Tengrism

| Part of a series on |

| Tengrism |

|---|

|

| Related movements |

| People |

Tengrism (sometimes spelled Tengriism), occasionally referred to as Tengrianism, is a Central Asian religion characterized by features of shamanism, animism, totemism, both polytheism and monotheism,[1][2][3][4][5] and ancestor worship. Historically, it was the prevailing religion of the Turks, Mongols, and Hungarians, as well as the Xiongnu and the Huns.[6][7] It was the state religion of the five ancient Turkic states: Göktürk Khaganate, Western Turkic Khaganate, Great Bulgaria, Bulgarian Empire and Eastern Tourkia (Khazaria). In Irk Bitig, Tengri is mentioned as Türük Tängrisi (God of Turks).[8] The term is perceived among Turkic peoples as referring to a national religion.

As a modern revival, Tengrism has been advocated among intellectual circles of the Turkic nations of Central Asia, including Tatarstan, Buryatia, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, in the years following the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1990s to present).[9] It is still actively practiced and undergoing an organised revival in Sakha, Khakassia, Tuva, and other Turkic nations in Siberia. Burkhanism is a movement kindred to Tengrism concentrated in Altay.

Khukh and Tengri literally mean "blue" and "sky" in Mongolian and modern Mongolians still pray to "Munkh Khukh Tengri" ("Eternal Blue Sky"). Therefore, Mongolia is sometimes poetically referred to by Mongolians as the "Land of Eternal Blue Sky" ("Munkh Khukh Tengriin Oron" in Mongolian). In modern Turkey Tengriism is also known as the Göktanrı dini, "Sky God religion",[10] Turkish "Gök" (sky) and "Tanrı" (God) corresponding to the Mongolian khukh (blue) and Tengri (sky), respectively.

According to Hungarian archaeological research, the religion of the Hungarians before Christianity (until the end of the 10th century) was Tengrism.[11]

Background

.png)

In Tengriism, the meaning of life is seen as living in harmony with the surrounding world. Tengriist believers view their existence as sustained by the eternal blue Sky, Tengri, the fertile Mother-Earth, spirit Eje, and a ruler who is regarded as the holy spirit of the Sky. Heaven, Earth, the spirits of nature and the ancestors provide every need and protect all humans. By living an upright and respectful life, a human being will keep his world in balance and maximize his personal power Wind Horse.

It is said that the Huns of the Northern Caucasus believed in two gods. One is called Tangri han (that is Tengri Khan), who is thought to be identical to the Persian Aspandiat and for whom horses were sacrificed. The other is called Kuar, whose victims are struck down by lightning.[7]

Tengriism is actively practised in Sakha, Buryatia, Tuva and Mongolia in parallel with Tibetan Buddhism and Burkhanism.[12]

In Turkey, among children, Moon is called Ay Dede (Moon The Grandfather) who is considered to be the moon-god living in the sixth floor of the sky. At nights, tales are being told about him to children by their parents for them to go to sleep. The nursery rhyme ay dede ay dede, senin evin nerede? (Grandfather Moon, Grandfather Moon, where is your home?) is popular among children.

The word Kyrgyz means We are forty in the Kyrgyz language. Regarding the importance of the number, Kyrgyzstan's flag has a symbol of 40 uniformly spaced rays. A legendary hero called Manas is believed to have 40 regional clans. Tengrist Khazars aided Heraclius by sending 40,000 soldiers during a joint Byzantine-Göktürk operation against Persians.

A number of Kyrgyz politicians are actively pushing Tengrism, to fill the ideological void. Dastan Sarygulov, secretary of state and formerly chair of the Kyrgyz state gold mining company, has established Tengir Ordo (Army of Tengri) which is a civic group that seeks to promote the values and traditions of the Tengrism.[13]

There is a Tengrist society in Bishkek, which officially claims almost 500,000 followers and an international scientific center of Tengrist studies. Both institutions are run by Dastan Sarygulov, the main theorist of Tengrism in Kyrgyzstan and a member of the Parliament.

Publications committed to the subject of Tengrism are more and more frequently published in scientific journals of human sciences in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. The partisans of this movement endeavor to influence the political circles and have succeeded in spreading their concepts into the governing bodies. Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev and even more frequently former Kyrgyz president Askar Akayev have mentioned that Tengrism is the national and “natural” religion of the Turkic peoples.

