Syama Prasad Mukherjee

| Shyama Prasad Mukherjee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Commerce and Industry of India | |

|

In office 15 August 1947 – 6 April 1950 | |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Nityanand Kanungo |

| Founder-President of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh | |

|

In office 1951–1952 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Mauli Chandra Sharma |

| Finance Minister of Bengal Province | |

|

In office 12 December 1941 – 20 November 1942 | |

| Prime Minister | A. K. Fazlul Huq |

| Member of Bengal Legislative Council from Calcutta University | |

|

In office 1929 – 1947[1] | |

| Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University | |

|

In office 8 August 1934 – 7 August 1938[2] | |

| Preceded by | Hassan Suhrawardy |

| Succeeded by | Muhammad Azizul Haque |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

6 July 1901 Calcutta, Bengal, British India |

| Died |

23 June 1953 (aged 51) Jammu and Kashmir, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Political party | Indian National Congress, Bharatiya Jana Sangh |

| Other political affiliations | Hindu Mahasabha |

| Spouse(s) | Sudha Devi |

| Children | 5 |

| Parents |

Ashutosh Mukherjee (father) Jogamaya Devi Mukherjee (mother) |

| Alma mater |

Presidency College Lincoln's Inn |

| Profession |

Academician Barrister Political activist |

| Religion | Hinduism |

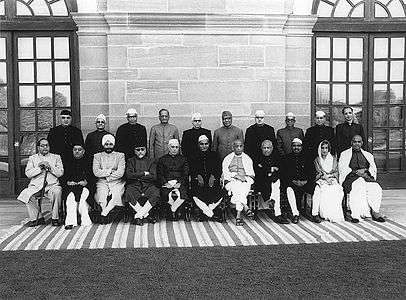

Shyama Prasad Mukherjee alternatively spelt as Syama Prasad Mookerjee (6 July 1901 – 23 June 1953) was an Indian politician, barrister and academician, who served as Minister for Industry and Supply in Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru's cabinet. After falling out with Nehru, Mukherjee quit the Indian National Congress and founded the right wing nationalist Bharatiya Jana Sangh (which would later evolve into BJP) in 1951.

Early life and academic career

Shyama Prasad Mukherjee was born in a Bengali family on 6 July 1901 in Calcutta (Kolkata).[3][4] His father was Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee, a judge of the High Court of Calcutta, Bengal, who was also Vice-Chancellor of the University of Calcutta.[5][6] His mother was Lady Jogamaya Devi Mukherjee.[4]

He enrolled in Bhawanipur's Mitra Institution in 1906 and his behavior in school was later on described favourably by his teachers. In 1917, he passed his matriculation examination and was admitted into Presidency College.[7][8] He stood first in the Inter Arts Examination in 1919[9] and graduated in English securing the first position in first class in 1921.[4] He was married to Sudha Devi on 16 April 1922.[10] Mukherjee also completed an M.A. in Bengali which he passed as a first class in 1923[9] and also became a fellow of the Senate in 1923.[11] He completed his B.L. in 1924.[4]

He enrolled as an advocate in Calcutta High Court in 1924, the same year in which his father had died.[12] Subsequently, he left for England in 1926 to study at Lincoln's Inn and was called to the English Bar in the same year.[13] At the age of 33, he became the youngest Vice-Chancellor of the University of Calcutta in 1934, and held the office till 1938.[14] It was during his term as Vice-Chancellor of the Calcutta University that Rabindranath Tagore delivered the University Convocation Address in Bengali for the first time in history and the Indian vernacular was introduced as a subject for the highest examination in the university.[15][16]

