Kingdom of Yugoslavia

| Kingdom of Yugoslaviaa | ||||||||||||

| Kraljevina Jugoslavija Краљевина Југославија | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Motto "Jedan narod, jedan kralj, jedna država" (Latin) Један народ, један краљ, једна држава (Cyrillic) "One people, one king, one country" | ||||||||||||

| Anthem National Anthem of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia | ||||||||||||

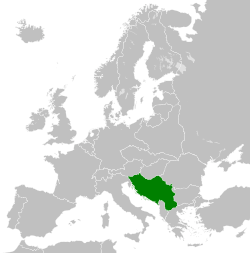

Location and extent of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Europe during the 1930s | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Belgrade | |||||||||||

| Languages | Official language: Serbo-Croato-Slovene[1]b | |||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy (1918–1929, 1934–1945) Absolute monarchy (1929–1934) | |||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||

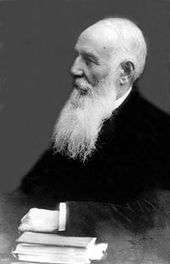

| • | 1918–1921 | Peter I | ||||||||||

| • | 1921–1934 | Alexander I | ||||||||||

| • | 1934–1945 | Peter IIc | ||||||||||

| Prince Regent | ||||||||||||

| • | 1918–1921 | Prince Alexander | ||||||||||

| • | 1934–1941 | Prince Paul | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||||

| • | 1918–1919 (first) | Stojan Protić | ||||||||||

| • | 1945 (last) | Josip Broz Tito | ||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||||||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||||||||

| • | Lower house | Chamber of Deputies | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period · World War II | |||||||||||

| • | Creation | 1 December 1918 | ||||||||||

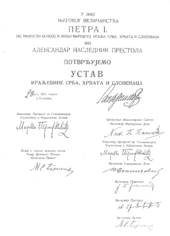

| • | Vidovdan Constitution | 28 June 1921 | ||||||||||

| • | Dictatorship | 6 January 1929 | ||||||||||

| • | Axis invasion | 6 April 1941 | ||||||||||

| • | Democratic Federative Yugoslavia | 4 December 1943 | ||||||||||

| • | Treaty of Vis | 2 November 1945 | ||||||||||

| • | Abolition of monarchy | 29 November 1945 | ||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||

| • | 1918 | 247,542 km² (95,577 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||

| • | 1918 est. | 12,017,323 | ||||||||||

| Density | 48.5 /km² (125.7 /sq mi) | |||||||||||

| • | 1931 est. | 13,934,038 | ||||||||||

| Density | 56.3 /km² (145.8 /sq mi) | |||||||||||

| Currency | Yugoslav krone (1918–1920) Royal Yugoslav dinar (1920–1945) | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||

| a. | Previously called the "Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes" (1918–1929). | |||||||||||

| b. | Declared in both of the country's constitutions (1921 and 1931), srpsko-hrvatsko-slovenački is also translated as Serbo-Croato-Slovene or Serbocroatoslovenian, despite Serbo-Croat and Slovene being separate languages.[2][3] | |||||||||||

| c. | Peter II, still underage, was brought to power by a military coup. Shortly after his accession, Yugoslavia was occupied by the Axis and the young King went into exile. In 1944, he accepted the formation of Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, along with a temporary vacancy in the position of head of state. He was formally deposed by the Yugoslav parliament in 1945. | |||||||||||

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia (Serbo-Croatian: Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Serbian Cyrillic: Краљевина Југославија, "Kingdom of South Slavia)[4] was a state in Southeast Europe and Central Europe, that existed during the interwar period (1918–1939) and first half of World War II (1939–1943). It was formed in 1918 by the merger of the provisional State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (itself formed from territories of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire) with the formerly independent Kingdom of Serbia. The Kingdom of Montenegro had united with Serbia five days previously, while the regions of Kosovo, Vojvodina and Vardar Macedonia were parts of Serbia prior to the unification. For its first eleven years of existence, the Kingdom was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" was its colloquial name from its origins.[5] The official name of the state was changed to "Kingdom of Yugoslavia" by King Alexander I on 3 October 1929.[5]

The state was ruled by the Serbian dynasty of Karađorđević, which previously ruled the Kingdom of Serbia under Peter I from 1903 (after the May Overthrow) onwards. Peter I became the first king of Yugoslavia until his death in 1921. He was succeeded by his son Alexander I, who had been regent for his father. He was known as "Alexander the Unifier" and he renamed the kingdom "Yugoslavia" in 1929. He was assassinated in Marseille by Vlado Chernozemski, a member of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), during his visit to France in 1934. The crown passed to his then-still under-aged son Peter. His cousin Paul ruled as Prince regent until 1941, when Peter II would come of age.[6] The royal family flew to London the same year, prior to the country being invaded by the Axis powers.

In April 1941, the country was occupied and partitioned by the Axis powers. A royal government-in-exile, recognized by the United Kingdom and, later, by all the Allied powers, was established in London. In 1944, after pressure from the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the King recognized the government of Democratic Federal Yugoslavia as the legitimate government. This was established on 2 November following the signing of the Treaty of Vis by Ivan Šubašić (on behalf of the Kingdom) and Josip Broz Tito (on behalf of the Yugoslav Partisans).[7]

Formation

Following the assassination of Austrian Archduke Francis Ferdinand by the Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip, the subsequent invasion of Serbia, and the outbreak of World War I, South Slavic nationalism escalated and Slavic nationalists called for the independence and unification of the South Slavic nationalities of Austria-Hungary along with Serbia and Montenegro into a single State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.

