Speech and language impairment

Speech and language impairment are basic categories that might be drawn in issues of communication involve hearing, speech, language, and fluency.

A speech impairment is characterized by difficulty in articulation of words. Examples include stuttering or problems producing particular sounds. Articulation refers to the sounds, syllables, and phonology produced by the individual. Voice, however, may refer to the characteristics of the sounds produced—specifically, the pitch, quality, and intensity of the sound. Often, fluency will also be considered a category under speech, encompassing the characteristics of rhythm, rate, and emphasis of the sound produced [1]

A language impairment is a specific impairment in understanding and sharing thoughts and ideas, i.e. a disorder that involves the processing of linguistic information. Problems that may be experienced can involve the form of language, including grammar, morphology, syntax; and the functional aspects of language, including semantics and pragmatics[1]

An individual can have one or both types of impairment. These impairments / disorders are identified by a speech and language pathologist.

Speech Disorders

The Following are brief definitions of several of the more prominent speech disorders:

Apraxia of speech

Apraxia of speech is the acquired form of motor speech disorder caused by brain injury, stroke or dementia.

Developmental verbal dyspraxia

Developmental verbal dyspraxia refers specifically to a motor speech disorder. This is a neurological disorder. Individuals suffering from developmental verbal apraxia encounter difficulty saying sounds, syllables, and words. The difficulties are not due to weakness of muscles, but rather on coordination between the brain and the specific parts of the body.[2][3] Apraxia of speech is the acquired form of this disorder caused by brain injury, stroke or dementia.

Interventions are more effective when they occur individually at first, and between three and five times per week. With improvements, children with apraxia may be transitioned into group therapy settings. Therapeutic exercises must focus on planning, sequencing, and coordinating the muscle movements involved in speech production. Children with developmental verbal dyspraxia must practice the strategies and techniques that they learn in order to improve. In addition to practice, feedback can be helpful to improve apraxia of speech. Tactile feedback (touch), visual feedback (watching self in mirror), and verbal feedback are all important additions.[4] Biofeedback has also been cited as a possible therapy. Functional training involves placing the individual in more speech situations, while providing him/her with a speech model, such as the SLP.[5] Because the cause is neurological, however, some patients do not progress. In these cases, AAC may be more appropriate.

Dysarthria

Dysarthria is a motor speech disorder that results from a neurological injury. Some stem from central damage, while other stem from peripheral nerve damage. Difficulties may be encountered in respiratory problems, vocal fold function, or velopharyngeal closure, for example.[5]

Orofacial myofunctional disorders

Orofacial myofunctional disorders refers to problems encountered when the tongue thrusts forward inappropriately during speech. While this is typical in infants, most children outgrow this. Children that continue to exaggerate the tongue movement may incorrectly produce speech sounds, such as /s/, /z/, “sh”, “ch”, and “j”. For example, the word, “some,” might be pronounced as “thumb”.[3]

The treatment of OMD will be based upon the professional’s evaluation.[6] Each child will present a unique oral posture that must be corrected. Thus, the individual interventions will vary. Some examples include:

- increasing awareness of muscles around the mouth

- increasing awareness of oral postures

- improving muscle strength and coordination

- improving speech sound productions

- improving swallowing patterns

Speech sound disorder

Speech sound disorders may be of two varieties: articulation (the production of sounds) or phonological processes (sound patterns). An articulation disorder may take the form of substitution, omission, addition, or distortion of normal speech sounds. Phonological process disorders may involve more systematic difficulties with the production of particular types of sounds, such as those made in the back of the mouth, like “k” and “g”.[3]

Naturally, abnormalities in speech mechanisms would need to be ruled out by a medical professional. Therapies for articulation problems must be individualized to fit the individual case. The placement approach—instructing the individual on the location in which the tongue should be and how to blow air correctly—could be helpful in difficulties with certain speech sounds. Another individual might benefit more from developing auditory discrimination skills, since he/she has not learned to identify error sounds in his/her speech. Generalization of these learned speech techniques will need to be generalized to everyday situations.[5] Phonological process treatment, on the other hand, can involve making syntactical errors, such as omissions in words. In cases such as these, explicit teaching of the linguistic rules may be sufficient.[7]

Some cases of speech sound disorders, for example, may involve difficulties articulating speech sounds. Educating a child on the appropriate ways to produce a speech sound and encouraging the child to practice this articulation over time may produce natural speech, Speech sound disorder. Likewise, stuttering does not have a single, known cause, but has been shown to be effectively reduced or eliminated by fluency shaping (based on behavioral principles) and stuttering modification techniques.

