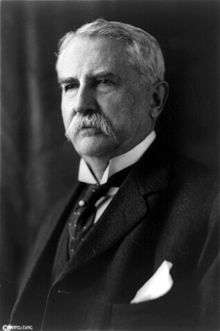

Henry White (diplomat)

Henry White (March 29, 1850 – July 15, 1927) was a prominent U.S. diplomat during the 1890s and 1900s, and one of the signers of the Treaty of Versailles.

Theodore Roosevelt, who was president during the peak of White's career, described White as "the most useful man in the entire diplomatic service, during my Presidency and for many years before." Colonel House, the chief aide to Woodrow Wilson, called White "the most accomplished diplomatist this country has ever produced."

Early life

A native of Baltimore, White was born into a wealthy and socially well-connected Maryland family, the son of John Campbell White and his wife Eliza Ridgely, and the grandson of another Eliza Ridgely (As a boy, White was taken by his grandfather to meet then-President Franklin Pierce). White spent much of his childhood at Hampton, the Maryland estate of his grandparents, today run by the National Park Service.[1]

During the Civil War, the family's sympathies were with the Confederacy. After the war ended in 1865 with a Confederate defeat, White's family moved to France, where White finished his education in Paris. Five years later, war once again set the Whites to flight, moving to England after the fall of Napoleon III during the Franco-Prussian War.

Because White showed signs of ill health after the move to England, he was ordered by his doctor to maintain a vigorous athletic regimen outdoors. These orders led White to become an avid fox hunter; an avocation that in turn allowed him to meet many of the leading figures in Victorian England. He continued to hunt until his marriage, in 1879, to Margaret "Daisy" Stuyvesant Rutherfurd.[2]

Early diplomatic career

White's new wife was an ambitious and hard-working woman who encouraged her husband to pursue the career in diplomacy in which his years in Europe had interested him.

After his marriage, White moved back to the United States after 14 years living overseas. Using the relationships he developed fox hunting, as well as the contacts possessed by his and his wife's families, he expressed his interest in getting a diplomatic post.

After three years of networking, White's efforts were rewarded in the summer of 1883 with the secretaryship of the U.S. legation in Vienna, working under minister Alphonso Taft. At the end of the year, he was promoted to be second secretary of the far more important U.S. legation in London, working under minister James Russell Lowell; a post he kept even after a Democratic victory in the 1884 presidential election led to Lowell, like White a Republican appointee, being turned out of office in 1885. White was even promoted, to first secretary of the legation, in 1886. After seven years in that post, under ministers Edward J. Phelps, Robert T. Lincoln, and Thomas F. Bayard, White was removed from office for political reasons in October 1893.

American interlude

After stepping down in London, White and his family returned to the United States, a country which White had lived in for only three of the past 27 years. The family moved to Washington, D.C., where White laid the groundwork for a return to the diplomatic service.

Throughout White's diplomatic career, his prospects were helped by the social grace of himself and his wife. As a bachelor, White had ingratiated himself with the British sporting set. As a married couple, Henry and Margaret White had been popular with British intellectuals, and were charter members of The Souls.

The Whites now made themselves welcome in salons throughout Washington, making or renewing friendships with Theodore Roosevelt, John Hay, Chauncey Depew, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Levi P. Morton, among many others. These relationships White had formed with both British and American leaders were what made him an invaluable diplomat. White was able to serve as an unusually effective intermediary between the British and American governments because he was known and trusted by both sides. During the years when White was active in the United Kingdom, both the British and the American governments wanted close relations with the other, so White was able to use his ability to mediate with greatest effect.

Back in the diplomatic service

William McKinley's election to the presidency in 1896 brought White back into a government post. McKinley offered White the position of U.S. minister to Spain, but White chose to return to his old position as first secretary at the London embassy, where Hay was now the ambassador (the U.S. diplomatic mission in London had been upgraded from a legation to an embassy in 1895).

When Hay was recalled to Washington in 1898 for a promotion to Secretary of State, White had hoped to become ambassador, but that position went to Joseph H. Choate instead. As acting chargé d'affaires while awaiting Choate's arrival, White played a key role in the negotiations leading to the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty.

In 1899, Margaret White was struck down by a degenerative nerve disease. She would recover only partially, and spent much of her time away at resorts, conserving her strength. For the next 10 years, the Whites' daughter Muriel would fill in as hostess during her mother's absences.

Ambassadorial years

On March 6, 1905, White received his long-awaited promotion to Ambassador, as President Roosevelt named him to represent the United States with Italy.

While Ambassador to Italy, White served as the lead U.S. mediator during the 1906 Algeciras Conference. The agreement reached during that conference averted a war between France and Germany over economic rights in Morocco.

On December 19, 1906, White received another promotion from Roosevelt, this time to be the U.S. ambassador to France, replacing Robert Sanderson McCormick who retired due to his health.[3] He stayed in that position until President Taft took office in 1909 and requested his resignation.

Semi-retirement

White remained active in U.S. diplomacy after leaving Paris. He accompanied Roosevelt on the now-former President's tour of Europe in 1910, serving as Roosevelt's de facto chief of staff during visits to Paris and Berlin and during Roosevelt's service as the U.S. special representative to the funeral of King Edward VII. During the trip, Roosevelt and White met with every major chief of state in Europe except Tsar Nicholas II.

