including mechanization. All of these together were seen as a 'package of practices' to supersede 'traditional' technology and to be adopted as a whole.[2]

The initiatives, led by Norman Borlaug, the "Father of the Green Revolution", who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, credited with saving over a billion people from starvation, involved the development of high-yielding varieties of cereal grains, expansion of irrigation infrastructure, modernization of management techniques, distribution of hybridized seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and pesticides to farmers.

The term "Green Revolution" was first used in 1968 by former US Agency for International Development (USAID) director William Gaud, who noted the spread of the new technologies: "These and other developments in the field of agriculture contain the makings of a new revolution. It is not a violent Red Revolution like that of the Soviets, nor is it a White Revolution like that of the Shah of Iran. I call it the Green Revolution."[3]

History

Green Revolution in Mexico

It has been argued that “during the twentieth century two 'revolutions' transformed rural Mexico: the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) and the Green Revolution (1950–1970).[4] With the support of the Mexican government, the U.S. government, the United Nations, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Rockefeller Foundation, Mexico made a concerted effort to transform agricultural productivity, particularly with irrigated rather than dry-land cultivation in its northwest, to solve its problem of lack of food self-sufficiency.[5] In the center and south of Mexico, where large-scale production faced challenges, agricultural production languished.[6] Increased production meant food self-sufficiency in Mexico to feed its growing and urbanizing population, with the number of calories consumed per Mexican increasing.[7] Technology was seen as a valuable way to feed the poor, and would relieve some pressure of the land redistribution process.[8]

Mexico was not merely the recipient of Green Revolution knowledge and technology, but was an active participant with financial support from the government for agriculture as well as Mexican agronomists (agrónomos). Although the Mexican Revolution had broken the back of the hacienda system and land reform in Mexico had by 1940 distributed a large expanse of land in central and southern Mexico, agricultural productivity had fallen. During the administration of Manuel Avila Camacho (1940–46), the government put resources into developing new breeds of plants and partnered with the Rockefeller Foundation.[9] In 1943, the Mexican government founded the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), which became a base for international agricultural research.

Agriculture in Mexico had been a sociopolitical issue, a key factor in some regions’ participation in the Mexican Revolution. It was also a technical issue, which the development of a cohort trained agronomists, who were to advise peasants how to increase productivity.[10] In the post-World War II era, the government sought development in agriculture that bettered technological aspects of agriculture in regions that were not dominated by small-scale peasant cultivators. This drive for transforming agriculture would have the benefit of keeping Mexico self-sufficient in food and in the political sphere with the Cold War, potentially stem unrest and the appeal of Communism.[9] Technical aid can be seen as also serving political ends in the international sphere. In Mexico, it also served political ends, separating peasant agriculture based on the ejido and considered one of the victories of the Mexican Revolution, from agribusiness that requires large-scale land ownership, irrigation, specialized seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides, machinery, and a low-wage paid labor force.

The government created the Mexican Agricultural Program (MAP) to be the lead organization in raising productivity. One of their successes was wheat production, with varieties the agency’s scientists helped create dominating wheat production as early as 1951 (70%), 1965 (80%), and 1968 (90%).[11] Mexico became the showcase for extending the Green Revolution to other areas of Latin America and beyond, into Africa and Asia. New breeds of maize, beans, along with wheat produced bumper crops with proper inputs (such as fertilizer and pesticides) and careful cultivation. Many Mexican farmers who had been dubious about the scientists or hostile to them (often a mutual relationship of discord) came to see the scientific approach to agriculture worth adopting.[12]

Green Revolution in Rice: IR8 and the Philippines

In 1960, the Government of the Republic of the Philippines with the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation established IRRI (International Rice Research Institute). A rice crossing between Dee-Geo-woo-gen and Peta was done at IRRI in 1962. In 1966, one of the breeding lines became a new cultivar, IR8.[13] IR8 required the use of fertilizers and pesticides, but produced substantially higher yields than the traditional cultivars. Annual rice production in the Philippines increased from 3.7 to 7.7 million tons in two decades.[14] The switch to IR8 rice made the Philippines a rice exporter for the first time in the 20th century.[15]

Green Revolution's start in India

In 1961, India was on the brink of mass famine. [16] Norman Borlaug was invited to India by the adviser to the Indian minister of agriculture C. Subramaniam. Despite bureaucratic hurdles imposed by India's grain monopolies, the Ford Foundation and Indian government collaborated to import wheat seed from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). Punjab was selected by the Indian government to be the first site to try the new crops because of its reliable water supply and a history of agricultural success. India began its own Green Revolution program of plant breeding, irrigation development, and financing of agrochemicals.[17]

India soon adopted IR8 – a semi-dwarf rice variety developed by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) that could produce more grains of rice per plant when grown with certain fertilizers and irrigation. In 1968, Indian agronomist S.K. De Datta published his findings that IR8 rice yielded about 5 tons per hectare with no fertilizer, and almost 10 tons per hectare under optimal conditions. This was 10 times the yield of traditional rice.[18] IR8 was a success throughout Asia, and dubbed the "Miracle Rice". IR8 was also developed into Semi-dwarf IR36.

