Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

| |

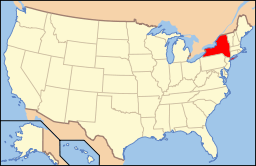

Location in Manhattan | |

| Established | April 13, 1870[1][2][3] |

|---|---|

| Location | 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, New York 10028 |

| Coordinates | 40°46′46″N 73°57′47″W / 40.779447°N 73.96311°W |

| Visitors |

5.2 million (2008)[2]

|

| Director | Thomas P. Campbell |

| Public transit access |

Subway: Bus: M1, M2, M3, M4, M79, M86 |

| Website | |

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art | |

|

Elevation by Simon Fieldhouse | |

| Built | 1874 |

| Architect | Richard Morris Hunt; also Calvert Vaux; Jacob Wrey Mould |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| NRHP Reference # | 86003556 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 29, 1972[5] |

| Designated NHL | June 24, 1986[6] |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially "the Met",[7] is located in New York City and is the largest art museum in the United States, and is among the most visited art museums in the world.[8] Its permanent collection contains over two million works,[9] divided among seventeen curatorial departments.[10] The main building, on the eastern edge of Central Park along Manhattan's Museum Mile, is by area one of the world's largest art galleries. A much smaller second location, The Cloisters at Fort Tryon Park in Upper Manhattan, contains an extensive collection of art, architecture, and artifacts from Medieval Europe.[11]

The permanent collection consists of works of art from classical antiquity and ancient Egypt, paintings and sculptures from nearly all the European masters, and an extensive collection of American and modern art. The Met maintains extensive holdings of African, Asian, Oceanian, Byzantine, Indian, and Islamic art.[12] The museum is home to encyclopedic collections of musical instruments, costumes and accessories, as well as antique weapons and armor from around the world.[13] Several notable interiors, ranging from first-century Rome through modern American design, are installed in its galleries.[14]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art was founded in 1870. The founders included businessmen and financiers, as well as leading artists and thinkers of the day, who wanted to open a museum to bring art and art education to the American people.[3] It opened on February 20, 1872, and was originally located at 681 Fifth Avenue.[15]

Collections

The Met's permanent collection is curated by seventeen separate departments, each with a specialized staff of curators and scholars, as well as six dedicated conservation departments and a Department of Scientific Research.[10] The permanent collection includes works of art from classical antiquity and ancient Egypt, paintings and sculptures from nearly all the European masters, and an extensive collection of American and modern art. The Met maintains extensive holdings of African, Asian, Oceanian, Byzantine, and Islamic art.[12] The museum is also home to encyclopedic collections of musical instruments, costumes and accessories, and antique weapons and armor from around the world.[13] A number of notable interiors, ranging from 1st century Rome through modern American design, are permanently installed in the Met's galleries.[14]

In addition to its permanent exhibitions, the Met organizes and hosts large traveling shows throughout the year.

The director of the museum is Thomas P. Campbell, a long-time curator, who replaced Philippe de Montebello following his retirement at the end of 2008.[16][17]

Ancient Near Eastern art

Beginning in the late 19th century, the Met started to acquire ancient art and artifacts from the Near East. From a few cuneiform tablets and seals, the Met's collection of Near Eastern art has grown to more than 7,000 pieces.[18] Representing a history of the region beginning in the Neolithic Period and encompassing the fall of the Sasanian Empire and the end of Late Antiquity, the collection includes works from the Sumerian, Hittite, Sasanian, Assyrian, Babylonian, and Elamite cultures (among others), as well as an extensive collection of unique Bronze Age objects. The highlights of the collection include a set of monumental stone lamassu, or guardian figures, from the Northwest Palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II.[19]

Arms and armor

The Met's Department of Arms and Armor is one of the museum's most popular collections. The distinctive "parade" of armored figures on horseback installed in the first-floor Arms and Armor gallery is one of the most recognizable images of the museum, which was organized in 1975 with the help of the Russian immigrant and arms and armors' scholar, Leonid Tarassuk (1925–90). The department's focus on "outstanding craftsmanship and decoration", including pieces intended solely for display, means that the collection is strongest in late medieval European pieces and Japanese pieces from the 5th through the 19th centuries. However, these are not the only cultures represented in Arms and Armor; the collection spans more geographic regions than almost any other department, including weapons and armor from dynastic Egypt, ancient Greece, the Roman Empire, the ancient Near East, Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, as well as American firearms (especially Colt firearms) from the 19th and 20th centuries. Among the collection's 14,000 objects[20] are many pieces made for and used by kings and princes, including armor belonging to Henry VIII of England, Henry II of France, and Ferdinand I of Germany.

Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

Though the Met first acquired a group of Peruvian antiquities in 1882, the museum did not begin a concerted effort to collect works from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas until 1969, when American businessman and philanthropist Nelson A. Rockefeller donated his more than 3,000-piece collection to the museum. Today, the Met's collection contains more than 11,000 pieces from sub-Saharan Africa, the Pacific Islands, and the Americas and is housed in the 40,000-square-foot (4,000 m2) Rockefeller Wing on the south end of the museum.[21]

The collection ranges from 40,000-year-old Australian Aboriginal rock paintings, to a group of 15-foot-high (4.6 m) memorial poles carved by the Asmat people of New Guinea, to a priceless collection of ceremonial and personal objects from the Nigerian Court of Benin donated by Klaus Perls.[22] The range of materials represented in the Africa, Oceania, and Americas collection is undoubtedly the widest of any department at the Met, including everything from precious metals to porcupine quills.

Asian art

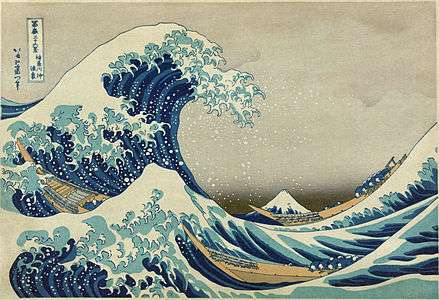

The Met's Asian department holds a collection of Asian art, of more than 35,000 pieces,[23] that is arguably the most comprehensive in the US. The collection dates back almost to the founding of the museum: many of the philanthropists who made the earliest gifts to the museum included Asian art in their collections. Today, an entire wing of the museum is dedicated to the Asian collection, and spans 4,000 years of Asian art. Every Asian civilization is represented in the Met's Asian department, and the pieces on display include every type of decorative art, from painting and printmaking to sculpture and metalworking. The department is well known for its comprehensive collection of Chinese calligraphy and painting, as well as for its Nepalese and Tibetan works. However, not only "art" and ritual objects are represented in the collection; many of the best-known pieces are functional objects. The Asian wing also contains a complete Ming Dynasty-style garden court, modeled on a courtyard in the Garden of the Master of the Fishing Nets in Suzhou.

