Standing Rock Indian Reservation

| Standing Rock Indian Reservation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indian reservation | ||

|

Standing Rock Native American Reservation straddles the border between North and South Dakota | ||

| ||

| Coordinates: 45°45′0″N 101°12′0″W / 45.75000°N 101.20000°WCoordinates: 45°45′0″N 101°12′0″W / 45.75000°N 101.20000°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State |

North Dakota South Dakota | |

| North Dakota Counties |

Sioux County Ziebach County | |

| South Dakota Counties |

Corson County Dewey County | |

| Area | ||

| • Land | 3,571.9 sq mi (9,251.2 km2) | |

| Population (2010)[1] | ||

| • Total | 8,217 | |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CST (UTC-4) | |

| ZIP code | 58538 | |

| Area code(s) | 701 | |

| Website |

standingrock | |

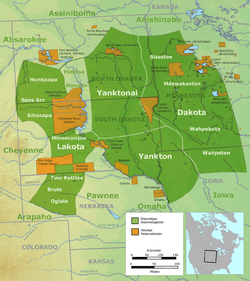

The Standing Rock Indian Reservation is a Hunkpapa Lakota, Sihasapa Lakota and Yanktonai Dakota Native American reservation in North Dakota and South Dakota in the United States. The sixth-largest reservation in land area in the United States, Standing Rock includes all of Sioux County, North Dakota, and all of Corson County, South Dakota, plus slivers of northern Dewey and Ziebach Counties in South Dakota, along their northern county lines at Highway 20.

The reservation has a land area of 9,251.2 square kilometers (3,571.9 sq mi) and a population of 8,250 as of the 2000 census.[2] The largest communities on the reservation are Fort Yates, Cannon Ball and McLaughlin. Other communities within the reservation include: Wakpala, Little Eagle, Bullhead, Porcupine, Kenel, McIntosh, Morristown, Selfridge, Solen.

History

Together with the Hunkpapa and Blackfoot bands, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is part of the Great Sioux Nation. In 1868 the lands of the Great Sioux Nation were reduced in the Fort Laramie Treaty to the east side of the Missouri River and the state line of South Dakota in the west. The Black Hills, considered by the Sioux to be sacred land, are located in the center of territory awarded to the tribe. In direct violation of the treaty, in 1874 General George A. Custer and his 7th Cavalry entered the Black Hills and discovered gold, starting a gold rush. The United States Government wanted to buy or rent the Black Hills from the Lakota people, but the Great Sioux Nation, led by their spiritual leader Sitting Bull, refused to sell or rent their lands. The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations which occurred between 1876 and 1877 between the Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne and the government of the United States. Among the many battles and skirmishes of the war was the Battle of the Little Bighorn, often known as Custer's Last Stand, the most storied of the many encounters between the U.S. army and mounted Plains Native Americans. That Native American victory notwithstanding, the U.S. with its superior resources was soon able to force the Native Americans to surrender, primarily by attacking and destroying their encampments and property. The Agreement of 1877 (19 Stat. 254, enacted February 28, 1877) officially annexed Sioux land and permanently established Native American reservations. The Agreement of 1877 allotted Native American lands into 160 acre lots to individuals to divide the nation and the U.S. government took the Black Hills from the Sioux Nation.[3]

In February 1890, the United States government broke a Lakota treaty by adjusting the Great Sioux Reservation, an area that formerly encompassed the majority of the state, and breaking it up into five smaller reservations.[4] The government was accommodating white homesteaders from the eastern United States; in addition, it intended to "break up tribal relationships" and "conform Indians to the white man's ways, peaceably if they will, or forcibly if they must".[5] On the reduced reservations, the government allocated family units on 320-acre (1.3 km2) plots for individual households. Although the Lakota were historically a nomadic people living in tipis and their Plains Native American culture was based strongly upon buffalo and horse culture, they were expected to farm and raise livestock. With the goal of assimilation, they were forced to send their children to boarding schools; the schools taught English and Christianity, as well as American cultural practices. Generally, they forbade inclusion of Native American traditional culture and language. They were beaten if they tried to do anything related to their native culture.

