Tauopathy

Not to be confused with Tautopathy, which is a controversial alternative medicine practice similar to Homeopathy.

| Tauopathy | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| MeSH | D024801 |

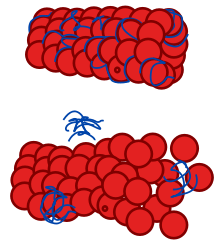

Tauopathies are a class of neurodegenerative diseases associated with the pathological aggregation of tau protein in neurofibrillary or gliofibrillary tangles[1] in the human brain. Tangles are formed by hyperphosphorylation of a microtubule-associated protein known as tau, causing it to aggregate in an insoluble form. (These aggregations of hyperphosphorylated tau protein are also referred to as paired helical filaments). The precise mechanism of tangle formation is not completely understood, and it is still controversial as to whether tangles are a primary causative factor in the disease or play a more peripheral role. Primary tauopathies, i.e., conditions in which neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) are predominantly observed, include:

- Primary age-related tauopathy (PART)/Neurofibrillary tangle-predominant senile dementia, with NFTs similar to AD, but without plaques.[2][3][4]

- Dementia pugilistica (chronic traumatic encephalopathy)[5]

- Progressive supranuclear palsy[6]

- Corticobasal degeneration

- Chronic traumatic encephalopathy[7]

- Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17[8]

- Lytico-Bodig disease (Parkinson-dementia complex of Guam)[9]

- Ganglioglioma and gangliocytoma[10]

- Meningioangiomatosis[11]

- Postencephalitic parkinsonism

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis[12]

- As well as lead encephalopathy, tuberous sclerosis, Hallervorden-Spatz disease, and lipofuscinosis[13]

Neurofibrillary tangles were first described by Alois Alzheimer in one of his patients suffering from Alzheimer's disease (AD), which is considered a secondary tauopathy. AD is also classified as an amyloidosis because of the presence of senile plaques.[2]

The degree of NFT involvement in AD is defined by Braak stages. Braak stages I and II are used when NFT involvement is confined mainly to the transentorhinal region of the brain, stages III and IV when there's also involvement of limbic regions such as the hippocampus, and V and VI when there's extensive neocortical involvement. This should not be confused with the degree of senile plaque involvement, which progresses differently.[14]

In Pick's disease and corticobasal degeneration tau proteins are deposited in the form of inclusion bodies within swollen or "ballooned" neurons.[15]

Argyrophilic grain disease (AGD), another type of dementia,[16][17][18] is marked by the presence of abundant argyrophilic grains and coiled bodies on microscopic examination of brain tissue.[19] Some consider it to be a type of Alzheimer disease.[19] It may co-exist with other tauopathies such as progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration,[2] and also Pick's disease.[20]

Huntington's disease: a neurodegenerative disease caused by a CAG tripled expansion in huntingtin gene is the most recently described tauopathy (Fernandez-Nogales et al. Nat Med 2014). JJ Lucas and co-workers demonstrated that in HD brains tau levels are increased and that the 4R/3R balance is altered. In addition, in this study, JJ Lucas shows intranuclear insoluble deposits of tau. These "Lucas' rods" were also found in Alzheimer's disease brains.

Tauopathies often have overlap with synucleinopathies, possibly because of interaction between the synuclein and tau proteins.[21][22]

The non-Alzheimer's tauopathies are sometimes grouped together as "Pick's complex" because of their association with Frontotemporal dementia, or Frontotemporal lobar degeneration.[23][24][25]

See also

References

- ↑ Rizzo, G.; Martinelli, P.; Manners, D.; Scaglione, C.; Tonon, C.; Cortelli, P.; Malucelli, E.; Capellari, S.; et al. (2008). "Diffusion-weighted brain imaging study of patients with clinical diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson's disease". Brain. 131 (Pt 10): 2690–700. doi:10.1093/brain/awn195. PMID 18819991.

- 1 2 3 Dickson, DW (2009). "Neuropathology of Non-Alzheimer Degenerative Disorders". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 3 (1): 1–23. PMC 2776269

. PMID 19918325.

. PMID 19918325. - ↑ Santa-Maria, Ismael; Haggiagi A; Liu X; Wasserscheid J; Nelson PT; Dewar K; Clark LN; Crary JF (Nov 2012). "The MAPT H1 haplotype is associated with tangle-predominant dementia". Acta Neuropathologica. 124 (5): 693–704. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-1017-1. PMID 22802095.

- ↑ Jellinger, K. A.; Attems, J. (2006). "Neurofibrillary tangle-predominant dementia: comparison with classical Alzheimer disease". Acta Neuropathologica. 113 (2): 107–17. doi:10.1007/s00401-006-0156-7. PMID 17089134.

- ↑ Roberts, GW (1988). "Immunocytochemistry of neurofibrillary tangles in dementia pugilistica and Alzheimer's disease: evidence for common genesis". Lancet. 2 (8626–8627): 1456–58. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90934-8. PMID 2904573.

- ↑ Williams, David R; Lees, Andrew J (2009). "Progressive supranuclear palsy: clinicopathological concepts and diagnostic challenges". The Lancet Neurology. 8 (3): 270–9. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70042-0. PMID 19233037.

- ↑ Mckee, Ann C.; Cairns, Nigel J. (2016). "The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy". Acta Neuropathologica. 131: 75–86. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1515-z. PMC 4698281

. PMID 26667418.

. PMID 26667418. - ↑ Selkoe, Dennis J.; Podlisny, Marcia B. (2002). "Deciphering the genetic basis of Alzheimer's disease". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 3: 67–99. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.3.022502.103022. PMID 12142353.

