Poland in the Early Middle Ages

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Poland | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||

| Prehistory and protohistory | ||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Early Modern | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Modern | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Contemporary | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

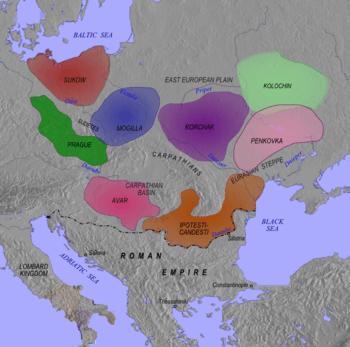

The main event that took place within the lands of Poland in the Early Middle Ages, as well as other parts of central-eastern Europe, was the arrival, and subsequent permanent settlement, of the Slavic peoples.[1][2] The Slavic migrations in the area of contemporary Poland started in the second half of the 5th century CE, some half century after these territories were vacated by Germanic tribes, their previous inhabitants.[1][2] The first waves of the incoming Slavs settled the vicinity of the upper Vistula River and elsewhere in the lands of present southeastern Poland and southern Masovia. Coming from the east, from the upper and middle regions of the Dnieper River,[3] the immigrants would have had come primarily from the western branch of the early Slavs known as Sclaveni,[4] and since their arrival are classified as West Slavs.[a] Their early archeological traces belong to the Prague-Korchak culture, which is similar to the earlier Kiev culture.

From there the new population dispersed north and west over the course of the 6th century. The Slavs lived from cultivation of crops and were generally farmers, but also engaged in hunting and gathering. The migrations took place when the destabilizing invasions of eastern and central Europe by waves of people and armies from the east, such as the Huns, Avars and Magyars, were occurring. This westward movement of Slavic people was facilitated in part by the previous emigration of Germanic peoples toward the safer and more developed areas of western and southern Europe. The immigrating Slavs formed various small tribal organizations beginning in the 8th century, some of which coalesced later into larger, state-like ones.[5][6] Beginning in the 7th century, these tribal units built many fortified structures with earth and wood walls and embankments, called gords. Some of them were developed and inhabited, others had a very large empty area inside the walls.

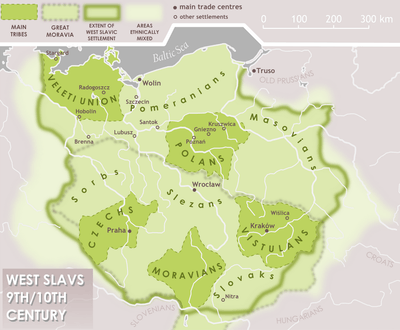

By the 9th century, the Slavs had settled the Baltic coast in Pomerania, which subsequently developed into a commercial and military power.[7] Along the coastline, remnants of Scandinavian settlements and emporia were to be found. The most important of them was probably the trade settlement and seaport of Truso,[8] located in Prussia. Prussia itself was relatively unaffected by Slavic migration and remained inhabited by Baltic Old Prussians. During the same time, the tribe of the Vistulans (Wiślanie), based in Kraków and the surrounding region, controlled a large area in the south, which they developed and fortified with many strongholds.

During the 10th century, the Polans (Polanie, lit. "people of the fields") turned out to be of decisive historic importance. Initially based in the central Polish lowlands around Giecz, Poznań and Gniezno, the Polans went through a period of accelerated building of fortified settlements and territorial expansion beginning in the first half of the 10th century. Under Mieszko I of the Piast dynasty, the expanded Polan territory was converted to Christianity in 966, which is generally regarded the birth of the Polish state. The contemporary names of the realm, "Mieszko's" or "Gniezno state", were dropped soon afterwards in favour of "Poland", a rendering of the Polans' tribal name. The Piast dynasty would continue to rule Poland until the late 14th century.[6][9]

Origin of the Slavic peoples

Slavic beginnings of Poland

The origins of the Slavic peoples, who arrived on Polish lands at the outset of the Middle Ages, archeologically as the Prague culture, go back to the Kiev culture, which formed beginning early in 3rd century CE, and which is genetically derived from the Post-Zarubintsy cultural horizon (Rakhny–Ljutez–Pochep material culture sphere),[10] and itself was one of the later post-Zarubintsy culture groups.[11] Such ethnogenetic relationship is apparent between the large Kiev culture population and the early (6th–7th centuries) Slavic settlements in the Oder and Vistula basins, but lacking between these Slavic settlements and the older local cultures within the same region, that ceased to exist beginning in the 400–450 CE period.[12][13]

Zarubintsy culture

The Zarubintsy culture circle, in existence roughly from 200 BCE to 150 CE, extended along the middle and upper Dnieper and its tributary the Pripyat River, but also left traces of settlements in parts of Polesie and the upper Bug River basin. The main distinguished local groups were the Polesie group, the Middle Dnieper group and the Upper Dnieper group. The Zarubintsy culture developed from the Milograd culture in the northern part of its range and from the local Scythian populations in the more southern part. The Polesie group's origin was also influenced by the Pomeranian and Jastorf cultures. The Zarubintsy culture and its beginnings were moderately affected by La Tène culture and the Black Sea area (trade with the Greek cities provided imported items) centers of civilization in the earlier stages, but not much by Roman influence later on, and accordingly its economic development was lagging behind that of other early Roman period cultures. Cremation of bodies was practiced, with the human remains and burial gifts including metal decorations, small in number and limited in variety, placed in pits.[14]

Kiev culture

Originating from the Post-Zarubintsy cultures and often considered the oldest Slavic culture, the Kiev culture functioned during the later Roman periods (end of 2nd through mid-5th century)[15] north of the vast Chernyakhov culture territories, within the basins of the upper and middle Dnieper, Desna and Seym rivers. The archeological cultural features of the Kiev sites show this culture to be identical or highly compatible (representing the same cultural model) with that of the 6th-century Slavic societies, including the settlements on the lands of today's Poland.[12] The Kiev culture is known mostly from settlement sites; the burial sites, involving pit graves, are few and poorly equipped. Not many metal objects have been found, despite the known native production of iron and processing of other metals, including enamel coating technology. Clay vessels were made without the potter's wheel. The Kiev culture represented an intermediate level of development, between that of the cultures of the Central European Barbaricum, and the forest zone societies of the eastern part of the continent. The Kiev culture consisted of four local formations: The Middle Dnieper group, the Desna group, the Upper Dnieper group and the Dnieper-Don group. The general model of the Kiev culture is like that of the early Slavic cultures that were to follow and must have originated mainly from the Kiev groups, but evolved probably over a larger territory, stretching west to the base of the Eastern Carpathian Mountains, and from a broader Post-Zarubintsy foundation. The Kiev culture and related groups expanded considerably after 375 CE, when the Ostrogothic state,[16] and more broadly speaking the Chernyakhov culture, were destroyed by the Huns.[17][18][c] This process was facilitated further and gained pace, involving at that time the Kiev's descendant cultures, when the Hun confederation itself broke down in the mid-5th century.[19][20]

Written sources

The eastern cradle of the Slavs is also directly confirmed by a written source. The anonymous author known as the Cosmographer of Ravenna (c. 700) names Scythia, a geographic region encompassing vast areas of eastern Europe,[12] as the place "where the generations of the Sclaveni had their beginnings".[20] Scythia, "stretching far and spreading wide" in the eastern and southern directions, had at the west end, as seen at the time of Jordanes' writing (first half to mid-6th century) or earlier, "the Germans and the river Vistula".[21] Jordanes places the Slavs in Scythia as well.[21]

Alternative point of view

According to an alternative theory, popular in the earlier 20th century and still represented today, the medieval cultures in the area of modern Poland are not a result of massive immigration, but emerged from a cultural transition of earlier indigenous populations, who then would need to be regarded as early Slavs. This view has mostly been discarded, primarily due to a period of archaeological discontinuity, during which settlements were absent or rare, and because of cultural incompatibility of the late ancient and early medieval sites.[5][6][b]