Muslim Turks views of Tengrism

The non-Muslim Turks worship of Tengri was mocked and insulted by the Muslim Turk Mahmud al-Kashgari, who wrote a verse referring to them - The Infidels - May God destroy them![14][15]

Kashgari claimed that the Prophet assisted in a miraculous event where 700,000 Yabāqu infidels were defeated by 40,000 Muslims led by Arslān Tegīn claiming that fires shot sparks from gates located on a green mountain towards the Yabāqu.[16] The Yabaqu were a Turkic people.[17]

Some symbols related to Tengriism

- Umay - Goddess of fertility and virginity

- Bai-Ulgan - Highest deity after Tengri

- Erkliğ - God of space

- Erlik - God of death

- Flag of Sakha Republic

- Flag of Kazakhstan

- Flag of Chuvashia

- Flag of Turkey

- Göktürk coins

- Tree of Life

- Öksökö

Historical Tengri

Historical Tengrism surrounded the cult of the sky god and chief deity Tengri and incorporated elements of shamanism, animism, totemism and ancestor worship. It was brought into Eastern Europe by the early Huns and Bulgars.[19] It lost its importance when the Uighuric kagans proclaimed Manichaeism the state religion in the 8th century.[20]

Tengriism also played a large part in the religious denomination of the Gok-Turk Empire and the Great Mongol Empire. The name “Gok-Turk” translates as “Celestial Turk” which directly points out to the devotion to Tengriism. In the 13th century, Genghis Khan and several generations of his followers were also Tengrian believers until his fifth generation descendent Uzbeg Khan turned to Islam in the 14th century.

The original Great Mongol Khans, although they were followers of Tengri and believed to have received a heavenly mandate to rule the world from him, were nonetheless known for their tolerance towards other confessions.[21]Möngke Khan, the fourth Great Khan of the Mongol empire, said: “We believe that there is only one God, by whom we live and by whom we die, and for whom we have an upright heart. But as God gives us the different fingers of the hand, so he gives to men diverse ways to approach Him.” (“Account of the Mongols. Diary of William Rubruck”, Religious debate in court. Documented by W. Rubruck in May 31, 1254.). In the context of the modern revival, the term is sometimes used in a much wider sense of the mythology of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples and Central Asian shamanism in general.

Tengrist movement in Central Asia

A revival of Tengrism has played a certain role in modern-day Turkic nationalism in Central Asia since the 1990s. In its early phase, it developed in Tatarstan, where a Tengrist periodical, Bizneng-Yul, appeared from 1997. The movement spread through other parts of Central Asia in the 2000s, to Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan in particular, and to a lesser extent also to Buryatia and Mongolia (Laruelle 2006).

Since the 1990s, it has also become usual in Russian language literature to use the term Тенгрианство (variously rendered tengrianism or tengrianity) in a much more general sense of "Mongolian shamanism, to the inclusion of all "esoteric traditions" native to Central Asia. Buryat scholar Irina S. Urbanaeva developed a theory of such "Tengrianist Esoteric Traditions of Central Asia" during the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting revival of national sentiment in the former Soviet Republics of Central Asia.[22]

While the Tengrist movement has very few active adherents, its discourse of the rehabilitation of a "national religion" reaches a much larger audience, especially in intellectual circles. Presenting, as it does, Islam as being foreign to the Turkic peoples, adherents are mostly found among the nationalistic parties of Central Asia. Tengrism can thus be interpreted as the Turkic version of Russian neopaganism. Another related phenomenon is that of the revival of Zoroastrianism in Tajikistan (Laruelle 2006).

By 2006, there was a Tengrist society in Bishkek, and an "international scientific centre of Tengrist studies", run by Kyrgyz businessman and politician Dastan Sarygulov. Sarygulov has also established the civic group "Tengir Ordo" ("army of Tengri"), his ideology incorporating strong features of ethnocentrism and Pan-Turkism, but his ideas did not find large support. After the Kyrgyzstani presidential elections of 2005, Sarygulov received the position of state secretary, and he also set up a special working group dealing with ideological issues.[23] Another Kyrgyz proponent of Tengrism, Kubanychbek Tezekbaev, was put on trial for inciting religious and ethnic hatred in 2011 because of statements he made in an interview, where he described Kyrgyz mullahs as "former alcoholics and murderers".[24]

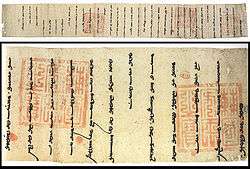

Tengriism in Arghun Khan's letter to the King of France (1289 AD)