In the 1960s, rice yields in India were about two tons per hectare; by the mid-1990s, they had risen to six tons per hectare. In the 1970s, rice cost about $550 a ton; in 2001, it cost under $200 a ton.[19] India became one of the world's most successful rice producers, and is now a major rice exporter, shipping nearly 4.5 million tons in 2006.

Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research - CGIAR

In 1970, foundation officials proposed a worldwide network of agricultural research centers under a permanent secretariat. This was further supported and developed by the World Bank; on 19 May 1971, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research(CGIAR) was established. co-sponsored by the FAO, IFAD and UNDP. CGIAR has added many research centers throughout the world.

CGIAR has responded, at least in part, to criticisms of Green Revolution methodologies. This began in the 1980s, and mainly was a result of pressure from donor organizations.[20] Methods like Agroecosystem Analysis and Farming System Research have been adopted to gain a more holistic view of agriculture.

Brazil's agricultural revolution

Brazil's vast inland cerrado region was regarded as unfit for farming before the 1960s because the soil was too acidic and poor in nutrients, according to Norman Borlaug. However, from the 1960s, vast quantities of lime (pulverised chalk or limestone) were poured on the soil to reduce acidity. The effort went on for decades; by late 1990s, between 14 million and 16 million tonnes of lime were being spread on Brazilian fields each year. The quantity rose to 25 million tonnes in 2003 and 2004, equalling around five tonnes of lime per hectare. As a result, Brazil has become the world's second biggest soybean exporter. Soybeans are also widely used in animal feed, and the large volume of soy produced in Brazil has contributed to Brazil's rise to become the biggest exporter of beef and poultry in the world.[21] Several parallels can also be found in Argentina's boom in soybean production as well.[22]

Problems in Africa

There have been numerous attempts to introduce the successful concepts from the Mexican and Indian projects into Africa.[23] These programs have generally been less successful. Reasons cited include widespread corruption, insecurity, a lack of infrastructure, and a general lack of will on the part of the governments. Yet environmental factors, such as the availability of water for irrigation, the high diversity in slope and soil types in one given area are also reasons why the Green Revolution is not so successful in Africa.[24]

A recent program in western Africa is attempting to introduce a new high-yielding 'family' of rice varieties known as "New Rice for Africa" (NERICA). NERICA varieties yield about 30% more rice under normal conditions, and can double yields with small amounts of fertilizer and very basic irrigation. However, the program has been beset by problems getting the rice into the hands of farmers, and to date the only success has been in Guinea, where it currently accounts for 16% of rice cultivation.[25]

After a famine in 2001 and years of chronic hunger and poverty, in 2005 the small African country of Malawi launched the "Agricultural Input Subsidy Program" by which vouchers are given to smallholder farmers to buy subsidized nitrogen fertilizer and maize seeds.[26] Within its first year, the program was reported to have had extreme success, producing the largest maize harvest of the country's history, enough to feed the country with tons of maize left over. The program has advanced yearly ever since. Various sources claim that the program has been an unusual success, hailing it as a "miracle".[27]

Agricultural production and food security

Technologies

The Green Revolution spread technologies that already existed, but had not been widely implemented outside industrialized nations. These technologies included modern irrigation projects, pesticides, synthetic nitrogen fertilizer and improved crop varieties developed through the conventional, science-based methods available at the time.

The novel technological development of the Green Revolution was the production of novel wheat cultivars. Agronomists bred cultivars of maize, wheat, and rice that are generally referred to as HYVs or "high-yielding varieties". HYVs have higher nitrogen-absorbing potential than other varieties. Since cereals that absorbed extra nitrogen would typically lodge, or fall over before harvest, semi-dwarfing genes were bred into their genomes. A Japanese dwarf wheat cultivar (Norin 10 wheat), which was sent to Washington, D.C. by Cecil Salmon, was instrumental in developing Green Revolution wheat cultivars. IR8, the first widely implemented HYV rice to be developed by IRRI, was created through a cross between an Indonesian variety named "Peta" and a Chinese variety named "Dee-geo-woo-gen".[28]

With advances in molecular genetics, the mutant genes responsible for Arabidopsis thaliana genes (GA 20-oxidase,[29] ga1,[30] ga1-3[31]), wheat reduced-height genes (Rht)[32] and a rice semidwarf gene (sd1)[33] were cloned. These were identified as gibberellin biosynthesis genes or cellular signaling component genes. Stem growth in the mutant background is significantly reduced leading to the dwarf phenotype. Photosynthetic investment in the stem is reduced dramatically as the shorter plants are inherently more stable mechanically. Assimilates become redirected to grain production, amplifying in particular the effect of chemical fertilizers on commercial yield.

