Outboard motor

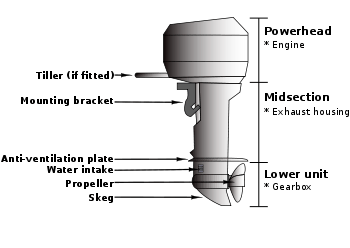

An outboard motor is a propulsion system for boats, consisting of a self-contained unit that includes engine, gearbox and propeller or jet drive, designed to be affixed to the outside of the transom. They are the most common motorized method of propelling small watercraft. As well as providing propulsion, outboards provide steering control, as they are designed to pivot over their mountings and thus control the direction of thrust. The skeg also acts as a rudder when the engine is not running. Unlike inboard motors, outboard motors can be easily removed for storage or repairs.

In order to eliminate the chances of hitting bottom with an outboard motor, the motor can be tilted up to an elevated position either electronically or manually. This helps when traveling through shallow waters where there may be debris that could potentially damage the motor as well as the propeller. If the electric motor required to move the pistons which raise or lower the engine is malfunctioning, every outboard motor is equipped with a manual piston release which will allow the operator to drop the motor down to its lowest setting.[1]

General uses

Large Outboards

Large outboards are usually bolted to the transom (or to a bracket bolted to the transom), and are linked to controls at the helm. These range from 2-, 3- and 4-cylinder models generating 15 to 135 horsepower suitable for hulls up to 17 feet (5.2 m) in length, to powerful V6 and V8 cylinder blocks rated up to 557 hp (415 kW).,[2] with sufficient power to be used on boats of 37 feet (11 m) or longer.

Portable

Small outboard motors, up to 15 horsepower or so are easily portable. They are affixed to the boat via clamps, and thus easily moved from boat to boat. These motors typically use a manual start system, with throttle and gearshift controls mounted on the body of the motor, and a tiller for steering. The smallest of these weigh as little as 12 kilograms (26 lb), have integral fuel tanks, and provide sufficient power to move a small dinghy at around 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) This type of motor is typically used:

- to power small craft such as jon boats, dinghies, canoes, etc.

- to provide auxiliary power for sailboats,

- for trolling aboard larger craft, as small outboards are typically more efficient at trolling speeds. In this application, the motor is frequently installed on the transom alongside and connected to the primary outboard to enable helm steering. In addition many small motor manufacturers have began offering variants with power trim/tilt and electric starting functions so that they may be completely controlled remotely.

Electric-powered

Commonly referred to as "trolling motors" or "electric outboard motors", electric outboards are used

- on very small craft or on small lakes where gasoline motors are prohibited,

- as a secondary means of propulsion on larger craft, and

- as repositioning thrusters while fishing for bass and other freshwater species,

and any other application where their quietness, and ease of operation and zero emissions outweigh the speed and range deficiencies.

Pump-jet

Pump-jet propulsion is available as an option on most outboard motors. Although less efficient than an open propeller, they are particularly useful in applications where the ability to operate in very shallow water is important. They also eliminate the laceration dangers of an open propeller.

History and developments

The first known outboard motor was a small 5 kilogram (11 lb) electric unit designed around 1870 by Gustave Trouvé,[3] and patented in May 1880 (Patent N° 136,560).[4] Later about 25 petrol powered outboards may have been produced in 1896 by American Motors Co[3]—but neither of these two pioneering efforts appear to have had much impact.

The Waterman outboard engine appears to be the first real gasoline-powered outboard offered for sale.[5] Developed by Cameron Waterman,[6] a young Yale Engineering student, it was developed from 1903, with a patent application filed in 1905[7] Starting in 1906,[8][9] the company went on to make thousands of his "Porto-Motor"[10] units,[11] claiming 25,000 sales by 1914.[12] The inboard boat motor firm of Caille Motor Company of Detroit were instrumental in making the cylinder and engines.

The most successful early outboard motor,[11] was created by Norwegian-American inventor Ole Evinrude in 1909.[13] Between 1909 and 1912, Evinrude made thousands of his outboards and the three horse units were sold around the world. His Evinrude Outboard Co. was spun off to other owners, and he went on to success after starting the ELTO company to produce a two-cylinder motor - ELTO stood for Evinrude Light Twin Outboard. The 1920s were the first high-water mark for the outboard with Evinrude, Johnson, ELTO, Atwater Lockwood and dozens of other makers in the field.