The Dalmatian Croat politician Ante Trumbić became a prominent South Slavic leader during the war and led the Yugoslav Committee that lobbied the Allies to support the creation of an independent Yugoslavia.[8] Trumbić faced initial hostility from Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić, who preferred an enlarged Serbia over a unified Yugoslav state. However, both Pašić and Trumbić agreed to a compromise, which was delivered at the Corfu Declaration on 20 July 1917 that advocated the creation of a united state of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes to be led by the Serbian House of Karađorđević.[8]

In 1916, the Serbian Parliament in exile decided on the creation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia at a meeting inside the Municipal Theatre of Corfu.[9] The Kingdom was formed on 1 December 1918 under the name "Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes" (Serbian: Краљевина Срба, Хрвата и Словенаца Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, Croatian: Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, Slovene: Kraljevina Srbov, Hrvatov in Slovencev) or its abbreviated form "Kingdom of SHS" (Краљевина СХС Kraljevina SHS).

On 1 December 1918, the new kingdom was proclaimed by Alexander Karađorđević, Prince-Regent for his father, Peter I of Serbia. The new kingdom was made up of the formerly independent kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro (Montenegro having been absorbed into Serbia the previous month), and of a substantial amount of territory that was formerly part of Austria–Hungary, the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. The lands previously in Austria–Hungary that formed the new state included:

- Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia and Vojvodina from the Hungarian part of the empire,

- Carniola, part of Styria, and most of Kingdom of Dalmatia from the Austrian part, and

- The Austria–Hungarian condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The creation of the state was supported by pan-Slavists and Serbian nationalists. For the pan-Slavic movement, all of the South Slav (Yugoslav) people had united into a single state. For Serbian nationalists, the desired goal of uniting the majority of the Serb population across south-eastern Europe into one state was also achieved. Furthermore, as Serbia already had a government, military, and police force, it was the logical choice to form the nucleus of the Yugoslav state.

The newly established Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes participated in the Paris Peace Conference with Trumbić as the country's representative.[8] Since the Allies had lured the Italians into the war with a promise of substantial territorial gains in exchange, which cut off a quarter of Slovene ethnic territory from the remaining three quarters of Slovenes living in the Kingdom of SHS, Trumbić successfully vouched for the inclusion of most Slavs living in the former Austria-Hungary to be included within the borders of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, nevertheless with the Treaty of Rapallo[8] a population of half a million Slavs,[10] mostly Slovenes, were subjected to forced Italianization until the fall of Fascism in Italy. At the time when Benito Mussolini was willing to modify the Rapallo borders in order to annex the independent state of Rijeka to Italy, Pašić's attempts to correct the borders at Postojna and Idrija were effectively undermined by the regent Alexander who preferred "good relations" with Italy.[11]

The Yugoslav kingdom bordered Italy and Austria to the northwest at the Rapallo border, Hungary and Romania to the north, Bulgaria to the east, Greece and Albania to the south, and the Adriatic Sea to the west. Almost immediately, it ran into disputes with most of its neighbours. Slovenia was difficult to determine, since it had been an integral part of Austria for 400 years. The Vojvodina region was disputed with Hungary, Macedonia with Bulgaria, Fiume with Italy.

A plebiscite was also held in the Province of Carinthia, which opted to remain in Austria. Austrians had formed a majority in this region although numbers reflected that some Slovenes did vote for Carinthia to become part of Austria. The Dalmatian port city of Zadar (Italian: Zara) and a few of the Dalmatian islands were given to Italy. The city of Rijeka (Italian: Fiume) was declared to be the Free State of Fiume, but it was soon occupied, and in 1924 annexed, by Italy, which had also been promised the Dalmatian coast during World War I, and Yugoslavia claiming Istria, a part of the former Austrian Littoral which had been annexed to Italy, but which contained a considerable population of Croats and Slovenes.

The formation of the constitution of 1921 sparked tensions between the different Yugoslav nationalities.[8] Trumbić opposed the 1921 constitution and over time grew increasingly hostile towards the Yugoslav government that he saw as being centralized in the favour of Serb hegemony over Yugoslavia.[8]

Economy

Farming

Three quarters of the Yugoslav workforce was engaged in agriculture. A few commercial farmers existed, but most were subsistence peasants. Those in the south were especially poor, living in a hilly, infertile region. No large estates existed except in the north, and all of those were owned by foreigners. Indeed, one of the first actions undertaken by the new Yugoslav state in 1919 was to break up the estates and dispose of foreign, and in particular Magyar landowners. Nearly 40% of the rural population was surplus (i.e., excess people not needed to maintain current production levels), and despite a warm climate, Yugoslavia was also relatively dry. Internal communications were poor, damage from World War I had been extensive, and with few exceptions agriculture was devoid of machinery or other modern farming technologies.

Manufacturing

Manufacturing was limited to Belgrade and the other major population centers, and consisted mainly of small, comparatively primitive facilities that produced strictly for the domestic market. The commercial potential of Yugoslavia's Adriatic ports went to waste because the nation lacked the capital or technical knowledge to operate a shipping industry. On the other hand, the mining industry was well developed due to the nation's abundance of mineral resources, but since it was primarily owned and operated by foreigners, most production was exported. Yugoslavia on the whole was the third least industrialized nation in Eastern Europe after Bulgaria and Albania.

Debt

Yugoslavia was typical of Eastern European nations in that it borrowed large sums of money from the West during the 1920s. When the Great Depression began in 1930, the Western lenders called in their debts, which could not be paid back. Some of the money was lost to graft, although most was used by farmers to improve production and export potential. Agricultural exports were always an unstable prospect, and the Depression caused the market for them to collapse as nations everywhere erected trade barriers. Italy was a major trading partner of Yugoslavia in the initial years after World War I, but ties fell off after Benito Mussolini came to power. In the grim economic situation of the 1930s, Yugoslavia followed the lead of its neighbors in allowing itself to become a dependent of Nazi Germany.

