South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club

|

South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club Historic District | |

|

Clubhouse, August 2012 | |

| |

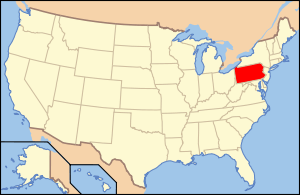

| Location | Roughly bounded by Fourtieth, Main, and Lake Sts., Adams Township, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°20′17″N 78°46′24″W / 40.33806°N 78.77333°WCoordinates: 40°20′17″N 78°46′24″W / 40.33806°N 78.77333°W |

| Area | 5.6 acres (2.3 ha) |

| Built | 1883 |

| Architectural style | Stick/eastlake, Gothic, Queen Anne |

| NRHP Reference # | 86002091[1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 31, 1986 |

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was a Pennsylvania corporation which operated an exclusive and secretive retreat at a mountain lake near South Fork, Pennsylvania for more than fifty extremely wealthy men and their families. The club was the owner of the South Fork Dam, which failed during an unprecedented period of heavy rains, resulting in the disastrous Johnstown Flood on May 31, 1889.

The failure released an estimated 20 million tons of water from Lake Conemaugh, wreaking devastation along the valley of South Fork Creek and the Little Conemaugh River as it flowed about a dozen miles downstream to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where the confluence of the Little Conemaugh and Stonycreek River forms the Conemaugh River, a tributary of the Allegheny River.

It was the worst disaster event in U.S. history at the time, and relief efforts were among the first major actions of Clara Barton and the newly organized American Red Cross which she led. The death toll from the 1889 flood was approximately 2,209, about 1/3 of whom were individuals who were never identified.

Despite some years of claims and litigation, the club and its members were never found to be liable for monetary damages. The corporation was disbanded in 1904 and the real estate assets were sold by the local sheriff at public auction, largely to satisfy a pre-existing mortgage on the large clubhouse.

Dam and club history

The South Fork Dam was originally built between 1838-1853 by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania as part of the Pennsylvania Main Line canal system to be used as a reservoir for the canal basin in Johnstown. It was abandoned by the commonwealth, sold to the Pennsylvania Railroad, and then sold again to private interests.

In 1879, at the suggestion of entrepreneur Benjamin Franklin Ruff, the newly organized club purchased an old dam and abandoned reservoir from Ruff which he had purchased from Congressman John Reilly. Ruff envisioned a summer retreat in the hills above Johnstown. He promoted this idea to Henry Clay Frick, a friend of his, who was one of the wealthy elite group of powerful men who controlled Pittsburgh's steel, rail and other industries,

Lake Conemaugh, which was about two miles (3 km) long, approximately one mile (1.6 km) wide, and 60 feet (18 m) deep near the dam, was named by the new club. The lake had a perimeter of 7 miles (11 km) and could hold 20 million tons of water. When the water was "up" in the spring, the lake covered over 400 acres (1.6 km²). The South Fork Dam was 72 feet (22 m) high and 931 feet (284 m) long. It failed for the first time in 1862, and although well-designed and built when new, by a history of negligent maintenance and alterations which later were believed to have contributed to its failure on May 31, 1889. Between 1881 when the club was opened and 1889, this dam frequently sprang leaks and was patched, mostly with mud and straw.

Major flaws regarding the dam

Prior to closing on Ruff's purchase, Congressman Reilly had crucial discharge pipes removed and sold for their value as scrap steel, so there was no practical way to lower the level of water behind the dam should repairs be indicated.[2] Ruff, while he was not a civil engineer, had a background that included being a railroad tunnel contractor and supervised the repairs to the dam, which did not include a successful resolution of the inability to discharge the water and substantially lower the lake for repair purposes.[2]

The 3 cast iron discharge pipes had previously allowed a controlled release of water. When the initial renovation was completed under Ruff's oversight, it was now impossible to drain the lake to repair the dam properly. Moreover, in order to provide a carriageway across the dam, the top was leveled off, lowering it, leaving it only a few feet above the water level at its lowest point. To compound the problem, the owners and managers had erected fish screens across the mouth of the spillway, and these became clogged with debris, restricting the outflow of water.

Over the years, despite dire predictions of some, the dam had not failed completely since 1862. Notwithstanding leaks and other warning signs, the flawed dam held the waters of Lake Conemaugh back more or less successfully until disaster struck in May 1889.

The many years of false alarms may have contributed to the failure of anyone in Johnstown to take any serious action despite repeated warnings of imminent failure telegraphed by club personnel on May 31, 1889, following days of an unprecedented rainfall in the entire region. The president at the time of the flood was Colonel Elias Unger.[3] The founding entrepreneur, Benjamin F. Ruff, had died several years earlier, and Unger had been on the job only a short time.