Political career before independence

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu politics |

|---|

|

|

Shyama Prasad Mukherjee started his political career in 1929, when he entered the Bengal Legislative Council as an Indian National Congress (INC) candidate representing Calcutta University.[17] However, he resigned the next year when the INC decided to boycott the legislature. Subsequently, he contested the election as an independent candidate and was elected in the same year.[18] In 1937, he was elected as an independent candidate in the elctions which brought the Krishak Praja Party-All India Muslim League coalition to power.[19][20][21] He served as the Finance Minister of Bengal Province in 1941–42 under A.K. Fazlul Haq's Progressive Coalition government which was formed on 12 December 1941 after the resignations of Muslim League ministers of the government. During his tenure, his statements against the government were censored and his movements were restricted. He wasl also prevented from visiting the Midnapore district in 1942 when severe floods caused a heavy loss of life and property. He resigned on 20 November 1942 accusing the British government of trying to hold on to India under any cost and critisiced its repressive policies against the Quit India Movement. After resigning, he mobilised support and organised relief with the help of Mahabodhi Society, Ramakrishna Mission and Marwari Relief Society.[22][23][24][25] In 1946, he was again elected as an independent candidate from the Calcutta University.[19] He was elected as a member of the Constituent Assembly of India in the same year.[26]

Leader of the Hindu Mahasabha

Mukherjee joined the Hindu Mahasabha in Bengal in 1939[27] and became its acting president in the same year.[28] He was appointed as the working president of the organisation in 1940.[8] On 11 February 1941, Mukherjee told a Hindu rally that if Muslims wanted to live in Pakistan they should "pack their bag and baggage and leave India ... (to) wherever they like".[29] He was elected as the President of Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha in 1943.[26] He remained in this position till 1946, with Laxman Bhopatkar becoming the new President in the same year.[30][31]

Mukherjee supported the partition of Bengal in 1946 to prevent the inclusion of its Hindu-majority areas in a Muslim-dominated East Pakistan.[4] A meeting held by the Mahasabha on 15 April 1947 in Tarakeswar authorised him to take steps for ensuring partition of Bengal. On 2 May 1947, he wrote a letter to Lord Mountbatten telling him that Bengal must be partitioned even if India wasn't partitioned.[32] He also opposed a failed bid for a united but independent Bengal made in 1947 by Sarat Bose, the brother of Subhas Chandra Bose, and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, a Bengali Muslim politician.[33][34]

His views were strongly affected by the Noakhali genocide in East Bengal, where mobs belonging to the Muslim League massacred Hindus in large numbers.[35]

Opposition to Quit India Movement

Following the Hindu Mahasabha's official decision to boycott the Quit India movement [36] like the communists[37][38] and the Muslim League,[39][40] Mukherjee wrote a letter to the British Government as to how they should respond to "Quit India" movement. In this letter, dated July 26, 1942 he wrote:

"Let me now refer to the situation that may be created in the province as a result of any widespread movement launched by the Congress. Anybody, who during the war, plans to stir up mass feeling, resulting internal disturbances or insecurity, must be resisted by any Government that may function for the time being" [41][42]

Mukherjee in this letter reiterated that the Fazlul Haq-led Bengal Government, along with its alliance partner Hindu Mahasabha would make every possible effort to defeat the Quit India Movement in the province of Bengal and made a concrete proposal in regard to this:

"The question is how to combat this movement (Quit India) in Bengal? The administration of the province should be carried on in such a manner that in spite of the best efforts of the Congress, this movement will fail to take root in the province. It should be possible for us, especially responsible Ministers, to be able to tell the public that the freedom for which the Congress has started the movement, already belongs to the representatives of the people. In some spheres it might be limited during the emergency. Indians have to trust the British, not for the sake for Britain, not for any advantage that the British might gain, but for the maintenance of the defense and freedom of the province itself. You, as Governor, will function as the constitutional head of the province and will be guided entirely on the advice of your Minister.[42]

Even the Indian historian R.C. Majumdar noted this fact and states:

"Shyam Prasad ended the letter with a discussion of the mass movement organised by the Congress. He expressed the apprehension that the movement would create internal disorder and will endanger internal security during the war by exciting popular feeling and he opined that any government in power has to suppress it, but that according to him could not be done only by persecution ... In that letter he mentioned item-wise the steps to be taken for dealing with the situation ..." [43]

During his resignation however, he did characterise the policies of the British government towards the movement as "repressive".[22][23]