Arghun Khan expressed the association of Tengri with imperial legitimacy and military success. The Majesty (Suu) of the Khan is a divine grace or stamp granted by Tengri to a chosen individual and through which Tengri controls the world order, in other words it is the special presence of Tengri in the person of the Great Khan. Note in this letter that the divine name 'Tengri' or 'Mongke Tengri' (Eternal Heaven) is always placed at the top of the sentence, even if the former sentence has to look like it is incomplete when the divine name is moved to top of the next sentence. In the middle of the magnified section, the sacred phrase 'Tengri-yin Kuchin' (Power of Tengri) stands completely separate from the other sentences, forming a sacred pause before being followed by the phrase 'Khagan-u Suu' (Majesty of the Khan):

Under the Power of the Eternal Tengri. Under the Majesty of the Khan (Kublai Khan). Arghun Our word. To the Ired Farans (King of France). Last year you sent your ambassadors led by Mar Bar Sawma telling Us: "if the soldiers of the Il-Khan ride in the direction of Misir (Egypt) we ourselves will ride from here and join you", which words We have approved and said (in reply) "praying to Tengri (Heaven) We will ride on the last month of winter on the year of the tiger and descend on Dimisq (Damascus) on the 15th of the first month of spring." Now, if, being true to your words, you send your soldiers at the appointed time and, worshipping Tengri, we conquer those citizens (of Damascus together), We will give you Orislim (Jerusalem). How can it be appropriate if you were to start amassing your soldiers later than the appointed time and appointment? What would be the use of regretting afterwards? Also, if, adding any additional messages, you let your ambassadors fly (to Us) on wings, sending Us luxuries, falcons, whatever precious articles and beasts there are from the land of the Franks, the Power of Tengri (Tengri-yin Kuchin) and the Majesty of the Khan (Khagan-u Suu) only knows how We will treat you favorably. With these words We have sent Muskeril (Buscarello) the Khorchi. Our writing was written while We were at Khondlon on the sixth khuuchid (6th day of the old moon) of the first month of summer on the year of the cow.

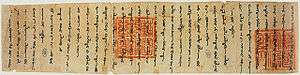

Tengriism in Arghun Khan's letter to Pope Nicholas IV (1290 AD)

Arghun Khan expressed the non-dogmatic side of Tengriism. (Note the divine name 'Mongke Tengri' (Eternal Tengri) is always at the top of the sentence in this letter, in accordance with Mongolian Tengriist writing rules):

...Your saying 'May [the Ilkhan] receive silam (baptism)' is legitimate. We say: 'We the descendants of Genghis Khan, keeping our own proper Mongol identity, whether some receive silam or some don't, that is only for Eternal Tengri (Heaven) to know (decide).' People who have received silam and who, like you, have a truly honest heart and are pure, do not act against the religion and orders of the Eternal Tengri and of Misiqa (Messiah or Christ). Regarding the other peoples, those who, forgetting the Eternal Tengri and disobeying him, are lying and stealing, are there not many of them? Now, you say that we have not received silam, you are offended and harbor thoughts of discontent. [But] if one prays to Eternal Tengri and carries righteous thoughts, it is as much as if he had received silam. We have written our letter in the year of the tiger, the fifth of the new moon of the first summer month (May 14th, 1290), when we were in Urumi.

Nestorianism and Tengriism

Tengrism is often called as Nestorianism by Christian devices.[25] Turkish Nestorian manuscripts, that have the same rune-like duct as the Old Turkic script, have been found especially in the oasis of Turfan and in the fortress of Miran.[26][27][28][29][30][31] When and by whom the Bible or any part thereof have been translated into Turkish for the first time, is completely in the dark.[32] Most of these written records in the pre-Islamic era of Central Asia are written in the Old Turkic language.[33] Nestorian Christianity also had followers among the Uighurs. In the Nestorian sites of Turfan, a fresco depicting the rites of Palm Sunday has been discovered.[34]

Principles of Tengriism

- There exists one supreme God, Tengri. He is the unknowable One who knows everything, which is why Turks and Mongols say 'Only Tengri knows' /gagtskhuu Tenger medne/. He is the Judge of people's good and bad actions, which is why it is said 'Tengri will be angry if you sin' /Tenger khilegnene/. Tengri can bless a person richly but can also utterly destroy those whom he dislikes. His actions cannot be predicted. His ways are difficult to know.

