Tywyn

| Tywyn | |

Tywyn High Street |

|

Tywyn |

|

| Population | 3,264 |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | SH585004 |

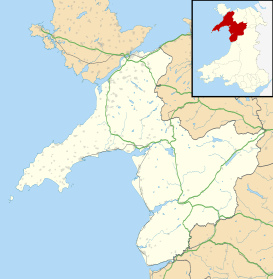

| Principal area | Gwynedd |

| Ceremonial county | Gwynedd |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | TYWYN |

| Postcode district | LL36 |

| Dialling code | 01654 |

| Police | North Wales |

| Fire | North Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| EU Parliament | Wales |

| UK Parliament | Dwyfor Meirionnydd |

| Welsh Assembly | Dwyfor Meirionnydd |

Coordinates: 52°34′55″N 4°05′20″W / 52.582°N 4.089°W

Tywyn (/ˈtaʊ.ɪn/; Welsh: [ˈtəʊ.ᵻn]), formerly Towyn,[1] is a town and seaside resort on the Cardigan Bay coast of southern Gwynedd, Wales. It was previously in the historic county of Merionethshire. It is famous as the location of the Cadfan Stone, a stone cross with the earliest known example of written Welsh, and the home of the Talyllyn Railway.

Name

The name derives from the Welsh tywyn ("beach, seashore, sand-dune"): extensive sand dunes are still to be found to the north and south of the town. The place-name element tywyn is found in many other parts of Wales, most notably Towyn near Abergele.[2] The town is sometimes referred to in Welsh as Tywyn Meirionnydd (with Meirionnydd here probably referring to the cantref of that name, and later the historic county). In English, during the late 19th century and until the middle of the 20th century, the town was sometimes called Towyn-on-Sea. With the standardization of the orthography of the Welsh language in the first part of the 20th century, the spelling Tywyn came to dominate, and was accepted as the official name of the town in both languages in the 1970s.

History

Tywyn was the location of the first religious community administered by the Breton saint Cadfan upon his arrival in Gwynedd, prior to his departure to found a monastery on Bardsey Island off the Llyn Peninsula. The church contains some early material (see below).

Location

The town's historic centre lies about a kilometre from the beach, around the church of St Cadfan's. In the second half of the 19th century the town expanded considerably, mainly towards the sea.

To the north of the town lie the reclaimed salt marshes of Morfa Tywyn and Morfa Gwyllt, beyond which lie the Broad Water lagoon and the mouth of the Afon Dysynni. To the north-east lie the rich farmland of Bro Dysynni and the village of Bryn-crug, and to the east the hills of Craig y Barcud and Craig Fach-Goch. To the south towards Aberdyfi is the mouth of the Afon Dyffryn Gwyn and Penllyn Marshes.

The Tywyn coastal defence scheme, a £7.6m civil engineering project, to provide a new rock breakwater above the low-tide level, rock groynes, and rock revetment to protect 80 sea-front properties was officially unveiled by Jane Davidson, the Minister for Environment, Sustainability and Housing in the Welsh Assembly Government, on 24 March 2011.[3]

Demography and language

At the time of the 2001 census, 40.5% of the population were recorded as Welsh speakers. By the 2011 census this had decreased to 37.5%. These relatively high figures (given the town's demography) reflect the fact that both Welsh and English are used as the medium of instruction in Ysgol Penybryn, the town's primary school. An Estyn inspection report in 2010 noted that about 11% of the children at the school came from homes where Welsh was the main language.[4]

The town's Welsh dialect has several notable features, with one Victorian observer stating that three languages were spoken there: English, Welsh and 'Tywynaeg'.[5] During the 1860s, in the town's British School, a 'Welsh stick' (a version of the Welsh Not) was used to punish children who were caught speaking Welsh.[6] Yet Welsh was the dominant language in Tywyn until the middle of the 20th century. Tywyn is now a very anglicized town, with the majority of its population (52.8%) being born in England according to the 2011 UK census. Likewise, slightly more respondents claimed an English-only identity (35.0%) than a Welsh-only identity (33.7%).[7]

