Canadian nationalism

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Canada |

|---|

|

| History |

| Topics |

| Research |

| Portal |

Canadian nationalism seeks to promote the unity, independence, and well-being of Canada and Canadians.[1] Canadian nationalism has been a significant political force since the 19th century and has typically manifested itself as seeking to advance Canada's independence from influence of the United Kingdom and especially the United States of America.[1] Since the 1960s, most proponents of Canadian nationalism have advocated a civic nationalism due to Canada's cultural diversity that specifically has sought to equalize citizenship, especially for Québécois, who historically faced assimilationist pressure from English Canadian-dominated governments.[2] Canadian nationalism became an important issue during the 1988 Canadian general election that focused on the then-proposed Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement, with Canadian nationalists opposing the agreement - saying that the agreement would lead to inevitable complete assimilation and domination of Canada by the United States.[3] During the 1995 Quebec referendum on sovereignty that sought to determine whether Quebec would become a sovereign state or whether it would remain in Canada, Canadian nationalists and federalists supported the "no" side while Quebec nationalists supported the "yes" side, resulting in a razor-thin majority in favour of the "no" side that supported Quebec remaining in Canada.

The aforementioned version opts for a certain level of sovereignty, while remaining within the greater British Empire or Commonwealth. The Canadian Tories are such example. Canadian Tories were also strongly opposed to free trade with the United States, fearing economic and cultural assimilatation. On the other hand, French Canadian nationalism has its roots as early as pre-confederation. Although a more accurate portrait of French Canadian nationalism is illustrated by such figures as Henri Bourassa during the first half of the twentieth century. Bourassa advocated for a nation less reliant on Great Britain whether politically, economically or militarily, although he was not, at the same time, opting for a republic which was the case for the radical French-speaking reformers in the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837. Nor were Bourassa or others necessarily advocating for a provincial nationalism, i.e. for the separation of Quebec from Canada which became a strong component in Quebec politics during the Quiet Revolution and especially through the rise of the Parti Québécois in 1968.

History

The goal of all economic and political nationalists has been the creation and then maintenance of Canadian sovereignty. During Canada's colonial past there were various movements in both Upper Canada (present day Ontario) and Lower Canada (present day Quebec) to achieve independence from the British Empire. These culminated in the failed Rebellions of 1837. These movements had republican and pro-American tendencies and many of the rebels fled to the US following the failure of the rebellion. Afterwards Canadian patriots began focusing on self-government and political reform within the British Empire. This was a cause championed by early Liberals such as the Reform Party (pre-Confederation) and the Clear Grits, while Canada's early Conservatives, supported by loyalist institutions and big business, supported stronger links to Britain. Following the achievement of constitutional independence in 1867 (Confederation) both of Canada's main parties followed separate nationalistic themes. The early Liberal Party of Canada generally favoured greater diplomatic and military independence from the British Empire while the early Conservative Party of Canada fought for economic independence from the United States.

Free trade with the U.S.

Starting before Confederation in 1867 the debate between free trade and protectionism was a defining issue in Canadian politics. Nationalists, along with British loyalists, were opposed to the idea of free trade or reciprocity for fear of having to compete with American industry and losing sovereignty to the United States. This issue dominated Canadian politics during the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the Tories taking a populist, anti-free trade stance. Conservative leader Sir John A. Macdonald advocated an agenda of economic nationalism, known as the National Policy. This was very popular in the industrialized Canadian east. While the Liberal Party of Canada took a more classical liberal approach and supported the idea of an "open market" with the United States, something feared in eastern Canada but popular with farmers in western Canada.[4] The National Policy also included plans to expand Canadian territory into the western prairies and populate the west with immigrants.

In each "free trade election", the Liberals were defeated, forcing them to give up on the idea. The issue was revisited in the 1980s by Progressive Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. Mulroney reversed his party's protectionist tradition, and, after claiming to be against free trade during his leadership campaign in 1983, went forward with negotiations for a free trade agreement with the United States. His government believed that this would cure Canada's ills and unemployment, which had been caused by a growing deficit and a terrible economic recession during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The agreement was drawn up in 1987 and an election was held on the issue in 1988. The Liberals, in a reversal of their traditional role, campaigned against free trade under former Prime Minister John Turner. The Tories won the election with a large majority, partially due to Mulroney's support in Quebec among Quebec nationalists to whom he promised "distinct society" status for their province.