The Costume Institute

The Museum of Costume Art was founded by Aline Bernstein and Irene Lewisohn.[24] In 1937, they merged with the Met and became its Costume Institute department. Today, its collection contains more than 35,000 costumes and accessories.[25] The Costume Institute used to have a permanent gallery space in what was known as the "Basement" area of the Met because it was downstairs at the bottom of the Met facility. However, due to the fragile nature of the items in the collection, the Costume Institute does not maintain a permanent installation. Instead, every year it holds two separate shows in the Met's galleries using costumes from its collection, with each show centering on a specific designer or theme.

In past years, Costume Institute shows organized around famous designers such as Cristóbal Balenciaga, Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent, and Gianni Versace; and style doyenne like Diana Vreeland, Mona von Bismarck, Babe Paley, Jayne Wrightsman, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Nan Kempner, and Iris Apfel have drawn significant crowds to the Met. The Costume Institute's annual Benefit Gala, co-chaired by Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, is an extremely popular, if exclusive, event in the fashion world; in 2007, the 700 available tickets started at $6,500 per person.[26] Exhibits displayed over the past decade in the Costume Institute include: Rock Style, in 1999, representing the style of more than 40 rock musicians, including Madonna, David Bowie, and The Beatles; Extreme Beauty: The Body Transformed, in 2001, which exposes the transforming ideas of physical beauty over time and the bodily contortion necessary to accommodate such ideals and fashion; The Chanel Exhibit, displayed in 2005, acknowledging the skilled work of designer Coco Chanel as one of the leading fashion names in history; Superheroes: Fashion and Fantasy, exhibited in 2008, suggesting the metaphorical vision of superheroes as ultimate fashion icons; the 2010 exhibit on the American Woman: Fashioning a National Identity, which exposes the revolutionary styles of the American woman from the years 1890 to 1940, and how such styles reflect the political and social sentiments of the time. The theme of the 2011 event was "Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty". Each of these exhibits explores fashion as a mirror of cultural values and offers a glimpse into historical styles, emphasizing their evolution into today's own fashion world. On January 14, 2014, the Met named the Costume Institute complex after Anna Wintour.[27] The curator is Andrew Bolton.

The Costume Institute is known for throwing the annual Met Gala and for putting on blockbuster summer shows like Savage Beauty and China: Through the Looking Glass.[28][29][30]

Drawings and prints

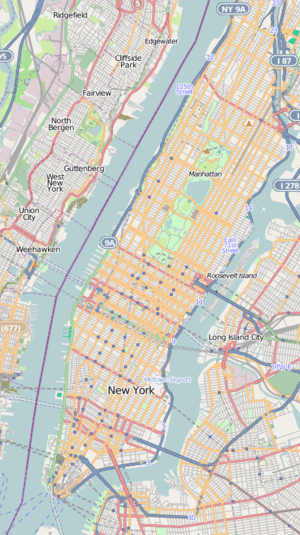

Though other departments contain significant numbers of drawings and prints, the Drawings and Prints department specifically concentrates on North American pieces and western European works produced after the Middle Ages. The first Old Master drawings, comprising 670 sheets, were presented as a single group in 1880 by Cornelius Vanderbilt II and in effect launched the department, though it was not formally constituted as a department until later. Other early donors to the department include Junius Spencer Morgan II who presented a broad range of material, but mainly dated from the sixteenth century, including 2 woodblocks and many prints by Albrecht Dürer in 1919. Currently, the Drawings and Prints collection contains more than 17,000 drawings, 1.5 million prints, and twelve thousand illustrated books.[31] The great masters of European painting, who produced many more sketches and drawings than actual paintings, are extensively represented in the Drawing and Prints collection. The department's holdings contain major drawings by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Rembrandt, as well as prints and etchings by Van Dyck, Dürer, and Degas among many others.

Egyptian art

Though the majority of the Met's initial holdings of Egyptian art came from private collections, items uncovered during the museum's own archeological excavations, carried out between 1906 and 1941, constitute almost half of the current collection. More than 26,000 separate pieces of Egyptian art from the Paleolithic era through the Ptolemaic era constitute the Met's Egyptian collection, and almost all of them are on display in the museum's massive wing of 40 Egyptian galleries.[32] Among the most valuable pieces in the Met's Egyptian collection are 13 wooden models (of the total 24 models found together, 12 models and 1 offering bearer figure is at the Met, while the remaining 10 models and 1 offering bearer figure are in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo), discovered in a tomb in the Southern Asasif in western Thebes in 1920. These models depict, in unparalleled detail, a cross-section of Egyptian life in the early Middle Kingdom: boats, gardens, and scenes of daily life are represented in miniature. William the Faience Hippopotamus is a miniature shown at right.

However, the popular centerpiece of the Egyptian Art department continues to be the Temple of Dendur. Dismantled by the Egyptian government to save it from rising waters caused by the building of the Aswan High Dam, the large sandstone temple was given to the United States in 1965 and assembled in the Met's Sackler Wing in 1978. Situated in a large room, partially surrounded by a reflecting pool and illuminated by a wall of windows opening onto Central Park, the Temple of Dendur is one of the Met's most enduring attractions.

The oldest items at the Met, a set of Archeulian flints from Deir el-Bahri which date from the Lower Paleolithic period (between 300,000 and 75,000 BC), are part of the Egyptian collection.

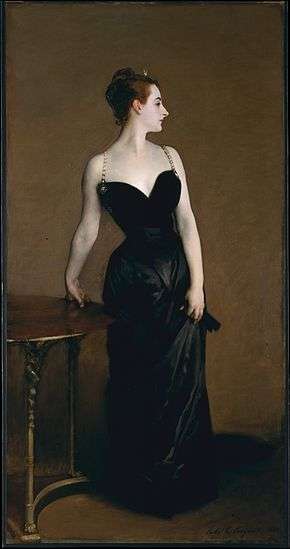

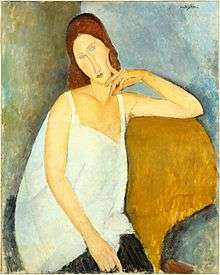

European paintings

The Met's collection of European paintings numbers around 1,700 pieces,[33] some of which are shown among the Selections from the permanent collection of paintings section, below.

