Twenty-seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

|

The Twenty-seventh Amendment (Amendment XXVII) to the United States Constitution prohibits any law that increases or decreases the salary of members of Congress from taking effect until the start of the next set of terms of office for Representatives. It is the most recent amendment to be adopted, but one of the first proposed.

It was submitted by Congress to the states for ratification on September 25, 1789, along with eleven other proposed amendments. While ten of these twelve proposals were ratified in 1791 to become the Bill of Rights, what would become the Twenty-seventh Amendment and the proposed Congressional Apportionment Amendment did not get ratified by enough states for them to also come into force with the first ten amendments. The proposed congressional pay amendment was largely forgotten until 1982 when Gregory Watson researched it as a student at the University of Texas at Austin and began a new campaign for its ratification.[1] The amendment eventually became part of the United States Constitution on May 5, 1992, completing a record-setting ratification period of 202 years, 7 months, and 10 days.[2]

Text

The amendment as proposed by Congress in 1789 reads as follows:

No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.[3]

Historical background

Several states raised the issue of Congressional salaries as they debated whether to ratify the 1787 Constitution.

The North Carolina ratifying convention proposed several amendments to the Constitution including the following: "The laws ascertaining the compensation of senators and representatives, for their services, shall be postponed in their operation until after the election of representatives immediately succeeding the passing thereof; that excepted which shall first be passed on the subject." Virginia's ratifying convention recommended the identical amendment.[4]

New York's declaration of ratification was accompanied by a similar amendment proposal: "That the Compensation for the Senators and Representatives be ascertained by standing law; and that no alteration of the existing rate of Compensation shall operate for the Benefit of the Representatives, until after a subsequent Election shall have been had."[4]

Proposal by Congress

This amendment was one of several proposed amendments to the Constitution introduced first in the House on June 8, 1789, by Representative James Madison of Virginia. Madison's original intent was that it be added to the end of the first sentence in Article I, Section 6, Clause 1 of the Constitution, "The Senators and Representatives shall receive a Compensation for their Services, to be ascertained by Law, and paid out of the Treasury of the United States".[5] This, along with Madison's other proposals were referred to a committee consisting of one representative from each state. After emerging from committee, the full House debated the issue and, on August 24, 1789, passed it and sixteen other articles of amendment. The proposals went next to the Senate, which made 26 substantive alterations. On September 9, 1789, the Senate approved a culled and consolidated package of twelve articles of amendment.[6] Nothing was changed in this amendment.

On September 21, 1789, a House–Senate conference committee convened to resolve numerous differences between the House and Senate Bill of Rights proposals. On September 24, 1789, the committee issued its report, which finalized 12 proposed amendments for the House and Senate to consider. The House agreed to the conference report that same day, and the Senate concurred the next day.[7]

What would become the Twenty-seventh Amendment was listed second among the twelve proposals sent to the states for their consideration on September 25, 1789. Ten of these, numbers 3–12, were ratified fifteen months later and are known collectively as the Bill of Rights. The remaining proposal, the Congressional Apportionment Amendment, has not been ratified by enough states to make it part of the Constitution.

Revival of interest

This proposed amendment was largely forgotten until Gregory Watson, an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, wrote a paper on the subject in 1982.[4] After receiving a 'C' grade on his paper, by an instructor who regarded his idea as "unrealistic",[8][9] Watson started a new push for ratification with a letter-writing campaign to state legislatures.[10]

The U.S. Supreme Court, in its decision Coleman v. Miller, 307 U.S. 433 (1939), had ruled that the validity of state ratifications of a constitutional amendment is political in nature—and so not a matter properly assigned to the judiciary. It also held that as a political question, it was up to Congress to determine if an amendment with no time limit for ratification was still viable after an extended lapse of time based on "the political, social and economic conditions which have prevailed during the period since the submission of the amendment".

When Watson began his campaign in early 1982, he was aware of ratification by six states and he erroneously believed that Virginia's 1791 approval was the last action taken by the states. He learned in 1983 that Ohio had approved it in 1873 and learned in 1984 that Wyoming had done the same in 1978.[11] Watson did not know, until after the amendment's adoption, that Kentucky had ratified the amendment in 1792.[12]

In April 1983, Maine became the first state to ratify the amendment as a result of Watson's campaign, followed by Colorado in April 1984. Numerous state legislatures followed suit. Michigan's ratification on May 7, 1992, provided what was believed to be the 38th state ratification required for the archivist to certify the amendment[4]—Kentucky's 1792 ratification having been overlooked.