Ethnic groups

The small middle class occupied the major population centers and almost everyone else were peasants engaged in subsistence agriculture. The largest ethnic group were Serbs followed by Croats, Slovenes, Bosnian Muslims, Macedonians and Albanians. Religion followed the same pattern with half the population following Orthodox Christianity, 40 or so percent being Catholic, and the rest Muslim. In such a polyglot nation, tensions were frequent, but especially between Serbs and Croats. Other quarrels were those between Serbs and Macedonians, as the Yugoslav government had as its official position that the latter were ethnic Serbs. In the early 20th century the international community viewed the Macedonians predominantly as regional variety of Bulgarians, but during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the Allies sanctioned the Serbian control of Vardar Macedonia and its view, that Macedonian Slavs were in fact Southern Serbs.[12]

Slovenes were closer to Croats in terms of religion and culture. In particular, the Slovenes knew they were too small in numbers to form a nation of their own and there was no reason to suppose a Croat-dominated Yugoslavia would be any better or worse than a Serb-dominated one. For the most part, they went along with the general political flow and were not a significant source of problems.

The predominantly Muslim Bosniaks won some concessions from Belgrade, but always faced strong dislike from their neighbors, especially Serbs and were known to one and all as "Turks" regardless of their Slavic ethnicity. Albanians fared worse since they did not speak Serbo-Croatian, but all Muslims were the subject of widespread prejudice in Yugoslavia. Some regions of the country were allowed to exist as enclaves of Islamic law regarding personal status, which was a concession made to the Muslim population of Yugoslavia.[13]

Other lesser minorities included Italians, Romanians, Germans, Magyars and Greeks. Aside from the Romanians, the Yugoslav government awarded no special treatment to them in terms of respect for their language, culture, or political autonomy, not surprising given that all of their native countries had territorial disputes with Yugoslavia. A few Jews lived in the major cities; they were well-assimilated and there were no significant problems with anti-Semitism.

Education

Although Yugoslavia had compulsory public schooling, it was inaccessible to most peasants. Official literacy figures for the population stood at 50%, but it varied widely throughout the country. Less than 10% of Slovenes were illiterate, but a staggering 80% of Macedonians and Bosnians could not read or write. Only 10% of elementary school students went on to high school, but for those that did, they had access to three universities in Belgrade, Ljubljana, and Zagreb.

Political history

Early politics

Immediately after the 1 December proclamation, negotiations between the National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and the Serbian government resulted in agreement over the new government which was to be headed by Nikola Pašić. However, when this agreement was submitted to the approval of the regent, Alexander Karađorđević, it was rejected, producing the new state's first governmental crisis. Many regarded this rejection as a violation of parliamentary principles, but the matter was resolved when the regent suggested replacing Pašić with Stojan Protić, a leading member of Pašić's Radical Party. The National Council and the Serbian government agreed and the new government came into existence on 20 December 1918.[14][15]

In this period before the election of the Constituent Assembly, a Provisional Representation served as a parliament which was formed by delegates from the various elected bodies that had existed before the creation of the state. A realignment of parties combining several members of the Serbian opposition with political parties from the former Austria–Hungary led to the creation of a new party, The Democratic Party, that dominated the Provisional Representation and the government.

Because the Democratic Party led by Ljubomir Davidović pushed a highly centralized agenda a number of Croatian delegates moved into opposition. However, the radicals themselves were not happy that they had only three ministers to the Democratic Party's 11 and, on 16 August 1919, Protić handed in his resignation. Davidović then formed a coalition with the Social Democrats. This government had a majority, but the quorum of the Provisional Representation was half plus one vote. The opposition then began to boycott the parliament. As the government could never guarantee that all of its supporters would turn up, it became impossible to hold a quorate meeting of the parliament. Davidović soon resigned, but as no one else could form a government he again became prime minister. As the opposition continued their boycott, the government decided it had no alternative but to rule by decree. This was denounced by the opposition who began to style themselves as the Parliamentary Community. Davidović realized that the situation was untenable and asked the King to hold immediate elections for the Constituent Assembly. When the King refused, he felt he had no alternative but to resign.

The Parliamentary Community now formed a government led by Stojan Protić committed to the restoration of parliamentary norms and mitigating the centralization of the previous government. Their opposition to the former governments program of radical land reform also united them. As several small groups and individuals switched sides, Protić now even had a small majority. However, the Democratic Party and the Social Democrats now boycotted parliament and Protić was unable to muster a quorum. Hence the Parliamentary Community, now in government, was forced to rule by decree.

For the Parliamentary Community to thus violate the basic principle around which they had formed put them in an extremely difficult position. In April 1920, widespread worker unrest and a railway strike broke out. According to Gligorijević, this put pressure on the two main parties to settle their differences. After successful negotiations, Protić resigned to make way for a new government led by the neutral figure of Milenko Vesnić. The Social Democrats did not follow the Democratic Party, their former allies, into government because they were opposed to the anti-communist measures to which the new government was committed.

The controversies that had divided the parties earlier were still very much live issues. The Democratic Party continued to push its agenda of centralization and still insisted on the need for radical land reform. A disagreement over electoral law finally led the Democratic Party to vote against the government in Parliament and the government was defeated. Though this meeting had not been quorate, Vesnić used this as a pretext to resign. His resignation had the intended effect: the Radical Party agreed to accept the need for centralization, and the Democratic Party agreed to drop its insistence on land reform. Vesnić again headed the new government. The Croatian Community and the Slovenian People's Party were however not happy with the Radicals' acceptance of centralization. Neither was Stojan Protić, and he withdrew from the government on this issue.

In September 1920 a peasant revolt broke out in Croatia, the immediate cause of which was the branding of the peasants' cattle. The Croatian community blamed the centralizing policies of the government and of minister Svetozar Pribićević in particular.

Constituent assembly to dictatorship

One of the few laws successfully passed by the Provisional Representation was the electoral law for the constituent assembly. During the negotiations that preceded the foundation of the new state, it had been agreed that voting would be secret and based on universal suffrage. It had not occurred to them that universal might include women until the beginning of a movement for women's suffrage appeared with the creation of the new state. The Social Democrats and the Slovenian People's Party supported women's suffrage but the Radicals opposed it. The Democratic Party was open to the idea but not committed enough to make an issue of it so the proposal fell. Proportional Representation was accepted in principle but the system chosen (d'Hondt with very small constituencies) favored large parties and parties with strong regional support.