Political career after independence

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru inducted Mukherjee into the Interim Central Government as a Minister for Industry and Supply on 15 August 1947.[44] Mukherjee began to have differences with Mahasabha after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, in which the organisation was blamed by Sardar Patel for creation of an atmosphere in the country that led to Gandhi's killing. Mukherjee suggested the organisation to suspend its political activities and left the organisation in December 1948 shortly after it did so. One of his reasons for leaving was also the rejection of his proposal to allow non-Hindus to become a member.[27][45][46][45]

Mukherjee resigned along with K.C. Neogy from the Cabinet on 8 April 1950 over a disagreement about the 1950 Delhi Pact with Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan. Mukherjee was firmly against their joint pact to establish minority commissions and guarantee minority rights in both countries as he thought it left Hindus in East Bengal to the mercy of Pakistan. While addressing a rally in Calcutta on 21 May, he stated that an exchange of population and property at governmental level on regional basis between East Bengal and Indian states of Tripura, Assam, West Bengaland Bihar was the only option in the current situation.[45][47][48]

After consultation with M. S. Golwalkar of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Mukherjee founded the Bharatiya Jana Sangh on 21 October 1951 in Delhi and he became its first President. In the 1952 elections, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) won 3 seats in the Parliament of India including Mukherjee's own seat. He had formed the National Democratic Party within the Parliament which consisted of 32 members of the Lok Sabha and 10 members of the Rajya Sabha which, however, was not recognised by the speaker as an opposition party.[49] The BJS was created with the objective of nation-building and "nationalising" all non-Hindus by "inculcating Bharatiya Culture" in them. The party was ideologically close to the RSS and widely considered the proponent of Hindu Nationalism.[50]

Opinion on special status of Jammu and Kashmir

Mukherjee was strongly opposed to Article 370 seeing as a threat to unity of the country and fought against it inside and outside of the parliament with one of the goals of Bharatiya Jana Sangh being abrogation of the article. He termed the arrangements under the article as Balkanization of India and three-nation theory of Sheikh Abdullah.[51][52][53] The state was granted its own flag along with Prime Minister whose permission was required for anyone to enter the state. In opposition to this, Mukherjee once said "Ek desh mein do Vidhan, do Pradhan aur Do Nishan nahi chalenge" (A single country can't have two constitutions, two prime ministers, and two national emblems).[54] Bharatiya Jana Sangh along with Hindu Mahasabha and Praja Parishad launched a massive Satyagraha to get the provisions removed.[51][55]

Mukherjee went to visit Kashmir in 1953 illegally, and observed a hunger strike to protest the law that prohibited Indian citizens from settling within the state and mandating that they carry ID cards.[4] Mukherjee wanted to go to Jammu and Kashmir but, because of the prevailing permit system, he was not given permission. He was arrested on 11 May at Lakhanpur while crossing the border into Kashmir illegally.[56][57] Although the ID card rule was revoked owing to his efforts, he died as a détenu on 23 June 1953 under mysterious circumstances.[58]

However, before his death, he had agreed to a formulation of autonomy for Jammu and Kashmir with further autonomy for each region of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh. In a letter on 17 February 1953 to Nehru in which he suggested:[59] "(1) Both parties reiterate that the unity of the State will be maintained and that the principle of autonomy will apply to the province of Jammu and also to Ladakh and Kashmir Valley. (2) Implementation of Delhi agreement—which granted special status to the State—will be made at the next session of Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly."

According to Balraj Madhok, who later on became the President of the Jana Sangh, the party withdrew its commitment to the State autonomy and regional autonomy under the directive from the RSS headquarters in Nagpur.[59][60]

Personal life

Shyama Prasad had 3 brothers who were: Rama Prasad who was born in 1896, Uma Prasad who was born in 1902 and Bama Prasad Mukherjee who was born in 1906. Rama Prasad became a judge in High Court of Calcutta while Uma became famed as a trekker and a travel writer. He also had 3 sisters who were: Kamala who was born in 1895, Amala who was born in 1905 and Ramala in 1908.[61] He was married to Sudha Devi for 11 years and had five children – the last one, a four-month-old son, died from diphtheria. His wife died of double pneumonia shortly afterwards in 1933 or 1934.[62][63][64] Shyama Prasad refused to remarry after her death.[65] The names of his 2 sons were Anutosh and Debatosh while that of his 2 daughters were Sabita and Arati.[66] His grandniece Kamala Sinha served as the Minister of State for External affairs in the I. K. Gujral ministry.[67]