A 2011 article on the early Western Slavs states that the transitional period (of relative depopulation) is difficult to evaluate archeologically. Some believe that the Late Antique "Germanic" populations (in Poland late Przeworsk culture and others) abandoned East Central Europe and were replaced by the Slavs coming from the east, others see the "Germanic" groups as staying and becoming, or already being, Slavs. Current archeology, says the author, "is unable to give a satisfying answer and probably both aspects played a role". In terms of their origin, territorial and linguistic, "Germanic" groups should not be played off against "Slavs", as our current understanding of the terms may have limited relevance to the complex realities of the Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages. Local languages in the region cannot be identified by archeological studies, and genetic evaluation of cremation burial remains has not been possible.[22]

Slavic differentiation and expansion; Prague culture

Kolochin culture, Penkovka culture and Prague–Korchak culture

The final process of the differentiation of the cultures recognized as early Slavic, the Kolochin culture (over the Kiev culture's territory), the Penkovka culture and the Prague-Korchak culture took place during the end of the 4th and in the 5th century CE. Beyond the Post-Zarubintsy horizon the expanding early Slavs took over much of the territories of the Chernyakhov culture and the Dacian Carpathian Tumuli culture. As not all of the previous inhabitants (from those cultures) had left the area and some groups were assimilated, they probably contributed some elements to the Slavic cultures.[15]

The Prague culture developed over the western part of the Slavic expansion, within the basins of the middle Dnieper, Pripyat, upper Dniester, up to the Carpathian Mountains and in southeastern Poland, that is the upper and middle Vistula basin. This culture was responsible for most of the growth in 6th and 7th centuries, by which time it also encompassed the middle Danube and middle Elbe basins.[12] The Prague culture very likely corresponds to Jordanes' Sclaveni, whose area he described as extending west to the Vistula sources. The Penkovka culture people inhabited the southeastern part, from Seversky Donets to the lower Danube (including the region where the Antes would be), and the Kolochin culture was located north of the more eastern area of the Penkovka culture (the upper Dnieper and Desna basins). The Korchak type designates the eastern part of the Prague-Korchak culture, which because of its western expansion is somewhat less directly dependent on the mother Kiev culture than its two sister cultures. The early 6th-century Slavic settlements covered an area three times the size of the Kiev culture region some hundred years earlier.[12][23]

Early settlements, economy and burials in Poland

In Poland the earliest archeological sites considered Slavic include a limited number of 6th-century settlements and a few isolated burial sites. The material obtained there consists mostly of simple, manually formed ceramics, typical of the entire early Slavic area. It is because of the different varieties of these basic clay pots and infrequent decorations that the three cultures are distinguished.[24] The largest of the earliest Slavic (Prague culture) settlement sites in Poland that have been subjected to systematic research is located in Bachórz, Rzeszów County and dated the second half of 5th through 7th centuries. It consisted of 12 nearly square, partially dug out houses, each covering the area of 6.2 to 19.8 (14.0 on the average) square meters. A stone furnace was usually placed in a corner, which is typical for Slavic homesteads of that period, but clay ovens and centrally located hearths are also found.[12] 45 younger, different type dwellings (7th/8th to 9th/10th centuries) have also been discovered in the vicinity.[25][26]

Characteristic of all early Slavic cultures are poorly developed handicraft and limited resources of their communities. There were no major iron production centers, but metal founding techniques were known; among metal objects occasionally found are iron knives and hooks, as well as bronze decorative items (7th-century finds in Haćki, Bielsk Podlaski County, a site of one of the earliest fortified settlements). The inventories of the typical, rather small, open settlements include normally also various clay (including weights used for weaving), stone and horn utensils. The developments arranged as clusters of cabins along river or stream valleys, but above their flood levels, were usually irregular, and typically faced south. The wooden frame or pillar supported square houses covered with a straw roof had each side 2.5 to 4.5 meters long. Fertile lowlands were sought, but also forested areas with diversified plant and animal environment to provide additional sustenance. The settlements were self-sufficient—the early Slavs functioned without significant long-distance trade. The potter's wheel was being used from the turn of 7th century on. Some villages larger than a few homes have been investigated in the Kraków-Nowa Huta region (6th to 9th century, for example cottages from about 625 CE), where, on the left bank of the Vistula, in the direction of Igołomia a complex of 11 settlements has been located. The original furnishings of Slavic huts are difficult to determine, because equipment was often made of perishable materials such as wood, leather or fabrics. Free standing clay dome stoves for bread baking were found on some locations. Another large 6th– to 9th-century settlement complex existed in the vicinity of Głogów in Silesia.[27][28][29]

Like others for many centuries in this part of the world, the Slavic people cremated their dead. The burials were usually single, the graves grouped in small cemeteries, with the ashes placed in simple urns more often than in ground indentations. The number of burial sites found is small in relation to the known settlement density. The food production economy was based on millet and wheat cultivation, cattle breeding (swine, sheep and goats to a lesser extent), hunting, fishing and gathering.[1]

Geographic expansion in Poland and central Europe

As the Slavs were arriving from the east beginning in the second half of 5th century, the earliest settlers reached southeastern Poland, that is the San River basin, then the upper Vistula regions including the Kraków area and Nowy Sącz Valley. Single early sites are also known around Sandomierz, Lublin, in Masovia and Upper Silesia. Somewhat younger settlement concentrations were discovered in Lower Silesia. In the 6th century the above areas were settled. At the end of this century, or in early 7th century the Slavic newcomers reached Western Pomerania. According to Theophylact Simocatta, the Slavs captured in 592 at Constantinople named the Baltic Sea coastal area as the place they came from.[30][31]

As of that time and in the following decades this region, plus some of the Greater Poland, Lower Silesia and some areas west of the middle and lower Oder River make up the Sukow-Dziedzice group. Its origin is the subject of debate among archeologists. First settlements appear in the early 6th century and cannot be directly derived from any other Slavic archeological culture. They reveal certain similarities to the findings of Dobrodzień group of the Przeworsk culture. According to some scholars like Siedow, Kurnatowska and Brzostowicz, it might be a direct continuation of the Przeworsk tradition. According to allochthonists, it represents a variant of the Prague culture and is considered its younger stage. Sukow-Dziedzice group shows significant idiosyncrasies, as no graves or (typical for the rest of the Slavic world) rectangular dwellings set partially below the ground level were found within its span.[1][12]

This particular pattern of expansion into the lands of Poland and then Germany (another, more southern 6th-century route took the Prague culture Slavs through Slovakia, Moravia and Bohemia)[32] was a part of the great Slavic migration, which took many of them during this 5th– to 7th-century period from the lands of their origin to the various countries of central and southeastern Europe.[33][34] In particular the Slavs reached the eastern Alps, populated the Elbe basin, and the Danube basin, from where they moved south to occupy the Balkans as far as Peloponnese.[12]

Slavic related Ancient and early Medieval written accounts

Besides the Baltic Veneti (see Poland in Antiquity article), ancient and medieval authors speak of the East European, or Slavic Venethi. It can be inferred from Tacitus' description in Germania that his "Venethi" lived possibly around the middle Dnieper basin,[35] which in his times would correspond to the Proto-Slavic Zarubintsy cultural sphere. Jordanes, to whom the Venethi meant his contemporary Slavs, wrote of past fighting between the Ostrogoths and the Venethi, which took place during the third quarter of 4th century in today's Ukraine.[36] At that time the Venethi would therefore mean the Kiev culture people. The Venethi says Jordanes, who "now rage in war far and wide, in punishment for our sins",[21] were at that time made obedient to the Gothic king Hermanaric's command. Jordanes' 6th-century description of the "populous race of the Venethi"[21] range includes the regions near the left (northern) ridge of the Carpathian Mountains and stretching from there "almost endlessly" east, while in the western direction reaching the sources of the Vistula. More specifically he designates the area between the Vistula and the lower Danube as the country of the Sclaveni. "They have swamps and forests for their cities" (hi paludes silvasque pro civitatibus habent),[21][37] he adds sarcastically. The "bravest of these peoples",[21] the Antes, settled the lands between the Dniester and the Dnieper rivers. The Venethi were the third Slavic branch of an unspecified location (the more distant from Jordanes' vantage and more ancestral in relation to the other two, the Kolochin culture is the likely possibility), as well as the overall designation for the totality of the Slavic peoples, who "though off-shoots from one stock, have now three names".[21] Procopius in De Bello Gothico located the "countless Antes tribes" even further east, beyond the Dnieper.[38] Together with the Sclaveni they spoke the same language, of an "unheard of barbarity".[38] According to him the Heruli nation traveled in 512 across all of the Sclaveni peoples territories, and then west of there through a large expanse of unpopulated lands, as the Slavs were about to settle the western and northern parts of Poland in the decades to follow.[12] All of the above is in good accordance with the findings of today's archeology.[39][40]