European sculpture and decorative arts

The European Sculpture and Decorative Arts collection is one of the largest departments at the Met, holding in excess of 50,000 separate pieces from the 15th through the early 20th centuries.[34] Though the collection is particularly concentrated in Renaissance sculpture—much of which can be seen in situ surrounded by contemporary furnishings and decoration—it also contains comprehensive holdings of furniture, jewelry, glass and ceramic pieces, tapestries, textiles, and timepieces and mathematical instruments. In addition to its outstanding collections of English and French furniture, visitors can enter dozens of completely furnished period rooms, transplanted in their entirety into the Met's galleries. The collection even includes an entire 16th-century patio from the Spanish castle of Vélez Blanco, reconstructed in a two-story gallery, and the intarsia studiolo from the ducal palace at Gubbio. Sculptural highlights of the sprawling department include Bernini's Bacchanal, a cast of Rodin's The Burghers of Calais and several unique pieces by Houdon, including his Bust of Voltaire and his famous portrait of his daughter Sabine.

The American Wing

The Museum's collection of American art returned to view in new galleries on January 16, 2012. The new installation provides visitors with the history of American art from the 18th through the early 20th century. The new galleries encompasses 30,000 square feet for the display of the Museum's collection.[35]

Greek and Roman art

The Met's collection of Greek and Roman art contains more than 17,000 objects.[36] The Greek and Roman collection dates back to the founding of the museum—in fact, the museum's first accessioned object was a Roman sarcophagus, still currently on display. Though the collection naturally concentrates on items from ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, these historical regions represent a wide range of cultures and artistic styles, from classic Greek black-figure and red-figure vases to carved Roman tunic pins.

Highlights of the collection include the monumental Amathus sarcophagus and a magnificently detailed Etruscan chariot known as the "Monteleone chariot". The collection also contains many pieces from far earlier than the Greek or Roman empires—among the most remarkable are a collection of early Cycladic sculptures from the mid-third millennium BC, many so abstract as to seem almost modern. The Greek and Roman galleries also contain several large classical wall paintings and reliefs from different periods, including an entire reconstructed bedroom from a noble villa in Boscoreale, excavated after its entombment by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. In 2007, the Met's Greek and Roman galleries were expanded to approximately 60,000 square feet (6,000 m2), allowing the majority of the collection to be on permanent display.[37]

Islamic art

The Met's collection of Islamic art is not confined strictly to religious art, though a significant number of the objects in the Islamic collection were originally created for religious use or as decorative elements in mosques. Much of the 12,000 strong collection consists of secular items, including ceramics and textiles, from Islamic cultures ranging from Spain to North Africa to Central Asia.[38] The Islamic Art department's collection of miniature paintings from Iran and Mughal India are a highlight of the collection. Calligraphy both religious and secular is well represented in the Islamic Art department, from the official decrees of Suleiman the Magnificent to a number of Qur'an manuscripts reflecting different periods and styles of calligraphy. Modern calligraphic artists also used a word or phrase to convey a direct message, or they created compositions from the shapes of Arabic words. Others incorporated indecipherable cursive writing within the body of the work to evoke the illusion of writing.[39]

Islamic Arts galleries had been undergoing refurbishment since 2001 and were reopened on November 1, 2011, as the New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. Until that time, a narrow selection of items from the collection had been on temporary display throughout the museum. As with many other departments at the Met, the Islamic Art galleries contain many interior pieces, including the entire reconstructed Nur Al-Din Room from an early 18th-century house in Damascus. However, the museum has confirmed to the New York Post that it has withdrawn from public display all paintings depicting Muhammad and may not rehang those that were displayed in the Islamic gallery before the renovation.[40]

Robert Lehman Collection

On the death of banker Robert Lehman in 1969, his Foundation donated 2,600 works of art to the museum.[41] Housed in the "Robert Lehman Wing," the museum refers to the collection as "one of the most extraordinary private art collections ever assembled in the United States".[42] To emphasize the personal nature of the Robert Lehman Collection, the Met housed the collection in a special set of galleries which evoked the interior of Lehman's richly decorated townhouse; this intentional separation of the Collection as a "museum within the museum" met with mixed criticism and approval at the time, though the acquisition of the collection was seen as a coup for the Met.[43] Unlike other departments at the Met, the Robert Lehman collection does not concentrate on a specific style or period of art; rather, it reflects Lehman's personal interests. Lehman the collector concentrated heavily on paintings of the Italian Renaissance, particularly the Sienese school. Paintings in the collection include masterpieces by Botticelli and Domenico Veneziano, as well as works by a significant number of Spanish painters, El Greco and Goya among them. Lehman's collection of drawings by the Old Masters, featuring works by Rembrandt and Dürer, is particularly valuable for its breadth and quality.[44] Princeton University Press has documented the massive collection in a multi-volume book series published as The Robert Lehman Collection Catalogues.

Medieval art and the Cloisters

The Met's collection of medieval art consists of a comprehensive range of Western art from the 4th through the early 16th centuries, as well as Byzantine and pre-medieval European antiquities not included in the Ancient Greek and Roman collection. Like the Islamic collection, the Medieval collection contains a broad range of two- and three-dimensional art, with religious objects heavily represented. In total, the Medieval Art department's permanent collection numbers about 11,000 separate objects, divided between the main museum building on Fifth Avenue and The Cloisters.

Main building

The medieval collection in the main Metropolitan building, centered on the first-floor medieval gallery, contains about six thousand separate objects. While a great deal of European medieval art is on display in these galleries, most of the European pieces are concentrated at the Cloisters (see below). However, this allows the main galleries to display much of the Met's Byzantine art side-by-side with European pieces. The main gallery is host to a wide range of tapestries and church and funerary statuary, while side galleries display smaller works of precious metals and ivory, including reliquary pieces and secular items. The main gallery, with its high arched ceiling, also serves double duty as the annual site of the Met's elaborately decorated Christmas tree.

The Cloisters museum and gardens

The Cloisters was a principal project of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a major benefactor of the Met. Located in Fort Tryon Park and completed in 1938, it is a separate building dedicated solely to medieval art. The Cloisters collection was originally that of a separate museum, assembled by George Grey Barnard and acquired in toto by Rockefeller in 1925 as a gift to the Met.[45]

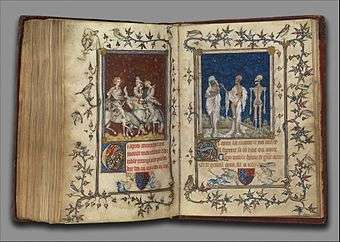

The Cloisters are so named on account of the five medieval French cloisters whose salvaged structures were incorporated into the modern building, and the five thousand objects at the Cloisters are strictly limited to medieval European works. The collection features items of outstanding beauty and historical importance; including the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry illustrated by the Limbourg Brothers in 1409, the Romanesque altar cross known as the "Cloisters Cross" or "Bury Cross", and the seven tapestries depicting the Hunt of the Unicorn.