The farming plan failed to take into account the difficulty that Lakota farmers would have in trying to cultivate crops in the semi-arid region of South Dakota. By the end of the 1890 growing season, a time of intense heat and low rainfall, it was clear that the land was unable to produce substantial agricultural yields and, with the bison having been virtually eradicated a few years earlier, the Lakota were at risk of starvation. The people turned to the Ghost Dance ritual, which frightened the supervising agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Agent James McLaughlin asked for more troops. He claimed that spiritual leader Sitting Bull was the real leader of the movement. A former agent, Valentine McGillycuddy, saw nothing extraordinary in the dances and ridiculed the panic that seemed to have overcome the agencies, saying: "The coming of the troops has frightened the Indians. If the Seventh-Day Adventists prepare the ascension robes for the Second Coming of the Savior, the United States Army is not put in motion to prevent them. Why should not the Indians have the same privilege? If the troops remain, trouble is sure to come."[6]

Nonetheless, thousands of additional U.S. Army troops were deployed to the reservation. On December 15, 1890, Sitting Bull was arrested for failing to stop his people from practicing the Ghost Dance.[7] During the incident, one of Sitting Bull's men, Catch the Bear, fired at Lieutenant "Bull Head", striking his right side. He instantly wheeled and shot Sitting Bull, hitting him in the left side, and both men subsequently died.[8]

The Hunkpapa who lived in Sitting Bull's camp and relatives fled to the south. They joined the Big Foot Band in Cherry Creek, South Dakota then traveled to the Pine Ridge Reservation to meet with Chief Red Cloud. The 7th Cavalry caught them at a place called Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890. The 7th Cavalry, whilst attempting to disarm the Lakota people, killed 300 people including women and children at Wounded Knee.[3]

Governance and districts

.jpg)

According to its constitution,[9] Standing Rock's governing body is the elected 17-member Tribal Council, including the Tribal Chairman, Vice Chairman, Secretary, and 14 representatives: six at-large and eight from its regional districts:

- Fort Yates (Long Soldier)

- Porcupine

- Kenel

- Wakpala

- Running Antelope (Little Eagle)

- Bear Soldier (McLaughlin)

- Rock Creek (Bullhead)

- Cannonball

In 2014, President Barack Obama accompanied by Michelle Obama made his first visit to a Native American reservation during the annual Cannon Ball Flag Day Celebration.[10] It was one of the few visits by a sitting American President to a Native American reservation.[11] His visit was met with mixed feelings by the reservation, with concerns that specifics on treaty issues and government appropriations were not addressed.[12]

Flooding

In the 1960s, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation built five large dams on the Missouri River, and implemented the Pick–Sloan Missouri Basin Program, forcing Native Americans to relocate from flooded areas. Over 200,000 acres on the Standing Rock Reservation and the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota were flooded by the Oahe Dam alone. As of 2015, poverty remains a problem for the displaced populations in the Dakotas, who are still seeking compensation for the loss of the towns submerged under Lake Oahe, and the loss of their traditional ways of life.[13]

Mascot issue with University of North Dakota

The athletic teams of the University of North Dakota (UND) were known as the Fighting Sioux. Controversy surrounding the use of Native American mascots prompted the NCAA to ban the use of "hostile and abusive" Native American mascots in August 2005.[14] An exception was made to allow the use of tribal names if they are approved by that tribe.[15] Since the Tribal Council of the Standing Rock Sioux has not approved UND's use of "Fighting Sioux",[16][17] the ban applied to UND. After years with no mascot, UND became the Fighting Hawks in 2015.

Dakota Access Pipeline

On April 1, 2016, an elder member of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and her grandchildren established the Sacred Stone Camp to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline, which they claim threatens the only water supply for the Standing Rock Reservation. Founded by LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, the camp is on her private land, and is a center for cultural preservation and spiritual resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline.[18][19][20][21] Protests at the pipeline site in North Dakota began in the spring of 2016 and drew indigenous people from throughout North America as well as many other supporters, creating the largest gathering of Native Tribes in the past 100 years.[22] A number of planned arrests occurred when people locked themselves to heavy machinery in civil disobedience.[23] Criticism has been directed at Facebook for assisting the local authorities in censoring the protesters.[24]