Byzantine writers held the Slavs in low regard for the simple life they lived and also for their supposedly limited combat abilities, but in fact they were already in the early 6th century a threat to the Danubian boundaries of the Empire, where they waged plundering expeditions. Procopius, the anonymous author of Strategicon known as Pseudo-Maurice and Theophylact Simocatta wrote at some length on how to deal with the Slavs militarily, which suggests that they had become a formidable adversary. John of Ephesus actually goes as far as saying (the last quarter of 6th century), that the Slavs had learned to conduct war better than the Byzantine army. The Balkan Peninsula was indeed soon overrun by the Slavic invaders, during the first half of 7th century, under Emperor Heraclius.[15][41]

The above-mentioned authors provide various details on the character, lifestyle and living conditions, social structure and economic activities of the early Slavic people, some of which are confirmed by the archeological discoveries as far as in Poland, as the Slavic communities were quite similar all over their range.[41] Their uniform Old Slavic language remained in use until, depending on the region, the 9th to 12th centuries. For example, the Greek missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius from Thessaloniki, where "everybody fluently spoke Slavic", when sent in 863 by the Byzantine ruler to distant Moravia, were expected to be able to communicate there without any difficulty.[42]

Avar invasions in Europe and their presence in Poland

In the 6th century, the Turkic speaking nomadic Avars moved into the middle Danube area. Twice (562 and 566–567) the Avars had undertaken military expeditions against the Franks and their routes went through the Polish lands. The Avar envoys bribed Slavic chiefs from the lands they did not control, including Pomerania, to secure their participation in Avar raids, but other than that the exact nature of their relations with the Slavs in Poland is not known. The Avars had some presence or contacts there also in the 7th and 8th centuries, when they left artifacts in the Kraków-Nowa Huta region and elsewhere, including a bronze belt decoration found in the Krakus Mound. This last item, from the turn of 8th century, is used to date the mound itself.[43][44][45][d]

Tribal differentiation

8th-century settlements

With the major population shifts completed, the 8th century brought a measure of stability to the Slavic people settled in Poland. About one million people actively developed and utilized no more than 20–25% of the land, the rest being forest. Normal settlements, with the exception of a few fortified and cult places, were limited to lowland areas, below 350 meters above the sea level. Most villages built without artificial defensive structures were located within valley areas of natural bodies of water. The Slavs were very familiar with the water environment and used it as natural defense.[46]

The living and economic activity structures were either distributed randomly, or arranged in rows or around a central empty lot. The larger settlements could have had over a dozen homesteads and be occupied by 50 to 80 residents, but more typically there were just several homes with no more than 30 inhabitants. From the 7th century on the previously common semi-subterranean dwellings were being replaced by buildings located over most of their areas or wholly above the surface (pits were dug for storage and other uses), but still consisted of just one room. As the Germanic people before, the Slavs were leaving no man's land regions between developed areas, and especially along the limits of their tribal territories, for separation from strangers and to avoid conflicts.[46]

Gord construction

The Polish tribes did however leave remnants of more imposing structures—fortified settlements and other reinforced enclosures of the gord (Polish "gród") type. Those were being established on naturally suitable, defense enhancing sites beginning in late 6th or 7th century (Szeligi near Płock and Haćki are the early examples),[47] with a large scale building effort taking place in the 8th century. The gords were differently designed and of various sizes, from small to impressively massive. Ditches, walls, palisades and embankments were used to strengthen the perimeter, which involved an often complicated earthwork, wood and stone construction. Gords of the tribal period were irregularly distributed across the country (fewer larger ones in Lesser Poland, more smaller ones in central and northern Poland),[48] could cover an area from 0.1 to 25 hectares, have a simple or multi-segment architecture, and be protected by fortifications of different types. Some were permanently occupied by a substantial number of people or by a chief and his cohort of armed men, while others were utilized as refuges to protect the local population in case of external danger. The gords eventually (beginning in the 9th century) became the nuclei of future urban developments, attracting, especially in strategic locations, tradesmen of all kinds. Gords erected in the 8th century have been investigated for instance in Międzyświeć (Cieszyn County, Gołęszyce tribe) and Naszacowice (Nowy Sącz County). The last one was destroyed and rebuilt four times, with the final reconstruction after 989.[46]

A monumental (over 3 hectares) and technically complex border protection area gord was built around 770–780 in Trzcinica near Jasło, on the site of an old Bronze Age era stronghold, probably the seat of a local ruler and his garrison. Thousands of relics were found there including a 600 pieces silver treasure. The gord was set afire several times and ultimately destroyed during the first half of the 11th century.[49][e]

This larger scale gord building activity, from the mid-8th century on, was a manifestation of the emergence of tribal organisms, a new civilizational quality, representing rather efficient proto-political organizations and social structures on a new level. They were based on these fortifications, defensive objects, of which the mid-8th century and later Vistulan gords in Lesser Poland are a good example. The threat coming from the Avar state in Pannonia could have had provided the original motivation for the organizing and the construction projects.[50]

Society organized into larger tribal units

The Slavs in Poland, from the 8th century on, increasingly organized in larger structures, known as great tribes, either through voluntary or forced association, were primarily agricultural people. Fields were cultivated, as well as, within settlements, nearby gardens. Plowing was done using oxen and wooden, iron reinforced plows. Forest burning was used to increase the arable area, but also provided fertilizer, as the ashes lasted in that capacity for several seasons. Rotation of crops was practiced as well as the winter/spring crop system. After several seasons of exploitation the land was being left idle to regain fertility. Wheat, millet and rye were most important; other cultivated plant species included oat, barley, pea, broad bean, lentil, flax, hemp, as well as apple, pear, plum, peach and cherry trees in fruit orchards. Beginning in the 8th century, swine gradually became economically more important than cattle; sheep, goats, horses, dogs, cats, chickens, geese and ducks were also kept. The Slavic agricultural practices are known from archeological research, which shows progressive over time increases in arable area and resulting deforestation,[51] and from written reports provided by Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, a 10th-century Jewish traveler. Ibrahim described also other features of Slavic life, for example the use of steam baths. The existence of bath structures has been confirmed by archeology.[52] An anonymous Arab writer from the turn of the 10th century mentions that the Slavic people made an alcoholic beverage out of honey and their celebrations were accompanied by music played on the lute, tambourines and wind instruments.[46]

Gathering, hunting and fishing were still essential as sources of food and materials, such as hide or fur. The forest was also exploited as a source of building materials such as wood, wild forest bees were kept there, and as a place of refuge.[53] The population was, until the 9th century, separated from the main centers of civilization, self-sufficient with primitive, local community and household based manufacturing. Specialized craftsmen (of rather mediocre qualifications) existed only in the fields of iron extraction from ore and processing, and pottery; the few luxury type items used were imports. From the 7th century on, modestly decorated ceramics was made with the potter's wheel. 7th– to 9th-century collections of objects have been found in Bonikowo and Bruszczewo, Kościan County (iron spurs, knives, clay containers with some ornamentation) and in Kraków-Nowa Huta region (weapons and utensils in Pleszów and Mogiła, where the most substantial of iron treasures was located), among other places. Slavic warriors were traditionally armed with spears, bows and wooden shields; occasionally seen later axes and still later swords are of the types popular throughout 7th– to 9th-century Europe. Independent of distant powers the Slavic tribes in Poland lived a relatively undisturbed life, but at the cost of some civilizational backwardness.[46]

A qualitative change took place in the 9th century, when the Polish lands were crossed again by long-distance trade routes, with Pomerania becoming a part of the Baltic trade zone, while Lesser Poland participated in exchange centered in the Danubian countries. Oriental silver jewelry and Arab coins, often cut into pieces, "grzywna" iron coin equivalents (of the type used in Great Moravia) in the Upper Vistula basin and even linen cloths served as currency.[46]