Modern and contemporary art

With some 13,000 artworks, primarily by European and American artists, the modern art collection occupies 60,000 square feet (6,000 m2), of gallery space and contains many iconic modern works. Cornerstones of the collection include Picasso's portrait of Gertrude Stein, Jasper Johns's White Flag, Jackson Pollock's Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), and Max Beckmann's triptych Beginning. Certain artists are represented in remarkable depth, for a museum whose focus is not exclusively on modern art: for example, the collection contains forty paintings by Paul Klee, spanning his entire career. Due to the Met's long history, "contemporary" paintings acquired in years past have often migrated to other collections at the museum, particularly to the American and European Paintings departments.

In April 2013, it was reported that the Museum was to receive a collection worth $1 billion from cosmetics tycoon Leonard Lauder. The collection of Cubist art includes work by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris and went on display in 2014.[46]

Musical instruments

The Met's collection of musical instruments, with about 5,000 examples of musical instruments from all over the world, is virtually unique among major museums.[47] The collection began in 1889 with a donation of several hundred instruments by Lucy W. Drexel, but the department's current focus came through donations over the following years by Mary Elizabeth Adams, wife of John Crosby Brown. Instruments were (and continue to be) included in the collection not only on aesthetic grounds, but also insofar as they embodied technical and social aspects of their cultures of origin. The modern Musical Instruments collection is encyclopedic in scope; every continent is represented at virtually every stage of its musical life. Highlights of the department's collection include several Stradivari violins, a collection of Asian instruments made from precious metals, and the oldest surviving piano, a 1720 model by Bartolomeo Cristofori. Many of the instruments in the collection are playable, and the department encourages their use by holding concerts and demonstrations by guest musicians.

Photographs

The Met's collection of photographs, numbering more than 25,000 in total,[48] is centered on five major collections plus additional acquisitions by the museum. Alfred Stieglitz, a famous photographer himself, donated the first major collection of photographs to the museum, which included a comprehensive survey of Photo-Secessionist works, a rich set of master prints by Edward Steichen, and an outstanding collection of Stieglitz's photographs from his own studio. The Met supplemented Stieglitz's gift with the 8,500-piece Gilman Paper Company Collection, the Rubel Collection, and the Ford Motor Company Collection, which respectively provided the collection with early French and American photography, early British photography, and post-WWI American and European photography. The museum also acquired Walker Evans's personal collection of photographs, a particular coup considering the high demand for his works. The department of photography was founded in 1992. Though the department gained a permanent gallery in 1997, not all of the department's holdings are on display at any given time, due to the sensitive materials represented in the photography collection. However, the Photographs department has produced some of the best-received temporary exhibits in the Met's recent past, including a Diane Arbus retrospective and an extensive show devoted to spirit photography. In 2007, the museum designated a gallery exclusively for the exhibition of photographs made after 1960.[49]

Met Breuer

On March 18, 2016, the museum opened a new venue in the Marcel Breuer-designed building at Madison Avenue and 75th Street in Manhattan's Upper East Side, the former Whitney Museum of American Art.[50] It extends the museum's modern and contemporary art program.[51]

Libraries

Each Department maintains a library, most of the material of which can be requested online through the libraries' catalog.[52]

There are two libraries that can be accessed without appointment:

Thomas J. Watson Library

The Thomas J. Watson Library is the central library of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and supports the activities of staff and researchers. Watson Library's collection contains approximately 900,000 volumes, including monographs and exhibition catalogs; over 11,000 periodical titles; and more than 125,000 auction and sale catalogs.[53] The Library includes a reference collection, auction and sale catalogs, a rare book collection, manuscript items, and vertical file collections. The Library is accessible to anyone 18 years of age or older simply by registering online and providing a valid photo ID.[54]

Nolen Library

The Nolen Library is open to the general public. The collection of some 8,000 items, arranged in open shelves, includes books, picture books, DVDs, and videos. The Nolen Library includes a children's reading room and materials for teachers.[55]

Special exhibitions

The museum regularly hosts notable special exhibitions, often focusing on the works of one artist that have been loaned out from a variety of other museums and sources for the duration of the exhibition. These exhibitions are part of the attraction that draw people both within and outside Manhattan to explore the Met. Such exhibitions include displays especially designed for the Costume Institute, paintings from artists from across the world, works of art related to specific art movements, and collections of historical artifacts. Exhibitions are commonly located within their specific departments, ranging from American decorative arts, arms and armor, drawings and prints, Egyptian art, Medieval art, musical instruments, and photographs. Typical exhibitions run for months at a time and are open to the general public. Each exhibition provides insight into the world of art as a transformative, cultural experience and often includes a historical analysis to demonstrate the profound impact that art has on society and its dramatic transformation over the years.[56]

History

The New York State Legislature granted the Metropolitan Museum of Art an Act of Incorporation on April 13, 1870 "for the purpose of establishing and maintaining in said City a Museum and Library of Art, of encouraging and developing the Study of the Fine Arts, and the application of Art to manufacture and natural life, of advancing the general knowledge of kindred subjects, and to that end of furnishing popular instruction and recreations".[57]

The museum first opened on February 20, 1872, housed in a building located at 681 Fifth Avenue in New York City. John Taylor Johnston, a railroad executive whose personal art collection seeded the museum, served as its first president, and the publisher George Palmer Putnam came on board as its founding superintendent. The artist Eastman Johnson acted as co-founder of the museum.[58] Various other industrialists of the age served as co-founders, including Howard Potter. The former Civil War officer, Luigi Palma di Cesnola, was named as its first director. He served from 1879 to 1904. Under their guidance, the Met's holdings, initially consisting of a Roman stone sarcophagus and 174 mostly European paintings, quickly outgrew the available space. In 1873, occasioned by the Met's purchase of the Cesnola Collection of Cypriot antiquities, the museum decamped from Fifth Avenue and took up residence at the Mrs. Nicholas Cruger Mansion also known as the Douglas Mansion (James Renwick, 1853–54, demolished) at 128 West 14th Street. However, these new accommodations proved temporary, as the growing collection required more space than the mansion could provide.[59]

Between 1879 and 1895, the Museum created and operated a series of educational programs, known as the Metropolitan Museum of Art Schools, intended to provide vocational training and classes on fine arts.[60]

The museum celebrated its 75th anniversary (which it termed Diamond Jubilee) with a variety of programs, initiatives, and events in 1946, culminating in the anniversary of the opening of its first exhibition on February 22, 1947. The anniversary festivities included speeches, exhibitions, cross-promotions with films and plays, and related displays in Fifth Avenue store windows. The celebration also included membership drive and a fundraising campaign to support a planned renovation and expansion of the Central Park building under the chairmanship of the Museum's Vice President Thomas J. Watson. Initial plans, which were not realized, included the creation of five separate museums within the new physical space, including amalgamation of the Whitney Museum of American Art into the Metropolitan Museum.[61]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial was celebrated with exhibitions, symposia, concerts, lectures, the reopening of refurbished galleries, special tours, social events, and other programming for eighteen months from October 1969 through the spring of 1971. The centennial's events (including an open house, Centennial Ball, year-long art history course for the public, and various educational programming and traveling exhibitions) and publications drew on support from prominent New Yorkers, artists, writers, composers, interior designers, and art historians.[62]