Stuttering

Stuttering is a disruption in the fluency of an individual’s speech, which begins in childhood and may persist over a lifetime. Stuttering is a form of disfluency; disfluency becomes a problem insofar as it impedes successful communication between two parties. Disfluencies may be due to unwanted repetitions of sounds, or extension of speech sounds, syllables, or words. Disfluencies also incorporate unintentional pauses in speech, in which the individual is unable to produce speech sounds.[3]

While the effectiveness is debated, most treatment programs for stuttering are behavioral. In such cases, the individual learns skills that improve oral communication abilities, such as controlling and monitoring the rate of speech. SLPs may also help these individuals to speak more slowly and to manage the physical tension involved in the communication process. Fluency may be developed by selecting a slow rate of speech, and making use of short phrases and sentences. With success, the speed may be increased until a natural rate of smooth speech is achieved.[8] Additionally, punishment for incorrect speech production should be eliminated, and a permissive speaking environment encouraged. Electronic fluency devices, which alter the auditory input and provide modified auditory feedback to the individual, have shown mixed results in research reviews.

Because stuttering is such a common phenomenon, and because it is not entirely understood, various opposing schools of thought emerge to describe its etiology. The Breakdown theories maintain that stuttering is the result of a weakening or breakdown in physical systems that are necessary for smooth speech production. Cerebral dominance theories (in the stutterer, no cerebral hemisphere takes the neurological lead) and theories of perseveration (neurological “skipping record” of sorts) are both Breakdown theories. Auditory Monitoring theories suggest that stutters hear themselves differently from how other people hear them. Since speakers adjust their communication based upon the auditory feedback they hear (their own speech), this creates conflict between the input and the output process. Psychoneurotic theories posit repressed needs as the source of stuttering. Lastly, Learning theories are straightforward—children learn to stutter. It should be clear that each etiological position would suggest a different intervention, leading to controversy with the field.[5]

Voice disorders

Voice disorders range from aphonia (loss of phonation) to dysphonia, which may be phonatory and/or resonance disorders. Phonatory characteristics could include breathiness, hoarseness, harshness, intermittency, pitch, etc. Resonance characteristics refer to overuse or underuse of the resonance chambers resulting in hypernasality or hyponasality.[5] Several examples of voice problems are vocal chord nodules or polyps, vocal chord paralysis, paradoxical vocal fold movement, and spasmodic dysphonia. Vocal chord nodules and polyps are different phenomena, but both may be caused by vocal abuse, and both may take the form of growths, bumps, or swelling on the vocal chords. Vocal fold paralysis is the inability to move one or both of the vocal chords, which results in difficulties with voice and perhaps swallowing. Paradoxical vocal fold movement occurs when the vocal chords close when they should actually be open. Spasmodic dysphonia is caused by strained vocal chord movement, which results in awkward voice problems, such as jerkiness or quavering.[3]

If nodules or polyps are present, and are large, surgery may be the appropriate choice for removal. Surgery is not recommended for children, however. Other medical treatment may suffice for slighter problems, such as those induced by gastroesophageal reflux disease, allergies, or thyroid problems. Outside of medical and surgical interventions, professional behavioral interventions can be useful in teaching good vocal habits and minimizing abuse of vocal cords. This voice therapy may instruct in attention to pitch, loudness, and breathing exercises. Additionally, the individual may be instructed on the optimal position to produce the maximum vocal quality. Bilateral paralysis is another disorder that may require medical or surgical interventions to return vocal cords to normalcy; unilateral paralysis may be treated medically or behaviorally.[9]

Paradoxical vocal fold movement (PVFM) is also treated medically and behaviorally. Behavioral interventions will focus on voice exercises, relaxation strategies, and techniques that can be used to support breath. More generally, however, PVFM interventions focus on helping an individual to understand what triggers the episode, and how to deal with it when it does occur.[9]

While there is no cure for spasmodic dysphonia, medical and psychological interventions can alleviate some of the symptoms. Medical interventions involve repeated injections of Botox into one or both of the vocal cords. This weakens the laryngeal muscles, and results in a smoother voice.[9]

Language Disorders

A language disorder is an impairment in the ability to understand and/or use words in context, both verbally and nonverbally. Some characteristics of language disorders include improper use of words and their meanings, inability to express ideas, inappropriate grammatical patterns, reduced vocabulary and inability to follow directions. One or a combination of these characteristics may occur in children who are affected by language learning disabilities or developmental language delay. Children may hear or see a word but not be able to understand its meaning. They may have trouble getting others to understand what they are trying to communicate.

