Sino-Sikh War

| Sino-Sikh war | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

General Zorawar Singh (1786-1841) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Meng Bao Haipu | Zorawar Singh Kahluria † | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

| Sino-Sikh War | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 森巴戰爭 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 森巴战争 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Dogra War | ||||||

| |||||||

The Sino-Sikh War (also referred to as the Invasion of Tibet or the Dogra War) was fought from May 1841 to August 1842, between the forces of Qing China and the Sikh Empire after General Zorawar Singh Kahluria invaded western Tibet.[1] At the time of the war, the Dogra dynasty was a vassal of the Sikh Empire, and so the conflict is also known as the Dogra War. The Sikh army was routed and the Qing counterattacked but were defeated in Ladakh resulting in an overall military stalemate. The Treaty of Chushul was signed in 1842 maintaining the status quo ante bellum.

Background

From the early 18th century, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty had consolidated its control of Tibet after defeating the Dzungar Khanate. From then until late into the 19th century, the Qing rule of the region remained unchallenged. South of the Himalayas, Ranjit Singh established his empire in the Punjab region in 1799.

In 1808, Ranjit Singh conquered Jammu, which was under control of the Hindu Rajput Dogra dynasty from Dougar Desh in Jammu[2] and incorporated them into his empire as vassals.

Historians continue to debate the reasons for the invasion; some say control of Tibet would have given Gulab Singh a monopoly on the lucrative pashmina wool trade of Tibet, others believe that he aimed to establish a land bridge between Ladakh and Nepal to create a Sikh-Gorkha alliance against the British.[3] However, Zorawar Singh Kahluria was only conquering lands which were distinctly foreign areas which had a rich indigenous Indian civilization to the marauding Tibetans from the East. According to Rolf Alfred Stein, author of Tibetan Civilization, the area of Shang Shung comprising the area conquered by Zorawar Singh Kahluria was not historically a part of Tibet and was a distinctly foreign territory to the Tibetans. According to Rolf Alfred Stein,[4] “…Then further west, The Tibetans encountered a distinctly foreign nation. - Shangshung, with its capital at Khyunglung. Mt. Kailāśa (Tise ) and Lake Manasarovar formed part of this country., whose language has come down to us through early documents. Though still unidentified, it seems to be Indo European. …Geographically the country was certainly open to India, both through Nepal and by way of Kashmir and Ladakh. Kailāśa is a holy place for the Indians, who make pilgrimages to it. No one knows how long they have done so, but the cult may well go back to the times when Shangshung was still independent of Tibet. How far Shangshung stretched to the north , east and west is a mystery…. We have already had an occasion to remark that Shangshung, embracing Kailāśa sacred Mount of the Hindus, may once have had a religion largely borrowed from Hinduism. The situation may even have lasted for quite a long time. In fact, about 950, the Hindu King of Kabul had a statue of Vişņu, of the Kashmiri type (with three heads), which he claimed had been given him by the king of the Bhota (Tibetans) who, in turn had obtained it from Kailāśa.”

A chronicle of Ladakh compiled in the 17th century called the La dvags rgyal rabs, meaning the Royal Chronicle of the Kings of Ladakh recorded that this boundary was traditional and well-known. The first part of the chronicle was written in the years 1610 -1640, and the second half towards the end of the 17th century. The work has been translated into English by A. H. Francke and published in 1926 in Calcutta titled the “Antiquities of Indian Tibet” . In volume 2, the Ladakhi Chronicle describes the partition by King Sykid-Ida-ngeema-gon of his kingdom between his three sons, and then the chronicle described the extent of territory secured by that son. The following quotation is from page 94 of this book: "He gave to each of his sons a separate kingdom, viz., to the eldest Dpal-gyi-ngon, Maryul of Mnah-ris, the inhabitants using black bows; ru-thogs of the east and the Gold-mine of Hgog; nearer this way Lde-mchog-dkar-po; at the frontier ra-ba-dmar-po; Wam-le, to the top of the pass of the Yi-mig rock…..” From a perusal of the aforesaid work, it is obvious and evident that Rudokh was an integral part of Ladakh, and even after the family partition Rudokh continued to be part of Ladakh. Maryul meaning lowlands was a name given to a part of Ladakh. Even at that time, i.e. in the 10th century, Rudokh was an integral part of Ladakh and Lde-mchog-dkar-po, i.e. Demchok was also an integral part of Ladakh.