In the summer of 2016, a group of young activists from Standing Rock ran from North Dakota to Washington, D.C., to present a petition in protest of the construction of Energy Transfer Partners' Dakota Access Pipeline, which is part of the Bakken pipeline, and have launched an international campaign called ReZpect our Water.[25] The pipeline, which goes from North Dakota to Illinois, the activists argue, would jeopardize the water source of the reservation, the Missouri River.[26][27] The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has filed an injunction against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to stop building the pipeline.[28][29] In April 2016, three federal agencies -- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Department of Interior, and Advisory Council on Historic Preservation—requested a full Environmental Impact Statement of the pipeline.[30] In August 2016, protests were held near Cannon Ball, North Dakota.[31]

By late September, it was reported that there were over 300 federally recognized Native American tribes and an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 pipeline resistance supporters residing in the camp, with several thousand more on weekends.[32]

Protests at the pipeline site have continued and have drawn indigenous people from throughout North America, as well as other supporters. A number of planned arrests occurred when people locked themselves to heavy machinery.[23] On September 3, 2016, the Dakota Access Pipeline brought in a private security firm. The company used bulldozers to dig up part of the pipeline route that was subject to a pending injunction motion; it contained possible Native graves and burial artifacts. The bulldozers arrived within a day from when the tribe filed legal action.[33] When unarmed protesters moved near the bulldozers, the guards used pepper spray and guard dogs to protect the site they were told to guard. At least six protesters were treated for dog bites, and an estimated 30 protesters were pepper-sprayed before the security guards and their dogs exited the scene in trucks.[34]

The pipeline construction company claimed they hired the security company because the protests have not been peaceful.[35] The Morton County Sheriff, Kyle Kirchmeier, described the September 3, 2016 protest, saying protesters crossed onto private property and attacked security guards with "wooden posts and flag poles." He said, "Any suggestion that today's event was a peaceful protest, is false." The sheriff told reporters that he had heard rumors of pipe bombs, but according to Bill McKibben, founder of a group connected to the protests, "it turned out he’d heard rumors about ceremonial peace pipes".[36]

Shortly thereafter, on September 7, 2016,[37] President Barack Obama was confronted at a televised town hall meeting with Laotian University Students, and right after the court battle to stop the pipeline went against the tribe, three government agencies suddenly intervened. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the United States Department of the Interior (DOI) and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation gave the order to halt the construction of the pipeline until further environmental assessments have taken place.[38] There is no evidence of what role President Obama himself may or may not have played in this decision.

Dakota Access agreed to temporarily halt construction in parts of North Dakota, until September 9, to help "keep the peace."[39] When a federal judge denied the injunction sought by the tribe on the 9th, the Department of the Interior, Department of Justice, and the Department of the Army (which oversees the Corps of Engineers) stepped in, halting construction of the pipeline around Lake Oahe,[40] 20 miles (32 km) either side of the Lake, but not halting the project altogether.[41]

A Colonial Pipeline Leak, believed to have begun sometime on September 12, 2016 in Alabama, spilled an estimated amount of 350,000 gallons (1,325 m³) of gasoline, further fueling the criticism of the Dakota Access Pipeline from The Standing Rock Tribe.[42]

On the weekend of December 2, 2016 approximately 2000 United States military veterans arrived in North Dakota in support of the activists in an action dubbed The Veterans Stand for Standing Rock. The veterans pledged to form a human shield to protect the protestors from police.[43]

Media attention and public awareness

As of late September 2016, major U.S. broadcast news outlets have given scant attention to the Standing Rock protests, even after a video was aired on Democracy Now! showing Dakota Access guard dogs with bloody mouths after attacking protesters.[21] Democracy Now! journalist Amy Goodman filmed the incident, which she published in support of the Native American opposition to the pipeline.[44] Following the publishing of her video, North Dakota Police issued an arrest warrant under accusations of Criminal Trespass. Goodman responded "This is an unacceptable violation of freedom of the press..."[45]

The 2016 Democratic and Republican presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump[46] made no comments during the campaign regarding the Dakota Access Pipeline. 2016 Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein protested at the site, including spray painting equipment, that resulted in charges of criminal trespass and criminal mischief for both her and her running mate Ajamu Baraka.[47] 2016 Democratic presidential primary candidate and Vermont US Senator Bernie Sanders has been critical of the Dakota Access Pipeline.[48]

Susan Sarandon, Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert Redford, and Katy Perry have all publicly expressed their support for the Standing Rock demonstrations of pipeline resistance, with some even traveling to join in person.