Architecture

After negotiations with the City of New York in 1871, the Met was granted the land between the East Park Drive, Fifth Avenue, and the 79th and 85th Street Transverse Roads in Central Park. A red-brick and stone "mausoleum" was designed by American architect Calvert Vaux and his collaborator Jacob Wrey Mould. Vaux's ambitious building was not well received; the building's High Victorian Gothic style being already dated prior to completion, and the president of the Met termed the project "a mistake."[63] Within 20 years, a new architectural plan engulfing the Vaux building was already being executed. Since that time, many additions have been made including the distinctive Beaux-Arts Fifth Avenue facade, Great Hall, and Grand Stairway. These were designed by architect and Met trustee Richard Morris Hunt, but completed by his son, Richard Howland Hunt in 1902 after his father's death.[64] The architectural sculpture on the facade is by Karl Bitter.[65]

.jpg)

The wings that completed the Fifth Avenue facade in the 1910s were designed by the firm of McKim, Mead & White. The modernistic glass sides and rear of the museum are the work of Roche-Dinkeloo. Kevin Roche has been the architect for the master plan and expansion of the museum for the past 42 years. He is responsible for designing all of its new wings and renovations including but not limited to the American Wing, Greek and Roman Court, and recently opened Islamic Wing.[66]

As of 2010, the Met measures almost 1⁄4-mile (400 m) long and with more than 2,000,000 square feet (190,000 m2) of floor space, more than 20 times the size of the original 1880 building.[67] The museum building is an accretion of over 20 structures, most of which are not visible from the exterior. The City of New York owns the museum building and contributes utilities, heat, and some of the cost of guardianship.

The Charles Engelhard Court of the American Wing features the facade of the Branch Bank of the United States, a Wall Street bank that was facing demolition in 1913.[68][69]

Roof garden

The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden is located on the roof near the southwestern corner of the museum. The garden's cafe and bar is a popular museum spot during the mild-weathered months, especially on Friday and Saturday evenings when large crowds can lead to long lines at the elevators. The roof garden offers views of Central Park and the Manhattan skyline.[70][71] The garden is the gift of philanthropists Iris and B. Gerald Cantor, founder and chairman of securities firm Cantor Fitzgerald.[72] The garden was opened to the public on August 1, 1987.[73]

Every summer since 1998 the roof garden has hosted a single-artist exhibition.[71] The artists have been: Ellsworth Kelly (1998), Magdalena Abakanowicz (1999), David Smith (2000), Joel Shapiro (2001), Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen (2002), Roy Lichtenstein (2003), Andy Goldsworthy (2004), Sol LeWitt (2005), Cai Guo-Qiang (2006), Frank Stella (2007), Jeff Koons (2008), Roxy Paine (2009) and Big Bambú by Doug and Mike Starn (2010).[74]

The roof garden offers "spectacular" views of the Manhattan skyline from a vantage point high above Central Park.[75] The views have been described as "the best in Manhattan."[76] Art critics have been known to complain that the view "distracts" from the art on exhibition.[77] New York Times art critic Ken Johnson complains that the "breathtaking, panoramic views of Central Park and the Manhattan skyline" creates "an inhospitable site for sculpture" that "discourages careful, contemplative looking."[78] Writer Mindy Aloff describes the roof garden as "the loveliest airborne space I know of in New York."[79]

The cafe and bar in this garden are considered romantic by many.[75][80][81]

Selected objects

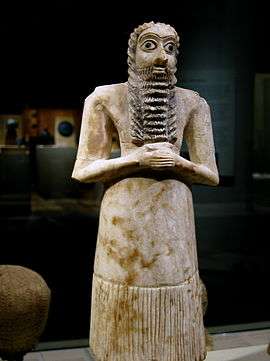

-

Standing male worshiper, Mesopotamian, 2750-2600 BC(?)

-

Sphinx, c 530 BC

-

Busto de Anicia Iuliana, Roman

-

Roman c 430

-

Book Cover with Byzantine Icon of the Crucifixion, before 1085

-

Tabernacle of Cherves, ca. 1220–1230

-

Spanish Processional Cross, late 11th–early 12th century, Asturias

-

Khatchkar. Basalt

-

Scuola di biduino, portale da san leonardo al frigido, vicino massa carrara, c. 1170-80

-

Tomb of Ermengol IX of Urgell (died 1243)

-

Enthroned Virgin and Child, c 1300, England

-

The Crucified Christ, c. 1300, Northern Europe

-

Attributed to Jean de Touyl (French, died 1349), Reliquary Shrine from the convent of the Poor Clares at Buda

-

Attributed to Jean Le Noir or follower, Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg, 14th-c illuminated manuscript

-

Doorway in granite, in oak, France, Limousin, 15th c, Aixe sur Vienne

-

Andrea da Giona, Altarpiece with Christ in Majesty, c 1434

-

Schwaben, c. 1489

-

Jain Shvetambara Tirthankara in Meditation, Solanki period, India, c. 1000-1050 CE

Selected paintings

-

Robert Campin, Triptych with the Annunciation, known as the Mérode Altarpiece", c. 1425–1428

-

Jan van Eyck, Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych, c. 1430–40

-

Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Lady, c. 1450, Florence

-

Caravaggio, The Musicians, 1595

-

El Greco, View of Toledo, 1596

-

.jpg)

El Greco, Opening of the Fifth Seal 1608–1614

-

Georges de La Tour, The Fortune Teller, c.1630

-

Rembrandt, Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer, 1653

-

Marie-Denise Villers, Young Woman Drawing, 1801

-

Francisco Goya, Majas on a Balcony, 1835

-

J.M.W. Turner, The Grand Canal, 1835

-

.jpg)

Thomas Cole, The Oxbow, 1836

-

Eugène Delacroix, Christ Asleep during the Tempest, 1853

-

Rosa Bonheur, The Horse Fair, 1853–1855

-

Édouard Manet, The Dead Christ with Angels, 1864

-

Edgar Degas, The Dancing Class, 1872

-

Édouard Manet, Boating 1874

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Mme. Charpentier and Her Children, 1878

-

Jules Bastien-Lepage, Jeanne d'Arc (Joan of Arc), 1879

-

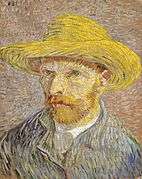

Vincent van Gogh, Cypresses,1889

-

_in_a_Red_Dress%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_116.5_x_89.5_cm%2C_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art%2C_New_York.jpg)

Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne (Hortense Fiquet, 1850–1922) in a Red Dress, 1888–90

-

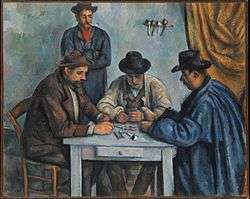

Paul Cézanne, The Card Players, 1890–1892

-

Claude Monet, The Four Trees, (Four Poplars on the Banks of the Epte River near Giverny), 1891

-

Paul Gauguin, The Midday Nap, 1894

-

Winslow Homer, The Gulf Stream, 1899

-

Claude Monet, The Houses of Parliament (Effect of Fog), 1903–1904

-

Pablo Picasso, l'Acteur (The Actor), 1904–05

-

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Gertrude Stein, 1906

-

Henri Matisse, The Young Sailor II, 1906

-

Henri Rousseau, The Repast of the Lion, c. 1907

-

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_81_x_54.1_cm%2C_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art.jpg)

Georges Braque, Still Life with Mandola and Metronome, late 1909

-

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_38.1_x_45.7_cm_(15_x_18_in.)%2C_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art.jpg)

Pablo Picasso, The Oil Mill (Moulin à huile), 1909

-

Pablo Picasso, Still Life with a Bottle of Rum, 1911

-

Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation 27, Garden of Love II, 1912 (exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show)

-

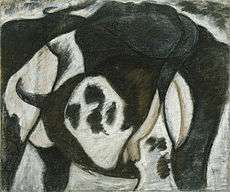

Arthur Dove, Cow, 1914

Management

Governance

The collections are owned by a private corporation of fellows and benefactors which totals about 950 persons. The museum is governed by a board of trustees of 41 elected members, several officials of the City of New York, and persons honored as trustees by the museum. The current chairman of the board, Daniel Brodsky was elected in 2011.[82] Other notable trustees include Anna Wintour, Richard Chilton, Alejandro Santo Domingo[83] as well as Mayor Bill de Blasio and his appointee Ken Sunshine.[84] On March 10, 2015, the Board of trustees chose Daniel Weiss, now President of Haverford College, to be the next President and Chief Operating Officer of the Met, replacing Emily K. Rafferty, who served in that role for a decade.[85] The 2009–10 operating budget was $221 million.

Finances

The museum's endowment is $2–3 billion and provides much of the income for operations while admissions account for only 15 percent.[86] Although the museum recommends an admission price of $25, visitors can pay what they wish to enter. This 1970 agreement between the museum and the city of New York requires visitors to pay at least a nominal amount; a penny is acceptable.[87]

The Met is reported to have the best credit rating by far of all major museums in the United States. This was last affirmed by Moody's in 2009, even after the agency assumed "a 30% reduction from investment losses and endowment spending" in the context of the late-2000s financial crisis. The museum fundraised $138 million in 2008.

Attendance

In 2016, the museum set a record for attendance, attracting 6.7 million visitors — the highest number since the museum began tracking admissions.[88] Forty percent of the Met’s visitors in fiscal year 2016 came from New York City and the tristate area; 41 percent from 190 countries besides the United States.[88]

Acquisitions and deaccessioning

The Metropolitan Museum of Art spent $39 million to acquire art for the fiscal year ending in June 2012.[89] At the same time, the museum is required to list in its annual report the total cash proceeds from art sales each year and to itemize any deaccessioned objects valued at more than $50,000 each. It must also sell those pieces at auction and provide advance public notice of a work being sold if it has been on view in the last ten years. These rules were imposed by the New York State Attorney General in 1972.[90]

During the 1970s, under the directorship of Thomas Hoving, the Met revised its deaccessioning policy. Under the new policy, the Met set its sights on acquiring "world-class" pieces, regularly funding the purchases by selling mid- to high-value items from its collection.[43] Though the Met had always sold duplicate or minor items from its collection to fund the acquisition of new pieces, the Met's new policy was significantly more aggressive and wide-ranging than before, and allowed the deaccessioning of items with higher values which would normally have precluded their sale. The new policy provoked a great deal of criticism (in particular, from The New York Times) but had its intended effect.[90]

Many of the items then purchased with funds generated by the more liberal deaccessioning policy are now considered the "stars" of the Met's collection, including Diego Velázquez's Juan de Pareja and the Euphronios krater depicting the death of Sarpedon (which has since been repatriated to the Republic of Italy). In the years since the Met began its new deaccessioning policy, other museums have begun to emulate it with aggressive deaccessioning programs of their own.[91] The Met has continued the policy in recent years, selling such valuable pieces as Edward Steichen's 1904 photograph The Pond-Moonlight (of which another copy was already in the Met's collection) for a record price of $2.9 million.[92]

Controversies

Acquisition of looted and stolen antiquities

One of the most serious challenges to the Metropolitan Museum's reputation has been a series of allegations and lawsuits about its status as an institutional buyer of looted and stolen antiquities. Since the 1990s the Met has been the subject of numerous investigative reports and books critical of the Met's laissez-faire attitude to acquisition.[93][94] The Met has lost several major lawsuits, notably against the governments of Italy and Turkey, who successfully sought the repatriation of hundreds of ancient Mediterranean and Middle Eastern antiquities, with a total value in the hundreds of millions of dollars.[93]

In the late 1990s, long-running investigations by the Tutela del Patrimonio Culturale (TPC), the art crimes division of the Italian Carabinieri, accused the Metropolitan Museum of acquiring "black market" antiquities. TPC investigations in Italy revealed that many ancient Mediterranean objects acquired from the 1960s to the 1990s had been purchased, via a complex network of front companies and unscrupulous dealers, from the criminal gang led by Italian art dealer Giacomo Medici."[93] The Met is also one of many institutional buyers known to have acquired looted artifacts from a Thai-based British "collector", Douglas Latchford."[95] In 2013, the Met announced that it would repatriate to Cambodia two ancient Khmer statues, known as "The Kneeling Attendants" , which it had acquired from Latchford (in fragments) in 1987 and 1992. A spokesperson for the Met stated that the museum had received "dispositive" evidence that the objects had been looted from Koh Ker and illegally exported to the USA.[96]