Specific language impairment

Interventions for specific language impairment will be based upon the individual difficulties in which the impairment manifests. For example, if the child is incapable of separating individual morphemes, or units of sound, in speech, then the interventions may take the form of rhyming, or of tapping on each syllable. If comprehension is the trouble, the intervention may focus on developing metacognitive strategies to evaluate his/her knowledge while reading, and after reading is complete. It is important that whatever intervention is employed, it must be generalized to the general education classroom.[10]

Selective mutism

Selective mutism is a disorder that manifests as a child that does not speak in at least one social setting, despite being able to speak in other situations. Selective mutism is normally discovered when the child first starts school.[3]

Behavioral treatment plans can be effective in bringing about the desired communication across settings. Stimulus fading involves a gradual desensitization, in which the individual is placed in a comfortable situation and the environment is gradually modified to increase the stress levels without creating a large change in stress level. Shaping relies on behavioral modification techniques, in which successive attempts to produce speech is reinforced. Self-modeling techniques may also be helpful; for example, self-modeling video tapes, in which the child watches a video of him/herself performing the desired action, can be useful.

If additional confounding speech problems exist, a SLP may work with the student to identify what factors are complicating speech production and what factors might be increasing the mute behaviors. Additionally, he/she might work with the individual to become more comfortable with social situations, and with the qualities of their own voice. If voice training is required, they might offer this as well.[11]

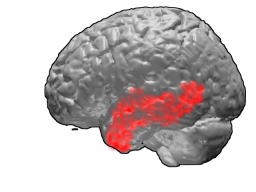

Aphasia

Aphasia refers to a family of language disorders that usually stem from injury, lesion, or atrophy to the left side of the brain that result in reception, perception, and recall of language; in addition, language formation and expressive capacities may be inhibited.[5]

Language-based learning disabilities

Language-based learning disabilities, which refer to difficulties with reading, spelling, and/or writing that are evidenced in a significant lag behind the individual’s same-age peers. Most children with these disabilities are at least of average intelligence, ruling out intellectual impairments as the causal factor.[3]

Diagnostic criteria

The DSM-5 and the ICD-10 are both used to make specific diagnostic decisions. Speech and language disorders commonly include communication issues, but also extend into various areas such as oral-motor function—sucking, swallowing, drinking, or eating. In some cases, a child's communication is delayed considerably behind his/her same-aged peers. The effects of these disorders can range from basic difficulties in the production of certain letter sounds to more comprehensive inabilities to generate (expressive) or understand (receptive) language. In most cases, the causal factors that create these speech and language difficulties are unknown. There are a wide variety of biological and environmental causal factors that can create them, ranging from drug abuse to neurological issues. For more information on causal hypotheses, refer to the section on models.[12]

Developmental disorders

Developmental disorders tend to have a genetic origin, such as mutations of FOXP2, which has been linked to Developmental verbal dyspraxia and Specific language impairment. Some of these impairments are caused by genetics. Interestingly, case histories often reveal a positive family history of communication disorders. Between 28% and 60% of children with a speech and language deficit have a sibling and/or parent who is also affected.[13] Down syndrome is another example of a genetic causal factor that may result in speech and/or language impairments. Stuttering is a disorder that is hypothesized to have a strong genetic component as well.

Some speech and language impairments have environmental causes. A specific language impairment, for example, may be caused by insufficient language stimulation in the environment. If a child does not have access to an adequate role model, or is not spoken to with much frequency, the child may not develop strong language skills. Furthermore, if a child has little stimulating experiences, or is not encouraged to develop speech, that child may have little incentive to speak at all and may not develop speech and language skills at an average pace.[14]

Developmental disabilities such as autism and neurological disorders such as cerebral palsy may also result in impaired communicative abilities. Similarly, malformation or malfunctioning of the respiratory system or speech mechanisms may result in speech impairments. For example, a cleft palate will allow too much air to pass through the nasal cavity and a cleft lip will not allow the individual to correctly form sounds that require the upper lip.[14] The development of vocal fold nodules represents another issue of biological causation. In some cases of biological origin, medical interventions such as surgery or medication may be required. Other cases may require speech therapy or behavioral training.