Shyama Prasad was also affiliated with the Buddhist Mahabodhi Society. In 1942, he succeeded Dr. M.N. Mukherjee to become the President of the organisation. The relics of Gautam Buddha's two disciples Sariputta and Maudgalyayana, which were discovered in the Great Stupa at Sanchi by Sir Alexander Cunningham in 1851 and kept at British Museum, were brought back to India by HMIS Tir. A ceremony attended by politicians and leaders of many foreign countries was held on the next day at Calcutta Maidan. The relics were handed over by Jawaharlal Nehru to Mukherjee who later took these relics to Cambodia, Burma, Thailand and Vietnam. Upon his return to India, he placed the relics inside the Sanchi Stupa in November 1952.[25][68][69]

Death

Mukherjee was arrested on entering Kashmir on 11 May 1953.[70] He along with two of his arrested companions was earlier taken to Central Jail of Srinagar. Later they were transferred to a cottage outside the city. His condition started deteriorating and he started feeling pain in the back and high temperature on the night between 19 and 20 July. He was diagnosed with dry pleurisy from which he had also suffered in 1937 and 1944. The doctor Ali Mohammad prescribed him a streptomycin injection and powders, however he informed that his family physician had told him that streptomycin did not suit his system. The doctor however told him that new information about the drug had come to light and assured him that he would be fine. On 22 June, he felt pain in the heart region, started prespiring and started feeling like he was fainting. He was later shifted to a hospital and provisionally diagnosed with a heart attack. He died a day later under mysterious circumstances.[71][72][73] The state government declared that he had died on 23 June at 3:40 a.m. due to a heart attack.[74][75][76]

His death in custody raised wide suspicion across the country and demands for an independent enquiry were raised, including earnest requests from his mother, Jogamaya Devi, to Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru declared that he had inquired from a number of persons who were privy to the facts and, according to him, there was no mystery behind Mukherjee's death. Jogamaya Devi did not accept Nehru's reply and requested the setting up of an impartial enquiry. Nehru, however, ignored the letter and no enquiry commission was set up. Mukherjee's death therefore remains a matter of some controversy.[77]

Only one nurse, Rajdulari Tiku was present by his side in the hospital. According to her, when Mukherjee started crying in agony for a doctor, she fetched Dr. Jagannath Zutshi. The doctor found him in a grave condition and called Dr. Ali. Mukherjee's condition kept deteriorating and he died at 2:25 a.m.[78][79]

S.C. Das claims that Mukherjee was murdered alleging that the nurse told Mukherjee's daughter Sabita that Zutshi gave his father a poisonous powder after which he started screaming and died.[80] Atal Bihari Vajpayee claimed in 2004 that the arrest of Mukherjee in Jammu and Kashmir was a "Nehru conspiracy".[81]

Legacy

On 22 April 2010, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi's (MCD) newly constructed Rs. 650-crore building (the tallest building in Delhi) was named the Doctor Syama Prasad Mukherjee Civic Centre. The Civic Centre was inaugurated by Home Minister P. Chidambaram. The building, which is estimated to cater to 20,000 visitors per day, will also house different wings and offices of the MCD.[82] The MCD also built the Syama Prasad Swimming Pool Complex which hosted aquatic events during the 2010 Commonwealth Games held at New Delhi.[83]

On 27 August 1998, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation named a bridge after Mukherjee.[84] Delhi has a major road named after Mukherjee called Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Marg.[85] Kolkata too has a major road called Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Road.[86]

In 2001, the main research funding institute of the Government of India, CSIR, instituted a new fellowship named after him.[87] On 15 January 2012, a flyover at Mathikere in Bangalore City Limits was inaugurated and named the Dr Syamaprasad Mukherjee Flyover.[88]

In 2014, a multipurpose indoor stadium built on the Goa University campus in Goa was named after Mukherjee.[89] In 2015, the Government of India launched Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Rurban Mission to drive economic, social and infrastructure development in rural areas and create 300 rurban areas to stem increasing migration to urban areas. This scheme was operationalized in February 2016.[90][91]

The government of India approved the Shyama Prasad Mukherji Rurban Mission (SPMRM) with an outlay of Rs. 5142.08 crores on 16 September 2015. The Mission was launched by the Prime Minister on 21 February 2016 at Kurubhata, Murmunda Rurban Cluster, Rajnandgaon, Chhattisgarh.[92][93]

See also

References

- ↑ Basanta Kumar Mishra (2004). The Cripps Mission: A Reappraisal. Concept Publishing Company. p. 96.