The election was held on 28 November 1920. When the votes were counted the Democratic Party had won the most seats, more than the Radicals — but only just. For a party that had been so dominant in the Provisional Representation, that amounted to a defeat. Further it had done rather badly in all former Austria-Hungarian areas. That undercut the party's belief that its centralization policy represented the will of the Yugoslavian people as a whole. The Radicals had done no better in that region but this presented them far less of a problem because they had campaigned openly as a Serbian party. The most dramatic gains had been made by the two anti-system parties. The Croatian Republican Peasant Party's leadership had been released from prison only as the election campaign began to get underway. According to Gligorijević, this had helped them more than active campaigning. The Croatian community (that had in a timid way tried to express the discontent that Croatian Republican Peasant Party mobilized) had been too tainted by their participation in government and was all but eliminated. The other gainers were the communists who had done especially well in the wider Macedonia region. The remainder of the seats were taken up by smaller parties that were at best skeptical of the centralizing platform of the Democratic Party.

The results left Nikola Pašić in a very strong position as the Democrats had no choice but to ally with the Radicals if they wanted to get their concept of a centralized Yugoslavia through. Pašić was always careful to keep open the option of a deal with the Croatian opposition. The Democrats and the Radicals were not quite strong enough to get the constitution through on their own and they made an alliance with the Yugoslav Muslim Organization (JMO). The Muslim party sought and got concessions over the preservation of Bosnia in its borders and how the land reform would affect Muslim landowners in Bosnia.

The Croatian Republican Peasant Party refused to swear allegiance to the King on the grounds that this presumed that Yugoslavia would be a monarchy, something that it contended only the Constituent Assembly could decide. The party was unable to take its seats. Most of the opposition though initially taking their seats declared boycotts as time went so that there were few votes against. However, the constitution decided against 1918 agreement between the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and the Kingdom of Serbia, which stated that a 66% majority that 50% plus one vote would be needed to pass, irrespective of how many voted against. Only last minute concessions to Džemijet – a group of Muslims from Macedonia and Kosovo – saved it.

On 28 June 1921, the Vidovdan (St Vitus's Day) Constitution was passed, establishing a unitary monarchy. The pre–World War I traditional regions were abolished and 33 new administrative oblasts (provinces) ruled from the center were instituted. During this time, King Peter I died (16 August 1921), and the prince-regent succeeded to the throne as King Alexander I.

Ljubomir Davidović of the Democrats began to have doubts about the wisdom of his party's commitment to centralization and opened up negotiations with the opposition. This threatened to provoke a split in his party as his action was opposed Svetozar Pribićević. It also gave Pašić a pretext to end the coalition. At first the King gave Pašić a mandate to form a coalition with Pribićević's Democrats. However, Pašić offered Pribićević too little for there to be much chance that Pribićević would agree. A purely Radical government was formed with a mandate to hold elections. The Radicals made gains at the expense of the Democrats but elsewhere there were gains by Radić's Peasant's Party.

Serb politicians around Radic regarded Serbia as the standard bearer of Yugoslav unity, as the state of Piedmont had been for Italy, or Prussia for the German Empire; a kind of "Greater Serbia". Over the following years, Croatian resistance against a Serbo-centric policy increased.

In the early 1920s, the Yugoslav government of prime minister Nikola Pašić used police pressure over voters and ethnic minorities, confiscation of opposition pamphlets[16] and other measure to rig elections. This was ineffective against the Croatian Peasant Party (formerly the Croatian Republican Peasant Party), whose members continued to win election to the Yugoslav parliament in large numbers,[17] but did harm the Radicals' main Serbian rivals, the Democrats.

Stjepan Radić, the head of the Croatian Peasant Party, was imprisoned many times for political reasons.[18] He was released in 1925 and returned to parliament.

In the spring of 1928, Radić and Svetozar Pribićević waged a bitter parliamentary battle against the ratification of the Nettuno Convention with Italy. In this they mobilised nationalist opposition in Serbia but provoked a violent reaction from the governing majority including death threats. On 20 June 1928, a member of the government majority, the Serb deputy Puniša Račić, shot five members of the Croatian Peasant Party, including their leader Stjepan Radić. Two died on the floor of the Assembly while the life of Radić hung in the balance.

The opposition now completely withdrew from parliament, declaring that they would not return to a parliament in which several of their representatives had been killed, and insisting on new elections. On 1 August, at a meeting in Zagreb, they renounced 1 December Declaration of 1920. They demanded that the negotiations for unification should begin from scratch. On 8 August Stjepan Radić died.

6 January dictatorship

On 6 January 1929, using as a pretext the political crisis triggered by the shooting, King Alexander abolished the Constitution, prorogued the Parliament and introduced a personal dictatorship (known as the "January 6 Dictatorship", Šestosiječanjska diktatura, Šestojanuarska diktatura). He changed the name of the country to "Kingdom of Yugoslavia", and changed the internal divisions from the 33 oblasts to nine new banovinas on 3 October. A Court for the Protection of the State was soon established to act as the new regime's tool for putting down any dissent. Opposition politicians Vladko Maček and Svetozar Pribićević were arrested under charges by the court. Pribićević later went into exile, while over the course of the 1930s, Maček would become the leader of the entire opposition bloc.

Immediately after the dictatorship was proclaimed, Croatian deputy Ante Pavelić left for exile from the country. The following years Pavelić worked to establish a revolutionary organization, the Ustaše, allied with the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) against the state.

In 1931, Alexander decreed a new Constitution which made executive power the gift of the King. Elections were to be by universal male suffrage. The provision for a secret ballot was dropped, and pressure on public employees to vote for the governing party was to be a feature of all elections held under Alexander's constitution. Further, half the upper house was directly appointed by the King, and legislation could become law with the approval of one of the houses alone if also approved by the King.