Acquired disorders

Acquired disorders result from brain injury, stroke or atrophy, many of these issues are included under the Aphasia umbrella. Brain damage, for example, may result in various forms of aphasia if critical areas of the brain such as Broca’s or Wernicke's area are damaged by lesions or atrophy as part of a dementia

Speech and language assessment

What follows are a list of frequently used measures of speech and language skills, and the age-ranges for which they are appropriate.[1]

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – Preschool (3–6 years)

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (6–21 years)

- MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories (0–12 months)

- The Rossetti Infant-Toddler Language Scale (0–36 months)

- Preschool Language Scale (0–6 years)

- Expressive One-word Picture Vocabulary Test (2–15 years)

- Bankson-Bernthal Phonological Process Survey Test (2–16 years)

- Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation 2 (2–21 years)

- Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (2.5–40 years)

In the United States of America

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) 2004, the federal government has defined a speech or language impairment as "a communication disorder such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, or a voice impairment, which adversely affects a child's learning." In order to qualify in the educational system as having a speech or language impairment, the child's speech must be either unintelligible much of the time or he/she must have been professionally diagnosed as having either a speech impairment or language delay which requires intervention. Additionally, IDEA 2004 contains an exclusionary clause that stipulates that a speech or language impairment may not be either cultural, ethnic, bilingual, or dialectical differences in language, temporary disorders (such as those induced by dental problems), or delayed abilities in producing the most difficult linguistic sounds in a child's age range.[14]

Management

Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) offer many services to children with speech or language disabilities.

Speech-Language Pathology

Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) may provide individual therapy for the child to assist with speech production problems such as stuttering. They may consult with the child's teacher about ways in which the child might be accommodated in the classroom, or modifications that might be made in instruction or environment. The SLP can also make crucial connections with the family, and help them to establish goals and techniques to be used in the home. Other service providers, such as counselors or vocational instructors may also be included in the development of goals as the child transitions into adulthood.[12]

The individual services that the child receives will depend upon the needs of that child. Simpler problems of speech, such as hoarseness or vocal fatigue (voicing problems) may be solved with basic instruction on how to modulate one's voice. Articulation problems could be remediated by simple practice in sound pronunciation. Fluency problems may be remediated with coaching and practice under the guidance of trained professionals, and may disappear with age. However, more complicated problems, such as those accompanying autism or strokes, may require many years of one-on-one therapy with a variety of service providers. In most cases, it is imperative that the families be included in the treatment plans since they can help to implement the treatment plans. The educators are also a critical link in the implementation of the child's treatment plan.[15]

For children with language disorders, professionals often relate the treatment plans to classroom content, such as classroom textbooks or presentation assignments. The professional teaches various strategies to the child, and the child works to apply them effectively in the classroom. For success in the educational environment, it is imperative that the SLP or other speech-language professional have a strong, positive rapport with the teacher(s).[10]

Speech-language pathologists create plans that cater to the individual needs of the patient. If speech is not practical for a patient, the SLP will work with the patient to decide upon an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) method or device to facilitate communication. They may work with other patients to help them make sounds, improve voices, or teach general communication strategies. They also work with individuals who have difficulties swallowing. In addition to offering these types of communication training services, SLPs also keep records of evaluation, progress, and eventual discharge of patients, and work with families to overcome and cope with communication impairments (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009).

In many cases, SLPs provide direct clinical services to individuals with communication or swallowing disorders. SLPs work with physicians, psychologists, and social workers to provide services in the medical domain, and collaborate with educational professionals to offer additional services for students to facilitate the educational process. Thus, speech-language services may be found in schools, hospitals, outpatient clinics, and nursing homes, among other settings.[16]

The setting in which therapy is provided to the individual depends upon the age, type, and severity of the individual's impairment. An infant/toddler may engage in an early intervention program, in which services are delivered in a naturalistic environment in which the child is most comfortable—probably his/her home. If the child is school-aged, he/she may receive speech-language services at an outpatient clinic, or even at his/her home school as part of a weekly program. The type of setting in which therapy is offered depends largely upon characteristics of the individual and his/her disability.