On September 23, 2016, two days after Standing Rock Chairman Dave Archambault II addressed the United Nations, Standing Rock received news that the property being occupied to stage their protests had been purchased by the Energy Transfer Partners, from David and Brenda Meyer of Flasher, ND, in an assumed attempt to deter further protests that may continue to hinder the construction of the pipeline.[49] The Sioux Nation claims that David and Brenda Meyer permitted their land to be used for staging.

Project halted

On December 4, a day before the deadline for a protester camp evacuation, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers announced that it would not permit an easement through federal land but would temporarily halt the construction of the pipeline to allow an environmental impact review. Alternate routes for the pipeline shall be explored.[50][51]

Notable tribal members

- Vine Deloria, Jr. (1933–2005), activist and essayist

- Tiffany Midge, poet

- Susan Power (b. 1961), novelist

- Wayne Trottier, North Dakota state legislator

- David Archambault II, Tribal Chair, 2013–present[52][53]

See also

- Dakota Access Pipeline protests

- Prairie Knights Casino and Resort, a tribe operated casino on the Standing Rock Indian reservation, near Fort Yates, North Dakota.

References

- ↑ http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

- ↑ "Standing Rock Reservation, South Dakota/North Dakota". Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- 1 2 "ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE". Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ Kehoe, The Ghost Dance, p. 15.

- ↑ Wallace, Anthony F. C. "Revitalization Movements: Some Theoretical Considerations for Their Comparative Study", American Anthropologist n.s. 58(2):264-81. 1956

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2002). The Reckless Decade: America in the 1890s. University of Chicago Press. p. 18.

- ↑ Kehoe, The Ghost Dance, p. 20.

- ↑ "Sitting Bull: Biography". Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-05-15.

- ↑ "Standing Rock Constitution, approved 1958, with amendments through 2008" (PDF). Standing Rock Tribe. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- ↑ Zezima, Katie (13 June 2014). "As Obama makes rare presidential visit to Indian reservation, past U.S. betrayals loom" (Includes video of President's address). The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Thiele, Raina (20 June 2014). "The President and First Lady's Historic Visit to Indian Country". WhiteHouse.gov. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Montagne, Renee; Kent, Jim (13 June 2014). "Sioux Reservation Has Mixed Feelings About Obama Visit". Morning Edition. NPR. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Trymaine. "No Man's Land: The Last Tribes of the Plains. As industry closes in, Native Americans fight for dignity and natural resources". MSNBC - Geography of Poverty Northwest. Retrieved 2015-09-28.>

- ↑ "NCAA Bans Indian Mascots". NewsHour. PBS. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ↑ Powell, Robert Andrew (August 25, 2005). "Florida State wins its battle to remain the Seminoles". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ↑ Kolpack, Dave (2009-09-21). "Chairman says tribe won't approve Fighting Sioux". Native American Times. Retrieved 2014-10-12.

- ↑ Conlon, Kevin (August 14, 2011). "North Dakota, NCAA spar over mascot". CNN. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ↑ "BACKGROUND ON THE DAKOTA ACCESS PIPELINE" (PDF). Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ Bravebull Allard, LaDonna (September 3, 2016). "Why the Founder of Standing Rock Sioux Camp Can't Forget the Whitestone Massacre". Yes! Magazine. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ↑ Helm, Joe (7 September 2016). "Showdown over oil pipeline becomes a national movement for Native Americans". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 Naureckas, Jim (22 September 2016). "Dakota Access Blackout Continues on ABC, NBC News". Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR).

- ↑ "Life in the Native American oil protest camps". BBC News. 2 September 2016.

- 1 2 Fulton, Deirdre (1 September 2016). "'World Watching' as Tribal Members Put Bodies in Path of Dakota Pipeline". Common Dreams.

- ↑ "Facebook 'censors' Dakota Access pipeline protest livestream – activists". RT International. 15 September 2016.