- ↑ Hof, P. R.; Nimchinsky, E. A.; Buée-Scherrer, V.; Buée, L.; Nasrallah, J.; Hottinger, A. F.; Purohit, D. P.; Loerzel, A. J.; et al. (1994). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/parkinsonism-dementia complex of Guam: quantitative neuropathology, immunohistochemical analysis of neuronal vulnerability, and comparison with related neurodegenerative disorders". Acta Neuropathologica. 88 (5): 397–404. doi:10.1007/BF00389490. PMID 7847067.

- ↑ Brat, Daniel J.; Gearing, Marla; Goldthwaite, Patricia T.; Wainer, Bruce H.; Burger, Peter C. (2001). "Tau-associated neuropathology in ganglion cell tumours increases with patient age but appears unrelated to ApoE genotype". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 27 (3): 197–205. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2990.2001.00311.x. PMID 11489139.

- ↑ Halper, J; Scheithauer, BW; Okazaki, H; Laws Jr, ER (1986). "Meningio-angiomatosis: a report of six cases with special reference to the occurrence of neurofibrillary tangles". Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 45 (4): 426–46. doi:10.1097/00005072-198607000-00005. PMID 3088216.

- ↑ Paula-Barbosa, M. M.; Brito, R.; Silva, C. A.; Faria, R.; Cruz, C. (1979). "Neurofibrillary changes in the cerebral cortex of a patient with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE)". Acta Neuropathologica. 48 (2): 157–60. doi:10.1007/BF00691159. PMID 506699.

- ↑ Wisniewski, Krystyna; Jervis, George A.; Moretz, Roger C.; Wisniewski, Henryk M. (1979). "Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles in diseases other than senile and presenile dementia". Annals of Neurology. 5 (3): 288–94. doi:10.1002/ana.410050311. PMID 156000.

- ↑ Braak, H.; Braak, E. (1991). "Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes". Acta Neuropathologica. 82 (4): 239–59. doi:10.1007/BF00308809. PMID 1759558.

- ↑ Arai, Tetsuaki; Ikeda, Kenji; Akiyama, Haruhiko; Shikamoto, Yasuo; Tsuchiya, Kuniaki; Yagishita, Saburo; Beach, Thomas; Rogers, Joseph; et al. (2001). "Distinct isoforms of tau aggregated in neurons and glial cells in brains of patients with Pick's disease, corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy". Acta Neuropathologica. 101 (2): 167–73. doi:10.1007/s004010000283 (inactive 2015-02-01). PMID 11271372.

- ↑ Ferrer I, Santpere G, van Leeuwen FW (2008). "Argyrophilic grain disease". Brain (journal). 131 (Pt 6): 1416–1432. doi:10.1093/brain/awm305. PMID 18234698.

- ↑ Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Parisi JE, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Geda YE, Jack CR Jr, Petersen RC, Dickson DW (2008). "Argyrophilic grains: a distinct disease or an additive pathology?". Neurobiology of Aging. 29 (4): 566–573. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.10.032. PMC 2727715

. PMID 17188783.

. PMID 17188783. - ↑ Wallon, D.; Sommervogel, C.; Laquerrière, A.; Martinaud, O.; Lecourtois, M.; Hannequin, D. (2010). "Maladie des grains argyrophiles : composante synergique de la démence ?" [Argyrophilic grain disease: synergistic component of dementia?]. Revue neurologique (in French). 166 (4): 428–32. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2009.10.012. PMID 19963233.

- 1 2 Tolnay, M; Monsch, AU; Staehelin, HB; Probst, A (1999). "Argyrophilic grain disease: differentiation from Alzheimer disease". Der Pathologe. 20 (3): 159–68. PMID 10412175.

- ↑ Jellinger KA (1998). "Dementia with grains (argyrophilic grain disease". Brain Pathology. 8 (2): 377–386. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00161.x. PMID 9546294.

- ↑ Simon Moussaud; Daryl R Jones; Elisabeth L Moussaud-Lamodière; Marion Delenclos; Owen A Ross & Pamela J McLean (corresponding author) (October 2014). "Alpha-synuclein and tau: teammates in neurodegeneration?". Mol Neurodegener. 9: 43. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-9-43. PMC 4230508

. PMID 25352339.

. PMID 25352339. - ↑ Jing L. Guo; Dustin J. Covell; Joshua P. Daniels; Michiyo Iba; Anna Stieber; Bin Zhang; Dawn M. Riddle; Linda K. Kwong; Yan Xu; John Q. Trojanowski & Virginia M.Y. Lee (July 2013). "Distinct α-Synuclein Strains Differentially Promote Tau Inclusions in Neurons". Cell. 154 (1): 103–17. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.057. PMC 3820001

. PMID 23827677.

. PMID 23827677. - ↑ Kertesz, Andrew (2003). "Pick Complex: An Integrative Approach to Frontotemporal Dementia". The Neurologist. 9 (6): 311–17. doi:10.1097/01.nrl.0000094943.84390.cf. PMID 14629785.

- ↑ Kertesz, Andrew (2003). "Pick's complex and FTDP-17". Movement Disorders. 18: 57–62. doi:10.1002/mds.10564.

- ↑ Andrew Kertesz; Paul McMonagle; Mervin Blair; Wilda Davidson; David G. Munoz (July 20, 2005). "The evolution and pathology of frontotemporal dementia". Brain. 128 (9): 1996–2005. doi:10.1093/brain/awh598. PMID 16033782.

External links

- Delacourte, A (2005). "Tauopathies: recent insights into old diseases". Folia Neuropathologica. 43 (4): 244–57. PMID 16416389.

- http://www.lifesci.sussex.ac.uk/home/Julian_Thorpe/ad_cyto.htm#tau

- Buée, L; Delacourte, A (1999). "Comparative biochemistry of tau in progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, FTDP-17 and Pick's disease". Brain Pathology. 9 (4): 681–93. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00550.x. PMID 10517507.