Ratification by the states

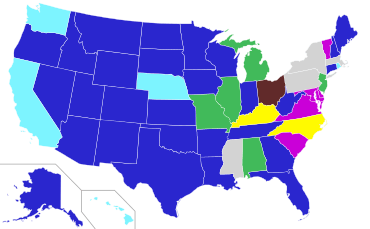

The following states ratified the Twenty-seventh Amendment:

- Maryland – December 19, 1789

- North Carolina – December 22, 1789 (reaffirmed July 4, 1989[13])

- South Carolina – January 19, 1790

- Delaware – January 28, 1790

- Vermont – November 3, 1791

- Virginia – December 15, 1791

- Kentucky – June 27, 1792[14] (reaffirmed March 21, 1996)

- Ohio – May 6, 1873 (as a means of protest against the 1873 "Salary Grab Act"[10])

- Wyoming – March 6, 1978 (as a protest against a congressional pay raise[10])

- Maine – April 27, 1983

- Colorado – April 22, 1984

- South Dakota – February 21, 1985

- New Hampshire – March 7, 1985 (after rejection – January 26, 1790[15])

- Arizona – April 3, 1985

- Tennessee – May 28, 1985

- Oklahoma – July 1, 1985

- New Mexico – February 14, 1986

- Indiana – February 24, 1986

- Utah – February 25, 1986

- Arkansas – March 13, 1987

- Montana – March 17, 1987

- Connecticut – May 13, 1987

- Wisconsin – July 15, 1987

- Georgia – February 2, 1988

- West Virginia – March 10, 1988

- Louisiana – July 7, 1988

- Iowa – February 9, 1989

- Idaho – March 23, 1989

- Nevada – April 26, 1989

- Alaska – May 6, 1989

- Oregon – May 19, 1989

- Minnesota – May 22, 1989

- Texas – May 25, 1989

- Kansas – April 5, 1990

- Florida – May 31, 1990

- North Dakota – March 25, 1991

- Alabama – May 5, 1992

- Missouri – May 5, 1992

- Michigan – May 7, 1992

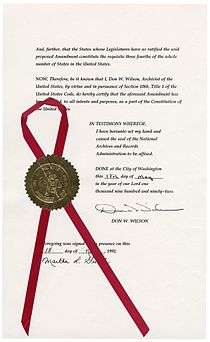

On May 18, 1992, the Archivist of the United States, Don W. Wilson, certified that the amendment's ratification had been completed.[16][17] The certification was officially recorded the next day in the Federal Register.[18] Michigan's May 7, 1992, ratification was believed to be the 38th state, but it later came to light that the Kentucky General Assembly had ratified the amendment during that state's initial month of statehood,[14] making Missouri the state to finalize the amendment's addition to the Constitution.[lower-alpha 1][2]

The amendment was later ratified by:

- 40. New Jersey – May 7, 1992 (After rejection – November 20, 1789[15])

- 41. Illinois – May 12, 1992

- 42. California – June 26, 1992

- 43. Rhode Island – June 10, 1993[20] (After rejection – June 7, 1790[15])

- 44. Hawaii – April 29, 1994[20]

- 45. Washington – April 6, 1995[20]

- 46. Nebraska – April 1, 2016[21]

Four states have not ratified the Twenty-seventh Amendment: Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York, and Pennsylvania.

Affirmation of ratification

In certifying that the amendment had been duly ratified, the Archivist of the United States had acted under statutory authority granted to his office by the Congress under Title 1, section 106b of the United States Code, which states:

Whenever official notice is received at the National Archives and Records Administration that any amendment proposed to the Constitution of the United States has been adopted, according to the provisions of the Constitution, the Archivist of the United States shall forthwith cause the amendment to be published, with his certificate, specifying the States by which the same may have been adopted, and that the same has become valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the Constitution of the United States.

The response in Congress was sharp. Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia scolded Wilson for certifying the amendment as ratified without congressional approval. Although Byrd supported Congressional acceptance of the amendment, he contended that Wilson had deviated from "historic tradition" by not waiting for Congress to consider the validity of the ratification, given the extremely long lapse of time since the amendment had been proposed.[18] Speaker of the House Tom Foley and others called for a legal challenge to the amendment's unusual ratification.

