Battle of Passchendaele

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Passchendaele (Third Battle of Ypres, Flandernschlacht and Deuxième Bataille des Flandres) was a major campaign of the First World War, fought by the Allies against the German Empire.[lower-alpha 1] The battle took place on the Western Front, from July to November 1917, for control of the ridges south and east of the Belgian city of Ypres in West Flanders, as part of a strategy decided by the Allies at conferences in November 1916 and May 1917. Passchendaele lay on the last ridge east of Ypres, 5 miles (8.0 km) from a railway junction at Roulers, which was vital to the supply system of the German 4th Army.[lower-alpha 2] The next stage of the Allied plan was an advance to Thourout–Couckelaere, to close the German-controlled railway running through Roulers and Thourout.

Further operations and a British supporting attack along the Belgian coast from Nieuwpoort, combined with Operation Hush (an amphibious landing), were to have reached Bruges and then the Dutch frontier. The resistance of the 4th Army, unusually wet weather, the onset of winter and the diversion of British and French resources to Italy, following the Austro-German victory at the Battle of Caporetto (24 October – 19 November), enabled the Germans to avoid a general withdrawal, which had seemed inevitable in early October. The campaign ended in November, when the Canadian Corps captured Passchendaele, apart from local attacks in December and the new year. In 1918, the Battle of the Lys and the Fifth Battle of Ypres were fought before the Allies occupied the Belgian coast and reached the Dutch frontier.

A campaign in Flanders was controversial in 1917 and has remained so. The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, opposed the offensive, as did General Ferdinand Foch the French Chief of the General Staff. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commanding the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), did not receive approval for the Flanders operation from the War Cabinet until 25 July. Matters of dispute by the participants, writers and historians since the war, have included the wisdom of pursuing an offensive strategy in the wake of the Nivelle Offensive, rather than waiting for the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France.

The choice of Flanders over areas further south or the Italian front, the climate and weather in Flanders, the choice of General Hubert Gough and the Fifth Army to conduct the offensive, debates over the nature of the opening attack and between advocates of shallow and deeper objectives, have also been controversial. The passage of time between the Battle of Messines (7–14 June) and the Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July, the opening move of the Third Battle of Ypres), the extent to which the internal troubles of the French armies motivated British persistence with the offensive, the effect of the weather, the decision to continue the offensive in October and the human cost of the campaign on the soldiers of the German and British armies, have also been argued over ever since.

Background

Flanders 1914–1917

Belgian independence had been recognised in the Treaty of London (1839) which created a sovereign and neutral state.[3] The German invasion of Belgium on 4 August 1914, in violation of Article VII of the treaty, was the reason given by the British government for declaring war on Germany.[4] British military operations in Belgium began with the arrival of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) at Mons on 22 August. On 16 October, the Belgians and some French reinforcements began the defence of the French Channel ports and what remained of unoccupied Belgium at the Battle of the Yser. Operations further south in Flanders commenced after reciprocal attempts by the French and German armies to turn their opponents' northern flank through Picardy, Artois and Flanders, known as the Race to the Sea, reached Ypres. On 10 October, Lieutenant-General Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the German General Staff since mid-September, ordered an attack towards Dunkirk and Calais, followed by a turn south to gain a decisive victory.[5] When the offensive failed, Falkenhayn ordered the capture of Ypres to gain a local advantage. By 12 November, the attempt in the First Battle of Ypres had also failed, at a cost of 160,000 German casualties and was stopped on 18 November.[6]

In December 1914, the British Admiralty began discussions with the War Office, for a combined operation to occupy the Belgian coast to the Dutch frontier, with an attack along the coast combined with a landing at Ostend. Eventually the British were obliged to participate in the French offensives further south.[7] Large British offensive operations in Flanders were not possible in 1915, due to the consequent lack of resources.[8] The Germans conducted their own Flanders offensive at the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April – 15 May 1915), making the Ypres salient more costly to defend.[9] Sir Douglas Haig succeeded Sir John French as Commander-in-Chief of the BEF on 19 December 1915.[10] A week after his appointment, Haig met Vice-Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, who emphasised the importance of obtaining control of the Belgian coast, to end the threat posed by German U-boats. Haig was sceptical of a coastal operation, believing that a landing from the sea would be far more difficult than anticipated and that an advance along the coast would require so much preparation, that the Germans would have ample warning. Haig preferred an advance from Ypres, to bypass the flooded area around the Yser and the coast, before a coastal attack (Operation Hush) was attempted, to clear the coast to the Dutch border.[7]