Transport and tourism

The church is of interest for two mediaeval effigies, and for a stone inscribed with what is believed to be the oldest known writing in the Welsh language, dating back to the 8th century AD, and rescued from a local gateway in the 18th century.[8]

Improved transport links during the 19th century increased Tywyn's appeal as a tourist destination. During the early decades of the century, a creek of the river Dysynni allowed ships to approach the town's northern fringes, where a shipbuilding yard was to be found. The draining of the salt marsh and the channeling of the river brought this industry to an end[9] but during the early part of the century the town was made more accessible by building new roads along the coast to Aberdyfi and Llwyngwril.

The railway arrived in the mid-1860s (firstly as the Aberystwith and Welsh Coast Railway, then as Cambrian Railways), and had a significant effect on the town. Tywyn railway station opened in 1863. The station is still open, and is served by the Cambrian Line.

Slate-quarrying in the Abergynolwyn area led to the building in 1865 of the Talyllyn Railway, a narrow-gauge line designed to carry slates to Tywyn. Two stations were opened in the town. Tywyn Wharf railway station was originally opened to enable slates to be unloaded onto a wharf adjacent to the main railway line. It is now the Talyllyn's western terminus and principal station. Pendre railway station was originally the passenger station, and now houses the locomotive and carriage sheds and works.

Notable visitors who stayed at Tywyn in the 19th century include:

- Thomas Love Peacock (1811, at Botalog)[10]

- Thomas Fremantle, 1st Baron Cottesloe (1818)

- Ignatius Spencer (1818)[11]

- Charles Darwin (1819, at Plas Edwards)[12]

- William Morris (1875)[13]

- Elizabeth Blackwell (exact date uncertain, at Brynarfor)[14]

The beach and its extensive promenade have long been key attractions. In 1877, a pier was built at Tywyn, but the structure only lasted a few months.[15] The street called 'Pier Road', which leads from the town to the beach, offers a suggestion as to its location. The promenade was completed in 1889 at the cost of some £30,000, paid for by John Corbett (1817-1901) of Ynysymaengwyn.

There has been extensive bungalow and caravan development in the vicinity.[8]

Other industries

Apart from tourism, agriculture has long been the most important industry in the area. Lead and copper used to be mined in the town's hinterland.

The Marconi Company built a Long Wave receiver station in Tywyn in 1914, working in duplex with the high-power transmitter station near Waunfawr. In 1921 the Tywyn and Waunfawr stations initiated a transatlantic wireless telegraph service with a similar RCA wireless transmitting station in New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA and RCA's receiver station in Belmar, New Jersey. This new transatlantic service replaced Marconi's obsolete transatlantic telegraph station in Clifden, Ireland following its 1922 destruction during the Irish Civil War.[16]

For most of the 20th century, the armed forces were a significant presence in Tywyn. The town was a major training ground for the amphibious warfare landings in the Second World War and had a strategic war base. Abandoned pillboxes may still be seen on the coast to the south of the town. The links with the armed forces came to an end when the Joint Service Mountain Training Centre at Morfa Camp closed in 1999.[17]

Facilities and notable features

Much of the town's infrastructure was put in place by an industrialist from the English Midlands, John Corbett, who in the 1870s decided to develop the town into a major tourist resort to rival Torquay. As well as constructing a row of boarding houses and a grand esplanade, he developed the water and sewerage system. He gave land and money for a new Market Hall, built to celebrate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897. He paid for Brynarfor (formerly a private school originally called the Towyn Academy and then Brynarvor Hall School) to be opened as 'Towyn Intermediate School' in 1894. He refurbished the Corbet Arms Hotel (from then on spelled with two 't's), and also contributed to the Assembly Room (1893), now Tywyn Cinema. Plaques commemorating his generosity may still be seen on the north end of the promenade and on the Market Hall. Another commemorative plaque was on Brynarfor (now demolished), and his portrait was hung there when the school first opened. However, the anticipated grand watering-place never took off, and these additions to the town were never matched.[8]