The capital city of Zhang Zhung was called Khyunglung (Khyunglung Ngülkhar or Khyung-lung dngul-mkhar), the "Silver Palace of Garuda", southwest of Mount Kailash (Mount Ti-se), which is identified with palaces found in the upper Sutlej Valley.[5]

The Zhang Zhung built a towering fort, Chugtso Dropo, on the shores of sacred Lake Dangra, from which they exerted military power over the surrounding district in central Tibet.

The fact that some of the ancient texts describing the Zhang Zhung kingdom also claimed the Sutlej valley was Shambhala, the land of happiness (from which James Hilton possibly derived the name "Shangri La"), may have delayed their study by Western scholars.

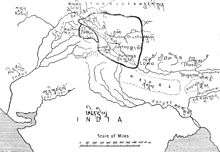

Zorawar Singh knew that western Tibet (Ngari) was connected to the rest of Tibet by the Mayum La, so his plan consisted of advancing as quickly as possibly into enemy territory, capturing the pass before winter, and building up his forces for a renewed campaign in the summer.[6]

Invasion of Tibet

As Zorawar Singh had done in Ladakh, so too in the newly conquered Baltistan, Zorawar recruited the Baltis into his army, which now had men from the Jammu hills, Kishtwar, and Ladakh. This five or six thousand-strong army was divided into three columns that marched parallel into Tibet in May 1841.

One column under the Ladakhi prince Nono Sungnam followed the course of the Indus River to its source at Lake Manasarovar. Another column of 300 men under Ghulam Khan marched along the mountains leading up to the Kailash Range south of the Indus. Zorawar himself led 3000 men along the plateau region where the vast and picturesque Pangong Tso is located. The invaders met with success in the beginning of the invasion, thanks to the quality of their weapons, but the Tibetans resisted using guerrilla tactics and their knowledge of the local terrain.[7]

Sweeping all resistance before them, the three columns passed Lake Manasarovar and converged at Gartok, defeating the small Tibetan force stationed there. The enemy commander fled to Taklakot but Zorawar stormed that fort on September 6, 1841. Envoys from Tibet now came to him as did agents of the Maharaja of Nepal, whose kingdom was only fifteen miles from Taklakot.

The Sikh army now controlled the urban centers of Daba, Tholing, Tsaparang Rudok, Gartok and Taklakot (modern Burang Town).[8] He garrisoned the towns and set up an administration to rule the occupied territories. Meanwhile, in the Punjab, the British envoys pressured the Maharaja to order his withdrawal while the Nepalis helped the Qing forces against him.[8]

The fall of Taklakot finds mention in the report of the Chinese Imperial Resident, Meng Pao, at Lhasa:

On my arrival at Taklakot a force of only about 1,000 local troops could be mustered, which was divided and stationed as guards at different posts. A guard post was quickly established at a strategic pass near Taklakot to stop the invaders, but these local troops were not brave enough to fight off the Shen-Pa (Dogras) and fled at the approach of the invaders. The distance between Central Tibet and Taklakot is several thousand li…because of the cowardice of the local troops; our forces had to withdraw to the foot of the Tsa Mountain near the Mayum Pass. Reinforcements are essential in order to withstand these violent and unruly invaders.

Zorawar and his men went on pilgrimage to Mansarovar and Mount Kailash. He had extended his communication and supply line over 450 miles of inhospitable terrain by building small forts and pickets along the way. The fort Chi-T’ang was built near Taklakot, where Mehta Basti Ram was put in command of 500 men, with 8 or 9 cannon. With the onset of winter all the passes were blocked and roads snowed in. The supplies for the Dogra army over such a long distance failed despite Zorawar’s meticulous preparations.

As the intense cold, coupled with the rain, snow and lightning continued for weeks upon weeks, many of the soldiers lost their fingers and toes to frostbite. Others starved to death, while some burnt the wooden stock of their muskets to warm themselves. The Tibetans and their Han Chinese allies regrouped and advanced to give battle, bypassing the Dogra fort of Chi-T’ang. Zorawar and his men met them at the Battle of Toyo on December 12, 1841. In the early exchange of fire the Rajput general was wounded in his right shoulder, but he grabbed a sword in his left hand. The Tibetan horsemen then charged the Dogra position and one of them thrust his lance in Zorawar Singh’s chest. Wounded and unable to escape he was pulled down off his horse and beheaded.[7] The battle marked the end of the invasion, with the death of their general and 300 dead and 700 soldiers captured,[7] the army of Punjab hurriedly retreated to Ladakh with the Sino-Tibetan forces on their heels until they finally halted the pursuit just a day from Leh.[9]