That same year, Croatian historian and anti-Yugoslavist intellectual[19] Milan Šufflay was assassinated in Zagreb. As a response, Albert Einstein and Heinrich Mann sent an appeal to the International League of Human Rights in Paris condemning the murder, accusing the Yugoslav government. The letter states of a "horrible brutality which is being practiced upon the Croatian People." The appeal was addressed to the Paris-based Ligue des droits de l'homme[20] (Human Rights League).[21] In their letter Einstein and Mann held the Yugoslav king Aleksandar explicitly responsible for these circumstances.[21][22][23]

Croat opposition to the new régime was strong and, in late 1932, the Croatian Peasant Party issued the Zagreb Manifesto which sought an end to Serb hegemony and dictatorship. The government reacted by imprisoning many political opponents including the new Croatian Peasant Party leader Vladko Maček. Despite these measures, opposition to the dictatorship continued, with Croats calling for a solution to what was called the "Croatian question". In late 1934, the King planned to release Maček from prison, introduce democratic reforms, and attempt find common ground between Serbs and Croats.

However, on 9 October 1934, the king was assassinated in Marseille, France by Veličko Kerin (also known by his revolutionary pseudonym Vlado Chernozemski), an activist of IMRO, in a conspiracy with Yugoslav exiles and radical members of banned political parties in cooperation with the Croatian extreme nationalist Ustaše organisation.

Yugoslav regency

Because Alexander's eldest son, Peter II, was a minor, a regency council of three, specified in Alexander's will, took over the role of King. The council was dominated by the king's cousin Prince Paul.

In the late 1930s, internal tensions continued to increase with Serbs and Croats seeking to establish ethnic federal subdivisions. Serbs wanted Vardar Banovina (later known within Yugoslavia as Vardar Macedonia), Vojvodina, Montenegro united with Serb lands while Croatia wanted Dalmatia and some of Vojvodina. Both sides claimed territory in present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina populated by Bosniak Muslims. The expansion of Nazi Germany in 1938 gave new momentum to efforts to solve these problems and, in 1939, Prince Paul appointed Dragiša Cvetković as prime minister, with the goal of reaching an agreement with the Croatian opposition. Accordingly, on 26 August 1939, Vladko Maček became vice premier of Yugoslavia and an autonomous Banovina of Croatia was established with its own parliament.

These changes satisfied neither Serbs who were concerned with the status of the Serb minority in the new Banovina of Croatia and who wanted more of Bosnia and Herzegovina as Serbian territory. The Croatian nationalist Ustaše were also angered by any settlement short of full independence for a Greater Croatia including all of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Downfall

Fearing an invasion by the Axis powers, Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941, pledging cooperation with the Axis. Massive anti-Axis demonstrations followed in Belgrade.

On 27 March, the regime of Prince Paul was overthrown by a military coup d'état with British support. The 17-year-old Peter II was declared to be of age and placed in power. General Dušan Simović became his Prime Minister. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia withdrew its support for the Axis de facto without formally renouncing the Tripartite Pact. Although the new rulers opposed Nazi Germany, they also feared that if German dictator Adolf Hitler attacked Yugoslavia, the United Kingdom was not in any real position to help. Regardless of this, on 6 April 1941, the Axis powers launched the invasion of Yugoslavia and quickly conquered it. The royal family, including Prince Paul, escaped abroad and were interned by the British in Kenya.[24]

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was soon divided by the Axis into several entities. Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria annexed some border areas outright. A Greater Germany was expanded to include most of Slovenia. Italy added the Governorship of Dalmatia and more than a third of western Slovenia to the Italian Empire. An expanded Croatia was recognized by the Axis as the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH). On paper, the NDH was a kingdom and the 4th Duke of Aosta was crowned as King Tomislav II of Croatia. The rump Serbian territory became a military administration of Germany run by military governors and a Serb civil government led by Milan Nedić. Nedić attempted to gain German recognition of Serbia as a successor state to Yugoslavia and claimed King Peter II as Serbia's monarch. Hungary occupied several northern regions.

Exile of the king

King Peter II, who had escaped into exile, was still recognized as King of the whole state of Yugoslavia by the Allies. From 13 May 1941, the largely Serbian "Yugoslav Army of the Fatherland" (Jugoslovenska vojska u otadžbini, or JVUO, or Četniks) resisted the Axis occupation of Yugoslavia. This anti-German and anti-communist resistance movement was commanded by Royalist General Draža Mihailović. For a long time, the Četniks were supported by the British, the United States, and the Yugoslavian royal government in exile of King Peter II.

However, over the course of the war, effective power changed to the hands of Josip Broz Tito's Communist Partisans. In 1943, Tito proclaimed the creation of the Democratic Federative Yugoslavia (Demokratska federativna Jugoslavija). The Allies gradually recognized Tito's forces as the stronger opposition forces to the German occupation. They began to send most of their aid to Tito's Partisans, rather than to the Royalist Četniks. On 16 June 1944, the Tito–Šubašić agreement was signed which merged the de facto and the de jure government of Yugoslavia.

In early 1945, after the Germans had been driven out, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was formally restored on paper. But real political power was held by Tito's Communist Partisans. On 29 November, King Peter II was deposed by Yugoslavia's Communist Constituent Assembly while he was still in exile. On 2 December, the Communist authorities claimed the entire territory as part of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia. The new Yugoslavia covered roughly the same territory as the Kingdom had, but it was no longer a monarchy.

Foreign policy

Pro-Allied government

The Kingdom nourished a close relationship with the Allies of World War I. This was especially the case between 1920 and 1934 with Yugoslavia's traditional supporters of Britain and France.

Little Entente

From 1920, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia had formed the Little Entente with Czechoslovakia and Romania, with the support of France. The primary aim of the alliance was to prevent Hungary from regaining the territories it had lost after the First World War. The alliance lost its significance in 1937 when Yugoslavia and Romania refused to support Czechoslovakia, then threatened by Germany, in the event of military aggression.