The basic social unit was the nuclear family, consisting of parents and their children, which had to fit in a dwelling area of several to 25 square meters. The big family, a patriarchal, multi-generational group of related families, a kin or clan, was of declining importance during the discussed period. A larger group was needed in the past (5th–7th centuries) for forest clearing and burning undertakings, when farming communities had to shift from location to location; in the 8th-century mature—settled phase of agriculture, a family was sufficient to take care of their arable land.[54] A concept of agricultural land ownership was gradually developing, being at this point a matter of family, not individual prerogative. Several or more clan territories were grouped into a neighborhood association, or "opole", which established a rudimentary self-government. Such community was the owner of forested land, pastures, bodies of water and within it the first organizing around common projects and related development of political power took place. A big and resourceful opole could become, by extending its possessions, a proto-state entity vaguely referred to as the tribe.[55] The tribe was the top level of this structure, containing several opoles and controlling a region of several hundred up to about 1500 square kilometers, where internal relationships were arbitrated and external defense organized.[46]

A general assembly of all tribesmen present took care of the most pressing of issues (Thietmar of Merseburg wrote in the early 11th century of the Veleti, Polabian Slavs, that their assembly kept deliberating till everybody agreed), but this "war democracy" was gradually being replaced by a government system in which the tribal elders and rulers had the upper hand. This development facilitated the coalescing of tribes into great tribes, some of which under favorable conditions would later become tribal states. The communal and tribal democracy, with self-imposed contributions by the community members, survived in small entities and local territorial subunits the longest; on a larger scale it was being replaced by the rule of able leaders and then dominant families, ultimately leading inevitably to hereditary transition of supreme power, mandatory taxation, service etc.[56] When social and economic evolution reached this level, the concentration of power was facilitated and made possible to sustain by parallel development of a professional military force (called at this stage "drużyna") at the ruler's or chief's disposal.[46][57]

Burials and religion

The burial customs, at least in southern Poland, included raising kurgans. The urn with the ashes was placed on the mound or on a post thrust into the ground. In that position few such urns survived, which may be why Slavic burial sites in Poland are rare. All dead, regardless of social status, were cremated and afforded a burial, according to Arab testimonies (one from the end of 9th century and another one from about 930). A Slavic funeral feast practice was also mentioned earlier by Theophylact Simocatta.[58]

According to Procopius the Slavs believed in one god, creator of lightning and master of the entire universe, to whom all sacrificial animals (sometimes people) were offered. The highest god was called Svarog throughout the Slavic area, as other gods were worshiped too in different regions at different times, often with local names.[59] Natural objects such as rivers, groves or mountains were also celebrated, as well as nymphs, demons, ancestral and other spirits, who were all venerated and bought off with offering rituals, which also involved augury. Such beliefs and practices were later continued, developed further and individualized by the many Slavic tribes.[60][61]

The Slavs erected sanctuaries, created statues and other sculptures including the four-faced Svetovid, whose carvings symbolize various aspects of the Slavic cosmology model. One 9th-century specimen from the Zbruch River in today's Ukraine, found in 1848, is on display at the Archeological Museum in Kraków. Many of the sacred locations and objects were identified outside Poland, in northeastern Germany or Ukraine. In Poland religious activity sites have been investigated in northwestern Pomerania, including Szczecin, where a three-headed deity once stood and the Wolin island, where 9th– to 11th-century cult figurines were found.[62] Archeologically confirmed cult places and figures have also been researched at several other locations.[63]

Early Slavic states and other 9th-century developments

Samo's realm

The first Slavic state-like entity, the Samo's Realm of King Samo, originally a Frankish trader, was close to Poland (in Bohemia and Moravia, parts of Pannonia and more southern regions between the Oder and Elbe rivers) and existed during the 623–658 period.[64] Samo became a Slavic leader by successfully helping the Slavs defend themselves against the Avar assailants. What Samo led was probably a loose alliance of tribes and it fell apart after his death. Slavic Carantania, centered on Krnski Grad (now Karnburg in Austria), was more of a real state, developed possibly from one part of the disintegrating Samo's kingdom, but lasted under a native dynasty throughout the 8th century and became Christianized.[65]

Great Moravia

Larger scale state-generating processes and in more remote (in relation to Byzantium) Slavic areas took place in the 9th century. Great Moravia became established in the early 9th century south of today's Poland, but eventually encroached on and also included the Silesia and very likely southern Lesser Poland regions. The glory of the Great Moravian empire became fully apparent in light of archeological discoveries, of which lavishly equipped burials are especially spectacular.[65] Such finds however do not extend to the peripheral areas of Great Moravia, the lands that now constitute southern Poland. The great territorial expansion of Great Moravia took place during the reign of Svatopluk I, at the end of 9th century. Beyond the original Moravia and western Slovakia the Great Moravian state incorporated then also, to various degrees, Bohemia, Pannonia and the above-mentioned regions of Poland. In 906 Great Moravia, weakened by an internal crisis and Magyar invasions, ceased to exist.[65]

In 831 Mojmir I was baptized and his Moravian state became a part of the Bavarian Passau diocese. Aiming to achieve ecclesiastical as well as political independence from East Frankish influence, his successor Rastislav asked the Byzantine emperor Michael III for missionaries. As a result, Cyril and Methodius arrived in Moravia in 863 and commenced missionary activities among the Slavic people there. To further their goals the brothers developed a written Slavic liturgical language—the Old Church Slavonic, using the Glagolitic alphabet created by them. Into this language they translated the Bible and other church texts, thus establishing a foundation for the later Slavic Eastern Orthodox churches.[65]

Czech state

The fall of Great Moravia made room for the expansion of the Czech or Bohemian state, which likewise incorporated some of the Polish lands. The founder of the Přemyslid dynasty, Prince Bořivoj was baptized by Methodius in the Slavic rite during the later part of the 9th century and settled in Prague. His son and successor Spytihněv was baptized in Regensburg in the Latin rite, which marks the early stage of East Frankish/German influence, destined to be decisive in Bohemian affairs.[66] Borivoj's grandson Prince Wenceslaus, the future Czech martyr and patron saint, was killed, probably in 935, by his brother Boleslaus. Boleslaus I solidified the power of the Prague princes and most likely dominated the Lesser Poland's Vistulans and Lendians tribes and at least parts of Silesia.[65]

9th-century Polish lands

In the 9th century the Polish lands were still on the peripheries in relation to the major powers and events of medieval Europe, but a measure of civilizational progress did take place, as evidenced by the number of gords built, kurgans raised and movable equipment used. The tribal elites must have been influenced by the relative closeness of the Carolingian Empire; objects crafted there have occasionally been found.[48][67] Poland was populated by many tribes of various sizes. The names of some of them, mostly from western part of the country, are known from written sources, especially the Latin-language document written in the mid-9th century by the anonymous Bavarian Geographer. During this period typically smaller tribal structures were disintegrating, larger ones were being established in their place.[68]

Characteristic of the turn of the 10th century in most Polish tribal settlement areas was a particular intensification of gord building activity. The gords were the centers of social and political life. Tribal leaders and elders had their headquarters in their protected environment and some of the tribal general assemblies took place inside them. Religious cult locations were commonly located in the vicinity, while the gords themselves were frequently visited by traders and artisans.[65]

Vistulan state

A major development of this period concerns the somewhat enigmatic Wiślanie, or Vistulans (Bavarian Geographer's Vuislane) tribe. The Vistulans of western Lesser Poland, mentioned in several contemporary written sources, already a large tribal union in the first half of the 9th century,[69] were evolving in the second half of that century toward a super-tribal state, until their efforts were terminated by the more powerful neighbors from the south. Kraków, the main town of the Vistulans, with its Wawel gord, was located along a major "international" trade route. The main Vistulan-related archeological find (in addition to the 8th-century Krakus, Wanda and other large burial mounds and the remnants of several gords)[70] is the late 9th-century treasure of iron-ax shaped grzywnas, well known as currency units in Great Moravia. They were discovered in 1979 in a wooden chest, below the basement of a medieval house on Kanonicza Street, near the Vistula and the Wawel Hill. The total weight of the iron material is 3630 kilograms and the individual bars of various sizes (4212 of them) were bound in bundles, which suggests that the package was being readied for transportation.[71]