After the election of 1988, opponents of free trade pointed to the fact that the PC Party of Brian Mulroney received a majority of seats in parliament with only 43% of the vote while together the Liberal Party and New Democratic Party both of whom opposed the agreement received 51% of the vote, showing opposition from a clear majority of the population.

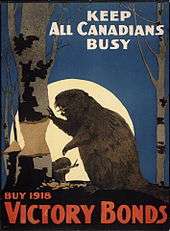

World wars

The impact of World War I on the evolution of Canada’s identity is debated by historians. While there is a consensus that on the eve of the war, most English speaking Canadians had a hybrid imperial-national identity, the war's effects on Canada’s emergence as a nation are complex. The Canadian media often refers to the First World War and, in particular, the Battle of Vimy Ridge, as marking “the birth of a nation.”[5] Some historians consider the First World War to be Canada’s “war of independence.”[6] They argue that the war decreased the extent to which Canadians identified with the British Empire and intensified their sense of being Canadians first and British subjects second.

This sense was expressed during the Chanak crisis when, for the first time, the Canadian government stated that a decision by the British government to go to war would not automatically entail Canadian participation.

Other historians robustly dispute the view that World War I undermined the hybrid imperial-national identity of English-speaking Canada. Phillip Buckner states that: “The First World War shook but did not destroy this Britannic vision of Canada. It is a myth that Canadians emerged from the war alienated from, and disillusioned with, the imperial connection." He argues that most English-speaking Canadians "continued to believe that Canada was, and should continue to be, a 'British' nation and that it should cooperate with the other members of the British family in the British Commonwealth of Nations.”[7] Nevertheless, there are two possible mechanisms whereby World War I may have intensified Canadian nationalism: 1) Pride in Canada’s accomplishments on the battlefield demonstrably promoted Canadian patriotism, and 2) the war distanced Canada from Britain in that Canadians reacted to the sheer slaughter on the Western Front by adopting an increasingly anti-British attitude.[6]

Still, Governor General The Lord Tweedsmuir raised the ire of imperialists when he said in Montreal in 1937: "a Canadian's first loyalty is not to the British Commonwealth of Nations, but to Canada and Canada's King."[8] The Montreal Gazette dubbed the statement "disloyal."[9]

Québécois nationalism

Another early source of pan-Canadian nationalism came from Quebec in the early 20th century. Henri Bourassa, Mayor of Montebello and one-time Liberal Member of Parliament created the Canadian Nationalist League (Ligue nationaliste canadienne) supporting an independent role for Canada in foreign affairs opposed to both British and American imperialism.[10] Bourassa also supported Canadian economic autonomy. Bourassa was instrumental in defeating Sir Wilfrid Laurier in the federal election of 1911 over the issue of a Canadian Navy controlled by the British Empire, something he furiously opposed. In so doing, he aided the Conservative Party of Sir Robert Borden in that election, a party with strong British imperialist sympathies.[11]

In the federal election of 1917 he was also instrumental in opposing the Borden government's plan for conscription and as a result assisted the Laurier Liberals in Quebec. His vision of a unified, bi-cultural, tolerant and sovereign Canada remains an ideological inspiration to many Canadian nationalists. Alternatively his French Canadian nationalism and support for maintaining French Canadian culture would inspire Quebec nationalists many of whom were supporters of the Quebec sovereignty movement.

Nationalist politics

Modern attempts at forming a popular Canadian nationalist party have failed. The National Party of Canada was the most successful of recent attempts. Led by former publisher Mel Hurtig the Nationals received more than 183,000 votes or 1.38% of the popular vote in the 1993 election. Infighting however led to the party's demise shortly afterwards. This was followed by the formation of the Canadian Action Party in 1997. Created by a former Liberal Minister of Defence, Paul Hellyer, the CAP has failed to attract significant attention from the electorate since that time. An organic farmer and nationalist activist from Saskatchewan named David Orchard attempted to bring a nationalist agenda to the forefront of the former Progressive Conservative Party of Canada. In spite of attracting thousands of new members to a declining party he was unsuccessful in taking over the leadership and preventing the merger with the former Canadian Alliance.[12][13]

Various activist/lobby groups such as the Council of Canadians, along with other progressive, environmentalist and labour groups have campaigned tirelessly against attempts to integrate the Canadian economy and harmonize government policies with that of the United States. They point to threats allegedly posed to Canada's environment, natural resources, social programs, the rights of Canadian workers and cultural institutions. These echo the concerns of a large segment of the Canadian population. The nationalist Council of Canadians took a role of leadership in protesting discussions on the Security and Prosperity Partnership and earlier talks between previous Canadian and U.S. governments on "deep integration".