As with any professional practice that is informed by ongoing research, controversies exist in the fields that deal with speech and language disorders. One such current debate relates to the efficacy of oral motor exercises and the expectations surrounding them. According to Lof,[17] non-speech oral motor exercises (NS-OME) includes “any technique that does not require the child to produce a speech sound but is used to influence the development of speaking abilities.” These sorts of exercises would include blowing, tongue push-ups, pucker-smile, tongue wags, big smile, tongue-to-nose-to-chin, cheek puffing, blowing kisses, and tongue curling, among others. Lof continues, indicating that 85% of SLPs are currently using NS-OME. Additionally, these exercises are used for dysarthria, apraxia, late talkers, structural anomalies, phonological impairments, hearing impairments, and other disorders. Practitioners assume that these exercises will strengthen articulatory structures and generalize to speech acts. Lof reviews 10 studies, and concludes that only one of the studies shows benefits to these exercises (it also suffered serious methodological flaws). Lof ultimately concludes that the exercises employ the same structures, but are used for different functions.[18] The NS-OME position is not without its supporters, however, and the proponents are numerous.

Interventions

Intervention services will be guided by the strengths and needs determined by the speech and language evaluation. The areas of need may be addressed individually until each one is functional; alternatively, multiple needs may be addressed simultaneously through the intervention techniques. If possible, all interventions will be geared towards the goal of developing typical communicative interaction. To this end, interventions typically follow either a preventive, remedial, or compensatory model. The preventive service model is common as an early intervention technique, especially for children whose other disorders place them at a higher risk for developing later communication problems. This model works to lessen the probability or severity of the issues that could later emerge. The remedial model is used when an individual already has a speech or language impairment that he/she wishes to have corrected. Compensatory models would be used if a professional determines that it is best for the child to bypass the communication limitation; often, this relies on AAC.

Language intervention activities are used in some therapy sessions. In these exercises, an SLP or other trained professional will interact with a child by working with the child through play and other forms of interaction to talk to the child and model language use. The professional will make use of various stimuli, such as books, objects, or simple pictures to stimulate the emerging language. In these activities, the professional will model correct pronunciation, and will encourage the child to practice these skills. Articulation therapy may be used during play therapy as well, but involves modeling specific aspects of language—the production of sound. The specific sounds will be modeled for the child by the professional (often the SLP), and the specific processes involved in creating those sounds will be taught as well. For example, the professional might instruct the child in the placement of the tongue or lips in order to produce certain consonant sounds.[19]

Technology is another avenue of intervention, and can help children whose physical conditions make communication difficult. The use of electronic communication systems allow nonspeaking people and people with severe physical disabilities to engage in the give and take of shared thought.

Adaptability and limitations

While some speech problems, such as certain voice problems, require medical interventions, many speech problems can be alleviated through effective behavioral interventions and practice. In these cases, instruction in speech techniques or speaking strategies, coupled with regular practice, can help the individual to overcome his/her speaking difficulties. In other, more severe cases, the individual with speech problems may compensate with AAC devices.[14]

Speech impairments can seriously limit the manner in which an individual interacts with others in work, school, social, and even home environments. Inability to correctly form speech sounds might create stress, embarrassment, and frustration in both the speaker and the listener. Over time, this could create aggressive responses on the part of the listener for being misunderstood, or out of embarrassment. Alternatively, it could generate an avoidance of social situations that create these stressful situations. Language impairments create similar difficulties in communicating with others, but may also include difficulties in understanding what others are trying to say (receptive language). Because of the pervasive nature of language impairments, communicating, reading, writing, and academic success may all be compromised in these students. Similar to individuals with speech impairments, individuals with language impairments may encounter long-term difficulties associated with work, school, social, and home environments.[14]

Assistive technology

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) includes all forms of communication other than oral communication that an individual might employ to make known his/her thoughts. AAC work to compensate for impairments that an individual might have with expressive language abilities. Each system works to maintain a natural and functional level of communication. There is no one best type of AAC for all individuals; rather, the best type of AAC will be determined by the strengths and weaknesses of a specific individual. While there are a large amount of types of AAC, there are fundamentally two categories: aided and unaided.

Unaided systems of communication are those that require both communication parties to be physically present in the same location. Examples of unaided systems include gestures, body language, sign language, and communication boards. Communication boards are devices upon which letters, words, or pictorial symbols might be displayed; the individual may interface with the communication board to express him/herself to the other individual.