According to Constantine VII, in the 7th century Croats were dwelling beyond Bavaria, where White Croats lived in the 10th century. That was probably around the Upper Vistula region and in northern Bohemia. In the 7th century a Croat family of five brothers and two sisters left the area with their folk, and came to Dalmatia, with permission of Emperor Heraclius, to help defend the imperial borders.[72]

Vistulan gords, built from the mid-8th century on, had typically very large area, often over 10 hectares. About 30 big ones are known. The 9th-century gords in Lesser Poland and in Silesia had likely been built as a defense against Great Moravian military expansion.[73] The largest one, in Stradów, Kazimierza Wielka County, had an area of 25 hectares and walls or embankments up 18 meters high, but parts of this giant structure were probably built later. The gords were often located along the northern slope of the western Carpathian Mountains, on hills or hillsides. The buildings inside the walls were sparsely located or altogether absent, so for the most part the gords' role was other than that of settlements or administrative centers.[74]

A large (2.5 hectares) gord was built at the turn of the 9th century in Zawada Lanckorońska, Tarnów County, and rebuilt after 868. A treasure found there contains various Great Moravian type decorations dated from the late 9th century through mid-10th century. The treasure was hidden and the gord destroyed by fire during the second half of that century.[75]

The large mounds, up to 50 meters in diameter, are found not only in Kraków, but also in Przemyśl and Sandomierz among other places (about 20 total).[74] They were probably funeral locations of rulers or chiefs, with the actual burial site, on the top of the mound, long lost.[76] Besides the mounds-kurgans, the degree of the Wawel gord development (built in the 8th century) and the grzywna treasure point to Kraków as the main center of Vistulan power (in the past Wiślica was also suspected of that role).[69]

The most important Vistulans related written reference comes from The Life of Saint Methodius, also known as The Pannonian Legend, written by Methodius' disciples most likely right after his death (885).[77] The fragment speaks of a very powerful pagan prince, residing in the Vistulan country, who reviled the Christians and caused them great harm. He was warned by St. Methodius' emissaries speaking on the missionary's behalf (St. Methodius himself may have been acting as Svatopluk's agent here), advised to reform and voluntarily accept baptism in his own homeland. Otherwise, it was predicted, he would be forced to do so in a foreign land, and, according to the Pannonian Legend story, that is what eventually happened. This passage is widely interpreted as the indication that the Vistulans were invaded and overrun by the army of Great Moravia and their pagan prince captured. It would have to happen during Methodius' second stay in Moravia, between 873 and 885, and during Svatopluk's reign.[69]

A further elaboration on this story is possibly found in the chronicle of Wincenty Kadłubek, written some three centuries later. The chronicler, inadvertently or intentionally mixing different historic eras, talks of a past Polish war with the army of Alexander the Great. The countless enemy soldiers thrust their way into Poland, and the King himself, having previously subjugated the Pannonians, entered through Moravia like through the back door. He victoriously unfolded the wings of his forces and conquered the Kraków area lands and Silesia, leveling in process Kraków's ancient city walls. It appears that at some point during the intervening period, or by the chronicler himself, the glitter of the Svatopluk's army became confused with that of the emperor-warrior of another place and time. A dozen or more southern Lesser Poland gords attacked and destroyed at the end of 9th century lends some archeological credence to this version of events.[74]

East of the Vistulans, eastern Lesser Poland was the territory of the Lendians (Lędzianie, Bavarian Geographer's Lendizi) tribe. In the mid-10th century Constantine VII wrote their name as Lendzaneoi.[68] The Lendians had to be a very substantial tribe, since the names for Poland in the Lithuanian and Hungarian languages and for the Poles in medieval Ruthenian all begin with the letter "L", being derived from their tribe's name. The Poles historically have also referred to themselves as "Lechici". After the fall of Great Moravia the Magyars controlled at least partially the territory of the Lendians.[78] The Lendians were conquered by Kievan Rus' during 930–940; at the end of the 10th century the Lendian lands became divided, with the western part taken by Poland, the eastern portion retained by Kievan Rus'.[79]

The Vistulans were probably also subjected to Magyar raids, as an additional layer of embankments was often added to the gord fortifications in the early part of the 10th century. In the early or mid-10th century the Vistulan entity, like Silesia, was incorporated by Boleslaus I of Bohemia into the Czech state.[68] This association turned out to be beneficial in terms of economic development, because Kraków was an important station on the Prague—Kiev trade route. The first known Christian church structures were erected on the Wawel Hill. Later in the 10th century, under uncertain circumstances but in a peaceful way (the gord network suffered no damage on this occasion), the Vistulans became a part of the Piast Polish state.

Baltic coast

In terms of economic and general civilizational achievement the most advanced region in the 9th century was Pomerania, characterized also by most extensive contacts with the external world, and accordingly, cultural richness and diversity. Pomerania was a favorite destination for traders and other entrepreneurs from distant lands, some of whom were establishing local manufacturing and trade centers; those were usually accompanied by nearby gords inhabited by the local elite. Some of such industrial area / gord complexes gave rise to early towns—urban centers, such as Wolin, Pyrzyce or Szczecin. The Bavarian Geographer mentioned two tribes, the Velunzani (Uelunzani) and Pyritzans (Prissani) in the area, each with 70 towns. Despite the high civilizational advancement, no social structures indicative of statehood developed in Farther Pomeranian societies, except for the Wolin city-state.[80]

The Wolin settlement was established on the island of the same name in the late 8th century. Located at the mouth of the Oder River, Wolin from the beginning was involved with long distance Baltic Sea trade. The settlement, thought to be identical with both Vineta and Jomsborg, was pagan, multiethnic, and readily kept accepting newcomers, especially craftsmen and other professionals, from all over the world. Being located on a major intercontinental sea route, it soon became a big European industrial and trade power. Writing in the 11th century Adam of Bremen saw Wolin as one of the largest European cities, inhabited by honest, good-natured and hospitable Slavic people, together with other nationalities, from the Greeks to barbarians, including the Saxons, as long as they did not demonstrate their Christianity too openly.[7]

Wolin was the major stronghold of the Volinian tribal territory, comprising the island and a broad stretch of the adjacent mainland, with its frontier guarded by a string of gords. The city's peak of prosperity occurred around and after year 900, when a new seaport was built (the municipal complex had now four of them) and the metropolitan area was secured by walls and embankments. The archeological findings there include a great variety of imported (even from the Far East) and locally manufactured products and raw materials; amber and precious metals figure prominently, as jewelry was one of the mainstay economic activities of the Wolinian elite.[7]

Truso in Prussia was another Baltic seaport and trade emporium known from the reworking of the Orosius' universal history by Alfred the Great. King Alfred included a description of the voyage undertaken around 890 by Wulfstan from the Danish port of Hedeby to Truso located near the mouth of the Vistula. Wulfstan gave a rather detailed description of the location of Truso, within the land of the Aesti, yet right close to the Slavic areas across (west of) the Vistula. Truso's actual site was discovered in 1982 at Janów Pomorski, near Elbląg.[8]

Established as a seaport by the Vikings and Danish traders at the end of the 8th century in the Prussian border area previously already explored by the Scandinavians, Truso lasted as a major city and commercial center until the early 11th century, when it was destroyed and by which time it was replaced in that capacity by Gdańsk. The settlement covered an area of 20 hectares and consisted of a two dock seaport, the craft-trade portion, and the peripheral residential development, all protected by a wood and earth bulwark separating it from the mainland. The port-trade and craftsmen zones were themselves separated by a fire control ditch with water flowing through it. There were several rows of houses including long Viking hall structures, waterside warehouses, market areas and wooden beam covered streets. Numerous relics were found, including weights used also as currency units, coins from English to Arab and workshops processing metal, jewelry or large quantities of amber. Remnants of long Viking boats were also found, the whole complex being a testimony to Viking preoccupation with commerce, the mainstay of their activities around the Baltic Sea region. The multi-ethnic Truso had extensive trade contacts not only with distant lands and Scandinavia, but also the Slavic areas located to the south and west of it, from where ceramics and other products were transported along the Vistula in river crafts. Ironically, Truso's sudden destruction by fire and subsequent disappearance was apparently a result of a Viking raid.[81][82][f]

