Rishabhanatha

| Rishabhanatha | |

|---|---|

| First Tirthankara | |

|

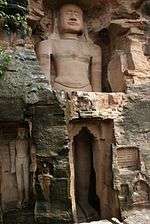

Image of Rishabhanatha at Kundalpur pilgrimage site in Madhya Pradesh, India | |

| Other names | Adinatha, Adish Jina (first conqueror), Adi Purush (first Perfect Man), Ikshvaku |

| Symbol | Bull[1] |

| Height | 500 bows (1500 metres)[2] |

| Age | 84 lakh purva (592.704 x 1018 years)[2] |

| Tree | Banyan |

| Color | Golden |

| Spouse | Sunanda and Sumangala |

| Parents | |

| Children |

Bharata Bahubali Sundari Brahmi |

| Succeeded by | Ajitanatha |

| Born | Ayodhya |

| Moksha | Mount Kailash |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major figures |

|

Major sects |

|

Festivals |

|

Pilgrimages |

|

|

Rishabhanatha also Ṛṣabhadeva or Rishabhadeva,[3] is the first Tirthankara (Teaching God) of the present half cycle of time in Jainism.[4][5] The word Tīrthankara signifies the founder of a tirtha which means a fordable passage across a sea. The Tirthankara show the 'fordable path' across the sea of interminable births and deaths (saṃsāra). Rishabhanatha is also known as Ādinātha which translates into "First (Adi) Lord (nātha)".

Jain cosmology divides the Worldly Time cycle into two halves (avasarpiṇī and utsarpiṇī) with six aras (spokes) in each half. Twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras grace this part of the universe in duşamā-suşamā (read as dukhmā-sukhmā) ara of both halves. The present half cycle (avasarpiṇī) being a special case, Rishabhanatha, the first tīrthaṅkara was born at the end of the third period (suṣama-duṣamā) itself.[6] According to Jain texts, he was born in the age when there was happiness all around with no work for men to do.[7] Gradually as the cycle moved, and wish-fulfilling trees disappeared, people rushed to their King for help.[8] Rishabhanatha is then said to have taught the men six main professions. These were: (1) Asi (swordsmanship for protection), (2) Masi (writing skills), (3) Krishi (agriculture), (4) Vidya (knowledge), (5) Vanijya (trade and commerce) and (6) Shilp (crafts).[5][9][10] In other words, he is credited with introducing karma-bhumi (the age of action) by teaching these professions to householders to enable them to earn a livelihood.[11][12][13] The institution of marriage came into existence after he married to set an example for other humans to follow.[14][12] In total, Rishabhanatha is said to have taught seventy-two sciences which include: arithmetic, the plastic and visual arts, the art of lovemaking, singing and dancing.[14] Jaina chronology places the date of Rishabhanatha at an almost immeasurable antiquity in the past.[15]

Founding of Jainism

Ṛṣabhanātha is said to be the founder of Jainism in the present half cycle,[16] and is unanimously considered to be so by the Jains. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the first Vice President of India wrote:

There is evidence to show that so far back as the first century B.C. there were people who were worshipping Ṛṣabhadeva, the first tīrthaṅkara. There is no doubt that Jainism prevailed even before Vardhamāna or Pārśvanātha. The Yajurveda mentions the name of three Tīrthaṅkaras - Ṛṣabha, Ajitnātha and Ariṣṭanemi. The Bhāgavata Purāṇa endorses the view that Ṛṣabha was the founder of Jainism.

Legends

-

Statuary representing Rishabhanatha's birth

-

Statuary representing Dance of Nilanjana

-

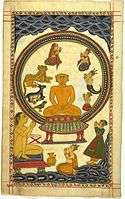

Statuary representing Samavasarana (divine preaching hall) of Rishabhanatha on Mount Kailash

Ādi purāṇa, a major Jain text records the life accounts of Rishabhanatha as well as ten previous lives.