HYVs significantly outperform traditional varieties in the presence of adequate irrigation, pesticides, and fertilizers. In the absence of these inputs, traditional varieties may outperform HYVs. Therefore, several authors have challenged the apparent superiority of HYVs not only compared to the traditional varieties alone, but by contrasting the monocultural system associated with HYVs with the polycultural system associated with traditional ones.[34]

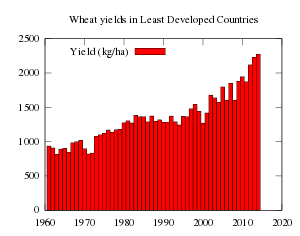

Production increases

Cereal production more than doubled in developing nations between the years 1961–1985.[35] Yields of rice, maize, and wheat increased steadily during that period.[35] The production increases can be attributed roughly equally to irrigation, fertilizer, and seed development, at least in the case of Asian rice.[35]

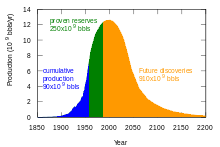

While agricultural output increased as a result of the Green Revolution, the energy input to produce a crop has increased faster,[36] so that the ratio of crops produced to energy input has decreased over time. Green Revolution techniques also heavily rely on chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides and rely on machines, which as of 2014 rely on or are derived from crude oil, making agriculture increasingly reliant on crude oil extraction.[37] Proponents of the Peak Oil theory fear that a future decline in oil and gas production would lead to a decline in food production or even a Malthusian catastrophe.[38]

Effects on food security

The effects of the Green Revolution on global food security are difficult to assess because of the complexities involved in food systems.

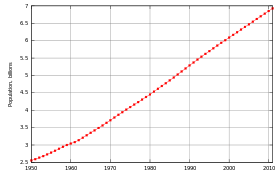

The world population has grown by about four billion since the beginning of the Green Revolution and many believe that, without the Revolution, there would have been greater famine and malnutrition. India saw annual wheat production rise from 10 million tons in the 1960s to 73 million in 2006.[39] The average person in the developing world consumes roughly 25% more calories per day now than before the Green Revolution.[35] Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the globe, world grain production increased by about 160%.[40]

The production increases fostered by the Green Revolution are often credited with having helped to avoid widespread famine, and for feeding billions of people.[41]

There are also claims that the Green Revolution has decreased food security for a large number of people. One claim involves the shift of subsistence-oriented cropland to cropland oriented towards production of grain for export or animal feed. For example, the Green Revolution replaced much of the land used for pulses that fed Indian peasants for wheat, which did not make up a large portion of the peasant diet.[42]

Criticism

3rd World Economic Sovereignty

A main criticism of the effects of the Green Revolution is the rising costs for many small farmers using HYV seeds, with their associated demands of increased irrigation systems and pesticides. A case study is found in India, where farmers are planting cotton seeds capable of producing Bt toxin.[43] A criticism regarding the Green Revolution are the effects regarding the widespread commercialization and market share of organisations, particularly of the phasing out of seed saving practices in favor of purchasing of seeds, and concerns regarding the financial affordability of the adoption of patented crops amongst farmers, particularly of those in the developing world.[44] This can allow larger farms, even foreign owned farming operations, to buy up local smallhold farms.

Vandana Shiva notes that this is the "second Green Revolution". The first Green Revolution, she notes, was mostly publicly-funded (by the Indian Government). This new Green Revolution, she says, is driven by private [and foreign] interest - notably MNCs like Monsanto. Ultimately, this is leading to foreign ownership over most of India's farmland.[45][46]

Food security

Malthusian criticism

Some criticisms generally involve some variation of the Malthusian principle of population. Such concerns often revolve around the idea that the Green Revolution is unsustainable,[47] and argue that humanity is now in a state of overpopulation or overshoot with regards to the sustainable carrying capacity and ecological demands on the Earth.

Although 36 million people die each year as a direct or indirect result of hunger and poor nutrition,[48] Malthus's more extreme predictions have frequently failed to materialize. In 1798 Thomas Malthus made his prediction of impending famine.[49] The world's population had doubled by 1923 and doubled again by 1973 without fulfilling Malthus's prediction. Malthusian Paul R. Ehrlich, in his 1968 book The Population Bomb, said that "India couldn't possibly feed two hundred million more people by 1980" and "Hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs."[49] Ehrlich's warnings failed to materialize when India became self-sustaining in cereal production in 1974 (six years later) as a result of the introduction of Norman Borlaug's dwarf wheat varieties.[49]

Since supplies of oil and gas are essential to modern agriculture techniques,[51] a fall in global oil supplies could cause spiking food prices in the coming decades.[52]

Famine

To some modern Western sociologists and writers, increasing food production is not synonymous with increasing food security, and is only part of a larger equation. For example, Harvard professor Amartya Sen claimed large historic famines were not caused by decreases in food supply, but by socioeconomic dynamics and a failure of public action.[53] However, economist Peter Bowbrick disputes Sen's theory, arguing that Sen relies on inconsistent arguments and contradicts available information, including sources that Sen himself cited.[54] Bowbrick further argues that Sen's views coincide with that of the Bengal government at the time of the Bengal famine of 1943, and the policies Sen advocates failed to relieve the famine.[54]

Quality of diet

Some have challenged the value of the increased food production of Green Revolution agriculture. Miguel A. Altieri, (a pioneer of agroecology and peasant-advocate), writes that the comparison between traditional systems of agriculture and Green Revolution agriculture has been unfair, because Green Revolution agriculture produces monocultures of cereal grains, while traditional agriculture usually incorporates polycultures.