Criticism of Canadian nationalism

Critics often point out that there is a marked difference between "Canadian nationalism" and Canadian patriotism, and that nationalistic organizations such as the Council of Canadians are biased or excessively critical of right-wing and centrist politicians and parties who support varying degrees of integration with the United States. In particular, the Council of Canadians routinely characterizes Canadian "neoconservatives" as being the individuals most responsible for destroying Canadian sovereignty. Conservative critics will thus often characterize modern Canadian nationalism as being a primarily leftist movement, allied too heavily with the Canadian labour movement.

There is also a political faction on the Left critical of what they call "left nationalism", arguing that it is a mistake to combine left politics with nationalism. Political currents which oppose left nationalism include the International Socialists, the New Socialist Group, Socialist Action and Socialist Voice. However these organizations are marginal in terms of membership when compared to Canadian organizations of the Left that choose to embrace nationalism (such as the Council of Canadians and Canadian Labour Congress). Marxist theoreticians who have written critiques of left nationalism include William Carroll, David McNally, Steve Moore and Debi Wells. In 2003, the debate took written form in the pages of Canadian Dimension and on a web-based publication ViveleCanada.ca.

List of self-identified nationalist groups in Canada

Left-wing

- Centre and moderate left

- New Politics Initiative

- Canadian Action Party

- Vive le Canada

- Canadian National Federation

- Committee for an Independent Canada

- The Council of Canadians

- Far-left

- The Waffle - the former far-left faction of the New Democratic Party, purged by former leader David Lewis in the 1970s.

- Ginger Group

Right-wing

- Centre-right and moderate right

- Progressive Conservative Party of Canada - especially under John Diefenbaker, Joe Clark, Jean Charest, and members such as David Orchard

- Progressive Canadian Party

- Far-right

- National Unity Party - former Fascist and National socialist party banned in 1940.

Canadian government departments in charge of cultural nationalism

Canadian nationalist leaders

- William Lyon Mackenzie

- Louis Joseph Papineau

- Sir John A. Macdonald

- Sir George-Étienne Cartier

- Henri Bourassa

- James Laxer

- David Orchard

- Maude Barlow

- Mel Hurtig

- John Diefenbaker

- Sheila Copps

- Jean Chrétien

- Pierre Trudeau

Canadian anti-nationalists

See also

- Anthems and nationalistic songs of Canada

- Canadian cultural protectionism

- Immigration Watch Canada

- Canadian identity

- Canadianism

- Multiculturalism in Canada

Notes

- 1 2 Motyl 2001, pp. 68.

- ↑ Recent social trends in Canada, 1960-2000. Pp. 415.

- ↑ Motyl 2001, pp. 69.

- ↑ Bélanger, Claude (April 2005). "The National Policy and Canadian Federalism". Studies on the Canadian Constitution and Canadian Federalism. Marianopolis College.

- ↑ Nersessian, Mary (April 9, 2007). Vimy battle marks birth of Canadian nationalism Archived February 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.. CTV.ca

- 1 2 Cook, Tim (2008). Shock troops: Canadians fighting the Great War, 1917-1918. Toronto: Viking.

- ↑ Buckner, Philip, ed. (2006). Canada and the British World: Culture, Migration, and Identity. p. 1. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

- ↑ Smith, Janet Adam; John Buchanan, a Biography; London, 1965; p. 423

- ↑ Time: Roya Visit; October 21, 1957

- ↑ Levitt, Joseph. Bourassa, Henri. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica.ca.

- ↑ Neatby, H. Blair (1973). Laurier and a Liberal Quebec: A Study in Political Management. Richard T. Clippingdale., ed. McClelland and Steward Limited. Questia.com.

- ↑ http://www.pgib.ca/2cards/pages/english/content/history/PCRace.htm

- ↑

References

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volume II. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-227230-7.

Further reading

- Asselin, Olivar (1909). A Quebec View of Canadian nationalism: An Essay by a dyed-in-the-wool French-Canadian on the Best Means of Ensuring the Greatness of the Canadian fatherland. Montreal: Guertin Printing Company, Ltd. p. 61.