Aided systems of communication do not require both individuals to be physically present in the same location, though they might be. Aided systems are often electronic devices, and they may or may not provide some form of voice output. If a device does create a voice output, it is referred to as a speech generating device. While the message may take the form of speech output, it may also be printed as a visual display of speech. Many of these devices can be connected to a computer, and in some cases, they may even be adapted to produce a variety of different languages.[14][20]

Inclusion vs. exclusion

Students identified with a speech and language disability often qualify for an Individualized Education Plan as well as particular services. These include one-on-one services with a speech and language pathologist. Examples used in a session include reading vocabulary words, identifying particular vowel sounds and then changing the context, noting the difference. School districts in the United States often have speech and language pathologists within a special education staff to work with students. Additionally, school districts can place students with speech and language disabilities in a resource room for individualized instruction. A combination of early intervention and individualized support has shown promise increasing long-term academic achievement with students with this disability.[21]

Students might work individually with a specialist, or with a specialist in a group setting. In some cases, the services provided to these individuals may even be provided in the regular education classroom. Regardless of where these services are provided, most of these students spend small amounts of time in therapy and the large majority of their time in the regular education classroom with their typically developing peers.[22]

Therapy often occurs in small groups of three or four students with similar needs. Meeting either in the office of the speech-language pathologist or in the classroom, sessions may take from 30 minutes to one hour. They may occur several times per week. After introductory conversations, the session is focused on a particular therapeutic activity, such as coordination and strengthening exercises of speech muscles or improving fluency through breathing techniques. These activities may take the form of games, songs, skits, and other activities that deliver the needed therapy. Aids, such as mirrors, tape recorders, and tongue depressors may be utilized to help the children to become aware of their speech sounds and to work toward more natural speech production.

Prevalence

In 2006, the U.S. Department of Education indicated that more than 1.4 million students were served in the public schools’ special education programs under the speech or language impairment category of IDEA 2004.[14] This estimate does not include children who have speech/language problems secondary to other conditions such as deafness; this means that if all cases of speech or language impairments were included in the estimates, this category of impairment would be the largest. Another source has estimated that communication disorders—a larger category, which also includes hearing disorders—affect one of every 10 people in the United States.[12]

ASHA has cited that 24.1% of children in school in the fall of 2003 received services for speech or language disorders—this amounts to a total of 1,460,583 children between 3 –21 years of age.[13] Again, this estimate does not include children who have speech/language problems secondary to other conditions. Additional ASHA prevalence figures have suggested the following:

- Stuttering affects approximately 4% to 5% of children between the ages of 2 and 4.

- ASHA has indicated that in 2006:

- Almost 69% of SLPs served individuals with fluency problems.

- Almost 29% of SLPs served individuals with voice or resonance disorders.

- Approximately 61% of speech-language pathologists in schools indicated that they served individuals with SLI

- Almost 91% of SLPs in schools indicated that they servedindividuals with phonological/articulation disorder

- Estimates for language difficulty in preschool children range from 2% to 19%.

- Specific Language Impairment (SLI) is extremely common in children, and affects about 7% of the childhood population.[13]

Discrimination

While more common in childhood, speech impairments can result in a child being bullied. Bullying is a harmful activity that often takes place at school, though may be present in adult life. Bullying involves the consistent and intentional harassment of another individual, and may be physical or verbal in nature.[23]

Speech impairments (e.g., stuttering) and language impairments (e.g., dyslexia, auditory processing disorder) may also result in discrimination in the workplace. For example, an employer would be discriminatory if he/she chose to not make reasonable accommodations for the affected individual, such as allowing the individual to miss work for medical appointments or not making onsite-accommodations needed because of the speech impairment. In addition to making such appropriate accommodations, the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) protects against discrimination in “job application procedures, hiring, advancement, discharge, compensation, job training, and other terms, conditions, and privileges of employment”.[24]

Terminology

Smith [14] offers the following definitions of major terms that are important in the world of speech and language disorders.

- Alternative and augmentative communication (AAC): Assistive technology that helps individuals to communicate; may be low-tech or high-tech

- Articulation disorder: Atypical generation of speech sounds

- Cleft lip: Upper lip is not connected, resulting in abnormal speech

- Cleft palate: An opening in the roof of the mouth that allows too much air to pass through nasal cavity, resulting in abnormal speech

- Communication: Transfer of knowledge, ideas, opinions, and feelings

- Communication board: Low-tech AAC device that displays pictures or words to which an individual points to communicate

- Communication disorder: Disorders in speech, language, hearing, or listening that create difficulties in effective communication

- Disfluency: Interruptions in the flow of an individual’s speech

- Expressive language: Ability to express one’s thoughts, feelings, or information