In 1910, White also accepted an assignment from Taft to head the U.S. delegation to the Pan-American Conference in Buenos Aires. As a result of his discussions with Latin American diplomats, White wrote a strong recommendation to Secretary of State Philander C. Knox that these diplomats be treated with more respect and tact. White became an active member of the Pan-American Society after returning from Buenos Aires.

In between diplomatic missions, White supervised the construction of a new mansion in Washington, D.C., designed by John Russell Pope. Later known as the White-Meyer House, it is today part of the Meridian International Center.[4] The house, located off 16th Street, was near many of the city's foreign embassies, and White actively socialized with ambassadors from around the world.

World War I

White's daughter had married Graf (Ernst Hans Christoph Roger) Hermann von Seherr-Thoss,[5] a German aristocrat, in 1909, and White was in Germany visiting them when World War I started in 1914. He and his wife were sequestered in Berlin for two weeks, and then were able to leave for home via the Netherlands with their daughter's two children, who spent the first two years of the war in the United States.

Because White had strong ties to both England and Germany, he remained neutral in his sympathies during the early years of the war, an attitude which gradually made him a supporter of President Woodrow Wilson, who also advocated neutrality and peace.

In 1914, the Wilson administration asked White first to head the American delegation to the 1914 Pan-American Conference and later to serve as Minister to Haiti. White declined both offers, though, and stayed out of diplomacy during these years because of the rapidly declining health of his wife, who died on September 2, 1916.

When Germany declared that it would conduct unrestricted submarine warfare against U.S. ships, White realized that U.S. entry into the war was inevitable, and he supported it wholeheartedly. When the French sent a special military mission, headed by Marshal Joffre, to the United States after the declaration of war, White hosted the mission in his mansion.

American Peace Commissioner

On November 19, 1918, shortly after the declaration of the Armistice, White received a surprise invitation from President Wilson to serve as one of the five American Peace Commissioners, who would go to France to work on the peace treaty with Germany. Wilson extended the invitation because White was a Republican yet still a supporter of Wilson's peace aims. Wilson also valued White as being the most experienced American diplomat of the time, and a man who knew most of the European leaders with whom the Commission would deal.

The Commission arrived in Paris on December 14. White talked with dignitaries from across Europe to learn what various groups wanted and what they would accept. He also sought unsuccessfully to find a common ground between Wilson and the Senate Republicans (led by Lodge) who would be in a position to reject the treaty Wilson was negotiating.

After the peace treaty with Germany was signed (the U.S. Senate later refused to ratify it), Wilson and Secretary of State Robert Lansing returned to the United States, leaving White to lead the delegation in drafting the peace treaties with Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria until he could be relieved of command by the Assistant Secretary of State. After five more months of work, White and the remainder of the delegation left Paris on December 9, 1919.

Upon his return to the United States, White continued to try to bring Wilson and Lodge together to compromise and get the treaty approved by the Senate. On March 19, 1920, however, the Senate rejected the treaty.

Retirement

The rejection of the treaty ended White's diplomatic career, though he continued to be active in public life, as a trustee for the National Geographic Society, the Corcoran Gallery, and the Smithsonian Institution, among other organizations. White also continued to correspond and host friends from the diplomatic and political worlds.

On November 3, 1920, White remarried, to Emily Vanderbilt Sloane.

In 1926, White's health began to fail, and he spent much of his time confined to bed. He died a few hours after undergoing an operation.

White's body was buried in the National Cathedral in Washington D.C., near the tomb of Woodrow Wilson.

Children

Henry and Margaret White had two children:

- Muriel White (October 12, 1880 – March 13, 1943). She married Count (Ernst Hans Christoph Roger) Hermann Seherr-Thoss, a Prussian aristocrat, in Paris on April 28, 1909, and lived in Germany for the rest of her life.

- John Campbell White (March 1884 – June 11, 1967). He married Elizabeth Moffat. He served in the U.S. Foreign Service as a diplomat from 1914 to 1945, and was U.S. ambassador to Haiti (1941–1944) and Peru (1944–1945).

Trivia

- White was a member of the Knickerbocker Club from 1876 until his death.

References

- ↑ Ridgely bios from Hampton National Historic Site website

- ↑ She was the daughter of astronomer Lewis Morris Rutherfurd and his wife, Margaret Stuyvesant Chanler, the sister of John Winthrop Chanler, U.S. Representative from New York, (and a descendant of Peter Stuyvesant).

- ↑ "R.S. M'CORMICK, EX-DIPLOMAT, DIES; Father of Illinois Senator and of Chicago Tribune Editor a Pneumonia Victim". The New York Times. April 17, 1919. p. 11. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ↑ History of the property from the Meridian International Center website

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Gräfliche Häuser, von Hueck, Walter, C. A. Starke Verlag, Limburg an der Lahn, 1991, p. 324.

- "John C. White, 83, A Career Diplomat." New York Times. 12 Jun 1967: 45.

- "Henry White, Noted Diplomat, 77, Dead." New York Times. 16 Jul 1927.

- Nevins, Allan (1930). Henry White: Thirty Years of American Diplomacy. New York: Harper & Brothers.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry White (diplomat). |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article about Henry White. |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Robert S. McCormick |

U.S. Ambassador to France 1906–1909 |

Succeeded by Robert Bacon |