In addition to the ongoing investigations by the Italian police (TPC), lawsuits brought by the Governments of Italy, Turkey and Cambodia against the Metropolitan Museum of Art contend that the acquisition of the Euphronius krater may have demonstrated a pattern of less than rigorous investigation into the origin and legitimate provenance of highly desirable antiquities for the Museum's collections. Examples include, the Cloisters Cross, a large Romanesque cross carved from walrus ivory,[93] the Karun Treasure, also known as the Lydian Hoard, a collection of 200 gold, silver, bronze and earthenware objects, dating from the 7th Century BCE, and part of a larger haul of some 450 objects looted by local tomb robbers from four ancient royal tombs near Sardis, in Turkey in 1966-67.[97] After a six-year legal battle that reportedly cost the Turkish government UK£25 million[98] the case ended dramatically after it was revealed that the minutes of the Met's own acquisition committee described how a curator had actually visited the looted burial mounds in Turkey to confirm the authenticity of the objects. The Met was forced to concede that staff had known the objects were stolen when it bought them, and the collection was repatriated to Turkey in 1993.[93]

The Morgantina treasure is a hoard of ornate Hellenistic silverware dated 3rd century BC, valued at perhaps up to US$100 million, acquired by the Met in the early 1980s. It was later shown to have been looted from the Morgantina archaeological site in Sicily. After a protracted lawsuit, the Met conceded that it was looted, and agreed in 2006 to repatriate it to Sicily, with the Met stating in 2006 that the repatriation "redresses past improprieties in the acquisitions process".[93][99]

Other controversies

In 1969, an exhibit titled "Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968" provoked boycotts even before opening due to the museum's decision to "exclude Harlemites from participating in the exhibition planning and to exclude artwork by Harlem's thriving artist community from the exhibition. The museum justified this decision by arguing [that] Harlem itself was a work of art and the inclusion of artworks in Harlem on My Mind would only detract from the overall exhibition".[100] Norman Lewis, Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, Clifford Joseph, Roy DeCarava, Reginald Gammon, Henri Ghent, Raymond Saunders, and Alice Neel were among the artists who picketed the show.[101]

The book Rogues' Gallery by the journalist Michael Gross was published in May 2009 focusing on the personalities behind the museum, showcasing their personal peccadilloes, charting the relationship between the public and private behavior and ambitions of its trustees and benefactors and their cultural philanthropy. A museum spokesman condemned the book as "misleading" and "insensitive",[102] and the museum bookstore declined to sell it.[103] The New York Times Book Review noted that the subjects of the book "form a blockbuster exhibition of human achievement and flaws," but ultimately criticized the book's focus on "lurid" matters unrelated to art.[104]

References

Notes

- ↑ "Today in Met History: April 13". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- 1 2 "The Metropolitan Museum of Art: About". Artinfo. 2008. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- 1 2 "Brief History of The Museum". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ↑ "Exhibition and museum attendance figures 2009" (PDF). The Art Newspaper. London. April 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ↑ Davidson, Justin (February 17, 2016). "The Metropolitan Museum of Art's New Logo Is a Typographic Bus Crash". Vulture. Retrieved 10 March 2016. Both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Opera, also in New York, are nicknamed "The Met"

- ↑ Lande, Nathaniel; Lande, Andrew (3 April 2012). Top 10 Museums and Galleries. The 10 Best of Everything, Third Edition. National Geographic Society. p. 90. ISBN 978-1426208676.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Museum Launches New and Expanded Web Site", press release, The Met, January 25, 2000

- 1 2 "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Curatorial Departments". Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ↑ "Visit The Cloisters". Retrieved 2012-02-18.

- 1 2 de Montebello, Philippe (1997). Masterpieces of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0-300-10615-7.

- 1 2 Pyhrr, Stuart W. (2003). Arms and Armor: Notable Acquisitions 1991–2002 – The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-300-09876-6.

- 1 2 Peck, Amelia (1996). Period Rooms in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 17,275. ISBN 0-300-10522-3.

- ↑ Moske, James. "This Weekend in Met History: February 20". Museum Archives. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Miriam Kreinin Souccar (2008-09-10). "New Met Director has Lots of Company". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ Kelly Crow (2008-09-10). "Met Selects Curator to Run Museum". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Ancient Near Eastern Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "Assyria, 1365–609 B.C. | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Arms and Armor". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Ezra, Kate (1992). Royal Art of Benin – The Perls Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-632-0.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Asian Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "1944". Playbill. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

Philanthropist Irene Lewisohn died today in New York City. She and her sister Alice built and endowed the Neighborhood Playhouse. With Aline Bernstein she founded the Museum of Costume Art on Fifth Avenue in 1937.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – The Costume Institute". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Postrel, Virginia (May 2007). "Dress Sense". The Atlantic. p. 133.

- ↑ Karimzadeh, Marc (14 January 2014). "Met Names Costume Institute Complex in Honor of Anna Wintour". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ Bourne, Leah (May 5, 2011). "Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Met Gala (But Were Too Afraid To Ask)". NBC New York. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- ↑ Trebay, Guy (29 April 2015). "At the Met, Andrew Bolton Is the Storyteller in Chief". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Tomkins, Calvin (25 March 2013). "Anarchy Unleashed". The New Yorker. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Drawings and Prints". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Egyptian Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – European Paintings". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – European Sculpture and Decorative Arts". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "The New American Wing". metmuseum.org.

- ↑ Attributed to the Bastis Master. "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Greek and Roman Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael (2007-04-20). "Classical Treasures, Bathed in a New Light". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Islamic Art". Metmuseum.org. 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Mikdadi, Salwa (2000). "West Asia: Between Tradition and Modernity". New York: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History; The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Vincent, Isabel (10 January 2010). "'Jihad' jitters at Met". New York Post. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – The Robert Lehman Collection". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "The Robert Lehman Collection" (Press release). Metropolitan Museum of Art. September 1999. Archived from the original on February 12, 2006.

- 1 2 Hoving, Thomas (22 January 1993). Making the Mummies Dance. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0671738549. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Russell, John (February 18, 2000). "Art Review: Feast of Illuminations and Drawings". The New York Times.

- ↑ "The Cloisters Museum and Gardens". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Nolan, Steve. "Collection worth $1BILLION is donated to New York Metropolitan Museum of Art by cosmetics tycoon Leonard Lauder". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Musical Instruments". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Photographs". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Karen (September 28, 2007). "Modern Photography in a Brand-New Space". The New York Times.

- ↑ "A Look at the Met Breuer Before the Doors Open" by Randy Kennedy, The New York Times, March 1, 2016

- ↑ The Met Breuer, he Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ "The Met Libraries". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ "Collections".

- ↑ "Access Hours and Policies".

- ↑ "Libraries and Study Centers".

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Exhibitions". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Disturnell, John New York as it was and as it is, D. Van Nostrand, New York, 1876. "Metropolitan Museum of Art", p. 101.