- Language: Rule-based method used for communication

- Language delays: Slowed development of language skills

- Language disorder: Difficulty/inability to comprehend/make use of the various rules of language

- Loudness: A characteristic of voice; refers to intensity of sound

- Morphology: Rules that determine structure and form of words

- Otitis media: Middle ear infection that can interrupt normal language development

- Pitch: A characteristic of voice; usually either high or low

- Phonological awareness: Understanding, identifying, and applying the relationships between sound and symbol

- Phonology: Rules of a language that determine how speech sounds work together to create words and sentences

- Pragmatics: Appropriate use of language in context

- Receptive language: Ability to comprehend information that is received

- Semantics: System of language that determines content, intent, and meaning of language

- Speech: Vocal production of language

- Speech impairment: Abnormal speech is unintelligible, unpleasant, or creates an ineffective communication process

- Speech/language pathologist: Professionals who help individuals to maximize their communication skills.

- Speech synthesizer: Assistive technology that creates voice

- Stuttering: Hesitation or repetition contributes to dysfluent speech

- Syntax: Rules that determine word endings and word orders

- Voice problem: Abnormal oral speech, often including atypical pitch, loudness, or quality

History

In the mid 19th century, the scientific endeavors of such individuals as Charles Darwin gave rise to more systematic and scientific consideration of physical phenomenon, and the work of others, such as Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke, also lent scientific rigor to the study of speech and language disorders. The late 19th century saw an increase in “pre-professionals,” those who offered speech and language services based upon personal experiences or insights. Several trends were exhibited even in the 19th century, some have indicated the importance of elocution training in the early 19th century, through which individuals would seek out those with training to improve their vocal qualities. By 1925 in the USA interest in these trends lead to the forming of the organization that would become American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) and the birth of speech-language pathology.[25]

The twentieth century has been proposed to be composed of four major periods: Formative Years, Processing Period, Linguistic Era, and Pragmatics Revolution. The Formative Years, which began around 1900 and ended around WWII, was a time during which the scientific rigor extended and professionalism entered the picture. During this period, the first school-based program began in the U.S. (1910). The Processing Period, from roughly 1945-1965, further developed the assessment and interventions available for general communication disorders; much of these focused on the internal, psychological transactions involved in the communication process. During the Linguistic Era, from about 1965-1975, professionals began to separate language deficits from speech deficits, which had major implications for diagnosis and treatment of these communication disorders. Lastly, the Pragmatics Revolution has continued to shape the professional practice by considering major ecological factors, such as culture, in relation to speech and language impairments. It was during this period that IDEA was passed, and this allowed professionals to begin working with a greater scope and to increase the diversity of problems with which they concerned themselves.[14] [25]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Batshaw, Mark L (2002). Children with disabilities. 5. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. ISBN 0-86433-137-1. OCLC 608999305.

- ↑ Souza TN, Payão Mda C, Costa RC (2009). "Childhood speech apraxia in focus: theoretical perspectives and present tendencies". Pro Fono. 21 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1590/S0104-56872009000100013. PMID 19360263.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Child Speech and Language". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ↑ ASHA. (2009). Childhood apraxia of speech. Retrieved July 12, 2009, from http://asha.org/public/speech/disorders/ChildhoodApraxia.htm.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Palmer, John; Yantis, Phillip A. (1990). Survey of communication disorders. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-06743-5. OCLC 20168213.

- ↑ ASHA. (2009). Orofacial myofunctional disorders. Retrieved July 10, 2009, from http://asha.org/public/speech/disorders/OMD.htm

- ↑ ASHA. (2009). Speech sound disorders: Articulation and phonological processes. Retrieved July 9, 2009, from http://asha.org/public/speech/disorders/SpeechSoundDisorders.htm.

- ↑ ASHA. (2009). Stuttering. Retrieved July 19, 2009, from http://asha.org/public/speech/disorders/stuttering.htm.

- 1 2 3 ASHA (2009). Voice disorders. Retrieved July 16, 2009, from http://asha.org/public/speech/disorders/voice.htm.

- 1 2 ASHA. (2009). Language-based learning disabilities. Retrieved July 10, 2009, from http://asha.org/public/speech/disorders/LBLD.htm

- ↑ ASHA. (2009 k). Selective mutism. Retrieved July 21, 2009, from http://asha.org/public/speech/disorders/SelectiveMutism.htm

- 1 2 3 "Speech and Language Impairments". National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities (NICHCY). Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- 1 2 3 ASHA. (2009). Incidence and prevalence of speech, voice, and language disorders in the adults in the United States: 2008 edition. Retrieved July 7, 2009, from http://asha.org/research/reports/speech_voice_language.htm.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Smith, Deborah D.; Tyler, Naomi Chodhuri (2009). Introduction to Special Education: Making A Difference (7th Edition). Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-205-60056-5. OCLC 268789042.