These monoculture crops are often used for export, feed for animals, or conversion into biofuel. According to Emile Frison of Bioversity International, the Green Revolution has also led to a change in dietary habits, as fewer people are affected by hunger and die from starvation, but many are affected by malnutrition such as iron or vitamin-A deficiencies.[24] Frison further asserts that almost 60% of yearly deaths of children under age five in developing countries are related to malnutrition.[24]

High-yield rice (HYR), introduced since 1964 to poverty-ridden Asian countries, such as the Philippines, was found to have inferior flavor and be more glutinous and less savory than their native varieties. This caused its price to be lower than the average market value.[55]

In the Philippines the introduction of heavy pesticides to rice production, in the early part of the Green Revolution, poisoned and killed off fish and weedy green vegetables that traditionally coexisted in rice paddies. These were nutritious food sources for many poor Filipino farmers prior to the introduction of pesticides, further impacting the diets of locals.[56]

Political impact

A major critic[57] of the Green Revolution, U.S. investigative journalist Mark Dowie, writes:[58]

The primary objective of the program was geopolitical: to provide food for the populace in undeveloped countries and so bring social stability and weaken the fomenting of communist insurgency.

Citing internal Foundation documents, Dowie states that the Ford Foundation had a greater concern than Rockefeller in this area.[59]

There is significant evidence that the Green Revolution weakened socialist movements in many nations. In countries such as India, Mexico, and the Philippines, technological solutions were sought as an alternative to expanding agrarian reform initiatives, the latter of which were often linked to socialist politics.[60][61]

Socioeconomic impacts

The transition from traditional agriculture, in which inputs were generated on-farm, to Green Revolution agriculture, which required the purchase of inputs, led to the widespread establishment of rural credit institutions. Smaller farmers often went into debt, which in many cases results in a loss of their farmland.[20][62] The increased level of mechanization on larger farms made possible by the Green Revolution removed a large source of employment from the rural economy.[20] Because wealthier farmers had better access to credit and land, the Green Revolution increased class disparities, with the rich–poor gap widening as a result. Because some regions were able to adopt Green Revolution agriculture more readily than others (for political or geographical reasons), interregional economic disparities increased as well. Many small farmers are hurt by the dropping prices resulting from increased production overall. However, large-scale farming companies only account for less than 10% of the total farming capacity. This is a criticism held by many small producers in the food sovereignty movement.

The new economic difficulties of small holder farmers and landless farm workers led to increased rural-urban migration. The increase in food production led to a cheaper food for urban dwellers, and the increase in urban population increased the potential for industrialization.

Globalization

In the most basic sense, the Green Revolution was a product of globalization as evidenced in the creation of international agricultural research centers that shared information, and with transnational funding from groups like the Rockefeller Foundation, Ford Foundation, and United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Environmental impact

Biodiversity

The spread of Green Revolution agriculture affected both agricultural biodiversity (or agrodiversity) and wild biodiversity.[56] There is little disagreement that the Green Revolution acted to reduce agricultural biodiversity, as it relied on just a few high-yield varieties of each crop.

This has led to concerns about the susceptibility of a food supply to pathogens that cannot be controlled by agrochemicals, as well as the permanent loss of many valuable genetic traits bred into traditional varieties over thousands of years. To address these concerns, massive seed banks such as Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research’s (CGIAR) International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (now Bioversity International) have been established (see Svalbard Global Seed Vault).

There are varying opinions about the effect of the Green Revolution on wild biodiversity. One hypothesis speculates that by increasing production per unit of land area, agriculture will not need to expand into new, uncultivated areas to feed a growing human population.[63] However, land degradation and soil nutrients depletion have forced farmers to clear up formerly forested areas in order to keep up with production.[64] A counter-hypothesis speculates that biodiversity was sacrificed because traditional systems of agriculture that were displaced sometimes incorporated practices to preserve wild biodiversity, and because the Green Revolution expanded agricultural development into new areas where it was once unprofitable or too arid. For example, the development of wheat varieties tolerant to acid soil conditions with high aluminium content, permitted the introduction of agriculture in sensitive Brazilian ecosystems such as Cerrado semi-humid tropical savanna and Amazon rainforest in the geoeconomic macroregions of Centro-Sul and Amazônia.[63] Before the Green Revolution, other Brazilian ecosystems were also significantly damaged by human activity, such as the once 1st or 2nd main contributor to Brazilian megadiversity Atlantic Rainforest (above 85% of deforestation in the 1980s, about 95% after the 2010s) and the important xeric shrublands called Caatinga mainly in Northeastern Brazil (about 40% in the 1980s, about 50% after the 2010s — deforestation of the Caatinga biome is generally associated with greater risks of desertification). This also caused many animal species to suffer due to their damaged habitats.

Nevertheless, the world community has clearly acknowledged the negative aspects of agricultural expansion as the 1992 Rio Treaty, signed by 189 nations, has generated numerous national Biodiversity Action Plans which assign significant biodiversity loss to agriculture's expansion into new domains.