In 1912, a drill hall was built in the Pen-dre area of the town for the Territorial Army (the 7th Battalion the Royal Welsh Fusiliers). The hall, now known as Neuadd Pendre, has recently been renovated, mainly with money from the National Lottery Big Lottery Fund and the Welsh Government.[18] The hall houses a 3-manual 9-rank Wurlitzer Organ which was originally installed in a cinema in Woolwich in 1937.[19]

After the First World War money was raised to build both the Tywyn Cottage Hospital (opened in 1922) and the Tywyn Institute (opened by David Lloyd George in 1926). The hospital is still in operation, but the institute is now closed.[20] It was the location of the town's library before a new library building was built next to it in the early 1970s.

The main schools in Tywyn are the primary school, Ysgol Penybryn, and the secondary school, Ysgol Uwchradd Tywyn.

Local places of interest include Craig yr Aderyn (Bird Rock), Castell y Bere and Tal-y-llyn Lake. Hen Dyffryn Gwyn is a Grade II listed building dating from 1640 which retains many of its original features.[21]

Religion

For many centuries, St Cadfan's church was the only place of worship in the town, but since the 19th century there have been several.

Following the Methodist Revival, the Calvinistic Methodists established a cause in Tywyn at the end of the 18th century. Bethel Calvinistic Methodist Church (Welsh-speaking Presbyterian Church of Wales) was established in 1815. The current chapel was built in 1871 and modified in 1887.[22] The chapel closed in early 2010 but services are still held in the vestry.

Bethany Calvinistic Methodist Chapel (English-speaking Presbyterian Church of Wales), was also built in 1871 as one of the 'Inglis Côs' ('English cause') chapels that were advocated by Lewis Edwards and fiercely criticised by Emrys ap Iwan. It was opened in part with a view to attracting the increasing numbers of visitors who were coming to Tywyn following the opening of the railway and who previously had been provided for only by the English services at St Cadfan's.[23] The noted pacifist George Maitland Lloyd Davies was minister of Bethany and also of Maethlon Chapel in nearby Cwm Maethlon (Happy Valley) between 1926 and 1930.

Ebeneser (Welsh-speaking Wesleyan Methodist Church in Wales) was first built between 1817 and 1820, with the current building dating from 1883.[24] John Cadvan Davies (1846–1923), Archdruid of Wales in 1923, was minister of Ebeneser between 1889 and 1892.[25]

Bethesda Independent Chapel (Welsh-speaking Congregationalist) was first built in 1820, enlarged in 1865 and rebuilt again in 1892.[26] It closed in January 2010.[27]

Tywyn Baptist Church (English-speaking) was built in its present form in 1991.[28]

The Church of St David is the town's Roman Catholic church and is part of Dolgellau Deanery. In its grounds is a sculpture of St David in Welsh slate by John Skelton.

Sport

In Samuel Lewis's A Topographical Dictionary of Wales (1833) it is reported that popular horse races were held on land to the north of the town every September. Between 1904 and 1947, Towyn Golf Club (originally the Towyn-on-Sea Golf Club) was also located on land to the north of the town.[29]

The Towyn-on-Sea club opened with a 10-hole course in 1904, in 1906 a further eight holes were added. Attempts were made to re-establish the club following the Second World War but these proved unsuccessful.[30]

In the past Tywyn has had a rugby union team, and it now shares a football team with neighbouring Bryn-crug (Tywyn & Bryncrug F.C.), playing their home matches in the village of Bryncrug. It also has a cricket club, Tywyn and District CC and a hockey team known as Dysynni Hockey Club. Also based in Tywyn is the Bro Dysynni Athletics Club.