Balkan alliances

In 1924, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia formed a Balkan Bloc with Greece, Romania, and Turkey that was intent on keeping balance on the Balkan peninsula. The alliance was formalized and entrenched on 9 February 1934 when it became the "Balkan Entente". In 1934, with the assassination of King Alexander I by Vlado Chernozemski in Marseilles and the shifting of Yugoslav foreign policy, the alliance crumbled.

Italian coalition

The Kingdom of Italy had territorial ambitions against the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Relations between Italy and the kingdom's predecessors, the Kingdom of Serbia and the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs became sour and hostile during World War I, as Italian and Yugoslav politicians were in dispute over the region of Dalmatia which Italy demanded as part of Italy. These hostile relations were demonstrated on 1 November 1918, when Italian forces sunk the recently captured Austro-Hungarian battleship SMS Viribus Unitis being used by the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. Italy formed a coalition against it with states with similar state designs, heavily influenced by Italy and/or fascism: Albania, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria which lasted from 1924 to 1927.

The 1927 cooperation with Britain and France made Italy withdraw from its anti-Yugoslav alliance. Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini accepted the extreme Croatian nationalist Ustase movement of Ante Pavelić to reside in Italy and use training grounds in Italy to prepare for war with Yugoslavia. Hungary also permitted such Ustase training camps as well. Mussolini allowed Pavelić to reside in Rome.

Friendship agreement

In 1927, in response to the growing Italian expansionism, the royal government of Yugoslavia signed an agreement of friendship and cooperation with the United Kingdom and France.

1935–1941

Officially, the last words of King Aleksandar had been "Save Yugoslavia, and the friendship with France". His successors were well aware of the need to try and do the first, but the second, maintaining close ties with France, was increasingly difficult. There were several reasons for this. By the mid-1930s, France, internally divided, was increasingly unable to play an important role in Eastern Europe and support its allies, many of whom had suffered badly from the economic crisis of that period. By contrast, Germany was increasingly willing to get into barter agreements with the countries of south east Europe. In the process those countries felt it was against their interests to closely follow France. An additional motive to improve relations with Italy and Germany was the fact that Italy supported the Ustase movement. As Maček intimated Italy would support Croatian secession from Yugoslavia, First Regent Prince Paul judged closer relations with Italy were inevitable. In an effort to rob the HSS from potential Italian support, a treaty of friendship was signed between the two countries in 1937. This in fact diminished the Ustasa threat somewhat since Mussolini jailed some of their leaders and temporarily withdrew financial support. In 1938, Germany, annexing Austria, became a neighbour of Yugoslavia. The feeble reaction of France and Britain, later that year, during the Sudeten Crisis convinced Belgrade that a European war was inevitable and that it would be unwise to support France and Britain. Instead, Yugoslavia tried to stay aloof, this in spite of Paul's personal sympathies for Britain and Serbia's establishment's predilections for France. In the meantime, Germany and Italy tried to exploit Yugoslavia's domestic problems, and so did Maček. In the end, the regency agreed to the formation of the Banovina hrvatska in August 1939. This did not put an end to the pressures from Germany and Italy, while Yugoslavia's strategic position deteriorated by the day. It was increasingly dependent on the German market (about 90% of its exports went to Germany), while in April 1939 Italy invaded and annexed Albania. In October 1940 it attacked Greece. by that time, France had already been eliminated from the scene, leaving Britain as Yugoslavia's only potential ally - given that Belgrade had not recognized the Soviet Union. London however wanted to involve Yugoslavia in the war, which it rejected.

From late 1940, Hitler wanted Belgrade to unequivocally choose sides. Pressure intensified, culminating in the signing of the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941. Two days later, Prince Paul was deposed in a coup d'état and his nephew Peter II was proclaimed of age, but the new government, headed by General Simović, assured Germany it would adhere to the Pact. Hitler nonetheless ordered the invasion of Yugoslavia. On 6 April 1941, Belgrade was bombed; on 10 April, the Independent State of Croatia was proclaimed; and on 17 April, the weak Yugoslav Army capitulated.

1941–1944

After the invasion, the Yugoslav royal government went into exile and local Yugoslav forces rose up in resistance to the occupying Axis powers. Initially the monarchy preferred Draža Mihailović and his Serb-dominated Četnik resistance. However, in 1944, the Tito–Šubašić agreement recognised the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia as a provisional government, with the status of the monarchy to be decided at a later date. Three regents—Srđan Budisavljević, a Serb; Ante Mandić, a Croat; and Dušan Sernec, a Slovene—were sworn in at Belgrade on 3 March 1945. They appointed the new government, to be headed by Tito as prime minister and minister of war, with Šubašić as foreign minister, on 7 March.[25]

On 29 November 1945, while still in exile, King Peter II was deposed by the constituent assembly. The Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was internationally recognized as Yugoslavia while Peter II became a pretender.

Demographics

Ethnic groups

| Ethnic group | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs (includes Montenegrins) | 4,665,851 | 38.83 |

| Croats | 2,856,551 | 23.77 |

| Slovenes | 1,024,761 | 8.53 |

| Muslims | 727,650 | 6.05 |

| Macedonians or Bulgarians[26] | 585,558 | 4.87 |

| Other Slavic | 174,466 | 1.45 |

| Germans | 513,472 | 4.27 |

| Hungarians | 472,409 | 3.93 |

| Albanians | 441,740 | 3.68 |

| Romanians, Vlachs and Cincars | 229,398 | 1.91 |

| Turks | 168,404 | 1.40 |

| Jews | 64,159 | 0.53 |

| Italians | 12,825 | 0.11 |

| Others | 80,079 | 0.67 |

| Total | 12,017,323 | 100.00 |

| 1 Source: Banac, Ivo (1992). The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics (2nd printing ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780801494932. (The table represents a reconstruction of Yugoslavia's ethnic structure immediately after the establishment of the kingdom in 1918.) | ||

Until 1929, Serbs, Croats and Slovenes were the constitutional nations, when they were merged into a single "Yugoslav" nationality.