- ↑ Morales, S. (2009). The mechanics of speech and language. Retrieved July 10, 2009, from http://www.childspeech.net/u_ii.html.

- ↑ Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2009). Speech-language pathologist. Retrieved July 10, 2009, from http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos099.htm.

- ↑ Lof, G.L. (2006). Logic, theory, and evidence against the use of non-speech oral motor exercises to change speech sound production. ASHA Convention 2006, 1-11.

- ↑ Lof, G.L. (2003). Oral motor exercises and treatment outcomes. Language Learning and Education, April 2003, 7-11.

- ↑ Kids Health. (2009). Speech language therapy. Retrieved July 13, 2009, from http://kidshealth.org/parent/system/ill/speech_therapy.html#.

- ↑ ASHA. (2009 l). Augmentative and alternative communication. Retrieved July 11, 2009, from http://asha.org/public/speech/disorders/AAC.htm.

- ↑ Reynolds, Arthur J.; Judy A. Temple; Dylan L. Robertson; Emily A. Mann (2001). "Long-term Effects of an Early Childhood Intervention on Educational Achievement and Juvenile Arrest". Journal of the American Medical Association. 285 (18): 2339–2346. doi:10.1001/jama.285.18.2339. PMID 11343481.

- ↑ Mastropieri, Margo A.; Scruggs, Thomas E. (2009). The Inclusive Classroom: Strategies for Effective Instruction (4th Edition). Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-500170-6. OCLC 268789048.

- ↑ IStutter. (2005). Teasing and bullying: Facts and support. Retrieved July 22, 2009, from http://www.latrobe.edu.au/istutter/?q=node/16.

- ↑ Parry, W.D. (2009). Being your own best advocate. Retrieved July 26, 2009, from http://www.valsalva.org/advocate.htm.

- 1 2 Duchan, J.F. (2008). Getting here: A short history of speech pathology in America. Retrieved July 15, 2009, from http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~duchan/new_history/overview.html.

Further reading

- American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology - Articles in Press

- Journal of Communication Disorders - Articles in Press

- DeThorne, Laura S.; Cynthia J. Johnson; Louise Walder; Jamie Mahurin-Smith (May 2009). "When "Simon Says" Doesn't Work: Alternatives to Imitation for Facilitating Early Speech Development". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 18 (2): 133–145. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2008/07-0090). PMID 18930909. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- Maas, Edwin; Donald A. Robin; Shannon N. Austermann Hula; Skott E. Freedman; Gabriele Wulf; Kirrie J. Ballard; Richard A. Schmidt (August 2008). "Principles of Motor Learning in Treatment of Motor Speech Disorders". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 17 (3): 277–298. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2008/025). PMID 18663111. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- DeBonis, David A.; Deborah Moncrieff (February 2008). "Auditory Processing Disorders: An Update for Speech-Language Pathologists". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 17 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2008/002). PMID 18230810. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- "Discussion Meeting Issue 'Language in developmental and acquired disorders: converging evidence for models of language representation in the brain' - Table of Contents". Royal Society Publishing. 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- Schlosser, Ralf W.; Oliver Wendt (August 2008). "Effects of Augmentative and Alternative Communication Intervention on Speech Production in Children With Autism: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 17 (3): 212–230. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2008/021). PMID 18663107. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- Clark, Heather M. (November 2003). "Neuromuscular Treatments for Speech and Swallowing". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 12 (4): 400–415. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2003/086). PMID 14658992. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Speech and language impairment. |

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association

- American Academy of Audiology

- Auditory Processing Disorder in the UK (APDUK)

- Canadian Association of Speech-Language Pathologists & Audiologists

- Controversial Practices in Children's Speech Sound Disorders - Oral Motor Exercises, Dietary Supplements, Auditory Integration Training

- Apraxia-Kids Glossary of Common Acronyms and Abbreviations

- National Aphasia Association

- National Association of Special Education Teachers: Speech and Language Impairment

- National Center for Voice and Speech

- Speech and Language Development

- Speech & Language Milestone Chart

- Talking Point

- Voice Matters