- ↑ "Our Vice-Chancellors". University of Calcutta. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ R.P. Chaturvedi (2010). Great Personalities. Upkar Prakashan. p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 M.K. Singh (2009). Encyclopaedia Of Indian War Of Independence (1857–1947) (Set Of 19 Vols.). Anmol Publications. p. 240.

- ↑ Shreeram Chandra Dash (1968). The Constitution of India: A Comparative Study. Chaitanya Publishing. p. 566.

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates: Official Report. Rajya Sabha, Volume 81, Issues 9–15. Council of States Secretariat. 1972. p. 216.

- ↑ Tathagata Roy (2014). The Life & Times of Shyama Prasad Mookerjee. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 22.

- 1 2 Trilochan Singh (1952). Personalities: A Comprehensive and Authentic Biographical Dictionary of Men who Matter in India. [Northern India and Parliament]. Arunam & Sheel. p. 91.

- 1 2 K.V. Singh (2005). Political profiles of modern India. Vista International Publishing House. p. 275.

- ↑ Harish Chander (2000). Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, a contemporary study. Noida News. p. 75.

- ↑ Shyamaprasad Mukhopadhyay (1993). Leaves from a diary. Oxford University Press. p. vii.

- ↑ Shiri Ram Bakshi (1991). Struggle for Independence: Syama Prasad Mookerjee. Anmol Publications. p. 1.

- ↑ S.C Das (2000). The Biography of Bharat Kesri Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee with Modern Implications. Abhinav Publications. p. 22.

- ↑ Gopal Gandhi (2007). A Frank Friendship: Gandhi and Bengal: A Descriptive Chronology. Seagull Publications. p. 328.

- ↑ Khagendra Nath Sen (1970). Education and the nation: An Indian perspective. University of Calcutta. p. 225.

- ↑ Dipak Kumar Aich (1995). Emergence of Modern Bengali Elite: A Study of Progress in Education, 1854–1917. Minerva Associates. p. 27.

- ↑ Makkhan Lal (2008). Secular Politics, Communal Agenda: 1860–1953. Pragun Publication. p. 315.

- ↑ Shiri Ram Bakshi (1991). Struggle for Independence: Syama Prasad Mookerjee. Anmol Publications. p. 4.

- 1 2 Nitish K. Sengupta (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Book India. p. 393.

- ↑ Harun-or-Rashid (2003). The Foreshadowing of Bangladesh: Bengal Muslim League and Muslim Politics, 1906–1947. The University Press Limited. p. 214.

- ↑ Janam Mukherjee (2015). Hungry Bengal: War, Famine and the End of Empire. HarperCollins India. p. 60.

- 1 2 Taj ul-Islam Hashmi (1994). Peasant utopia: the communalization of class politics in East Bengal, 1920–1947. The University Press Limited. p. 221.

- 1 2 Censorship: A World Encyclopedia. Routledge. 2001. p. 1623.

- ↑ Nitish K. Sengupta (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. p. 407.

- 1 2 Vishwanathan Sharma (2011). Famous Indians of the 20th Century. V&S Publishers. p. 56.

- 1 2 Urmila Sharma, S.K. Sharma (2001). Indian Political Thought. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 381.

- 1 2 Urmila Sharma; S.K. Sharma (2001). Indian Political Thought. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 381.

- ↑ Thirumang Venkatraman (2014). Discovery of Spiritual India. Lulu. p. 46.