This connection to the Baltic trade zone led to an establishment of inner-Slavic long-distance trade routes. Lesser Poland participated in exchange centered in the Danubian countries. Oriental silver jewelry and Arab coins, often cut into pieces, "grzywna" iron coin equivalents (of the type used in Great Moravia) in the Upper Vistula basin and even linen cloths served as currency.[46]

Magyar intrusion

The Magyars were at first still another wave of nomadic invaders. Of the Uralic languages family, coming from northwestern Siberia, they migrated south and west, occupying from the end of 9th century the Pannonian Basin. From there, until the second half of the 10th century, when they were forced to settle, they raided and pillaged vast areas of Europe, including Poland. A saber and ornamental elements were found in a Hungarian warrior's grave (from the first half of the 10th century) in the Przemyśl area.[45]

Geographically the Magyar invasions interfered with the previously highly influential contacts between Central Europe and Byzantine Christianity centers. It may have been the decisive factor that steered Poland toward the Western (Latin) branch of Christianity by the time of its adoption in 966.[83]

10th-century developments in Greater Poland; Mieszko's state

Tribal Greater Poland

This period brought a notable development in settlement stability on Polish lands. Short-lived prehistoric settlements gradually gave way to villages on fixed sites. The number of villages grew with time, but their sites rarely shifted. The population distribution patterns established from that century on are evident on today's landscape.[84]

Sources from the 9th and 10th centuries make no mention of the Polans (Polanie) tribe. The closest thing would be the huge (400 gords) Glopeani tribe of the Bavarian Geographer, whose name seems to be derived from that of Lake Gopło, but archeological investigations cannot confirm any such scale of settlement activity in Lake Gopło area. What the research does indicate is the presence of several distinct tribes in 9th-century Greater Poland, one around the upper and middle Obra River basin, one in the lower Obra basin, and another one west of the Warta River. There was the Gniezno area tribe, whose settlements were concentrated around the regional cult center—the Lech Hill of today's Gniezno. Throughout the 9th century the Greater Poland tribes did not constitute a uniform entity or whole in the cultural, or settlement pattern sense. The centrally located Gniezno Land was at that time rather isolated from external influences, such as from the highly developed Moravian-Czech or Baltic Sea centers. Such separation (also from the more expansive powers) was probably a positive factor, facilitating at this stage the efforts of a lineage of leaders from an elder clan of a tribe there, known as the Piast House, which resulted in the early part of the 10th century in the establishment of an embryonic state.[85]

Mieszko's state and its origins

What was later to be called Gniezno state, also known as Mieszko's state, was expanded at the expense of the subdued tribes in Mieszko's grandfather and father times, and in particular by Mieszko himself. Writing around 965 or 966 Ibrahim ibn Yaqub described the country of Mieszko, "the king of the North",[g] as the most wide-ranging of the Slavic lands.[86] Mieszko, the ruler of the Slavs, was also mentioned as such at that time by Widukind of Corvey in his Res gestae saxonicae. In its mature form this state included the West Slavic lands between the Oder and Bug rivers and between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains, including the economically crucial mouth areas of the Vistula and Oder rivers, as well as Lesser Poland and Silesia.[86][87]

The name of Poles (Polanians, Polyans, Polans) appears in writing for the first time around year 1000, like the country's name Poland (Latinized as Polonia). "Polanie" was possibly the name given by later historians to the inhabitants of Greater Poland (a presumed tribe not mentioned in earlier sources). 10th-century inhabitants of Greater Poland would originate from unknown (by name) tribes, which were instrumental in bringing about the establishment of the Polish state; one such tribe had to constitute the immediate power base of Mieszko's predecessors, if not Mieszko himself.[86]

Gallus Anonymus' account vs. archeology

In the early 12th century chronicler Gallus Anonymus wrote down or invented a dynastic legend of the House of Piasts. The story gives, amid miraculous details, the names of the supposed ancestors of the royal family, beginning with a man named Chościsko, the father of the central figure Piast, who was a humble farmer living in Gniezno, married to Rzepka. The male heads of the Piast clan following after him were, according to Gallus, Siemowit, Lestek, Siemomysł and Mieszko I, the first "Piast" known with historic certainty. Gallus expressed his own misgivings concerning the trustworthiness of the royal story he passed on (he qualified it with words like "oblivion", "error" and "idolatry"), but the sequence of the last three names of Mieszko's predecessors he considered reliable.[88]

The results of archeological studies of the Greater Poland's 9th- and 10th-century gords are at odds with the timing of this story. There was no Gniezno settlement in the 9th century; there was a pagan cult site there beginning with the turn of the 10th century. The Gniezno gord was built around year 940, possibly because the location, being of great spiritual importance to the tribal community, would rally the local population around the building and defense effort.[89]

Early Piast state and its expansion

Under the old tribal system, the tribal assembly elected a chief in case of an external threat, to lead the defense effort, and it was a temporarily granted authority. The Piast clan was able to replace it in Gniezno area with its own hereditary rule over the tribe that inhabited it, which was in line with the trends of the times, and allowed them to create the state that they controlled. Greater Poland during the first half of the 10th century was not particularly densely populated or economically developed, lagging behind such regions as Pomerania, Silesia and Lesser Poland. It was favored by the above-mentioned geographic isolation, central location among the culturally similar tribes and extensive network of suitable for transportation rivers. What made the ultimate difference however could be that some Piast family members were exceptional individuals, able to take advantage of the arising opportunities.[90]

The development of the Piast state can be traced to some degree by following the disappearance of the old tribal gords (many of them were built in Greater Poland during the later part of the 9th century and soon thereafter), destroyed by the advancing Gniezno tribe people. For example, the gords in Spławie, Września County and in Daleszyn, Gostyń County, both built soon after 899, were attacked and taken over by the Piast state forces, the first one burned during the initial period of the armed expansion. The old gords were often rebuilt and enlarged or replaced, beginning in the first decades of the 10th century, by new, large and massively reinforced Piast gords. Gords of this type were erected or reconstructed from earlier ones initially in the tribe's native Gniezno Land and then elsewhere in central Greater Poland, in Grzybowo near Września (920–930),[91] Ostrów Lednicki, Giecz, Gniezno, Bnin in Poznań County, Ląd in Słupca County and in Poznań (Ostrów Tumski). Connected by water communication lines, in the mid-10th century the powerful gords served as the main concentrations of forces of the emerging state.[92]

In parallel with the gord building activity (920–950) the Piasts undertook military expansion, crossing the Warta and moving towards the end of this period south and west within the Oder River basin. The entire network of tribal gords between the Obra and Barycz rivers, among other places, was eliminated.[93][94] The conquered population was often resettled to central Greater Poland, which resulted in partial depopulation of previously well-developed regions. At the end of this stage of the Piast state formation new Piast gords were built in the (north) Noteć River area and other outlying areas of the annexed lands, for example in Santok and Śrem around 970. During the following decade the job of unifying the core of the early Piast state was finished—besides Greater Poland with Kujawy it included also much of central Poland. Masovia and parts of Pomerania found themselves increasingly under the Piast influence, while the southbound expansion was for the time being stalled, because large portions of Lesser Poland and Silesia were controlled by the Czech state.[95]

The expanding Piast state developed a professional military force. According to Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, Mieszko collected taxes in the form of weights used for trading and spent those taxes as monthly pay for his warriors. He had three thousands of heavily armored mounted soldiers alone, whose quality according to Ibrahim was very impressive. Mieszko provided for all their equipment and needs, even military pay for their children regardless of their gender, from the moment they were born. This force was supported by a much greater number of foot fighters.[96] Numerous armaments were found in the Piast gords, many of them of foreign, e.g. Frankish or Scandinavian origin. Mercenaries from these regions, as well as German and Norman knights, constituted a significant element of Mieszko's elite fighting guard.[97]