In January 1916, Haig ordered General Herbert Plumer to plan offensives against Messines Ridge, Lille and Houthoulst Forest.[11] General Henry Rawlinson was also ordered to plan an attack from the Ypres Salient on 4 February. Planning by Plumer continued but the demands of the Battles of Verdun and the Somme absorbed the offensive capacity of the BEF.[12] On 15 and 29 November 1916, Haig met the French commander-in-chief Joseph Joffre and the other Allies at Chantilly. An offensive strategy to overwhelm the Central Powers was agreed, with attacks planned on the Western, Eastern and Italian fronts, by the first fortnight in February 1917.[13] A meeting in London of the British Admiralty and General Staff urged that the Flanders operation be undertaken in 1917 and Joffre replied on 8 December, agreeing to the proposal for a Flanders campaign after the spring offensive.[14] The plan for a year of steady attrition on the Western Front, with the main effort in the summer being made by the BEF, was scrapped by the new French Commander-in-Chief Robert Nivelle and the French government in preference for a decisive battle, to be conducted in February by the French army, with the British contribution becoming a preliminary operation, the Battles of Arras.[15]

Nivelle planned an operation in three parts, with preliminary offensives to pin German reserves by the British at Arras and the French between the Somme and the Oise, a French breakthrough offensive on the Aisne, then pursuit and exploitation. The plan was welcomed by Haig with reservations, which he addressed on 6 January. Nivelle agreed to a proviso that if the first two parts of the operation failed to lead to part three, they would be stopped so that the British could move their main forces north for the Flanders offensive, which Haig argued was of great importance to the British government.[16] Haig wrote on 23 January that it would take six weeks to move British troops and equipment from the Arras front to Flanders, and on 14 March he noted that the attack on Messines Ridge could be made in May. On 21 March, he wrote to Nivelle that it would take two months to prepare the attacks from Messines to Steenstraat but that the Messines attack could be ready in 5–6 weeks. On 16 May, Haig wrote that he had divided the Flanders operation into two phases, one to take Messines Ridge and the main attack several weeks later.[17] British determination to clear the Belgian coast took on more urgency, after the Germans resumed unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917.[18]

Small operations took place in the Ypres salient in 1916, some being German initiatives to distract the Allies from the preparations for the offensive at Verdun and later attempts to divert Allied resources from the Battle of the Somme. Other operations were begun by the British to regain territory or to evict the Germans from ground overlooking their positions. Engagements took place on 12 February at Boesinghe and on 14 February at Hooge and Sanctuary Wood. There were actions from 14–15 February and 1–4 March at The Bluff, 27 March – 16 April at the St. Eloi Craters and the Battle of Mont Sorrel from 2–13 June.[19] In January 1917, the Second Army (II Anzac, IX, X and VIII corps) held the line in Flanders from Laventie to Boesinghe, with eleven divisions and up to two in reserve. There was much trench mortaring, mining and raiding by both sides and from January to May, the Second Army had 20,000 casualties. In May, reinforcements began moving to Flanders from the south; the II Corps headquarters and 17 divisions had arrived by the end of the month.[20]

Strategic background

Several British and French operations took place beyond Flanders during the Third Battle of Ypres, intended to assist Allied operations at Ypres, by obstructing the flow of munitions and reinforcements to the 4th Army in Belgium and to exploit opportunities created by the German need to economise elsewhere. German offensives in Russia and against Italy were postponed several times as demand for men and munitions in Flanders, left little available for other operations. The French army was able to continue its recuperation after the Nivelle Offensive, conduct a limited offensive at Verdun in August and the Battle of La Malmaison in October.[21] The relative passivity of the French on the Aisne front after the Nivelle Offensive and its causes were known in general by the Germans but the 7th Army had only just held on and its local reserves were then "sucked into the whirlpool of Flanders".[22]

Prelude

Geography and climate

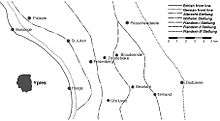

The front line around Ypres had changed relatively little since the end of the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April – 25 May 1915).[23] The British held the city, while the Germans held the high ground of the Messines–Wytschaete ridge to the south, the lower ridges to the east and the flat ground to the north.[24][lower-alpha 3] The Ypres front was a salient bulging into German positions, overlooked by German artillery on the higher ground. It was difficult for the British forces to gain ground observation of the German rear areas east of the ridges.[26]