The Green Revolution has been criticized for an agricultural model which relied on a few staple and market profitable crops, and pursing a model which limited the biodiversity of Mexico. One of the critics against these techniques and the Green Revolution as a whole was Carl O. Sauer, a geography professor at the University of California, Berkeley. According to Sauer these techniques of plant breeding would result in negative effects on the country's resources, and the culture:

"A good aggressive bunch of American agronomists and plant breeders could ruin the native resources for good and all by pushing their American commercial stocks… And Mexican agriculture cannot be pointed toward standardization on a few commercial types without upsetting native economy and culture hopelessly... Unless the Americans understand that, they'd better keep out of this country entirely. That must be approached from an appreciation of native economies as being basically sound".[65]

Greenhouse gas emissions

According to a study published in 2013 in PNAS, in the absence of the crop germplasm improvement associated with the Green Revolution, greenhouse gas emissions would have been 5.2-7.4 Gt higher than observed in 1965–2004.[66] High yield agriculture has dramatics affects on the amount of carbon cycling in the atmosphere. The way in which farms are grown, in tandem with the seasonal carbon cycling of various crops, could alter the impact carbon in the atmosphere has on global warming. Wheat, rice, and soybean crops, account for a significant amount of the increase n carbon in the atmosphere over the last 50 years.[67]

Dependence on non-renewable resources

Most high intensity agricultural production is highly reliant on non-renewable resources. Agricultural machinery and transport, as well as the production of pesticides and nitrates all depend on fossil fuels.[68] Moreover, the essential mineral nutrient phosphorus is often a limiting factor in crop cultivation, while phosphorus mines are rapidly being depleted worldwide.[69] The failure to depart from these non-sustainable agricultural production methods could potentially lead to a large scale collapse of the current system of intensive food production within this century.

Health impact

The consumption of the pesticides used to kill pests by humans in some cases may be increasing the likelihood of cancer in some of the rural villages using them.[70] Poor farming practices including non-compliance to usage of masks and over-usage of the chemicals compound this situation.[70] In 1989, WHO and UNEP estimated that there were around 1 million human pesticide poisonings annually. Some 20,000 (mostly in developing countries) ended in death, as a result of poor labeling, loose safety standards etc.[71]

Pesticides and cancer

Long term exposure to pesticides such as organochlorines, creosote, and sulfate have been correlated with higher cancer rates and organochlorines DDT, chlordane, and lindane as tumor promoters in animals. Contradictory epidemiologic studies in humans have linked phenoxy acid herbicides or contaminants in them with soft tissue sarcoma (STS) and malignant lymphoma, organochlorine insecticides with STS, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), leukemia, and, less consistently, with cancers of the lung and breast, organophosphorous compounds with NHL and leukemia, and triazine herbicides with ovarian cancer.[72][73]

Punjab case

The Indian state of Punjab pioneered green revolution among the other states transforming India into a food-surplus country.[74] The state is witnessing serious consequences of intensive farming using chemicals and pesticide. A comprehensive study conducted by Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) has underlined the direct relationship between indiscriminate use of these chemicals and increased incidence of cancer in this region.[75] An increase in the number of cancer cases has been reported in several villages including Jhariwala, Koharwala, Puckka, Bhimawali, and Khara.[75]

Environmental activist Vandana Shiva has written extensively about the social, political and economic impacts of the Green Revolution in Punjab. She claims that the Green Revolution's reliance on heavy use of chemical inputs and monocultures has resulted in water scarcity, vulnerability to pests, and incidents of violent conflict and social marginalization.[76]

In 2009, under a Greenpeace Research Laboratories investigation, Dr Reyes Tirado, from the University of Exeter, UK conducted the study in 50 villages in Muktsar, Bathinda and Ludhiana districts revealed chemical, radiation and biological toxicity rampant in Punjab. Twenty percent of the sampled wells showed nitrate levels above the safety limit of 50 mg/l, established by WHO, the study connected it with high use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers.[77]

Norman Borlaug's response to criticism

Borlaug dismissed certain claims of critics, but also cautioned, "There are no miracles in agricultural production. Nor is there such a thing as a miracle variety of wheat, rice, or maize which can serve as an elixir to cure all ills of a stagnant, traditional agriculture."[78]

Of environmental lobbyists, he said:

"some of the environmental lobbyists of the Western nations are the salt of the earth, but many of them are elitists. They've never experienced the physical sensation of hunger. They do their lobbying from comfortable office suites in Washington or Brussels...If they lived just one month amid the misery of the developing world, as I have for fifty years, they'd be crying out for tractors and fertilizer and irrigation canals and be outraged that fashionable elitists back home were trying to deny them these things".[79]

However, the charge of "elitism" could also be leveled against supporters of the Green Revolution. As noted in the documentary Profits from Poison,[80] protective gear for farmers is often designed by people who have never experienced tropical climates. For example, plastic ponchos create a sauna effect if worn in high temperature/humidity, as opposed the experience of wearing them in an airconditioned office.

The New Green Revolution

Although the Green Revolution has been able to improve agricultural output in some regions in the world, there was and is still room for improvement. As a result, many organizations continue to invent new ways to improve the techniques already used in the Green Revolution. Frequently quoted inventions are the System of Rice Intensification,[81] marker-assisted selection,[82] agroecology,[83] and applying existing technologies to agricultural problems of the developing world.[84]

See also

- Agroecology

- Arab Agricultural Revolution

- British Agricultural Revolution

- Environmental issues with agriculture

- Food security

- Food sovereignty

- Genetic pollution

- Green Revolution in India

- Industrial agriculture

- Neolithic Revolution

- Plant breeding

- Virgin Lands Campaign

Notes

- ↑ Hazell, Peter B.R. (2009). The Asian Green Revolution. IFPRI Discussion Paper. Intl Food Policy Res Inst. GGKEY:HS2UT4LADZD.