Club members

The charter members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, assembled by Henry Clay Frick were: Benjamin Ruff; T. H. Sweat; Charles J. Clarke; Thomas Clark; Walter F. Fundenberg; Howard Hartley; Henry C. Yeager; J. B. White; E. A. Myers; C. C. Hussey; D. R. Ewer; C. A. Carpenter; W. L. Dunn; W. L. McClintock; A. V. Holmes.

Alphabetically, a complete listing of club membership included:[3]

- Edward Jay Allen - helped to organize the Pacific and Atlantic Telegraph Company

- D.W.C Bidwell - owner of a mining industry explosives supply company

- James W. Brown - member of the 58th United States Congress, president of the Colonial Steel Company, and secretary and treasurer for Hussey, Howe and Company, Steel Works, Ltd.

- Hilary B. Brunot - attorney in Pittsburgh

- John Caldwell, Jr. - treasurer of the Philadelphia Company

- Andrew Carnegie - Scottish-American industrialist, businessman, entrepreneur and a major philanthropist

- C.A. Carpenter - freight agent for the Pennsylvania Railroad

- John Weakley Chalfant - president of People's National bank, associated with steel tubing manufacturer Spang, Chalfant and Company

- George H. Christy - attorney in Pittsburgh

- Thomas Clark

- Charles John Clarke - founder of Pittsburgh-based transportation company Clarke and Company, father of Louis Clarke

- Louis Semple Clarke - co founder of the Autocar Company and developer of the first porcelain-insulated spark plugs

- A.C. Crawford

- William T. Dunn - owner of the building supply company William T. Dunn and Company

- Cyrus Elder - attorney and chief counsel for the Cambria Iron Company

- Daniel R. Euwer - lumber dealer for Euwer and Brothers

- John King Ewing - involved with real estate through Ewing and Byers

- Aaron S. French - founder of A. French Spring Company, manufacturer of steel springs for railroad cars

- Henry Clay Frick - successful American industrialist and art patron

- Walter Franklin Fundenburg - dentist

- A. G. Harmes - manufacturer of machinery through his Harmes Machinery Depot

- John A. Harper - assistant cashier of the Bank of Pittsburgh, president of Western Pennsylvania Hospital

- Howard Hartley - manufacturer of leather products and rubber belts through Hartley Brothers

- Henry Holdship - co founder of the Art Society of Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

- Americus Vespecius Holmes - vice-president of Dollar Bank

- Durbin Horne - president of retail company Joseph Horne and Company

- George Franklin Huff - member of the Pennsylvania State Senate from 1884 to 1888, member of the 52nd United States Congress, the 54th United States Congress, and the 58th United States Congress and the three succeeding Congresses

- Christopher Curtis Hussey - Hussey, Howe and Company, steel manufacturers

- Lewis Irwin

- Philander Chase Knox - American lawyer and politician who served as Attorney General and U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania and was Secretary of State from 1909–1913

- Frank B. Laughlin - secretary of the Solar Carbon and Manufacturing Company

- John Jacob Lawrence - paint and color manufacturer, partner of Moses Suydam

- John George Alexander Leishman - worked in various executive positions at Carnegie Steel Company, served as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Turkey from 1899–1901

- Jesse H. Lippincott - associated with the Banner Baking Powder firm

- Sylvester Stephen Marvin - established himself in the cracker business, founding S. S. Marvin Co., centerpiece to the organization of the National Biscuit Company)

- Frank T., Oliver, and Walter L. McClintock - associated with O. McClintock and Company, a mercantile house

- James S. McCord - owner of the wholesale hatters McCord and Company

- James McGregor

- W. A. McIntosh (president of the New York and Cleveland Gas Coal Company and father of Burr McIntosh and Nancy McIntosh)

- H. Sellers McKee - president of the First National Bank of Birmingham, founder of Jeannette, Pennsylvania

- Andrew W. Mellon - American banker, industrialist, philanthropist, art collector and Secretary of the Treasury from March 4, 1921 until February 12, 1932

- Reuben Miller - Miller, Metcalf and Perkin, Crescent Steel Works

- Maxwell K. Moorhead - son of James K. Moorhead

- Daniel Johnson Morrell - general manager of the Cambria Iron Company, member of the 40th United States Congress and 41st United States Congresses

- William Mullens

- Edwin A. Meyers - Myers, Shinkle and Company

- H. P. Patton - associated with the window glass manufacturer A. and D. H. Chambers

- Duncan Clinch Phillips - window glass millionaire, father of Duncan Phillips

- Henry Phipps, Jr. - chairman of Carnegie Brothers and Company, American entrepreneur and major philanthropist

- Robert Pitcairn - Scottish-American railroad executive who headed the Pittsburgh Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad in the late 19th century