Notable people

- See Category:People from Tywyn

- Arthur ap Huw – vicar of St Cadfan's between 1555 and his death in 1570, notable patron of Welsh poets, and translator of counter-Reformation literature into Welsh.

- Evan Evans (Ieuan Fardd/Ieuan Brydydd Hir, 1731–88), poet and scholar, was curate of St Cadfan's between 1772 and 1777. During his time at Tywyn he was the bardic teacher of David Richards (Dafydd Ionawr) (1751–1827) from Glanymorfa near Bryn-crug.

- Edward Ernest Hughes (7 February 1877 – 23 December 1953), the first professor of history at University College, Swansea, was born in Tywyn, the son of a local policeman.

- Griffith Hughes (1707 – c. 1758) clergyman from the parish of Tywyn, author of The Natural History of Barbados.

- John Ceiriog Hughes ('Ceiriog', 1832–1887), poet, was stationmaster at Tywyn for a short period from 1870.

- Joseph David Jones (1827–1870, 'Eos Powys'), musician, was schoolmaster at Tywyn British School from 1851 to 1855. It was at Tywyn that he met his wife, Catherine Daniel of Penllyn.

- Sir Henry Haydn Jones (1863-1950), MP for Merioneth, was the son of Joseph David Jones, and spent most of his life in Tywyn

- John Daniel Jones (1865-1942), the renowned Congregationalist minister, was another son of Joseph David Jones.

- Owen Wynne Jones ('Glasynys', 1828-1870), Welsh cleric, antiquary, author, and poet, died at Tywyn on 4 April 1870.

Arthur ap Huw's nephew David Johns (sometimes known as Dafydd Johns, David Jones or David ap John, fl. 1572-98) was another important figure in the Welsh Renaissance.[31] A great-grandson of Hywel ap Siencyn, he copied an important manuscript of cywyddau (British Library Additional MS 14866) which includes several poems to the Ynysymaengwyn family.

Later additions to this manuscript contain several eighteenth-century Welsh poems, some of which relate to the Owen and Corbet family of Ynysymaengwyn and to the Reverend Edward Morgan.[32] Edward Morgan (d. 1749), a native of Llangelynnin, was vicar of St Cadfan's from 1717. He was educated at Jesus College, Oxford, corresponded with Lewis Morris (1701–1765), and was one of the eighteenth-century owners of David Johns's manuscript.[33] His brother John Morgan composed an elegy to Vincent Corbet of Ynysymaengwyn.

In 1826, Edward Jones of Tywyn published Marwolaeth Abel, a Welsh translation of Der Tod Abels by the Swiss poet Solomon Gessner.

Since around 1860 the Anwyl of Tywyn Family have lived outside the town at Tŷ Mawr. Their ancestral home was at Parc near Penrhyndeudraeth. The Anwyls are direct male line descendants of Rhodri ab Owain Gwynedd and as such are members of the House of Aberffraw and represent a surviving fragment of medieval Welsh royalty.

References

- ↑ The local branch of the Royal Air Forces Association still employs the name "Towyn and Aberdovey".

- ↑ The two places now use different spellings, partly for reasons of differentiation. Confusion between the two still occurs, however: Sat-nav mix up leaves pupils in Towyn not Tywyn, BBC News, 19 April 2013.

- ↑ £7.6m coastal defence scheme opened at Tywyn - Welsh Assembly Government.

- ↑ Williams, William Edwards. 2010. A report on the quality of education in Ysgol Penybryn, Tywyn, Gwynedd, p. 1.

- ↑ D. S. Thomas, 'Yr Ail Draethawd', in P. H. Hughes et al. (ed.), Ystyron Enwau ... ym Mhlwyfi Towyn, Llangelynin, Llanfihangel y Pennant, Talyllyn, a Phennal (Caernarfon, 1907), p. 122.