Rishabhanatha is associated with his Bull emblem, the Nyagrodha tree, Gomukha (bull-faced) Yaksha, and Chakresvari Yakshi.[18]

Birth

Garbha kalyanaka is the first auspicious event out of five auspicious events (Panch Kalyanaka). It means enlivening of the embryo through the descent of the life (soul) in the mortal body. [19] On the second day of Ashadha (a month of the Hindu calendar) Krishna (dark fortnight), Queen Marudevi is said to have seen sixteen auspicious dreams. King Nabhi explained these dreams to her as a sign of Tirthankara's birth.

Rishabhanatha was born to King Nabhi and Queen Marudevi in Ayodhya, on the ninth day of the dark half of the month of Chaitra-caitra krişna navamĩ.[20] This is the second auspicious event and is known as Janma Kalyanaka.

Kingdom

Rishabhanatha's kingdom was kind and gentle and he is credited with transforming a tribal society into an orderly one.[21] Like all tīrthaṅkara and other legendary figures of Indian history who were great warriors, he too was one with great bodily strength. However, he never needed to show his warrior aspect.[14] Rishabhanātha is known for advocating non-violence,[14] and was one of the greatest initiators of human progress.[12]

Rishabhanatha had two wives, Sunanda and Sumangala.[22] Sumangala was the mother of ninety-nine sons (including Bharata) and one daughter, Brahmi.[23] Sunanda was the mother of Bahubali and Sundari.[24] He taught his daughters Brahmi and Sundari, the Brahmi-lipi (ancient Brahmi script) and the science of numbers (Ank-Vidya) respectively.[25] Rishabhanatha is said to have lived for 84 lakh (pūrva) of which 20 lakh pūrva were spent as a youth (kumāra kāla), and 63 lakh pūrva as the King (rājya kāla).[20]

Renunciation

One day Indra of the first heaven arranged a dance by celestial dancers in the assembly hall of Lord Rishabhanatha.[26] One of the dancers was Nilanjana, whose clock of life had only a few moments left to run.[20][27] While in the midst of a series of vigorous dance movements, she stopped, and the next instant her form 'dissolved' and she was no more.[28] The sudden fatal death of Nilanjana, reminded Rishabhanatha of the world's transitory nature and he developed a desire for renunciation.[26][28] He gave his kingdom to his hundred sons, of whom Bharata got the city of Vinita (Ayodhya) and Bahubali got the city of Podanapur (Taxila)[27] and became an ascetic on the ninth day of the month of Chaitra Krishna (Hindu calendar). The renunciation is the third of Panch Kalyanaka and is called Diksha Kalyanaka.[29]

Akshaya Tritiya

Akshaya Tritya is considered holy and supremely auspicious by Jains. It is believed that Rishabhanatha took his first ahara (alms) as an ascetic on this day. Rishabhanatha was the first monk of the present half cycle of time (avasarpini).[30] Therefore, people did not knew how to offer food (ahara) to Digambara monks. King Shreyansa of Hastinapur town recollected his past life experiences and offered sugarcane juice (ikshu-rasa) to Rishabhanatha.[31] Jains attach great importance to this day as it was only after 6 months that Rishabhanatha was offered food. It is celebrated on the third day of the bright fortnight of the month Vaishaka.[32] He got the name Ikshvaku[12] from the word Ikhsu (sugarcane)[33] and his dynasty became Ikshvaku dynasty.[34]

Omniscience

Rishabhanatha spent a thousand years performing austerities and then attained Kevala Jnana (omniscience) on the eleventh day of Falgun Krishna (Hindu calendar) under a banyan tree.[35] According to Jain texts, Devas (heavenly beings) created a divine preaching hall known as samavasarana. This is the fourth of Panch Kalyanaka and is known as Kevala Jnāna Kalyanaka. According to Jain texts, the following is the number of followers of Tirthankara Rishabhanatha:[36]

- Eighty-four Ganadharas (apostles)

- Twenty-thousand Omniscient saints.