Revenue generating measures and conquests

To sustain this military machine and to meet other state expenses large amounts of revenue were necessary. Greater Poland had some natural resources used for trade such as fur, hide, honey and wax, but those surely did not provide enough income. According to Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, Prague in Bohemia, a city built of stone, was the main center for the exchange of trading commodities in this part of Europe. The Slavic traders brought here from Kraków tin, salt, amber and other products they had and most importantly slaves; Muslim, Jewish, Hungarian and other traders were the buyers. The Life of St. Adalbert, written at the end of the 10th century by John Canaparius, lists the fate of many Christian slaves, sold in Prague "for the wretched gold", as the main curse of the time.[98] Dragging of shackled slaves is shown as a scene in the bronze 12th-century Gniezno Doors. It may well be that the territorial expansion financed itself, and partially the expanding state, by being the source of loot, of which the captured local people were the most valuable part. The scale of the human trade practice is however arguable, because much of the population from the defeated tribes was resettled for agricultural work or in the near-gord settlements, where they could serve the victors in various capacities and thus contribute to the economic and demographic potential of the state. Considerable increase of population density was characteristic of the newly established states in eastern and central Europe. The slave trade not being enough, the Piast state had to look for other options for generating revenue.[98]

Thus, Mieszko throve to subdue Pomerania at the Baltic coast. The area was the site of wealthy trade emporia, frequently visited by traders, especially from the east, west and north. Mieszko had every reason to believe that great profits would have resulted from his ability to control the rich seaports situated on long distance trade routes, such as Wolin, Szczecin and Kołobrzeg.[99]

The Piast state reached the mouth of the Vistula first. Based on the investigations of the gords erected along the middle and lower Vistula, it appears that the lower Vistula waterway was under Piast control from about the mid-10th century. A powerful gord built in Gdańsk, under Mieszko at the latest, solidified the Piast rule over Pomerelia. However, the mouth of the Oder River was firmly controlled by the Jomsvikings and the Volinians, who were allied with the Veleti.[100] "The Veleti are fighting Mieszko", reported Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, "and their military might is great".[101] Widukind wrote about the events of 963, involving the person of the Saxon count Wichmann the Younger, an adventurer exiled from his country. According to Widukind, "Wichmann went to the barbarians (probably the Veleti or the Wolinians) and leading them (...) defeated Mieszko twice, killed his brother, and acquired a great deal of spoils".[101] Thietmar of Merseburg also reports that Mieszko with his people became in 963, together with other Slavic entities such as the Lusatians, subjects of the Holy Roman Emperor, forced into that role by the powerful Margrave Gero of the Saxon Eastern March.[101]

Mieszko's relationship with Emperor Otto I

Such series of military reverses and detrimental relationships, which also involved the Czech Přemyslids allied with the Veleti, compelled Mieszko to seek the support of the German Emperor Otto I. After the contacts were made, Widukind described Mieszko as "a friend of the Emperor".[101] A pact was negotiated and finalized no later than in 965. The price Mieszko had to pay for the imperial protection was becoming the Emperor's vassal, paying him tribute from the lands up to the Warta River, and, very likely, making a promise of accepting Christianity.[101]

Mieszko's acceptance of Christianity

In response to the immediate practical concerns, the Christian Church was installed in Poland in its Western Latin Rite.[h] The act brought Mieszko's country into the realm of the ancient Mediterranean culture. Of the issues requiring urgent attention the preeminent was the increasing pressure of the eastbound expansion (between the Elbe and the Oder rivers) of the German state, and its plans to control the parallel expansion of the Church through the archdiocese in Magdeburg, the establishment of which was finalized in 968.[87][102]

The baptism and the attendant processes did not take place through Mieszko's German connections. At that time Mieszko was in process of fixing the uneasy relationship with the Bohemian state of Boleslaus I. The difficulties were caused mainly by the Czech cooperation with the Veleti. Already in 964 the two parties arrived at an agreement on that and other issues.[103] In 965 Mieszko married Boleslaus' daughter Doubravka. Mieszko's chosen Christian princess, a woman possibly in her twenties,[104] was a devout Christian and Mieszko's own conversion had to be a part of the deal. This act in fact followed in 966 and initiated the Christianization of Greater Poland, a region up to that point, unlike Lesser Poland and Silesia, not exposed to Christian influence. In 968 an independent missionary bishopric, reporting directly to the Pope, was established, with Jordan installed as the first bishop.[105]

The scope of the Christianization mission in its early phase was quite limited geographically and the few relics that have survived come from Gniezno Land. Stone churches and baptisteries were discovered within the Ostrów Lednicki and Poznań gords, a chapel in Gniezno. Poznań was also the site of the first cathedral, the bishopric seat of Jordan and Bishop Unger, who followed him.[106]

Piast early expansion, Great Moravian and Norman contributions

Newer research points out some other intriguing possibilities regarding the early origins of the Polish state in Greater Poland. There are indications that the processes that led to the establishment of the Piast state began during the 890–910 period. During these years a tremendous civilizational advancement took place in central Greater Poland, as the unearthed products of all kinds are better made and more elaborate. The timing coincides with the breakdown of the Great Moravian state caused by the Magyar invasions. Before and after its 905–907 fall, fearing for their lives many Great Moravian people had to escape. According to the notes made by Constantine VII, they found refuge in the neighboring countries. Decorations found in Sołacz graves in Poznań have their counterparts in burial sites around Nitra in Slovakia. In Nitra area also there was in medieval times a well-known clan named Poznan. The above indicates that the Poznań town was established by Nitran refugees, and more generally, the immigrants from Great Moravia contributed to the sudden awakening of the otherwise remote and isolated Piast lands.[93]

Early expansion of the Gniezno Land tribe began very likely under Mieszko's grandfather Lestek, the probable real founder of the Piast state.[93] Widukind's chronicle speaks of Mieszko ruling the Slavic nation called "Licicaviki", which was what Widukind made out of "Lestkowicy", the people of Lestko, or Lestek. Lestek was also reflected in the sagas of the Normans, who may have played a role in Poland's origins (an accumulation of 930–1000 period treasures is attributed to them). Siemomysł and then Mieszko continued after Lestek, whose tradition was alive within the Piast court when Bolesław III Wrymouth gave this name to one of his sons and Gallus Anonymous wrote his chronicle.[93] The "Lechici" term popular later, synonymous with "Poles", like the legend of Lech, written in a chronicle at the turn of the 14th century, may also have been inspired by Mieszko's grandfather.[107]

Early capitals, large scale gord construction

There is some disagreement as to the early seat of the ruling clan. Modern archeology has shown that the gord in Gniezno had not even existed before about 940. This fact eliminates the possibility of Gniezno's early central role, which is what had long been believed, based on the account given by Gallus Anonymus. The relics (including a great concentration of silver treasures) found in Giecz, where the original gord was built some 80 years earlier, later turned into a powerful Piast stronghold, point to that location. Other likely early capitals include the old gords of Grzybowo, Kalisz (located away from Gniezno Land) or Poznań. Poznań, which is older than Gniezno, was probably the original Mieszko's court site in the earlier years of his reign. The first cathedral church, a monumental structure, was erected there. The events of 974–978, when Mieszko, like his brother-in-law Boleslaus II of Bohemia, supported Henry II in his rebellion against Otto II, created a threat of the Emperor's retribution. The situation probably motivated Mieszko to move the government to the safer, because of its more eastern location, Gniezno.[93] The Emperor's response turned out to be ineffective, but this geographical advantage continued in the years to come. The growing importance of Gniezno was reflected in the addition around 980 of the new southern part to the original two segments of the gord. In the existing summary of the Dagome iudex document written 991/992 before Mieszko's death, Mieszko's state is called Civitas Gnesnensis, or Gniezno State.[93]

The enormous effort of the estimated population of 100 to 150 thousands of residents of the Gniezno region, who were involved in building or modernizing Gniezno and several other main Piast gords (all of the local supply of oak timber was exhausted), was made in response to a perceived deadly threat, not just to help them pursue regional conquests. After 935, when the Gniezno people were probably already led by Mieszko's father Siemomysł, the Czechs conquered Silesia and soon moved also against Germany. The fear of desecration of their tribal cult center by the advancing Czechs could have mobilized the community.[93] Also a Polabian Slavs uprising was suppressed around 940 by Germany under Otto I, and the eastbound moving Saxons must have added to the sense of danger at that time (unless the Piast state was already allied with Otto, helping restrain the Polabians).[93] When the situation stabilized, the Piast state consolidated and the huge gords turned out to be handy for facilitating the Piast's own expansion, led at this stage by Siemomysł.[93]