- ↑ Farmer, B. H. (1986). "Perspectives on the 'Green Revolution'in South Asia". Modern Asian Studies. 20 (01): 175–199. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00013627.

- ↑ Gaud, William S. (8 March 1968). "The Green Revolution<3 Accomplishments and Apprehensions". AgBioWorld. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Joseph Cotter, Troubled Harvest: Agronomy and Revolution in Mexico, 1880–2002, Westport, CT: Praeger. Contributions in Latin American Studies, no. 22, 2003, p. 1.

- ↑ David Barkin, "Food Production, Consumption, and Policy", Encyclopedia of Mexico vol. 1, p. 494. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- ↑ James W. Wessman, "Agribusiness and Agroindustry", Encyclopedia of Mexico vol. 1, p. 29. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers 1997

- ↑ Barkin, "Food Production", p. 494.

- ↑ Jennifer, Clapp. Food. p. 34.

- 1 2 Cotter, p. 11

- ↑ Cotter, p. 10

- ↑ Cotter, p. 233.

- ↑ Cotter, p. 235

- ↑ IRRI Early research and training results (pdf)pp.106–109.

- ↑ "Rice paddies". FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Friday, 14 Jun. 1968 (14 June 1968). "Rice of the Gods". TIME. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ "India Girds for Famine Linked With Flowering of Bamboo" Check

|url=value (help). News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 13 August 2010. - ↑ "Newsroom: News Releases". CGIAR. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ↑ De Datta SK, Tauro AC, Balaoing SN (1 November 1968). "Effect of plant type and nitrogen level on growth characteristics and grain yield of indica rice in the tropics". Agron. J. 60 (6): 643–7. doi:10.2134/agronj1968.00021962006000060017x.

- ↑ Barta, Patrick (28 July 2007). "Feeding Billions, A Grain at a Time". The Wall Street Journal. pp. A1.

- 1 2 3 Oasa 1987

- ↑ The Economist. Brazilian agriculture: The miracle of the cerrado. August 26, 2010. http://www.economist.com/node/16886442

- ↑ Al Jazeera English (2013-03-13), People & Power - Argentina: The Bad Seeds, retrieved 2016-10-10

- ↑ Groniger, Wout (2009). Debating Development – A historical analysis of the Sasakawa Global 2000 project in Ghana and indigenous knowledge as an alternative approach to agricultural development (Master thesis). Universiteit Utrecht.

- 1 2 3 Emile Frison (May 2008). "Biodiversity: Indispensable resources". D+C. 49 (5): 190–3.

If there is to be a Green Revolution for Africa, it will be necessary to breed improved varieties and, indeed, livestock. That task will depend on access to the genetic resources inherent in agricultural biodiversity. However, biodiversity is also important for tackling malnutrition as well as food security.

- ↑ Dugger, Celia W. (10 October 2007). "In Africa, Prosperity From Seeds Falls Short". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Chibwana, Christopher; Fisher, Monica. "The Impacts of Agricultural Input Subsidies in Malawi". International Food Policy Research Institute. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ↑ Malawi Miracle article on the BBC website. According to the UN website on Malawi the program was highly effective. This website highlights the women farmers program. The claims of success are substantiated by Malawi government claims at Malawi National Statistics Organization site Archived 13 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. The international WaterAid organisation seems to contradict these facts with its report on plans from 2005–2010. Similarly, the Major League Gaming reported that Malawi had noted problems including lack of transparency and administrative difficulties. This follows with a recent (2010) Malawi newspaper tells of UN report Archived 8 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. with Malawi one of the lowest on the UN list of developing states, confirmed by this UN World Food Program report. Another report from the Institute for Security Studies Archived 13 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. from 2005, showed corruption still prevailing in Malawi at that time.

- ↑ Hicks, Norman (2011). The Challenge of Economic Development: A Survey of Issues and Constraints Facing Developing Countries. Bloomington,IN: AuthorHouse. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4567-6633-7 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Xu YL, Li L, Wu K, Peeters AJ, Gage DA, Zeevaart JA (July 1995). "The GA5 locus of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a multifunctional gibberellin 20-oxidase: molecular cloning and functional expression". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (14): 6640–4. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.6640X. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.14.6640. PMC 41574

. PMID 7604047.

. PMID 7604047. - ↑ Silverstone AL, Chang C, Krol E, Sun TP (July 1997). "Developmental regulation of the gibberellin biosynthetic gene GA1 in Arabidopsis thaliana". Plant J. 12 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.12010009.x. PMID 9263448.

- ↑ Silverstone AL, Ciampaglio CN, Sun T (February 1998). "The Arabidopsis RGA gene encodes a transcriptional regulator repressing the gibberellin signal transduction pathway". Plant Cell. 10 (2): 155–69. doi:10.1105/tpc.10.2.155. PMC 143987

. PMID 9490740.