- ↑ Meirionnydd Archives, Gwynedd Archives Service, Towyn British School Log Book, Merionethshire, 1863-76, Gathering the Jewels: The website for Welsh heritage and culture.

- ↑ Census statistics for Tywyn are available at Office for National Statistics, Neighbourhood Statistics: Tywyn Ward.

- 1 2 3 Simon Jenkins, 2008, Wales: churches, houses, castles, Allen Lane, London, p. 244

- ↑ George Smith, Tywyn Coastal Protection Scheme Archaeological Assessment (Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Report No.555, 2004), p. 6 and fig. 3.

- ↑ Madden, Mary and Lionel. 1986. 'Edward Scott, Bodtalog, and his literary circle: Thomas Love Peacock, James and John Stuart Mill and William Owen Pughe'. National Library of Wales Journal, 24.3, pp. 352-7.

- ↑ Rev. Father Pius a Spiritu Sancto. 1866. The life of Father Ignatius of St. Paul, Passionist (The Hon. & Rev. George Spencer). London 1866, pp. 45–7.

- ↑ Lucas, Peter. 2001. 'Three weeks which now appear like three months: Charles Darwin at Plas Edwards'. National Library of Wales Journal, 32.2, pp. 123-46.

- ↑ Henderson, Philip. 1950. ed. The Letters of William Morris to his Family and Friends. London: Longmans, p. 69.

- ↑ Elizabeth Blackwell Letters, circa 1850-1884.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Jeremy. 1984. Tywyn Pier. Journal of the Merioneth Historical and Record Society, 9.4, pp. 457-71.

- ↑ Williams, Harri. 1999. Marconi and his wireless stations in Wales. Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 0-86381-536-7; Hogan Jr, John L. A New Marconi Transatlantic Wireless Service. Electrical World, 29 August 1914.

- ↑ Jones, Rees Ivor. 2000. The Military in Tywyn 1795-1999: The Warlike Side of a Small Welsh Seaside Town. Tywyn: the author.

- ↑ Neuadd Pendre Social Centre.

- ↑ The Tywyn Wurlitzer.

- ↑ BBC Online, Tywyn report highlights jobs, homes and tourism needs.

- ↑ "Hen Dyffryn Gwyn, Tywyn". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ↑ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Bethel Chapel (Welsh Calvinistic Methodist), Tywyn.

- ↑ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Bethany Chapel (English Presbyterian and Calvinistic Methodist), Tywyn.

- ↑ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Ebenezer Methodist Chapel (Wesleyan), Tywyn.

- ↑ Morgan, Gwylfa H. 1983. Canmlwyddiant Ebeneser Tywyn 1983. Tywyn.

- ↑ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Bethesda Welsh Independent Chapel, Tywyn.; Jones, Richard. 1970. Dathlu agor Capel Bethesda Tywyn, Mehefin 21, 1820. Abertawe: Gwasg John Penry.

- ↑ Capel arall yn cau, Dail Dysynni, Rhagfyr 2009/Ionawr 2010.

- ↑ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Tywyn Baptist Church.

- ↑ Gwynedd Archives: Meirionnydd Record Office, Towyn Golf Club Records.

- ↑ 'Towyn-on-Sea Golf Club, Gwynedd', Golf's Missing Links.

- ↑ Roberts, Brynley F. 2004. ‘Johns , David (fl. 1572–1598)’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 18 Feb 2012.

- ↑ Owen, Bob, 1962. Cipolwg ar Ynysmaengwyn a'i deuluoedd. Journal of the Merioneth Historical and Record Society, 4.2, pp. 97-118.

- ↑ Davies, William. ‘Morganiaid Llangelynin Meirion’, Yr Haul (1939), 93–8, 151–2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tywyn. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tywyn. |

- Visit Tywyn

- Tywyn an illustrated guide

- bbc.co.uk North West Wales: Tywyn

- Marconi Long Wave Receiving site in Tywyn

- www.geograph.co.uk : photos of Tywyn and surrounding area