In Flanders, sands, gravels and marls predominate, in places covered by silts. The coastal strip is sand but a short way inland, the ground rises to the vale of Ypres, which before 1914 was a flourishing market garden.[27] Ypres is 20 metres (66 ft) above sea level; Bixshoote 4 miles (6.4 km) to the north is at 8.5 metres (28 ft). To the east the land is at 20–25 metres (66–82 ft) for several miles, with the Steenbeek river at 15 metres (49 ft) near St Julien. There is a low ridge from Messines, 80 metres (260 ft) at its highest point, running north-east past "Clapham Junction" at the west end of Gheluvelt plateau ( 2 1⁄2 miles from Ypres at 65 metres (213 ft) and Gheluvelt (above 50 metres (160 ft)) to Passchendaele, ( 5 1⁄2 miles from Ypres at 50 metres (160 ft)) declining from there to a plain further north. Gradients vary from negligible, to 1:60 at Hooge and 1:33 at Zonnebeke.[28]

Underneath the soil is London clay, sand and silt; according to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission categories of sand, sandy soils and well-balanced soils, Messines ridge is well-balanced soil and the ground around Ypres is sandy soil.[29] The ground is drained by many streams, canals and ditches which need regular maintenance. Since 1914 much of the drainage had been destroyed, although some parts had been restored by Land Drainage Companies brought from England. The area was considered by the British to be drier than Loos, Givenchy and Plugstreet Wood further south.[30] A 1989 study of weather data recorded at Lille, 16 miles (26 km) from Ypres from 1867–1916, showed that August was more often dry than wet, that there was a trend towards dry autumns (September–November) and that average rainfall in October had decreased over the previous fifty years.[31][lower-alpha 4]

British plans

Preparations for operations in Flanders began in 1915, with the doubling of the Hazebrouck–Ypres rail line and the building of a new line from Bergues–Proven which was doubled in early 1917. Progress on roads, rail lines, railheads and spurs in the Second Army zone was continuous and by mid-1917, gave the area the most efficient supply system of the BEF.[42] Several plans and memoranda for a Flanders offensive were produced between January 1916 and May 1917, in which the writers tried to relate the offensive resources available to the terrain and the likely German defence. In early 1916, the importance of the capture of the Gheluvelt plateau for an advance further north was emphasised by Haig and the army commanders.[43]

On 14 February 1917, Colonel C. N. Macmullen of GHQ proposed that the plateau be taken by a mass tank attack, reducing the need for artillery; in April a reconnaissance by Captain G. le Q Martel found that the area was unsuitable for tanks.[44] On 9 February, General Rawlinson, commander of the Fourth Army, suggested that Messines Ridge could be taken in one day and that the capture of the Gheluvelt plateau should be fundamental to the attack further north. He suggested that the southern attack from St. Yves to Mont Sorrel should come first and that Mont Sorrel to Steenstraat should be attacked within 48–72 hours. After discussions with Rawlinson and Plumer and the incorporation of Haig's changes, Macmullen submitted his memorandum on 14 February. With amendments the memorandum became the GHQ 1917 plan.[45]

On 1 May 1917, Haig wrote that the Nivelle Offensive had weakened the German army but that an attempt at a decisive blow would be premature.[46] An offensive at Ypres would continue the wearing-out process, on a front where the Germans could not refuse to fight. Even a partial success would improve the tactical situation in the Ypres salient, reducing the exceptional "wastage" which occurred even in quiet periods.[47] In early May, Haig set the timetable for the Flanders offensive, with 7 June the date for the preliminary attack on Messines Ridge.[48] A week after the Battle of Messines Ridge, Haig gave his objectives to his Army commanders: wearing out the enemy, securing the Belgian coast and connecting with the Dutch frontier by the capture of Passchendaele ridge, followed by an advance on Roulers and Operation Hush, an attack along the coast with an amphibious landing. If manpower and artillery were insufficient, only the first part of the plan might be fulfilled. On 30 April, Haig told Gough the Fifth Army commander, that he would lead the "Northern Operation" and the coastal force, although Cabinet approval for the offensive was not granted until 21 June.[49][lower-alpha 5]

