Ketogenesis

Ketogenesis is the biochemical process by which organisms produce a group of substances collectively known as ketone bodies by the breakdown of fatty acids and ketogenic amino acids.[1][2] This process supplies energy to certain organs (particularly the brain) under circumstances such as fasting, but insufficient ketogenesis can cause hypoglycemia and excessive production of ketone bodies leads to a dangerous state known as ketoacidosis.[3]

Production

Ketone bodies are produced mainly in the mitochondria of liver cells, and synthesis can occur in response to an unavailability of blood glucose, such as during fasting.[3]

Ketogenesis takes place in the setting of low glucose levels in the blood, after exhaustion of other cellular carbohydrate stores, such as glycogen. It can also take place when there is insufficient insulin (e.g. in diabetes), particularly during periods of "ketogenic stress" such as intercurrent illness.[3]

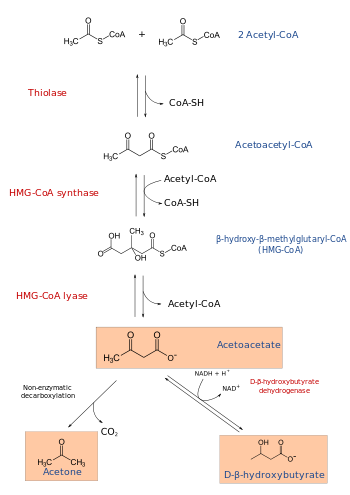

The production of ketone bodies is then initiated to make available energy that is stored as fatty acids. Fatty acids are enzymatically broken down in β-oxidation to form acetyl-CoA. Under normal conditions, acetyl-CoA is further oxidized by the citric acid cycle (TCA/Krebs cycle) and then by the mitochondrial electron transport chain to release energy. However, if the amounts of acetyl-CoA generated in fatty-acid β-oxidation challenge the processing capacity of the TCA cycle; i.e. if activity in TCA cycle is low due to low amounts of intermediates such as oxaloacetate, acetyl-CoA is then used instead in biosynthesis of ketone bodies via acetoacyl-CoA and β-hydroxy-β-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA). Deaminated amino acids that are ketogenic, such as leucine, also feed TCA cycle, forming acetoacetate & ACoA and thereby produce ketones.[1] Besides its role in the synthesis of ketone bodies, HMG-CoA is also an intermediate in the synthesis of cholesterol, but the steps are compartmentalised.[1][2] Ketogenesis occurs in the mitochondria, whereas cholesterol synthesis occurs in the cytosol, hence both the processes are independently regulated.[2]

Ketone bodies

The three ketone bodies, each synthesized from acetyl-CoA molecules, are:

- Acetoacetate, which can be converted by the liver into β-hydroxybutyrate, or spontaneously turn into acetone

- Acetone, which is generated through the decarboxylation of acetoacetate, either spontaneously or through the enzyme acetoacetate decarboxylase. It can then be further metabolized either by CYP2E1 into hydroxyacetone (acetol) and then via propylene glycol to pyruvate, lactate and acetate (usable for energy) and propionaldehyde, or via methylglyoxal to pyruvate and lactate.[4][5][6]

- β-hydroxybutyrate (not technically a ketone according to IUPAC nomenclature) is generated through the action of the enzyme D-β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase on acetoacetate.

Regulation

Ketogenesis may or may not occur, depending on levels of available carbohydrates in the cell or body. This is closely related to the paths of acetyl-CoA:

- When the body has ample carbohydrates available as energy source, glucose is completely oxidized to CO2; acetyl-CoA is formed as an intermediate in this process, first entering the citric acid cycle followed by complete conversion of its chemical energy to ATP in oxidative phosphorylation.

- When the body has excess carbohydrates available, some glucose is fully metabolized, and some of it is stored in the form of glycogen or, upon citrate excess, as fatty acids. (CoA is also recycled here.)

- When the body has no free carbohydrates available, fat must be broken down into acetyl-CoA in order to get energy. Acetyl-CoA is not being recycled through the citric acid cycle because the citric acid cycle intermediates (mainly oxaloacetate) have been depleted to feed the gluconeogenesis pathway, and the resulting accumulation of acetyl-CoA activates ketogenesis.

Pathology

Both acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate are acidic, and, if levels of these ketone bodies are too high, the pH of the blood drops, resulting in ketoacidosis. Ketoacidosis is known to occur in untreated type I diabetes (see diabetic ketoacidosis) and in alcoholics after prolonged binge-drinking without intake of sufficient carbohydrates (see alcoholic ketoacidosis).

Ketogenesis can be ineffective in people with beta oxidation defects.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Kohlmeier M (2015). "Leucine". Nutrient Metabolism: Structures, Functions, and Genes (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 385–388. ISBN 9780123877840. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

Figure 8.57: Metabolism of L-leucine

- 1 2 3 Kohlmeier M (2015). "Fatty acids". Nutrient Metabolism: Structures, Functions, and Genes (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 9780123877840. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Fukao, Toshiyuki; Mitchell, Grant; Sass, Jörn Oliver; Hori, Tomohiro; Orii, Kenji; Aoyama, Yuka (8 April 2014). "Ketone body metabolism and its defects". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 37 (4): 541–551. doi:10.1007/s10545-014-9704-9. PMID 24706027.

- ↑ Glew, Robert H. "You Can Get There From Here: Acetone, Anionic Ketones and Even-Carbon Fatty Acids can Provide Substrates for Gluconeogenesis". Retrieved August 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Miller DN, Bazzano G; Bazzano (1965). "Propanediol metabolism and its relation to lactic acid metabolism". Ann NY Acad Sci. 119 (3): 957–973. Bibcode:1965NYASA.119..957M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb47455.x. PMID 4285478.

- ↑ Ruddick JA (1972). "Toxicology, metabolism, and biochemistry of 1,2-propanediol". Toxicol App Pharmacol. 21: 102–111. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(72)90032-4.

External links

- Fat metabolism at University of South Australia

- James Baggott. (1998) Synthesis and Utilization of Ketone Bodies at University of Utah Retrieved 23 May 2005.

- Musa-Veloso K, Likhodii SS, Cunnane SC (1 July 2002). "Breath acetone is a reliable indicator of ketosis in adults consuming ketogenic meals". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 76 (1): 65–70. PMID 12081817.

- Richard A. Paselk. (2001) Fat Metabolism 2: Ketone Bodies at Humboldt State University Retrieved 23 May 2005.

.svg.png)