Alliance with Germany and conquest of Pomerania

Fighting the Veleti from the beginning of Mieszko's rule led to an alliance of his state with Germany.[93] The alliance was natural at this point, because, as the Polish state was expanding westbound, the German state was expanding eastbound, with the Veleti in between being the common target. A victory was achieved in September of 967, when Wichmann, leading this time (according to Widukind) forces of the Volinians, was killed, and Mieszko, helped by additional mounted units provided by his father-in-law Boleslaus, had his revenge. Mieszko's victory was recognized by the Emperor as the turning point in the struggle to contain the Polabian Slavs, which distracted him from pursuing his Italian policies.[93] This new status allowed Mieszko to successfully pursue the efforts leading to obtaining by his country an independent bishopric. The Poles thus had their bishopric even before the Czechs, whose tradition of Christianity was much older.[93] The 967 victory, as well as the successful fighting with Margrave Hodo that followed in the Battle of Cedynia of 972, allowed Mieszko to conquer further parts of Pomerania. Wolin however remained autonomous and pagan. Kołobrzeg, where a strong gord was built around 985, was probably the actual center of Piast power in Pomerania.[108] Before, a Scandinavian colony in Bardy-Świelubie near Kołobrzeg functioned as the center of this area.[100] The western part of Mieszko controlled Pomerania (the region referred to by Polish historians as Western Pomerania, roughly within the current Polish borders, as opposed to Gdańsk Pomerania or Pomerelia), became independent of Poland during the Pomeranian uprising of 1005; that was after Mieszko's death, when Poland was ruled by his son Bolesław.[109][110][111]

Completion of Poland's territorial expansion under Mieszko

Around 980 in the west Lubusz Land was also under Mieszko's control and another important gord was built in Włocławek much further east. Masovia was still more loosely associated with the Piast state, while the Sandomierz region was for a while their southern outpost.[108]

The construction of powerful Piast gords in western Silesia region along the Oder River (Głogów, Wrocław and Opole) took place in 985 at the latest. The alliance with the Czechs was by that time over (Doubravka died in 977, leaving two children Bolesław and Świętosława), Mieszko allied with Germany fought the Přemyslids and took over that part of Silesia and then also eastern Lesser Poland, the Lendian lands. In 989 Kraków with the rest of Lesser Poland was taken over. The region, autonomous under the Czech rule, also enjoyed a special status within the Piast state.[75] In 990 eastern Silesia was added, which completed the Piast takeover of southern Poland. By the end of Mieszko's life, his state included the West Slavic lands in geographic proximity and connected by natural features, such as an absence of mountain ranges, to the Piast territorial nucleus of Greater Poland. Those lands have sometimes been regarded by historians as "Lechitic", or ethnically Polish, even though linguistically in the 10th century all the western Slavic tribes, including the Czechs, were quite similar.[9]

Silver treasures, common in the Scandinavian countries, are found also in Slavic areas including Poland, especially northern Poland. Silver objects, coins and decorations, often cut into pieces, are believed to have served as currency units, brought in by Jewish and Arab traders, but locally more as accumulations of wealth and symbols of prestige. The process of hiding or depositing them, besides protecting them from danger, is believed by the researchers to represent a cult ritual.[113]

A treasure located in Góra Strękowa, Białystok County, hidden after 901, includes dirhem coins minted between 764 and 901 and Slavic decorations made in southern Ruthenia, showing Byzantine influence. This find is a manifestation of a 10th-century trade route running all the way from Central Asia, through Byzantium, Kiev, the Dnieper and Pripyat rivers basins and Masovia, to the Baltic Sea shores. Such treasures most likely belonged to members of the emerging elites.[113][114]

See also

- Prehistory and protohistory of Poland

- Stone-Age Poland

- Bronze- and Iron-Age Poland

- Poland in Antiquity

- History of Poland during the Piast dynasty

Notes

a.^ "Though their names are now dispersed amid various clans and places, yet they are chiefly called Sclaveni and Antes" (Antes denoting the eastern early Slavic branch). Transl. by Charles Christopher Mierow, Princeton University Press 1908, from the University of Calgary web site.

b.^ Early Slavic peoples in Poland had their origins outside of Poland and arrived in Poland through migrations according to the allochthonic theory; according to the autochthonic theory the opposite is true, the Slavic or pre-Slavic peoples were present in Poland already in Antiquity or earlier

c.^ At about the time of the collapse of the Hun empire the Kiev culture ends its existence and the Kolochin, Penkovka and Prague-Korchak cultures are already well-established, so the Slavic expansion and differentiation had to take place in part within the Hun dominated areas

d.^ This article reflects the contemporary point of view of the Polish and East European archeologies. Many of the concepts presented were originally formulated by Kazimierz Godłowski of the Jagiellonian University. The idea of eastern origin of the Slavs was raised before him by J. Rozwadowski, K. Moszyński, H. Ułaszyn, H. Łowmiański (J. Wyrozumski – Historia Polski do roku 1505, p. 47, 63).

e.^ The Trzcinica site is being restored and developed as The Carpathian Troy Open-Air Archaeological Museum

f.^ The area is being developed as an outdoor replica of the settlement

g.^ Ibrahim ibn Yaqub wrote of four (Slavic) kings: The king of Bulgaria, Boleslaus the king of Prague, Bohemia and Kraków, Mieszko the king of the North, and Nako (of the Obotrites) the king of the West; Wyrozumski, p. 77

h.^ There is a minority opinion according to which Poland (or just southern Poland) was initially Christianized in the Slavic rite by followers of Cyril and Methodius and for a while the two branches coexisted in competition with each other. The arguments and speculations pointing in that direction were collected by Janusz Roszko in Pogański książę silny wielce (A pagan duke of great might), Iskry, Warszawa 1970

References

Inline

- 1 2 3 4 Piotr Kaczanowski, Janusz Krzysztof Kozłowski – Najdawniejsze dzieje ziem polskich (do VII w.) (Oldest History of Polish Lands (Till the 7th Century)), Fogra, Kraków 1998, ISBN 83-85719-34-2, p. 337

- 1 2 Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 327–330 and specifically 346

- ↑ For genetic evidence see Krzysztof Rębała et al. Y-STR variation among Slavs: evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin, in Journal of Human Genetics (Springer Japan), May 2007

- ↑ Byzantine historian Jordanes, Getica

- 1 2 Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, pp. 325–352

- 1 2 3 Various authors, ed. Marek Derwich and Adam Żurek, U źródeł Polski (do roku 1038) (Foundations of Poland (until year 1038)), Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, Wrocław 2002, ISBN 83-7023-954-4, p. 122-167

- 1 2 3 U źródeł Polski, pp. 142–143, Władysław Filipowiak

- 1 2 Truso by Marek Jagodziński of the Archeological-Historical Museum in Elbląg, from Pradzieje.pl web site

- 1 2 U źródeł Polski, pp. 162–163, Zofia Kurnatowska

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 334

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 232, 351

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Slavs and the Early Slav Culture by Michał Parczewski, Novelguide web site

- ↑ U źródeł Polski, pp. 125–126, Michał Parczewski

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 191, 212, 228–230, 232, 281

- 1 2 3 At the Source of the Slavic World, Michał Parczewski

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 243

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 277, 303

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski p. 334

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 281, 302, 303, 334, 351

- 1 2 U źródeł Polski, pp. 126, Michał Parczewski

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Getica, Transl. by Charles Christopher Mierow, Princeton University Press 1908, from the University of Calgary web site

- ↑ Sebastian Brather (2011-06-02). "The Western Slavs of the Seventh to the Eleventh Century – An Archaeological Perspective". History Compass. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 327, 334, 351

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 333, 334

- ↑ The web site of the Institute of Archeology, Jagiellonian University – Bachórz

- ↑ U źródeł Polski, p. 124, Michał Parczewski

- ↑ Kaczanowski, Kozłowski, p. 334–337

- ↑ U źródeł Polski, pp. 123–126, Michał Parczewski

- ↑ Słowianie nad Bzurą by Marek Dulinicz and Felix Biermann, Archeologia Żywa, issue 1 (16) 2001