- D. W. Ranking - physician

- Samuel Rea - an American engineer and the 9th president of the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1913–25

- James Hay Reed - partner with Philander Knox in the law firm Knox and Reed, a federal judge nominated by President Benjamin Harrison

- Benjamin F. Ruff - first president of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, tunnel contractor, coke salesman, real estate broker

- Marvin F. Scaife - producer of iron products through W. B. Scaife and Sons

- James M. Schoonmaker - J. M. Schoonmaker Coke Company

- James Ernest Schwartz - president of Pennsylvania Lead Company

- Frank Semple

- Christian Bernard Shea - member of Joseph Horne and Company

- Moses Bedell Suydam - M. B. Suydam and Company

- F. H. Sweet

- Benjamin Thaw - co founder of Heda Coke Company, brother of Harry Kendall Thaw

- Colonel Elias J. Unger - managed hotels along the Pennsylvania Railroad, second and last president of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, did not have a military record

- Calvin Wells - president of Pittsburgh Forge and Iron Company. Nephew of Samuel Taggart who served as a US Representative from Massachusetts from 1754 to 1825.

- James B. White - manufacturer of manganese ore through James B. White and Company

- John F. Wilcox - civil engineer

- James H. Willock - cashier of the Second National Bank

- Joseph R. Woodwell - served on the board of directors for Deposit Bank of Pittsburgh and the Carnegie Institution for Science

- William K. Woodwell - associated with Joseph R. Woodwell and company

- H. C. Yeager - dry goods and trimming wholesaler through C. Yeager and Company

The flood

After several days of unprecedented rainfall in the Alleghenies, the dam gave way on May 31, 1889. A torrent of water raced downstream, destroying several towns. When it reached Johnstown, just under 2,200 people were killed, and there was $17 million in damage. The disaster became widely known as the Johnstown Flood, and locally known as the "Great Flood".

Rumors of the dam's potential for harm, and its likelihood of bursting had been circulating for years, and perhaps this contributed to why they were not taken seriously on that fateful day. For whatever reason, at least three warnings sent from South Fork to Johnstown by telegram the day of the disaster went virtually unheeded downstream.

When word of the dam's failure was telegraphed from South Fork by Joseph P. Wilson to Robert Pitcairn in Pittsburgh, Frick and other members of the Club gathered to form the Pittsburgh Relief Committee for tangible assistance to the flood victims as well as determining to never speak publicly about the Club or the Flood. This strategy was a success, and Knox and Reed were able to fend off all lawsuits that would have placed blame upon the Club’s members.

In the years following this tragic event, many people blamed the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club for the tragedy, as they had originally bought and repaired the dam to turn the area into a holiday retreat in the mountains. However, they failed to properly maintain the dam, and as a result, heavy rainfall on the eve of the disaster meant that the structure was not strong enough to hold the excess water. Despite the evidence to suggest that they were very much to blame, they were never held legally responsible for the disaster. In keeping with the times, the courts viewed the dam's failure as an Act of God, and no legal compensation was paid to the survivors of the flood.

Individual members of the club did contribute substantially to the relief efforts. Along with about half of the club members, Henry Clay Frick donated thousands of dollars to the relief effort in Johnstown. After the flood, Andrew Carnegie, one of the club's better-known members, built the town a new library. In modern times, this former library is owned by the Johnstown Area Heritage Association, and houses the Flood Museum.

Aftermath

On February 5, 1904 the Cambria Freeman reported, under the headline "Will Pass Out of History":

The South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club, owners of the Conemaugh Reservoir at the time of the Great Flood, will soon pass out of history as an organization with the sale of all its personal effects remaining in the clubhouse at the reservoir site. Auctioneer George Harshberger has announced that the sale will take place on Thursday, the 25th inst., at the clubhouse, when the entire furnishings will be disposed of at auction.In the list to be disposed of are fifty bedroom suites, many yards of carpet, silverware and table ware with the club monogram engraved thereon and many odd pieces of furniture and bric-a-brac. At the time of the Great Flood the club house was handsomely furnished and was fully equipped to care for at least 200 guests. During the summer of 1889 the clubhouse remained open but has since been occupied only by a caretaker.

South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club Historic District

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club Historic District is a national historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.[1] The district includes eight contributing buildings remaining from the Club. The district includes the Club House and six cottages. They are representative of popular late-19th century architectural styles including Stick/Eastlake, Gothic Revival, and Queen Anne.[4]

See also

- In Sunlight, In a Beautiful Garden, a novel about the flood

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 Blogspot.com

- 1 2 "Johnstown Flood: People", National Park Service, 2010-04-13, retrieved 2010-05-20

- ↑ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Richard F. Truscello; Fred Denk & William Sisson (n.d.). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club Historic District" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-12-05.