- ↑ Legislative Council Proceedings [BLCP], 1941, Vol. LIX, No. 6, p 216

- ↑ Sumit Sarkar, Sabyasachi Bhattacharya (2008). Towards freedom: documents on the movement for independence in India, 1946, Part 1. Oxford University Press. p. 386.

- ↑ Ron Christenson (1991). Political Trials in History: From Antiquity to the Present. Transactions Publishers. p. 160.

- ↑ Amrik Singh (2000). The Partition in Retrospect. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 219.

- ↑ Jahanara Begum (1994). The last decade of undivided Bengal: parties, politics & personalities. Minerva Associates. p. 175.

- ↑ Joya Chatterji (2002). Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 264.

- ↑ Sinha, Dinesh Chandra; Dasgupta, Ashok (2011). 1946: The Great Calcutta Killings and Noakhali Genocide. Kolkata: Himangshu Maity. pp. 278–280.

- ↑ Prabhu Bapu (2013). Hindu Mahasabha in Colonial North India, 1915–1930: Constructing Nation and History. Routledge. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-415-67165-1.

- ↑ K. Venugopal Reddy, "Working Class in 'Quit India' Movement," Indian Historical Review (2010) 37#2 pp 275–289

- ↑ D N Gupta (5 August 2008). Communism and Nationalism in Colonial India, 1939–45. SAGE Publications. p. 265. ISBN 978-81-321-0008-9.

- ↑ Martin Sieff, Shifting superpowers: the new and emerging relationship between the United States, China, and India (2009) p 21

- ↑ Syed Nesar Ahmad, Origins of Muslim consciousness in India: a world-system perspective (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1991) pp 213–15

- ↑ Mookherjee, Shyama Prasad. Leaves from a Dairy. Oxford University Press. p. 179.

- 1 2 Abdul Gafoor Abdul Majeed Noorani (2000). The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labour. LeftWord Books. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-81-87496-13-7.

- ↑ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1978). History of Modern Bengal. Oxford University Press. p. 179.

- ↑ Council of Ministers, 1947–2004: names and portfolios of the members of the Union Council of Ministers, from 15 August 1947 to 25 May 2004. Lok Sabha Secretariat. 2004. p. 50.

- 1 2 3 Kedar Nath Kumar (1990). Political Parties in India, Their Ideology and Organisation. Mittal Publications. pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Shamsul Islam (2006). Savarkar Myths and Facts. Anamaika Publishing & Distributors. p. 227.

- ↑ S. C. Das (2000). Bharat Kesri Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee with Modern Implications. Abhinav Publications. p. 143.

- ↑ Tathagata Roy (2007). A suppressed chapter in history: the exodus of Hindus from East Pakistan and Bangladesh, 1947–2006. Bookwell. p. 227.

- ↑ "Bharatiya Jana Sangh (Indian political organization) – Encyclopedia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Rafiq Dossani; Henry S. Rowen (2005). Prospects for Peace in South Asia. Stanford University Press. p. 191.

- 1 2 Hari Ram (1983). Special Status in Indian Federalism: Jammu and Kashmir. Seema Publications. p. 115.

- ↑ Kedar Nath Kumar (1990). Political Parties in India, Their Ideology and Organisation. Mittal Publications. pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Ranganathan Magadi Kumar (2009). The Literary Works of Ranganathan Magadi. Lulu. p. 595.

- ↑ A tribute to Mookerjee. Daily Excelsior. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ Yoga Raj Sharma (2003). Special Status in Indian Federalism: Jammu and Kashmir. Radha Krishna Anand & Company. p. 152.

- ↑ Harish Chander (2000). Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, a contemporary study. Noida News. p. 234.

- ↑ Rajesh Kadian (2000). The Kashmir tangle, issues & options. Vision Books. p. 120.

- ↑ Shiri Ram Bakshi (1991). Struggle for Independence: Syama Prasad Mookerjee. Anmol Publications. p. 274.

- 1 2 GreaterKashmir.com (Greater Service) (8 August 2010). "Leaf from the past". Greater Kashmir. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ GreaterKashmir.com (Greater Service) (6 February 2011). "Kashmir Policy of BJP". Greater Kashmir. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Tathagata Roy (2014). The Life & Times of Shyama Prasad Mookerjee. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 11.