- ↑ Amundson, Barry (29 July 2016). "Standing Rock tribe sues over Dakota Access pipeline permits". Grand Forks Herald.

- ↑ Dunlap, Tiare (5 August 2016). "These Native American Youths Are Running 2,000 Miles to Protect Their Water". People.

- ↑ MacPherson, James (30 July 2016). "Standing Rock Sioux sues Corps over Bakken pipeline permits". The Des Moines Register. The Associated Press.

- ↑ Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (27 July 2016). "Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief" (PDF). In the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (1:16-cv-01534-Document 1).

- ↑ Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (4 August 2016). "Memorandum in Support of Motion for Preliminary Injunction Expedited Hearing Requested" (PDF). In the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (1:16-cv-1534-JEB).

- ↑ ICTMN Staff (28 April 2016). "Dakota Access Pipeline: Three Federal Agencies Side With Standing Rock Sioux, Demand Review". Indian Country Today Media Network.

- ↑ Healy, Jack (23 August 2016). "Occupying the Prairie: Tensions Rise as Tribes Move to Block a Pipeline". The New York Times.

- ↑ Medina, Daniel A. (September 23, 2016). "Dakota Pipeline Company Buys Ranch Near Sioux Protest Site, Records Show". NBC News. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ↑ McCauley, Lauren (5 September 2016). "'Is That Not Genocide?' Pipeline Co. Bulldozing Burial Sites Prompts Emergency Motion". Common Dreams.

- ↑ Manning, Sarah Sunshine (4 September 2016). "'And Then the Dogs Came': Dakota Access Gets Violent, Destroys Graves, Sacred Sites". Indian Country Today Media Network.

- ↑ Healy, Jack (26 August 2016). "North Dakota Oil Pipeline Battle: Who's Fighting and Why". The New York Times.

- ↑ McKibben, Bill (6 September 2016). "A Pipeline Fight and America's Dark Past". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Obama, Barack (7 September 2016). "Remarks by President Obama at YSEALI Town Hall". WhiteHouse.gov.

- ↑ Henry, Devin (9 September 2016). "Obama administration orders ND pipeline construction to stop". TheHill.

- ↑ "Company Agrees to Halt N. Dakota Pipeline Work Until Friday". NBC News. Reuters. 7 September 2016.

- ↑ Taliman, Valerie (9 September 2016). "Moments After Judge Denies DAPL Injunction, Federal Agencies Intervene". Indian Country Today Media Network.

- ↑ "Bakken pipeline opposition presents petitions to U.S. Justice Department". Radio Iowa. 15 September 2016.

- ↑ Bender, Albert (23 September 2016). "Colonial Pipeline spill confirms worries of Standing Rock Sioux water protectors". People's World.

- ↑ USA today: 2,000 veterans to give protesters a break at Standing Rock. December 2, 2016

- ↑ Goodman, Amy (4 September 2016). "Video: Dakota Access Pipeline Company Attacks Native American Protesters with Dogs and Pepper Spray". Democracy Now!.

- ↑ Levin, Sam (12 September 2016). "North Dakota arrest warrant for Amy Goodman raises fears for press freedom". The Guardian.

- ↑ McKibben, Bill (7 September 2016). "Bill McKibben: Hillary Clinton needs to take a stand on the Dakota Access Pipeline". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Kirsten, West Savali (10 September 2016). "#NoDAPL: Arrest Warrants Issued for Green Party's Stein, Baraka for Standing With Standing Rock Sioux Tribe". The Root.

- ↑ Weigel, David (14 September 2016). "Bernie Sanders pledges 'end of the exploitation of Native American people' in fight against Dakota pipeline". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Medina, Daniel A. (20 September 2016). "Standing Rock Sioux takes pipeline fight to United Nations in Geneva". NBC News.

- ↑ PBS: Army temporarily halts Dakota Access pipeline project. December 4, 2016

- ↑ NBC News: Army Corps of Engineers Denies Dakota Access Pipeline Route. December 4,2016

- ↑ Medina, Daniel A. (September 20, 2016). "Standing Rock Sioux Takes Pipeline Fight to UN Human Rights Council in Geneva". NBC News. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ↑ Archambault II, David (August 24, 2016). "Taking a Stand at Standing Rock". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Standing Rock Indian Reservation. |