- Tengri is the intelligence and power behind all of nature. Everything is ultimately controlled by him, from the weather to the fate of individuals and nations, which is why Genghis Khan says in the Altan Tobchi: 'I have not become Lord thanks to my own bravery and strength, I have become Lord thanks to the love of our mighty father Tengri. I have defeated my enemies thanks to the assistance of our father Tengri. I have not become Khan thanks to my own all-embracing prowess. I have become Lord thanks to the love of our father Khan Tengri. I have defeated alien enemies thanks to the mercy of our father Khan Tengri.'

- There exist many other spirits or 'angels' besides Tengri. These spirits are diverse. They can be good or bad or of mixed temperament. They can be gods residing in the upper heavenly world, wandering evil spirits from the underworld, spirits of the land, water, stars and planets or spirits of the ancestors. They can be in charge of certain tribes or of certain nations. Under Tengri these spirits all have some limited influence, but it is nearly impossible for normal people to contact them. Only chosen people can contact them. Chosen people can also do the same thing these spirits do, like send destructive thunderstorms on enemy soldiers (as occurs in the Secret History of the Mongols).

- The spirits can harm people or act as agents in transmitting a message or prophecy about the future. In the Secret History of the Mongols, it is said the spirits of the land and water of Northern China were angry about the slaughter of the local population and harmed the Mongol Ogedei Khan with an illness that left him in bed unable to speak. In the Secret History, a spirit called Zaarin transmits a prophecy about the future rise of Genghis Khan.

- There is no 'one true religion'. Humanity has not reached full enlightenment. Nonetheless Tengri will not leave the guilty unpunished and the virtuous unrewarded. Those upright in spirit and righteous in thought are acceptable to Tengri, even if they followed different religions. Tengri has given different paths for man. A man may be Buddhist, Christian or Muslim, but only Tengri knows the righteous. A man may change his tribal allegiance but still be upright. Tribal customs can be changed if they are harmful to people, which is why Genghis Khan did away with many previous customs in order to ensure orderly government.

- All people are weak and therefore shortcomings should be tolerated. Different religions and customs should be tolerated. Like the life of the nomads, peoples' lives are difficult enough and subject to the pressures of nature. No one is perfect before Tengri, which is why Genghis Khan said: "If there is no means to prevent drunkenness, a man may become drunk thrice a month; if he oversteps this limit he makes himself guilty of a punishable offence. If he is drunk only twice a month, that is better — if only once, that is more praiseworthy. What could be better than that he should not drink at all? But where shall we find a man who never drinks? If, however, such a man is found, he deserves every respect"".

See also

- Heaven worship

- Manzan Gurme Toodei

- Mythology of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples

- Hungarian neopaganism

- Religion in China

- Native American religion

Notes

- ↑ The spelling Tengrism is found in the 1960s, e.g. Bergounioux (ed.), Primitive and prehistoric religions, Volume 140, Hawthorn Books, 1966, p. 80. Tengrianism is a reflection of the Russian term, Тенгрианство. It is reported in 1996 ("so-called Tengrianism") in Shnirelʹman (ed.), Who gets the past?: competition for ancestors among non-Russian intellectuals in Russia, Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-8018-5221-3, p. 31 in the context of the nationalist rivalry over Bulgar legacy. The spellings Tengriism and Tengrianity are later, reported (deprecatingly, in scare quotes) in 2004 in Central Asiatic journal, vol. 48–49 (2004), p. 238. The Turkish term Tengricilik is also found from the 1990s. Mongolian Тэнгэр шүтлэг is used in a 1999 biography of Genghis Khan (Boldbaatar et. al, Чингис хаан, 1162-1227, Хаадын сан, 1999, p. 18).

- ↑ R. Meserve, Religions in the central Asian environment. In: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume IV, The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century, Part Two: The achievements, p. 68:

- "[...] The ‘imperial’ religion was more monotheistic, centred around the all-powerful god Tengri, the sky god."

- ↑ Michael Fergus, Janar Jandosova, Kazakhstan: Coming of Age, Stacey International, 2003, p.91:

- "[...] a profound combination of monotheism and polytheism that has come to be known as Tengrism."

- ↑ H. B. Paksoy, Tengri in Eurasia, 2008

- ↑ Napil Bazylkhan, Kenje Torlanbaeva in: Central Eurasian Studies Society, Central Eurasian Studies Society, 2004, p.40

- ↑ "There is no doubt that between the 6th and 9th centuries Tengrism was the religion among the nomads of the steppes" Yazar András Róna-Tas, Hungarians and Europe in the early Middle Ages: an introduction to early Hungarian history, Yayıncı Central European University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-963-9116-48-1, p. 151.