On May 20, 1992, under the authority recognized in Coleman, and in keeping with the precedent first established regarding the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, each house of the 102nd Congress passed its own version of a concurrent resolution agreeing that the amendment was validly ratified, despite the unorthodox period of more than 202 years for the completion of the task. The Senate's approval of the resolution was unanimous (99 to 0) and the House vote was 414 to 3.[10]

Cost-of-living adjustments

Congressional cost-of-living adjustments (COLA) have been upheld against legal challenges based on this amendment. In Boehner v. Anderson,[22] the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled that the Twenty-seventh Amendment does not affect annual COLAs. In Schaffer v. Clinton,[23] the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ruled that receiving such a COLA does not grant members of the Congress standing in federal court to challenge that COLA; the Supreme Court did not hear either case and so has never ruled on this amendment's effect on COLAs.

See also

- List of amendments to the United States Constitution

- List of proposed amendments to the United States Constitution

- United States Bill of Rights

Notes

- ↑ Alabama and Missouri both ratified the amendment on May 5, 1992, with the Archivist of the United States then recording Alabama as the 36th and Missouri the 37th state to ratify the amendment.[19]

References

Citations

- ↑ Berke, Richard (May 8, 1992). "1789 Amendment Is Ratified But Now the Debate Begins". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- 1 2 The U.S. Constitution and Constitutional Law. Britannica Educational Publishing. 2012. pp. 105–108. ISBN 9781615307555.

- ↑ "The Bill of Rights: A Transcription". Archives.gov. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Bernstein, Richard B. (1992). "The Sleeper Wakes: The History and Legacy of the Twenty-Seventh Amendment". Fordham Law Review. 61 (3): 497–557. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ↑ Gordon Lloyd. "Madison's Speech Proposing Amendments to the Constitution, June 8, 1789". TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Ashland, Ohio: The Ashbrook Center at Ashland University. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ↑ Labunski, Richard E. (2006). James Madison and the struggle for the Bill of Rights. Oxford University Press. pp. 235–237. ISBN 978-0-19-518105-0.

- ↑ Schwartz, Bernard (2002). The Great Rights of Mankind: A History of the American Bill of Rights (First Rowman & Littlefield ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 186. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ↑ Frantzich, Stephen E. (2008). Citizen Democracy: Political Activists in a Cynical Age (3rd ed.). New York: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 12–14. ISBN 9780742564459.

- ↑ "27: Congressional pay raises". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. November 27, 2002. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Dean, John W. (September 27, 2002). "The Telling Tale of the Twenty-Seventh Amendment". FindLaw. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ↑ Bomboy, Scott (7 May 2016). "How a C-grade college term paper led to a constitutional amendment". National Constitution Center. Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- ↑ Rowley, Sean (2 September 2014). "27th amendment aimed at congressional pay". Tahlequah Daily Press. Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- ↑ North Carolina General Assembly House Bill 1052 / S.L. 1989-572

- 1 2 Chapter XII, June Session 1792. The Statute Law of Kentucky: With Notes, Prælections, and Observations on the Public Acts... Frankfort: William Hunter. 1809. pp. 76–77.

- 1 2 3 James J. Kilpatrick, ed. (1961). The Constitution of the United States and Amendments Thereto. Virginia Commission on Constitutional Government. p. 64.

- ↑ Congressional Record of the 102nd Congress, Volume 138 – Part 9, May 19, 1992, p. 11656.

- ↑ Constitutional Pay Amendment, Dept. of Justice, Ops. 16 of the Office of Legal Council, May 13, 1992.

- 1 2 Michaelis, Laura (May 23, 1992). "Both Chambers Rush to Accept 27th Amendment on Salaries". Congressional Quarterly. p. 1423.

- ↑ Kyvig, David E. (1996). Explicit and Authentic Acts: Amending the U.S. Constitution, 1776-1995. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. pp. 467, 546n17.

- 1 2 3 "The Organic Laws of the United States of America". Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ↑ Young, JoAnne (1 April 2016). "It took awhile, but add Nebraska's name to the list". Lincoln Journal-Star. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ↑ 30 F.3d 156 (D.C. Cir. 1994)

- ↑ 240 F.3d 878 (10th Cir. 2001)

Sources

- The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation. (Senate Document No. 103–6). (Johnny H. Killian and George A. Costello, Eds.), Washington, DC: United States Government Publishing Office.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Twenty-seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- National Archives: Twenty-seventh Amendment

- Congressional resolutions recognizing ratification:

- Certification of the 27th Amendment at National Archives Online Public Access