- Azzi, Stephen (1999). Walter Gordon and the Rise of Canadian Nationalism. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 300. ISBN 0-7735-1840-1.

- Bailey, Alfred Goldsworthy (1972). Culture and Nationality: Essays. Toronto & Montreal: McClelland and Stewart. p. 224.

- Bauhn, Per (1995). Multiculturalism and Nationhood in Canada: The Cases of First Nations and Quebec. Lund, Sweden: Lund University Press. p. 102.

- Berger, Carl (1969). Imperialism and Nationalism, 1884-1914: A Conflict in Canadian Thought. Toronto: Copp Clark. p. 119.

- Berton, Pierre (1982). Why We Act like Canadians: A Personal Exploration of our National Character. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. p. 113. ISBN 0-7710-1363-9.

- Boyd, John (1919). The Future of Canada: Canadianism or Imperialism. Montreal: Librairie Beauchemin Limited. p. 106.

- Raymond Breton; Jeffrey G. Reitz; Victor F. Valentine (1980). Cultural boundaries and the cohesion of Canada. Montréal: Institut de recherches politiques. p. 422.

- Brown, Brian A. (1976). Separatism. Dawson Creek: Echo Pub. p. 200. ISBN 0-920252-01-X.

- Brunet, Michel (1954). Canadians et Canadiens : études sur l'histoire et la pensée des deux Canadas (in French). Montréal: Fides. p. 173.

- Brunet, Michel (1958). La Présence anglaise et les Canadiens : études sur l'histoire et la pensée des deux Canadas (in French). Montréal: Beauchemin. p. 292.

- Collins, Richard (1990). Culture, Communication, and National Identity: The Case of Canadian Television. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 367. ISBN 0-8020-2733-4.

- Cook, Ramsay (1986). Canada, Quebec, and the Uses of Nationalism. Toronto: M&S. p. 294. ISBN 0-7710-2254-9.

- Cook, Ramsay (1971). The Maple Leaf Forever. Essays on Nationalism and Politics in Canada. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. p. 253.

- Corse, Sarah M. (1997). Nationalism and Literature: The Politics of Culture in Canada and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-521-57002-2.

- Couture, Claude (1998). Paddling with the Current: Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Étienne Parent, Liberalism, and Nationalism in Canada. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-88864-313-6.

- Crean, Susan (1983). Two Nations: An essay on the Culture and Politics of Canada and Quebec in a World of American Preeminence. Toronto: J. Lorimero. p. 167. ISBN 0-88862-381-X.

- Doran, Charles F. (1995). Being and Becoming Canada. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Periodicals Press. p. 236. ISBN 0-8039-5884-6.

- Foster, William Alexander (1871). Canada First, or, Our New Nationality. An address by W.A. Foster. Toronto: Adam, Stevenson & Co. p. 36.

- Giroux, Maurice (1967). Essai politique sur la crise des deux nations canadiennes; : la pyramide de Babel (in French). Montréal: Editions de Sainte-Marie. p. 138.

- Grant, George (1965). Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism. Toronto & Montreal: McClelland and Stewart Limited. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-7735-3010-2.

- Gwyn, Richard (1995). Nationalism without walls : the unbearable lightness of being Canadian. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. p. 304. ISBN 0-7710-3717-1.

- Heisey, Alan (1973). The Great Canadian Stampede, The rush to economic nationalism: right or wrong?. Toronto: Griffin Press Limited. ISBN 0-88760-062-X.

- Heron, Craig, ed. (1977). Imperialism, Nationalism and Canada: Essays from the Marxist Institute of Toronto. Toronto: New Hogtown Press. p. 206. ISBN 0-919940-05-6.

- Lower, Arthur Reginald Marsden (1975). History and Myth. Arthur Lower and the making of Canadian Nationalism. University of British Columbia Press. p. 339. ISBN 0-7748-0035-6.

- MacLaren, Roy (2006). Commissions High: Canada in London, 1870-1971. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 567. ISBN 978-0-7735-3036-2.

- Madison, Gary Brent (2000). Is there a Canadian philosophy? Reflections on the Canadian Identity. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-7766-0514-3.

- Maheux, Arthur (1944). Problems of Canadian Unity. Québec: les Éditions des Bois-Francs. p. 186.