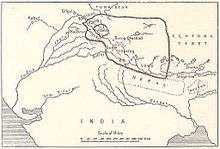

Qing invasion of Ladakh

The Sino-Tibetan force then mopped up the other garrisons of the Dogras and advanced on Ladakh, now determined to conquer it and add it to the Imperial Chinese dominions. However the force under Mehta Basti Ram withstood a siege for several weeks at Chi-T’ang before escaping with 240 men across the Himalayas to the British post of Almora. Within Ladakh the Sino-Tibetan army laid siege to Leh, when reinforcements under Diwan Hari Chand and Wazir Ratnu came from Jammu and repulsed them. The Tibetan fortifications at Drangtse were flooded when the Dogras dammed up the river. On open ground, the Chinese and Tibetans were chased to Chushul. The climactic Battle of Chushul (August 1842) was won by the Dogras who executed the enemy general to avenge the death of Zorawar Singh.

The Treaty of Chushul

At this point, neither side wished to continue the conflict, as the Sikhs were embroiled in tensions with the British that would lead up to the First Anglo-Sikh War, while the Qing were in the midst of the First Opium War with the East India Company. Qing China and the Sikh Empire signed a treaty in September 1842 that stipulated no transgressions or interference in the other country's frontiers.[10]

"As on this auspicious day, the 3nd of Assuj, samvat 1899 (16th/17th September 1842) we, the officers of the Lhasa (Governrnent), Kalon of Sokan and Bakshi Shajpuh, commander of the forces, and two officers on behalf of the most resplendent Sri Khalsa ji Sahib, the asylum of the world, King Sher Singh ji, and Sri Maharaja Sahib Raja-i-Rajagan Raja Sahib Bahadur Raja Gulab Singh, i.e.. the Muktar-ud-Daula Diwan Hari Chand and the asylum of vizirs, Vizir Ratnun. in a meeting called together for the promotion of peace and unity, and by professions and vows of friendship, unity and sincerity of heart and by taking oaths like those of Kunjak Sahib, have arranged and agreed that relations of peace, friendship and unity between Sri Khalsaji and Sri Maharaja Sahib Bahadur Raja Gulab Singh ji, and the Emperor of China and the Lama Guru of Lhasa will hence forward remain firmly established forever; and we declare in the presence of the Kunjak Sahib that on no account whatsoever will there be any deviation, difference of departure (from this agreement). We shall neither at present nor in the future have anything to do or interfere at all with the boundaries of Ladakh and its surroundings as fixed from ancient times and will allow the annual export of wool, shawls and tea by way of ladakh according to the old established customs.Should any of the Opponents of Sri Sarkar Khalsa ji and Sri Raja Sahib Bahadur at any time enter our territories, we shall not pay any heed to his words or allow him to remain in our country. We shall offer no hindrance to traders of Ladakh who visit our territories. We shall not even to the extent of a hair's breadth act in contravention of the terms that we have agreed to above regarding firm friendship, unity, the fixed boundaries of Ladakh and the keeping open of the route for wool, shawls and tea. We call Kunjak Sahib, Kairi, Lassi, Zhon Mahan, and Khushal Chon as witnesses to this treaty."[10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Dattar, C. L. "ZORĀWAR SIṄGH (1786-1841)". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjabi University Patiala.

- ↑ Heath 2005, p. 35

- ↑ Bakshi 2002, p. 96

- ↑ Tibetan Civilization by R.A. Stein Faber and Faber

- ↑ Allen, Charles. (1999). The Search for Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History. Abacus Edition, London. (2000), pp. 266-267; 273-274. ISBN 0-349-11142-1.

- ↑ Bakshi 2002, p. 97

- 1 2 3 Maher;Shakabpa 2010, p. 577

- 1 2 McKay 2003, p. 28

- ↑ Maher;Shakabpa 2010, p. 584

- 1 2 The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan., 1960), pp. 96-125.

References

- Heath, Ian (2005). The Sikh Army 1799-1849. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-777-8.

- Maher, Derek F.; Shakabpa, W. D. (2010). One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet. 1. BRILL. ISBN 9789004177888.

- McKay, Alex (2003). History of Tibet. Routledge. ISBN 9780700715084.

- Bakshi, G. D. (2002). Footprints in the snow: on the trail of Zorawar Singh. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 9788170622925.