Historically, a majority of outboards have been two-stroke powerheads fitted with a carburetor due to the design's inherent simplicity, reliability, low cost and light weight. Drawbacks include increased pollution, due to the high volume of unburned gasoline and oil in their exhaust, and louder noise.

Four stroke outboards

Although four stroke outboards have been sold since the late 1920s, particularly Roness and Sharland, in 1962 Homelite introduced a commercially viable four cycle outboard a 55-horsepower motor, based on the 4 cylinder Crosley automobile engine. This was called the Bearcat that was later purchased by Fischer-Pierce who are the makers of Boston Whaler for use in their boats because of their technical superiority and efficiency over two strokes. In the early 1980s Honda Motor Co. introduced its first four-stroke powerhead.[14] In 1984, Yamaha introduced their first four-stroke powerhead. These motors were only available in the smaller horsepower range. In 1990 Honda released 35 hp and 45 hp four-stroke models. They continued to lead in the development of four-stroke engines throughout the 1990s as US and European exhaust emissions regulations such as CARB (California Air Resources Board) led to the proliferation of four-stroke outboards. At first, North American manufacturers such as Mercury and OMC used engine technology from Japanese manufacturers such as Yamaha and Suzuki until they were able to develop their own four-stroke engine. The inherent advantages of four-stroke motors included: lower pollution (especially oil in the water), noise reduction, increase fuel economy, increased low end torque, and smoother operation.

Honda Marine Group, Mercury Marine, Mercury Racing, Nissan Marine, Suzuki Marine, Tohatsu Outboards, Yamaha Marine, and China Oshen-Hyfong marine have all developed new four-stroke engines. Some are carburetted, usually the smaller engines. The balance are electronically fuel-injected. Depending on the manufacturer, newer engines benefit from advanced technology such as multiple valves per cylinder, variable camshaft timing (Honda's VTEC), boosted low end torque (Honda's BLAST), 3-way cooling systems, and closed loop fuel injection. Mercury Verado four-strokes are unique in that they are supercharged.

Mercury Marine, Mercury Racing, Tohatsu, Yamaha Marine, Nissan and Evinrude each developed computer-controlled direct-injected two-stroke engines. Each brand boasts a different method of DI.

Fuel economy on both direct injected and four-stroke outboards measures from a 10 percent to 80 percent improvement, compared with conventional two-strokes. Depending on rpm and load at cruising speeds, figure on about a 30 percent mileage improvement.[15]

Outboard motor selection

It is important to select a motor that is a good match for the hull in terms of power and shaft length.

Power requirements

Overpowering is a dangerous condition that can lead to the transom accelerating past the rest of the vessel[16] and underpowering often results in a boat that is incapable of performing in the role for which it was acquired. Boats built in the U.S. have a Coast Guard Rating Plate which specifies the maximum recommended horsepower for the hull. A motor with less than 75% of the maximum will most likely result in unsatisfactory performance.

Shaft length

Outboard motor shaft lengths are standardized to fit 15-inch, 20-inch and 25-inch transoms. If the shaft is too long it will extend farther into the water than necessary creating drag, which will impair performance and fuel economy. If the shaft is too short, the motor will be prone to ventilation. Even worse, if the water intake ports on the lower unit are not sufficiently submerged, engine overheating is likely, which can result in severe damage.

General Dimensions

Different outboard engine brands require different transom dimensions and sizes, that affects performance and trim.

| Outboard Brand - Model | Transom Angle | Max Transom Thickness | Transom To Bulkhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yamaha - F350 | 12° | 712 mm | |

| Yamaha – F300 | 12° | 712 mm | |

| EVINRUDE – DE 300 | 14° | 68.58 mm | |

| EVINRUDE - G2 300 HP | 14° | ||

| SUZUKI – DF 300 AP | 14° | 81 mm | |

| MERCURY – 300 HP | 14° |

Operational issues

Motor mounting height

Motor height on the transom is an important factor in achieving optimal performance. The motor should be as high as possible without ventilating or loss of water pressure. This minimizes the effect of hydrodynamic drag while underway, allowing for greater speed. Generally, the antiventilation plate should be about the same height as, or up to two inches higher than, the keel, with the motor in neutral trim.