. PMID 9490740. - ↑ Appleford NE; Wilkinson MD; Ma Q; et al. (2007). "Decreased shoot stature and grain alpha-amylase activity following ectopic expression of a gibberellin 2-oxidase gene in transgenic wheat". J. Exp. Bot. 58 (12): 3213–26. doi:10.1093/jxb/erm166. PMID 17916639.

- ↑ Monna L; Kitazawa N; Yoshino R; et al. (February 2002). "Positional cloning of rice semidwarfing gene, sd-1: rice "green revolution gene" encodes a mutant enzyme involved in gibberellin synthesis". DNA Res. 9 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1093/dnares/9.1.11. PMID 11939564.

- ↑ Igbozurike, U.M. (1978). "Polyculture and Monoculture: Contrast and Analysis". GeoJournal. 2 (5): 443–49. doi:10.1007/BF00156222.

- 1 2 3 4 Conway 1998, Ch. 4

- ↑ Church, Norman (1 April 2005). "Why Our Food is So Dependent on Oil". PowerSwitch. Archived from the original on 1 April 2005. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Fuel costs, drought influence price increase". Timesdaily.com. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ "Rising food prices curb aid to global poor". Csmonitor.com. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ "The end of India's green revolution?". BBC News. 29 May 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Kindall, Henery W; Pimentel, David (May 1994). "Constraints on the Expansion of the Global Food Supply". Ambio. 23 (3).

- ↑ "Save and Grow farming model launched by FAO". Food and Agriculture Organization.

- ↑ Spitz 1987

- ↑ Robin, Marie-Monique. "The World According to Monsanto". IMDB.

- ↑ http://www.seedsavers.org/site/pdf/HeritageFarmCompanion_BigSix.pdf

- ↑ Shiva, Vandana. Seeds of Suicide. Navdanya.

- ↑ Shiva, V. "Seeds of Suicide". Counter Currents.

- ↑ "Food, Land, Population and the U.S. Economy". Dieoff.com. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Mortality statistics w/references in Wikipedia article on hunger.

- 1 2 3 "Green Revolutionary". Technology Review. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ "World oil supplies are set to run out faster than expected, warn scientists". The Independent. June 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Oil shock could push world food prices higher". CNNMoney. 3 March 2011.

- ↑ "Does a surge in food and oil prices mean that it's now time to panic?". Daily Telegraph. 5 February 2011.

- ↑ Drezé and Sen 1991

- 1 2 Bowbrick, Peter (May 1986). "A Refutation of Professor Sen's Theory of Famine". Food Policy. 11 (2): 105–124. doi:10.1016/0306-9192(86)90059-X.

- ↑ Chapman, Graham P. (2002). "The Green Revolution". The Companion to Development Studies. London: Arnold. pp. 155–9.

- 1 2 Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (2007). Victoria M. Lopez; et al., eds. The Great Riice Robbery: A Handbook on the Impact of IRRI in Asia (PDF). Penang, Malaysia: Pesticide Action Network Asia and the Pacific. ISBN 978-983-9381-35-1. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Conservation Refugees – When Protecting Nature Means Kicking People Out; Dowie, Mark; quote: "...Later that spring, at a Vancouver, British Columbia, meeting of the International Forum on Indigenous Mapping, all two hundred delegates signed a declaration stating that the 'activities of conservation organizations now represent the single biggest threat to the integrity of indigenous lands'..."; November/December 2005; Orion Magazine on line; retrieved March 2014.

- ↑ American Foundations: An Investigative History; Dowie, Mark; 13 April 2001; MIT Press; Massachusetts; (retrieved from Goodreads online); ISBN 0262041898; accessed March 2014.

- ↑ Primary objective was geopolitical – see Dowie, Mark (2001). American Foundations: An Investigative History. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. pp. 109–114.

- ↑ Ross 1998, Ch. 5

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Ponting, Clive (2007). A New Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations. New York: Penguin Books. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-14-303898-6.

- 1 2 Davies, Paul (June 2003). "An Historical Perspective from the Green Revolution to the Gene Revolution". Nutrition Reviews. 61 (6): S124–34. doi:10.1301/nr.2003.jun.S124-S134. PMID 12908744.

- ↑ Shiva, Vandana (March–April 1991). "The Green Revolution in the Punjab". The Ecologist. 21 (2): 57–60.

- ↑ Jennings, Bruce H. (1988). Foundations of international agricultural research: Science and politics in Mexican Agriculture. Boulder: Westview Press. p. 51.

- ↑ "Green Revolution research saved an estimated 18 to 27 million hectares from being brought into agricultural production". Pnas.org. 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- ↑ "'Green Revolution' Brings Greater CO2 Swings". www.climatecentral.org. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- ↑ http://www.resilience.org/stories/2005-04-01/why-our-food-so-dependent-oil

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- 1 2 Loyn, David (26 April 2008). "Punjab suffers from adverse effect of Green revolution". BBC News. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Pimentel, D. (1996). "Green revolution agriculture and chemical hazards". The Science of the Total Environment. 188 (Suppl): S86–S98. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(96)05280-1.