- ↑ Tathagata Roy (2014). The Life & Times of Shyama Prasad Mookerjee. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 34.

- ↑ Rita Basu (1995). Dr. Shyama Prasad Mookherjee & an alternate politics in Bengal. Progressive Publishers. p. 16.

- ↑ Craig Baxter (1969). The Jana Sangh; a biography of an Indian political party. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 63.

- ↑ Raj Kumar (2014). Essays on Indian Freedom Movement. Discovery Publishing House. p. 173.

- ↑ S.C Das (2000). The Biography of Bharat Kesri Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee with Modern Implications. Abhinav Publications. p. 20.

- ↑ Rita Basu (1 January 2015). "Former MoS for External Affairs Kamala Sinha passes away". Business Standard. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ D.C. Ahir (1991). Buddhism in modern India. Sri Datguru Publications. p. 135.

- ↑ Narendra Kr. Singh (1996). nternational encyclopaedia of Buddhism: France, Volume 15. Anmol Publications. pp. 1405–1407.

- ↑ Y.G. Bhave (1 January 1995). The First Prime Minister of India. Northern Book Centre. p. 49. ISBN 978-81-7211-061-1.

- ↑ Donald Eugene Smith (2015). South Asian Politics and Religion. Princeton University Press. p. 87.

- ↑ Shiri Ram Bakshi (1991). Struggle for Independence: Syama Prasad Mookerjee. Anmol Publications. pp. 278–306.

- ↑ Harish Chander (2000). Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, a contemporary study. Noida News. pp. 22, 23, 33, 39–42, 117.

- ↑ Saroj Chakrabarty; Bidhan C. Roy (1974). With Dr. B. C. Roy and Other Chief Ministers: A Record Upto 1962. Benson's. p. 227.

- ↑ Harish Chander (2000). Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, a contemporary study. Noida News. p. 118.

- ↑ S.C.Das (1 January 1995). Bharat Kesri Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee with Modern Implications. Abhinav Publications. p. 212.

- ↑ "Family legacy and the Varun effect". rediff.com.

- ↑ Harish Chander (2000). Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, a contemporary study. Noida News. p. 67.

- ↑ Shiri Ram Bakshi (1991). Struggle for Independence: Syama Prasad Mookerjee. Anmol Publications. pp. 332, 333.

- ↑ S.C Das (2000). The Biography of Bharat Kesri Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee with Modern Implications. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 211.

- ↑ Nehru conspiracy led to Syama Prasad's death: Atal Times of India – 4 July 2004

- ↑ Sharma, Milan (22 June 2010). "Delhi gets its tallest building". NDTV. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "Delhi CM inaugurates Swimming Complex". NDTV. 18 July 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "Terrorism: Advani accuses USA of double standards". Tribune India. 28 August 1998. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Shyama Prasad Mukherji Marg is a commuter's nightmare". DNA India. 9 November 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ Ray, Saikat (22 August 2016). "Kolkata roads and greenery damaged by storms". Times of India. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research". Vol. 63. Council of Scientific and Industrial Research. 2004. p. 248.

- ↑ "Fly-over named after Dr Shyama Prasad". The New Indian Express. 16 January 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "Indoor stadium at Taleigao named after S P Mukherjee | iGoa". Navhindtimes.in. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Union Cabinet approves Shyama Prasad Mukherji Rurban Mission to drive economic, social and infrastructure development in rural areas". pib.nic.in. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

- ↑ "Excerpts of PM's Address at the launch of Shyama Prasad Mukherji Rurban Mission". pib.nic.in. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

- ↑ "Shyama Prasad Mukherji Rurban Mission (SPMRM) – Arthapedia". www.arthapedia.in. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

- ↑ "| National Rurban Mission". rurban.gov.in. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

Further reading

- Graham, B. D. (1968). "Syama Prasad Mookerjee and the communalist alternative". In D. A. Low. Soundings in Modern South Asian History. University of California Press. ASIN B0000CO7K5.

- Graham, B. D. (1990). Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics: The Origins and Development of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38348-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syama Prasad Mukherjee. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Syama Prasad Mukherjee |