Trim

Trim is the angle of the motor in relation to the hull, as illustrated below. The ideal trim angle is the one in which the boat rides level, with most of the hull on the surface instead of plowing through the water.

If the motor is trimmed out too far, the bow will ride too high in the water. With too little trim, the bow rides too low. The optimal trim setting will vary depending on many factors including speed, hull design, weight and balance, and conditions on the water (wind and waves). Many large outboards are equipped with power trim, an electric motor on the mounting bracket, with a switch at the helm that enables the operator to adjust the trim angle on the fly. In this case, the motor should be trimmed fully in to start, and trimmed out (with an eye on the tachometer) as the boat gains momentum, until it reaches the point just before ventilation begins or further trim adjustment results in an RPM increase with no increase in speed. Motors not equipped with power trim are manually adjustable using a pin called a topper tilt lock.

Ventilation

Ventilation is a phenomenon that occurs when surface air or exhaust gas (in the case of motors equipped with through-hub exhaust) is drawn into the spinning propeller blades. With the propeller pushing mostly air instead of water, the load on the engine is greatly reduced, causing the engine to race and the propeller to spin fast enough to result in cavitation, at which point little thrust is generated at all. The condition continues until the prop slows enough for the air bubbles to rise to the surface.[17] The primary causes of ventilation are: motor mounted too high, motor trimmed out excessively, damage to the antiventilation plate, damage to propeller, foreign object lodged in the diffuser ring.

Safety

If the helmsman goes overboard, the boat may continue under power but uncontrolled, risking serious or fatal injuries to the helmsman and others in the water. A safety measure is a "kill cord" attached to the boat and helmsman, which cuts the motor if the helmsman falls overboard.[18]

Cooling System

The most common type of cooling used on outboards of all eras use a rubber impeller to pump water from below the waterline up into the engine. This design has remained the standard due mainly to the efficiency and simplicity of its design. One disadvantage to this system is that if the impeller is run dry for a length of time (such as leaving the engine running when pulling the boat out of the water or in some cases tilting the engine out of the water while running), the impeller is likely to be ruined in the process.

Air cooled outboards

Air cooled outboard engines are currently produced by some manufacturers, these tend to be small engines of less than 5 horsepower. Outboard engines made by Briggs & Stratton are air-cooled[19]

Closed loop cooling

Outboards manufactured by Seven Marine use a closed-loop cooling system with heat exchanger. This means saltwater is not pumped through the engine block as is the case with most outboards but still has to be pumped through the heat exchanger

Other Outboard Motoring Method

In Vietnam and perhaps other parts of South East Asia such as Thailand, designs perhaps adapted from the predecessors of one such as this Kohler Long Tail,[20] using locally materials are used until the present. In Vietnam, they are called "May Duoi Tom"(Shrimp Tail Motor). The outboard motors, which can be smallish air-cooled or water-cooled gasoline, diesel or even modified automotive engines, are bolted to a welded steel tube frame, with another long steel tube up to 3 m long to hold the drive shaft, driving a conventional looking propeller. The frame that holds the motor has a short, swiveling steel pin/tube approximately 15 cm long underneath, to be inserted into a corresponding hole on the transom, or a solid block or wood purposely built-in thereof.,[21][22][23][24][25] This drop-in arrangement enables extremely quick transfer of the motor to another boat or for storage - all that is needed is to lift it out. The pivoting design allows the outboard motor to be swiveled by the operator in almost all directions: Sideways for direction, up and down to change the thrust line according to speed or bow lift, elevate completely out of water for easy starting, placing the drive shaft and the propeller forward along the side of the boat for reverse, or put them inside the boat for propeller replacement, which can be a regular occurrence to the cheap cast aluminum propellers on the often debris-prone inland waterways. This design is utilized to propel Long-tail boats.