Languages

The following data, grouped by first language, is from the 1921 population census:

- Serbo-Croatian: 8,911,509 (74.36%)

- Slovene: 1,019,997 (8.51%)

- German: 505,790 (4.22%)

- Hungarian: 467,658 (3.9%)

- Arnaut (Albanian): 439,657 (3.67%)

- Romanian: 231,068 (1.93%)

- Turkish: 150,322 (1.25%)

- Czech and Slovak: 115,532 (0.96%)

- Ruthenian: 25,615 (0.21%)

- Russian: 20,568 (0.17%)

- Polish: 14,764 (0.12%)

- Italian: 12,553 (0.11%)

- Others: 69,878 (0.58%)[27][28]

Based on language, the Yugoslavs (collectively Serbs, Croats, Slovenes and Muslims by nationality) constituted 82.87% of the country's population.

Religious groups

- Christians: 10,571,569 (88.21%)

- Orthodox: 5,593,057 (46.67%)

- Roman Catholics: 4,708,657 (39.29%)

- Protestants: 229,517 (1.91%)

- Greek Catholic: 40,338 (0.34%)

- Muslims: 1,345,271 (11.22%)

- Jews: 64,746 (0.54%)

- others: 1,944 (0.02%)

- atheists: 1,381 (0.01%)[27]

Class and occupation

- Agriculture, forestry and fishing - 78.87%

- Industry and handicrafts - 9.91%

- Banking, trade and traffic - 4.35%

- Public service, free profession and military - 3.80%

- Other professions - 3.07%[29]

Education

The Kingdom had three universities: the University of Belgrade, University of Zagreb and the University of Ljubljana, located in what were then the most developed cities in the country.

Rulers

Kings

- Peter I (1 December 1918 – 16 August 1921; Prince Regent Alexander ruled in the name of the King)

- Alexander I (16 August 1921 – 9 October 1934)

- Peter II (9 October 1934 – 29 November 1945; in exile from 13/14 April 1941)

- Regency headed by Prince Paul (9 October 1934 – 27 March 1941)

Prime Ministers 1918–1941

|

|

Prime Ministers-in-exile 1941–1945

- 1941–1942 – Dušan Simović

- 1942–1943 – Slobodan Jovanović

- 1943 – Miloš Trifunović

- 1943–1944 – Božidar Purić

- 1944–1945 – Ivan Šubašić

- 1945 – Josip Broz Tito

Subdivisions

The subdivisions of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia existed successively in three different forms. From 1918 to 1922, the kingdom maintained the pre–World War I subdivisions of Yugoslavia's predecessor states. In 1922, the state was divided into thirty-three oblasts (provinces). In 1929, after the establishment of the January 6 Dictatorship, a new system of nine banovinas (regions) was implemented by royal decree. In 1939, as an accommodation to Yugoslav Croats in the Cvetković-Maček Agreement, a single Banovina of Croatia was formed from two of these banovinas (and from sections of others).

Sport

The most popular sport in the Kingdom was association football. The Yugoslav Football Association was founded in Zagreb in 1919. It was based in Zagreb until the 6 January Dictatorship, when the association was moved to Belgrade. From 1923, a national championship was held annually. The national team played its first match at the 1920 Summer Olympics. It also participated in the inaugural FIFA World Cup, finishing fourth.

Other popular sports included water polo, which was dominated nationally by the Croatian side VK Jug.

The Kingdom participated at the Olympic Games from 1920 until 1936. During this time, the country won eight medals, all in gymnastics and six of these were won by Leon Štukelj, a Slovene who was the most nominated gymnast of that time.

See also

- Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes parliamentary election, 1923

- Republic of Prekmurje

- Slovene March (Kingdom of Hungary)

Notes

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has received recognition as an independent state from 110 out of 193 United Nations member states. |

References

- ↑ Busch, Birgitta; Kelly-Holmes, Helen (2004). Language, Discourse and Borders in the Yugoslav Successor States. Multilingual Matters. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-85359-732-9.

- ↑ Alexander, Ronelle (2013). "Language and Identity: The Fate of Serbo-Croatian". In Daskalov, Rumen; Marinov, Tchavdar. Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 371. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

Now, however, the official language of the new state, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, bore the unwieldy name Serbo-Croato-Slovene (srpsko-hrvatsko-slovenački).

- ↑ Wojciechowski, Sebastian; Burszta, Wojciech J.; Kamusella, Tomasz (2006). Nationalisms across the globe: an overview of nationalisms in state-endowed and stateless nations. 2. School of Humanities and Journalism. p. 79. ISBN 978-83-87653-46-0.

Similarly, the 1921 Constitution declared Serbocroatoslovenian as the official and national language of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenians.

- ↑ Kamusella, Tomasz (2009). The politics of language and nationalism in modern Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 228, 297. ISBN 978-0-230-55070-4.

- 1 2 "Kraljevina Jugoslavija! Novi naziv naše države. No, mi smo itak med seboj vedno dejali Jugoslavija, četudi je bilo na vseh uradnih listih Kraljevina Srbov, Hrvatov in Slovencev. In tudi drugi narodi, kakor Nemci in Francozi, so pisali že prej v svojih listih mnogo o Jugoslaviji. 3. oktobra, ko je kralj Aleksander podpisal “Zakon o nazivu in razdelitvi kraljevine na upravna območja", pa je bil naslov kraljevine Srbov, Hrvatov in Slovencev za vedno izbrisan." (Naš rod ("Our Generation", a monthly Slovenian language periodical), Ljubljana 1929/30, št. 1, str. 22, letnik I.)

- ↑ J. B. Hoptner (1963). "Yugoslavia In Crisis 1934-1941". Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Walter R. Roberts (1973). Tito, Mihailović, and the Allies, 1941-1945. Rutgers University Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-8135-0740-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Spencer Tucker. Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2005. Pp. 1189.