- ↑ Dich J, Zahm SH, Hanberg A, Adami HO (May 1997). "Pesticides and cancer". Cancer Causes Control. 8 (3): 420–43. doi:10.1023/A:1018413522959. PMID 9498903.

- ↑ Zahm, SH; Ward, MH (21 January 2011). "Pesticides and childhood cancer". Environmental Health Perspectives. 106 (Suppl 3): 893–908. doi:10.2307/3434207. PMC 1533072

. PMID 9646054.

. PMID 9646054. - ↑ The Government of Punjab (2004). Human Development Report 2004, Punjab (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 9 August 2011. Section: "The Green Revolution", pp. 17–20.

- 1 2 Sandeep Yadav Faridkot (November 2006). "Green revolution's cancer train". Hardnews. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Green revolution in Punjab, by Vandana Shiva". Livingheritage.org. 15 October 1988. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Garg, Balwant (15 June 2010). "Uranium, metals make Punjab toxic hotspot". The Times of India.

- ↑ "Iowans Who Fed The World - Norman Borlaug: Geneticist". AgBioWorld. 26 October 2002. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Tierney, John (19 May 2008). "Greens and Hunger". TierneyLab – Putting Ideas in Science to the Test. The New York Times. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ↑ "Profits from Poison". Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ Norman Uphoff for SciDevNet 16 October 2013 New approaches are needed for another Green Revolution

- ↑ Tom Chivers for The Daily Telegraph. Last updated: 31 January 2012 The new green revolution that will feed the world,

- ↑ Olivier De Schutter, Gaëtan Vanloqueren. The New Green Revolution: How Twenty-First-Century Science Can Feed the World Solutions 2(4):33–44. Aug 2011

- ↑ FAO Towards a New Green Revolution, in Report from the World Food Summit: Food for All. Rome 13–17 November 1996

References

- Cleaver, Harry (May 1972). "The Contradictions of the Green Revolution". American Economic Review. 62 (2): 177–86.

- Conway, Gordon (1998). The doubly green revolution: food for all in the twenty-first century. Ithaca, N.Y: Comstock Pub. ISBN 0-8014-8610-6.

- Dowie, Mark (2001). American foundations: an investigative history. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT. ISBN 0-262-04189-8.

- Farrell, John Joseph; Altieri, Miguel A. (1995). Agroecology: the science of sustainable agriculture (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview. ISBN 0-8133-1718-5.

- Frison, Emile (2008). "Green Revolution in Africa will depend on biodiversity". Development and Cooperation. 49 (5): 190–3.

- Jain, H.K. (2010). The Green Revolution: History, Impact and Future (1st ed.). Houston, TX: Studium Press. ISBN 1-933699-63-9.

- Oasa, Edmund K (1987). "The Political Economy of International Agricultural Research in Glass". In Glaeser, Bernhard. The Green Revolution revisited: critique and alternatives. Allen & Unwin. pp. 13–55. ISBN 0-04-630014-7.

- Ross, Eric (1998). The Malthus Factor: Poverty, Politics and Population in Capitalist Development. London: Zed Books. ISBN 1-85649-564-7.

- Ruttan, Vernon (1977). "The Green Revolution: Seven Generalizations". International Development Review. 19: 16–23.

- Sen, Amartya Kumar; Drèze, Jean (1989). Hunger and public action. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-828365-2.

- Shiva, Vandana (1989). The violence of the green revolution: Ecological degradation and political conflict in Punjab. Dehra Dun: Research Foundation for Science and Ecology. ISBN 81-85019-19-3.

- Smil, Vaclav (2004). Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-69313-5.

- Spitz, Pierre (1987). "The Green Revolution Re-Examined in India in Glass". In Glaeser, Bernhard. The Green Revolution revisited: critique and alternatives. Allen & Unwin. pp. 57–75. ISBN 0-04-630014-7.

- Wright, Angus (1984). "Innocence Abroad: American Agricultural Research in Mexico". In Bruce Colman; Jackson, Wes; Berry, Wendell. Meeting the expectations of the land: essays in sustainable agriculture and stewardship. San Francisco: North Point Press. pp. 124–38. ISBN 0-86547-171-1.

- Wright, Angus Lindsay (2005). The death of Ramón González: the modern agricultural dilemma. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71268-5.

Further reading

- Cotter, Joseph. Troubled Harvest: Agronomy and Revolution in Mexico, 1880–2002. Westport, CT: Prager, 2003.

- Jain, H.K. (2010). Green revolution: history, impact and future. Houston: Studium Press. ISBN 9781441674487. A brief history, for general readers.

- Harwood, Andrew (14 June 2013). "Development policy and history: lessons from the Green Revolution".

External links

- Norman Borlaug talk transcript, 1996

- The Green Revolution in the Punjab, by Vandana Shiva

- "Accelerating the Green Revolution in Africa". Rockefeller Foundation.

- Moseley, W. G. (14 May 2008). "In search of a better revolution". Minneapolis StarTribune.

- Which Cities are Embracing the Green Revolution? | HouseTrip.com

- Rowlatt, Justin (December 1, 2016). "IR8: The Miracle Rice Which Saved Millions of Lives". BBC News. Retrieved December 1, 2016. About the 50th anniversary of the rice strain.