Manufacturers

- Aquawatt Electric Outboard Motor

- Bolinder[26]

- Briggs & Stratton - USA - Up to 5 hp

- Cimco Marine AB

- DBD Marine

- ELTO

- ePropulsion - Hong Kong

- Evinrude/Johnson, a division of Bombardier Recreational Products - USA - Up to 300 hp

- Hidea - China

- Honda Marine Group - Japan - Up to 250 hp

- Kohler Company

- Jarvis Marine

- Maxus outboards

- Mud-skipper Longtail outboard

- McCulloch

- Mercury/Mariner - USA - Up to 300 hp

- Nissan Marine (now Tohatsu)

- Oshen-Hyfong Marine

- Parsun - China

- Selva Marine - Italy - Up to 250 hp

- Seven Marine - USA - One model of 557 hp, utilising General Motors powerplant

- Suzuki Marine - Japan - Up to 300 hp

- Tohatsu - Japan

- Tomos

- Torqeedo - Electric outboards

- Zomair

- Ul'yanovsk Motor Plant

- West Bend

- Yamaha Outboards - Japan - Up to 350 hp

Former manufacturers

- British Anzani

- British Seagull (defunct)

- Yanmar Diesel (no longer manufactures outboards)

See also

- Electric outboard motor

- Luxury yacht tenders

- Pneumatic motor

- Sterndrive (inboard/outboard drive)

References

- ↑ Wordford, Chris. "Outboard Motors". Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "Seven-Marine.com: "Seven Marine's 557 Horsepower V-8 Supercharged Outboard."". Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- 1 2 Olsson, Kent. "THE OUTBOARD MOTORS". Säffle Marinmotor Museum. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Desmond, Kevin. "A Brief History of Electric Water Speed Records". electric record team. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ "Kiekhaefer Will Fete Inventor of Outboard Motor", The Milwaukee Sentinel - Jan 16, 1955

- ↑ "Cameron Beach Waterman | Family Tree Unknown". wikitree.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "BOAT-PROPELLING DEVICBOAT-PROPELLING DEVICE", US Patent 851,389

- ↑ "The Original Outboard Motor", Bob Zipps, July 1988, The Antique Outboarder]

- ↑ "The History of Outboards", originally from: Bob Whittier, 1957, Yachting Magazine

- ↑ "Some early Porto-Motor advertisements", Rowboat Motor Journal, Vol 2, Issue 1, 2009

- 1 2 "The Outboard Motor Turns 100", boatingmag.com

- ↑ "Waterman PORTO Does It". The Independent. Jul 6, 1914. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ "Colorful rivalry of outboard giants ...", jsonline.com

- ↑ "Outboard Engines".

- ↑ "Two-Stroke versus Four-Stroke: Who's the Winner?". Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ↑ Standards for Backyard Boat Builders (COMTDPUB P16761.3B), United States Coast Guard, Summer 1993

- ↑ Carlton, John S., Marine Propellers and Propulsion, Elsevier, Ltd., 1994, ISBN 978-0-7506-8150-6

- ↑ "Royal Yachting Association: Use your kill cord, 30 April 2013". rya.org.uk. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Briggs & Stratton Outboard Motor Review". duckworksmagazine.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Gander Mountain® > Hunting, Fishing, Camping, and Outdoor Gear & Equipment : We Live Outdoors®". gandermountain.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Image: Mtchicvli.jpg, (768 × 512 px)". i1051.photobucket.com. 20 July 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Image: Mytutrngrtd.jpg, (768 × 512 px)". i1051.photobucket.com. 20 July 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ http://dantri.vcmedia.vn/Uploaded/2011/02/08/du-xuan-mien-Tay1.jpg

- ↑ "Image: 4476235603_a74f02303f.jpg, (500 × 289 px)". farm5.static.flickr.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Image: dealersite%2Fimages%2Fnewvehicles%2Fnv138300_0.jpg, (540 × 405 px)". images.psndealer.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ "Bolinder trim story". lagerholm.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Outboard motors. |

- "How A Kicker Works, June 1951, Popular Science by George W. Waltz Jr - one of the best basic articles on out board motors with lots of drawings and illustrations

- The Antique Outboard Motor Club International

- The Super-Elto Outboard Motor (1927) Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- The Antique Outboard Wiki

- Early Outboard Motor Boat Racing in British Columbia

Patents

- U.S. Patent 1,001,260 - Marine propulsion mechanism

- U.S. Patent 1,011,930 - Canoe and other small craft