- ↑ Eastman Johnson | Co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Gross, Michael (5 May 2009). Rogues' Gallery, The Secret History of the Moguls and the Money That Made the Metropolitan Museum. New York: Broadway Books. p. 45. ISBN 978-0767924887. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Finding aid for Schools of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Records (1879–1895). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ Finding aid for the Metropolitan Museum of Art 75th Anniversary Committee records, 1945–1950, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ George Trescher records related to The Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, 1949, 1960–1971 (bulk 1967–1970). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ Halford, Macy (December 1, 2008). "At the Museums: Four Eyes". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Gross, Michael, Rogues' Gallery, The Secret History of the Moguls and the Money That Made the Metropolitan Museum, Broadway Books, New York, 2009, p. 75.

- ↑ Schevill, Ferdinand, ‘Karl Bitter: A Biography”, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, 1917 p. ix

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Summer 1995)

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art at HumanitiesWeb". Humanitiesweb.org. 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Vogel, Carol (May 4, 2009). "The Met Offers a New Look at Americana". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ↑ Heckscher, Morrison H. (Summer 1995). "The Metropolitan Museum of Art: An Architectural History" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 54. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ↑ Nash, Eric Peter (1996). New York's 50 Best Secret Architectural Treasures. New York: City & Co. ISBN 978-1-885492-31-9.

- 1 2 Baron, James; Anna Quindlen (2009). The New York Times Book of New York: 549 Stories of the People, the Events, and the Life of the City—Past and Present. London: Black Dog Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57912-801-2.

- ↑ "Biography of B. Gerald Cantor". www.cantorfoundation.org. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ "New Roof Garden at Metropolitan Museum". The New York Times. June 4, 1987. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Doug and Mike Starn Create Monumental Sculpture for Metropolitan Museum's 2010 Roof Garden Installation; Big Bambú to Open April 27 April 27– October 31, 2010 (weather permitting)" (Press release). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. April 27, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- 1 2 Louie, Elaine (July 17, 1996). "A Sip and a View, Without the Grit". The New York Times. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Miller, Lori (August 2, 1987). "Met's Garden: Where Views Enhance Art". The New York Times. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Museum and Gallery Listings". The New York Times. May 16, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Johnson, Ken (April 22, 2008). "Art Review, A Panoramic Backdrop for Meaning and Mischief". The New York Times. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Aloff, Mindy (August 22, 1997). "Where to Cool Both Soul and Heels". The New York Times. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Bykofsky, Sheree; Arthur Schwart (2001). The 52 Most Romantic Dates in and Around New York City. Avon, Massachusetts: Adams Media. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-58062-462-6.

- ↑ Bennett, Bruce. "Nightlife: The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden". New York. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Taylor, Kate (May 5, 2011). "Daniel Brodsky is Voted Chairman of the Metropolitan Museum of Art". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Annual Report: Board of Trustees" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. November 1, 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Emily (September 13, 2014). "Ken Sunshine Joins the Met's Board of Trustees". New York Post.

- ↑ Kennedy, Randy (10 March 2015). "Metropolitan Museum of Art Names New President: Daniel Weiss". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ "Annual Report for the Year 2009–2010" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. November 9, 2010.

- ↑ "NYC art museum accused of duping visitors on admission fees". Associated Press/Fox News. 25 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- 1 2 Robin Pogrebin (August 4, 2016), The Metropolitan Museum of Art Announces Record Attendance New York Times.

- ↑ Robin Pogrebin (July 22, 2013), "Qatar Uses Its Riches to Buy Art Treasures", The New York Times.

- 1 2 Pogrebin, Robin (January 26, 2011). "The Permanent Collection May Not Be So Permanent". The New York Times.

- ↑ Bone, James (October 31, 2005). "Brimful museums put art under the hammer". The Times. London. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ "Rare photo sets $2.9m sales record". BBC News. 2006-02-15. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Peter Watson, Cecilia Todeschini (2007), The Medici Conspiracy: The Illicit Journey of Looted Antiquities from Italy's Tomb Raiders to the World's Greatest Museums

- ↑ Vernon Silver, The Lost Chalice: The Epic Hunt for a Priceless Masterpiece. Harper Collins Books, 2009. ISBN 978-0-06-188296-8

- ↑ Chasing Aphrodite. "The Kushan Buddhas: Nancy Wiener, Douglas Latchford and New Questions about Ancient Buddhas" (originally posted 1 February 2015)

- ↑ Jason Felch, "Metropolitan Museum says it will return Cambodian statues". Los Angeles Times, 3 May 2013

- ↑ "Gold hippocampus from Lydian Hoard found". The History Blog, 28 November 2012

- ↑ "King Croesus's golden brooch to be returned to Turkey".Constanze Letch, The Guardian, 26 November 2012

- ↑ Article, "Morgantina Silver", by Suzie Thomas, year 2012 at the website TraffickingCulture.org, website devoted to illicit trafficking in ancient art objects. The article cites the following press release issued by the Metropolitian Museum on 21 Feb 2006: "Statement by the Metropolitan Museum of Art on its agreement with the Italian Ministry of Culture".

- ↑ Cooks, Bridget R. (Spring 2007). "Black Artists and Activism: Harlem on My Mind (1969)". American Studies. 48 (1).

- ↑ Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. "Norman Lewis – First Major African American Abstract Expressionist". Violette de Mazia Foundation. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ↑ Pillifant, Reid (May 19, 2009). "Michael Gross Gets Lots of Dirty Looks But Little Buzz for Rogues' Gallery". The New York Observer. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ↑ Holterhoff, Manuela (May 14, 2009). "Secrets, Phonies Animate Lively Met Museum History: Interview". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ Finnerty, Amy (June 28, 2009). "Exhibitionists". The New York Times Book Review.

Bibliography

- Danziger, Danny (2007). Museum: Behind the Scenes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Viking, New-York City. ISBN 9780670038619.

- Howe, Winifred E., and Henry Watson Kent (2009). A History of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1. General Books, Memphis. ISBN 9781150535482.

- Tompkins, Calvin (1989). Merchants & Masterpieces: The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Henry Holt and Company, New York. ISBN 0805010343.

- Trask, Jeffrey (2012). Things American: Art Museums and Civic Culture in the Progressive Era. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. ISBN 9780812243628; A history that relates it the political context of the Progressive Era.

Further reading

- Vogel, Carol, "Grand Galleries for National Treasures", January 5; and Holland Cotter, "The Met Reimagines the American Story", review, January 15; two 2012 New York Times articles about American painting and sculpture galleries reopening after four-year renovation.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

- Official website

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art presents a Timeline of Art History

- Chronological list of special exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Digital Collections from the Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Watsonline: The Catalog of the Libraries of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Museum Libraries. "Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications". Digital Collections. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. (annual reports, collection catalogs, exhibit catalogs, etc.)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art NY

- Artwork owned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Coordinates: 40°46′44″N 73°57′49″W / 40.77891°N 73.96367°W