- 12,700 saints endowed with Telepathy[37]

- Nine-thousand saints with clairvoyance.

- 4,750 saints śrut-kevali (saints having complete knowledge of Jain Agamas)

- 20,600 saints with miraculous powers.

- Three hundred and fifty thousand nuns, headed by Brahmi.[38]

- Three hundred thousand householders.

As an Omniscient, Tirthankara Rishabhanatha is said to have preached, for 1 lakh pūrva less thousand years (kevalakāla).[28]

Moksha

Rishabhanatha is said to have preached Jainism far and wide.[39] He attained Moksha (liberation from the cycle of births and deaths) at Ashtapada (famously known as Mount Kailash)[39] on the fourteenth day of Magha Krishna (Hindu Calendar) at the age of 84 lakh purva (592.704 x 1018 years).[2] His preachings were recorded in fourteen scriptures known as Purvas.[40]

In literature

There is mention of Rishabhanatha in Hindu scriptures, like the Rigveda, Vishnu Purana and Bhagavata Purana.[41][42]

Rishabhanatha is also mentioned in Buddhist literature. It speaks of several tirthankara and includes Rishabhanatha along with: Padmaprabha, Chandraprabha, Pushpadanta, Vimalanatha, Dharmanatha, and Neminatha. A Buddhist scripture named Dharmottarapradipa mentions Rishabhanatha as an Apta (Tirthankara).[23]

The "Ādi purāṇa", a 9th-century Sanskrit poem,[43] and a 10th-century Kannada commentary on it by the poet Adikavi Pampa (fl. 941 CE), written in Champu style, a mix of prose and verse and spread over sixteen cantos, deals with the ten lives of Rishabhanatha and his two sons.[44][45] The life of Rishabhanatha is also detailed in Mahapurana of Jinasena, Trisasti-salaka-purusa-caritra by the scholar Hemachandra, Kalpa Sutra a Jain text containing the biographies of the Jain Tirthankaras, and Jambudvipa-prajnapti.[42][46]

Bhaktamara Stotra by Acharya Manatunga is one of the most prominent prayers mentioning Rishabhanatha.[47]

Iconography

Rishabhanatha is usually depicted in the lotus position or kayotsarga, a standing posture of meditation. The distinguishing features of Rishabhanatha is his long locks of hair which fall on his shoulders, and an image of a bull in sculptures of him.[48] Paintings of him usually depict legendary events of his life. Some of these include his marriage, and Indra performing a ritual known as abhisheka. He is sometimes shown presenting a bowl to his followers and teaching them the art of pottery, painting a house, or weaving textiles. The visit of his mother Marudevi is also shown extensively in painting.[49]

Images

-

)%2C_Parshvanatha%2C_Neminatha%2C_and_Mahavira)_LACMA_M.85.55_(1_of_4).jpg)

Shrine with Four Jinas Rishabhanatha, Parshvanatha, Neminatha, and Mahavira at LACMA, 6th century

-

Idol of Rishabhanatha at Mathura Museum, Uttar Pradesh (Circa 6th Century CE)

-

Image depicting Rishabhanatha, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 7th century

-

Image depicting Rishabhanatha (Maharaja Chhatrasal Museum) dated 10th century

-

Rishabhanatha, sandstone, Chandela period, Guimet Museum, 10th-11th century

-

Rishabhanatha idol from Gurupura at Shivappa Nayaka palace, Shivamogga, 12th century

-

Rishabhanatha with 23 additional Jinas, Ethnological Museum of Berlin, 12th century

-

Kalchuri period Adinath image at Hanumantal Bada Jain Mandir, Jabalpur

Colossal statues

-

Statue of Ahimsa, Maharashtra, 108 feet (33 m)

-

Bawangaja, Madhya Pradesh, 84 feet (26 m)

-

Siddhachal Jain Temple, Gopachal Hill, Madhya Pradesh, 58.4 feet (17.8 m)

Temples

- Palitana Jain Temple

- Kulpakji Jain Temple

- Vataman Jain Temple

- Kundalpur Jain Temple

- Bibrod Tirth

- Paporaji Jain Temple

- Rishabhdeo Jain Temple

- Adinath Digambara Jain Temple, Ladnu, Rajasthan

-

Nasiyan Ji Jain temple, Ajmer

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rishabhanatha. |

Citations

- ↑ Shanti Lal Jain 1998, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 Sarasvati 1970, p. 444.