- 1 2 Hungarians & Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early... - András Róna-Tas. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Jean-Paul Roux, Die alttürkische Mythologie, p. 255

- ↑ Saunders, Robert A. and Vlad Strukov (2010). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Federation. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. pp. 412–13. ISBN 978-0-81085475-8.

- ↑ Mehmet Eröz (2010-03-10). Eski Türk dini (gök tanrı inancı) ve Alevîlik-Bektaşilik. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Fodor István, A magyarok ősi vallásáról (About the old religion of the Hungarians) Vallástudományi Tanulmányok. 6/2004, Budapest, p. 17–19

- ↑ Balkanlar'dan Uluğ Türkistan'a Türk halk inançları Cilt 1, Yaşar Kalafat, Berikan, 2007

- ↑ McDermott, Roger. "The Jamestown Foundation: High-Ranking Kyrgyz Official Proposes New National Ideology". Jamestown.org. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ↑ Dankoff, Robert (Jan–Mar 1975). "Kāšġarī on the Beliefs and Superstitions of the Turks". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 95 (1): 70. doi:10.2307/599159. JSTOR 599159.

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ↑ Mehmet Fuat Köprülü; Gary Leiser; Robert Dankoff (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-0-415-36686-1.

- ↑ Tekin, Talat (1993). Irk bitig (the book of omens). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-447-03426-5.

- ↑ Bulgars and the Slavs followed ancestral religious practices and worshipped the sky-god Tengri. Bulgaria, Patriarchal Orthodox Church of --, p. 79, at Google Books

- ↑ Buddhist studies review, Volumes 6-8, 1989, p. 164.

- ↑ Osman Turan, The Ideal of World Domination among the Medieval Turks, in Studia Islamica, No. 4 (1955), pp. 77-90

- ↑ Irina S. Urbanaeva (Урбанаева И.С.), Шаманизм монгольского мира как выражение тенгрианской эзотерической традиции Центральной Азии ("Shamanism in the Mongolian World as an Expression of the Tengrianist Esoteric Traditions of Central Asia"), Центрально-азиатский шаманизм: философские, исторические, религиозные аспекты. Материалы международного симпозиума, 20-26 июня 1996 г., Ulan-Ude (1996); English language discussion in Andrei A. Znamenski, Shamanism in Siberia: Russian records of indigenous spirituality, Springer, 2003, ISBN 978-1-4020-1740-7, 350–352.

- ↑ Erica Marat, Kyrgyz Government Unable to Produce New National Ideology, 22 February 2006, CACI Analyst, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute.

- ↑ RFE/RL 31 January 2012.

- ↑ A. S. Amanjolov, History of ancient Türkic Script, Almaty 2003, p.305

- ↑ Georg Stadtmüller, Saeculum , Band 1, K. Alber Publishing, 1950, p.302

- ↑ University of Bonn. Department of Linguistics and Cultural Studies of Central Asia, Issue 37, VGH Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH Publishing, 2008, p.107

- ↑ Theodore Brieger, Bernhard Bess, Society for Church History, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Volume 115, issues 1-3, W. Kohlhammer Publishing, 2004, p.101

- ↑ Jens Wilkens, Wolfgang Voigt, Dieter George, Hartmut-Ortwin Feistel, German Oriental Society, List of Oriental Manuscripts in Germany, Volume 12, Franz Steiner Publishing, 2000, p.480

- ↑ Volker Adam, Jens Peter Loud, Andrew White, Bibliography old Turkish Studies, Otto Harrassowitz Publishing, 2000, p.40

- ↑ Ural-Altaic Yearbooks, Volumes 42-43, O. Harrassowitz Publishing, 1970, p.180

- ↑ Materialia Turcica, Volumes 22-24, Brockmeyer Publishing Studies, 2001, p.127

- ↑ "Turfan research: Scripts and languages in pre-Islamic Central Asia, Academy of Sciences of Berlin and Brandenburg, 2011" (in German). Bbaw.de. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ M. S. Asimov, The historical,social and economic setting, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1999, p.204

References

- Brent, Peter (1976). The Mongol Empire: Genghis Khan: His Triumph and his Legacy. London: Book Club Associates.

- Richtsfeld, Bruno J. (2004). "Rezente ostmongolische Schöpfungs-, Ursprungs- und Weltkatastrophenerzählungen und ihre innerasiatischen Motiv- und Sujetparallelen". Münchner Beiträge zur Völkerkunde. Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Museums für Völkerkunde München. 9. pp. 225–274.