- ↑ History of the municipal theatre from Corfu city hall Quote: "The Municipal Theatre was not only an Art-monument but also a historical one. On its premises the exiled Serbian parliament, held meetings in 1916, which decided the creation of the new Unified Kingdom of Yugoslavia."

- ↑ Hehn, Paul N. (2005) A Low Dishonest Decade: Italy, the Powers and Eastern Europe, 1918-1939., Chapter 2, Mussolini, Prisoner of the Mediterranean

- ↑ Čermelj, L. (1955). Kako je prišlo do prijateljskega pakta med Italijo in kraljevino SHS (How the Friendsjip Treaty between Italy and the Kingdom of SHS Came About in 1924), Zgodovinski časopis, 1-4, p.195, Ljubljana

- ↑ Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe, Geographical perspectives on the human past, George W. White, Rowman & Littlefield, 2000, ISBN 0847698092, p. 236.

- ↑ Rudolf B. Schlesinger (1988). Comparative law: cases, text, materials. Foundation Press. p. 328.

Some countries, notably the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, had preserved enclaves of Islamic law (relating to personal...)..

- ↑ Lampe 2000, p. 112.

- ↑ Gligorijević, Branislav (1979) Parliament i političke stranke u Jugoslaviji 1919–1929 Institut za savremenu istoriju, Narodna knjiga, Belgrade, OCLC 6420325

- ↑ Balkan Politics, Time Magazine, 31 March 1923

- ↑ Elections, Time Magazine, 23 February 1925

- ↑ The Opposition, Time Magazine, 6 April 1925

- ↑ Bartulin, Nevenko (2013). The Racial Idea in the Independent State of Croatia: Origins and Theory. Brill Publishers. p. 124.

- ↑ Realite sur l'attentat de Marseille contre le roi Alexandre Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Einstein accuses Yugoslavian rulers in savant's murder, New York Times. 6 May 1931. mirror

- ↑ "Raditch left tale of Yugoslav plot". New York Times. 23 August 1931. p. N2. Retrieved 6 December 2008. mirror

- ↑ "Nevada Labor. Yesterday, today and tomorrow". Nevadalabor.com. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ↑ "Prince Paul of Yugoslavia exonerated of war crimes" (PDF). The Times. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-14.

- ↑ Josef Korbel, Tito's Communism (University of Denver Press, 1951), 22.

- 1 2 Banac, Ivo. The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press, 1988. pp. 49–53, 58. ISBN 9780801494932

- 1 2 Group of Authors (1997). Istorijski atlas (1st ed.). Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva & Geokarta, Belgrade. p. 91. ISBN 86-17-05594-4.

- ↑ "Краљевина Југославија дефинитивни резултати пописа становништва од 21 јануара 1921 год.", Сарајево, Државна Штампарија, 1932, page 3

- ↑ Group of Authors (1997). Istorijski atlas (1st ed.). Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva & Geokarta, Belgrade. p. 86. ISBN 86-17-05594-4.

Sources

- Lampe, John R. (28 March 2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7.

- Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9493-1.

- Todor Radivojević (1935). Kraljevina Jugoslavija s ilustrovanom geografskom čitankom: za četvrti razred srednjih škola. T. Jovanović i Vujić.

- Branko Petranović (1988). Istorija Jugoslavije 1918-1988: knj. Kraljevina Jugoslavija 1914-1941. Nolit.

- Pavle Vujević (1930). Kraljevina Jugoslavija: geografski i etnografski pregled. Štamparija "Davidović" Pavlovića i druga.

- Sabrina P. Ramet (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- Snežana Trifunovska (1994). Yugoslavia Through Documents: From Its Creation to Its Dissolution. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-2670-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kingdom of Yugoslavia. |

- (English) Full text of the 1931 Constitution at the Wayback Machine (archived 21 October 2009)

| Timeline of Yugoslav statehood | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1918 | 1918–1929 | 1929–1945 | 1941–1945 | 1945–1946 | 1946–1963 | 1963–1992 | 1991/1992–2003 | 2003–2006 | 2006–2008 | 2008– | |

| Slovenia | See also Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia 1868–1918 Kingdom of Dalmatia 1815–1918 Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina 1878–1918 |

See also Banat, Bačka and Baranja 1918–1919 Italian province of Zadar 1920–1947 |

Annexed bya Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany |

Democratic Federal Yugoslavia 1945–1946 Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia 1946–1963 Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 1963–1992 Consisted of the Socialist Republics of |

Ten-Day War | ||||||

| Dalmatia | Independent State of Croatia 1941–1945 Puppet state of Nazi Germany. Parts annexed by Fascist Italy. Međimurje and Baranja annexed by Hungary. |

Croatian War of Independence | |||||||||

| Slavonia | |||||||||||

| Croatia | |||||||||||

| Bosnia | Bosnian War Consists of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1995–present), Republika Srpska (1995–present) and Brčko District (2000–present). | ||||||||||

| Herzegovina | |||||||||||

| Vojvodina | Part of the Délvidék region of Hungary | Autonomous Banatd (part of the German Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia) |

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia | State Union of Serbia and Montenegro | |

Includes the autonomous province of Vojvodina | |||||

| Serbia | Kingdom of Serbia 1882–1918 |

Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia 1941–1944 e | |||||||||

| Kosovo | Part of the Kingdom of Serbia 1912–1918 |

Mostly annexed by Albania 1941–1944 along with western Macedonia and south-eastern Montenegro |

| ||||||||

| Metohija | Kingdom of Montenegro 1910–1918 Metohija controlled by Austria-Hungary 1915–1918 | ||||||||||

| Montenegro | Protectorate of Montenegrof 1941–1944 |

| |||||||||

| Macedonia | Part of the Kingdom of Serbia 1912–1918 |

Annexed by the Kingdom of Bulgaria 1941–1944 |

| ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

Coordinates: 44°49′14″N 20°27′44″E / 44.82056°N 20.46222°E