- ↑ Vilas Adinath Sangave, Facets of Jainology, Popular Prakashan, 2001, p. 131.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 208-09.

- 1 2 Shanti Lal Jain 1998, p. 47.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. xiv.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 78.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 88.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. x.

- ↑ Sangave 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 5.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 4 Rankin 2010, p. 43.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. xv.

- ↑ Sangave 2001, p. 131.

- ↑ S. Radhakrishnan. Indian Philosophy. The Macmillan Company. p. 287.

- ↑ Tandon 2002, p. 44.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 195.

- 1 2 3 Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 181.

- ↑ Rankin 2010, p. 43–44.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 64–66.

- 1 2 Sangave 2001, p. 105.

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 112.

- ↑ Shanti Lal Jain 1998, p. 47–48.

- 1 2 Cort 2010, p. 25.

- 1 2 Titze 1998, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 182.

- ↑ Rankin 2010, p. 44.

- ↑ B.K. Jain 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 86.

- ↑ Titze 1998, p. 138.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 76–77.

- ↑ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 15.

- ↑ Krishna & Amirthalingam 2014, p. 46.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 126–127.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 126.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 127.

- 1 2 Cort 2010, p. 115.

- ↑ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Staff, Rao; Raghunadha Rao (1989). Indian Heritage and Culture. p. 13. ISBN 978-81-207-0930-0.

- 1 2 Jaini 2000, p. 326.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 26.

- ↑ "Kamat's Potpourri: History of the Kannada Literature -II". kamat.com.

- ↑ Students' Britannica India, Volumes 1-5, Popular Prakashan, 2000, p. 78, ISBN 0-85229-760-2

- ↑ Gupta 1999, p. 133.

- ↑ "Shri Bhaktamara Mantra (भक्तामर स्त्रोत)".

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 113.

- ↑ Jain & Fischer 1978, p. 16.

References

- Cort, John E. (2010) [1953], Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Gupta, Gyan Swarup (1999), India: From Indus Valley Civilisation to Mauryas, Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 978-81-7022-763-2

- Jain, Babu Kamtaprasad (2013), Digambaratva aur Digambar muni, Bharatiya Jnanpith, ISBN 81-263-5122-5

- Jain, Champat Rai (1929), Risabha Deva - The Founder of Jainism, Allahabad: The Indian Press Limited,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Jyotindra; Fischer, Eberhard (1978), Jaina iconography, ISBN 90-04-05260-7

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahavira and his times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Jain, Shanti Lal (1998), ABC of Jainism, Bhopal (M.P.): Jnanodaya Vidyapeeth, ISBN 81-7628-000-3

- Jain, Vijay K. (2015), Acarya Samantabhadra's Svayambhustotra: Adoration of The Twenty-four Tirthankara, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-7-6,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2000), Collected Papers on Jaina Studies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1691-9

- Krishna, Nanditha; Amirthalingam, M. (2014) [2013], Sacred Plants of India, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-93-5118-691-5

- Rankin, Aidan (2010), Many-Sided Wisdom: A New Politics of the Spirit, John Hunt Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84694-277-8

- Sangave, Dr. Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-839-3

- Sarasvati, Swami Dayananda (1970), An English translation of the Satyarth Prakash, Swami Dayananda Sarasvati

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1938-1

- Shah, Umakant P. (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-208-X

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Tandon, Om Prakash (2002) [1968], Jaina Shrines in India (1 ed.), New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, ISBN 81-230-1013-3

- Titze, Kurt (1998), Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Joseph Campbell, ed., Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.