Plasma cell gingivitis

| Plasma cell gingivitis | |

|---|---|

| |

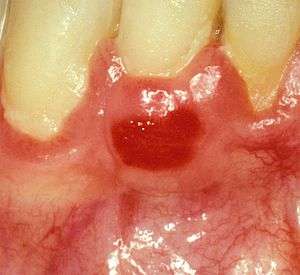

| Plasma cell gingivitis in an adult (histologically verified). | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | gastroenterology |

| ICD-10 | K13.0 (ILDS K13.060) |

Plasma cell gingivitis[1][2] is a rare condition,[3] appearing as generalized erythema (redness) and edema (swelling) of the attached gingiva, occasionally accompanied by cheilitis (lip swelling) or glossitis (tongue swelling).[4] It is called plasma cell gingivitis where the gingiva (gums) are involved,[5] plasma cell cheilitis,[5] where the lips are involved, and other terms such as plasma cell orifacial mucositis,[5] or plasma cell gingivostomatitis where several sites in the mouth are involved. On the lips, the condition appears as sharply outlined, infiltrated, dark red plaque with a lacquer-like glazing of the surface of the involved oral area.[5]

Classification

Depending upon the site of involvement, this condition could be considered a type of gingivitis (or gingival enlargement); a type of cheilitis; glossitis; or stomatitis. Sometimes the lips, the gums and the tongue can simultaneously be involved, and some authors have described this triad as a syndrome ("plasma-cell gingivostomatitis").[3] The mucous membranes of the genitals can also be involved by a similar condition, termed "plasma cell balanitis" [2] or "plasma cell vulvitis".[6]

Other synonyms for this condition not previously mentioned include atypical gingivitis, allergic gingivitis, plasmacytosis of the gingiva, idiopathic gingivostomatitis, and atypical gingivostomatitis.[3][7] Some of these terms are largely historical.

Plasma cell gingivits has been subclassified into 3 types based upon the cause; namely, allergic, neoplastic and of unknown cause.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Plasma cell gingivitis appears as mild gingival enlargement and may extend from the free marginal gingiva on to the attached gingiva.[8] Sometimes it is blended with a marginal, plaque induced gingivitis, or it does not involve the free marginal gingiva. It may also be found as a solitude red area within the attached gingiva (pictures). In some cases the healing of a plaque-induced gingivitis or a periodontitis resolves a plasma cell gingivitis situated a few mm from the earlier plack-infected marginal gingiva. In case of one or few solitary areas of plasma cell gingivitis, no symptoms are reported from the patient. Most often solitary entities are therefore found by the dentist.[2]

The gums are red, friable, or sometimes granular, and sometimes bleed easily if traumaticed.[8] The normal stippling is lost.[7] There is not usually any loss of periodontal attachment.[8] In a few cases a sore mouth can develop, and if so pain is sometimes made worse by toothpastes, or hot or spicy food.[7] The lesions can extend to involve the palate.[7]

Plasma cell cheilitis appears as well defined, infiltrated, dark red plaque with a superficial lacquer-like glazing.[5] Plasma cell cheilitis usually involves the lower lip.[3] The lips appear dry, atrophic and fissured.[7] Angular cheilitis is sometimes present.[7]

Where the condition involves the tongue, there is an erythematous enlargement with furrows, crenation and loss of the normal dorsal tongue coating.[7]

Causes

Plasma cell gingivits and plasma cell cheilitis are thought to be hypersensitivity reactions to some antigen.[3][8] Possible sources of antigens include ingredients in toothpastes, chewing gum, mints, pepper, or foods.[7][8] Specifically, cinnamonaldehyde and cinnamon flavoring are often to blame.[3] However, the exact cause in most is unknown.[3]

Diagnosis

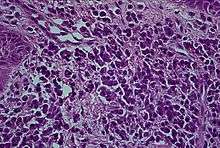

Histologically plasma cell gingivitis shows mainly plasma cells.[2] The differential diagnosis is with acute leukemia and multiple myeloma.[4] Hence, blood tests are often involved in ruling out other conditions.[3] A biopsy is usually taken, and allergy testing may also be used. The histopathologic appearance is characterized by diffuse, sub-epithelial plasma cell inflammatory infiltration into the connective tissue.[3] The epithelium shows spongiosis.[8] Some consider that plasmoacanthoma (solitary plasma cell tumor) is part of the same spectrum of disease as plasma cell cheilitis.[5]

Treatment

Preventing exposure to the causative antigen leads to resolution of the condition.[8] Tacrolimus or clobetasol propionate have also been used to treat plasma cell cheilitis.[5]

Epidemiology

Plasma cell gingivits is rare, and plasma cell cheilitis is very rare.[3] Most people with plasma cell cheilitis have been elderly.[3]

History

Plasma cell gingivitis was first described in the late 1960-early 1970s. A wave of cases occurred during this period, thought to be caused by allergic reactions to a component in chewing gum. Since, the number of cases has decreased, but they are still occasionally reported.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Glauser RO, Humpreys PK, Stanley HR, Baer PN: An unusual gingivitis among adolescent navajo Indians. periodontics 1963;1:255-259.

- 1 2 3 4 Hedin, CA; Karpe, B; Larsson, A (1994). "Plasma-cell gingivitis in children and adults. A clinical and histological description.". Swedish dental journal. 18 (4): 117–24. PMID 7825113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Janam, P; Nayar, BR; Mohan, R; Suchitra, A (January 2012). "Plasma cell gingivitis associated with cheilitis: A diagnostic dilemma!". Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology. 16 (1): 115–9. doi:10.4103/0972-124X.94618. PMC 3357019

. PMID 22628976.

. PMID 22628976. - 1 2 Greenberg MS, Glick M (2003). Burket's oral medicine diagnosis & treatment (10th ed.). Hamilton, Ont.: BC Decker. p. 60. ISBN 1550091867.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 797. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ Hanami, Y; Motoki, Y; Yamamoto, T (Feb 15, 2011). "Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical tacrolimus: report of two cases.". Dermatology online journal. 17 (2): 6. PMID 21382289.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CA, Bouquot JE (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 141, 142. ISBN 0721690033.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, eds. (2012). Carranza's clinical periodontology (11th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-1-4377-0416-7.