- Manning, Erin (2003). Ephemeral Territories: Representing Nation, Home, and Identity in Canada. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 187. ISBN 0-8166-3924-8.

- Moore, William Henry (1918). The Clash! A study in Nationalities. London: Dent & Sons. p. 333.

- Morris, Raymond N. (1977). Three Scales of Inequality: Perspectives on French-English Relations. Don Mills: Longman Canada. p. 300. ISBN 0-7747-3035-8.

- Morton, William Lewis (1961). The Canadian Identity. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 125.

- Nelles, Viv. (1973). Nationalism or Local Control: Responses to George Woodcock. Toronto: New Press. p. 97.

- Paquet, Gilles; Jean-Pierre Wallot (1983). Nouvelle-France/Québec/Canadas: A World of Limited Identities. Ottawa: Faculty of Administration, University of Ottawa. p. 73.

- Radwanski, George (1992). The Will of a Nation: Awakening the Canadian Spirit. Toronto: Stoddart. p. 195. ISBN 0-7737-2637-3.

- Resnick, Philip (2005). The European Roots of Canadian Identity. Broadview Press. p. 125. ISBN 1-55111-705-3.

- Resnick, Philip (1977). The Land of Cain: Class and Nationalism in English Canada, 1945-1975. Vancouver: New Star Books. p. 297. ISBN 0-919888-68-2.

- Rotstein, Abraham (1972). Independence: The Canadian Challenge. Toronto: The Committee for an Independent Canada. p. 279.

- Rotstein, Abraham (1973). The Precarious Homestead; Essays on Economics, Technology and Nationalism. Toronto: New Press. p. 331. ISBN 0-88770-710-6.

- Russell, Peter, ed. (1966). Nationalism in Canada, by the University League for Social Reform. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Company of Canada. p. 377.

- Saint-Laurent, Louis (1961). National unity of Canada: First Annual Kenneth E. Norris Memorial Lecture, November 9, 1961. An address by The Right Honourable Louis S. St-Laurent. Association of Alumni, Sir George Williams University. p. 24.

- Samuels, H. Raymond II (1997). National Identity in Canada and Cosmopolitan Community. Ottawa: The Agora Cosmopolitan. p. 288. ISBN 0-9681906-0-X.

- Sheffe, Norman, ed. (1971). Canadian / Canadien. Toronto: Ryerson Educational Division, McGraw-Hill Co. of Canada. p. 121. ISBN 0-07-092860-6.

- Siegfried, André (1907). The Race Question in Canada. London: Eveleigh Nash. p. 343.

- Smith, Allan (1994). Canada: An American Nation? Essays on Continentalism, Identity and the Canadian Frame of Mind. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 398. ISBN 0-7735-1229-2.

- Stanfield, Robert L. (1978). Nationalism: A Canadian Dilemma?. Sackville, N.B.: Mount Allison University. p. 41. ISBN 0-88828-017-3.

- Studin, Irvin, ed. (2006). What is a Canadian? Forty-Three Thought-Provoking Responses. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-7710-8321-1.

- Taylor, Charles (1993). Reconciling the Solitudes: Essays on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-7735-1105-9.

- Thacker, Robert (1996). "Sharing the Continent" Still: English Canadian Nationalism and Cultural Sovereignty. Bowling Green, Ohio: Canadian Studies Center, Bowling Green State University. p. 18.

- Wade, Mason, ed. (1960). Canadian dualism : studies of French-English relations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 427.

- Wallace, William Stewart (1927). The Growth of Canadian National Feeling. Toronto: MacMillan. p. 85.

- Webber, Jeremy H. A. (1994). Reimagining Canada: Language, Culture, Community and the Canadian Constitution. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 373. ISBN 0-7735-1146-6.

- Wilden, Anthony (1980). The Imaginary Canadian. Vancouver: Pulp Press. p. 261. ISBN 0-88978-088-9.

- Woodcock, George (1989). The Century that Made Us: Canada 1814-1914. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press Canada. p. 280. ISBN 0-19-540703-2.

- Wright, Robert W. (1993). Economics, Enlightenment, and Canadian Nationalism. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-7735-0980-1.

- Young, James (1891). Canadian Nationality. A glance at the present and future, being an address delivered by the Hon. James Young, of Galt, before the members of the National Club of Toronto, on the evening of the 21st April, '91. Toronto: R.G. McLean.