German defences in Flanders

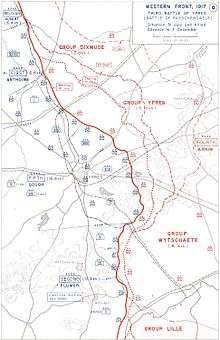

The 4th Army held a front of 25 miles (40 km) with three Gruppen, composed of a corps headquarters and a varying complement of divisions; Group Staden, based on the headquarters of the Guards Reserve Corps was added later. Group Dixmude held 12 miles (19 km) with four front divisions and two Eingreif divisions, Group Ypres held 6 miles (9.7 km) from Pilckem to Menin Road with three front divisions and two Eingreif divisions and Group Wijtschate held a similar length of front south of the Menin road, with three front divisions and three Eingreif divisions. The Eingreif divisions were stationed behind the Menin and Passchendaele ridges. About 5 miles (8.0 km) further back, were four more Eingreif divisions and 7 miles (11 km) beyond them, another two in Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL) reserve.[52]

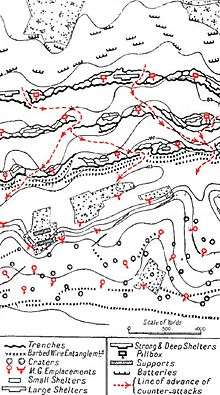

The Germans were anxious that the British would attempt to exploit the victory at the Battle of Messines, with an advance to the Tower Hamlets spur, beyond the north end of Messines Ridge. On 9 June, Crown Prince Rupprecht proposed a withdrawal to the Flandern line east of Messines. Construction of defences began but were terminated after Fritz von Loßberg was appointed as the new Chief of Staff of the 4th Army.[53] Loßberg rejected the proposed withdrawal to the Flandern line and ordered that the current front line east of the Oosttaverne line be held rigidly. To this end, the Flandern Stellung (Flanders Position) along Passchendaele Ridge, in front of the Flandern line, would become the Flandern I Stellung and a new Flandern II Stellung would run west of Menin and north to Passchendaele. Construction of a Flandern III Stellung east of Menin northwards to Moorslede was also begun. From mid-1917, the area east of Ypres was defended by six German defensive positions, the front line, Albrecht Stellung (second line), Wilhelm Stellung (third line), Flandern I Stellung (fourth line), Flandern II Stellung (fifth line) and Flandern III Stellung (under construction). In between the German defence positions lay the Belgian villages of Zonnebeke and Passchendale.[54]

On 25 June, Erich Ludendorff, the First Quartermaster General, suggested to Crown Prince Rupprecht that Group Ypres should withdraw to the Wilhelm Stellung, leaving only outposts in the Albrecht Stellung. On 30 June, the army group Chief of Staff, General von Kuhl, suggested a withdrawal to the Flandern I Stellung along Passchendaele ridge, meeting the old front line in the north near Langemarck and close to Armentières in the south. Such a withdrawal would avoid a hasty retreat from Pilckem Ridge and force the British into a time-consuming redeployment. Lossberg disagreed, believing that the British would launch a broad front offensive, that the ground east of the Sehnen line was easy to defend, that the Menin road ridge could be held, if it was made the Schwerpunkt (point of main effort) of the German defensive effort. Pilckem Ridge deprived the British of ground observation over the Steenbeek Valley, while the Germans could see the area from Passchendaele Ridge, allowing German infantry to be supported by observed artillery fire. Lossberg's judgement was accepted and no withdrawal was made.[55]

Messines Ridge: 7–17 June

The first stage in the British plan was a preparatory attack on the German positions south of Ypres at Messines Ridge. The German positions had observation over Ypres and unless captured, would enable observed enfilade artillery-fire against a British attack eastwards from the salient.[56] Since mid-1915, the British had been covertly digging mines under the German positions on the ridge. By June 1917, 21 mines had been filled with nearly 1,000,000 long tons (1,000,000 t) of explosives.[57] The Germans knew the British were mining and had taken some counter-measures but they were taken by surprise at the extent of the British effort.[58] Two of the mines failed to detonate but 19 went off on 7 June, at 3:10 a.m. British Summer Time. The final objectives were largely gained before dark and the British had fewer losses than expected, the plan having provided for up to 50 percent in the initial attack. As the infantry advanced over the far edge of the ridge, German artillery and machine-guns east of the ridge began to fire and the British artillery was less able to suppress them.[59] Fighting continued on the lower slopes on the east side of the ridge until 14 June.[60] The offensive removed the Germans from the dominating ground on the southern face of the Ypres salient, which the 4th Army had held since the First Battle of Ypres (19 October – 22 November 1914).[61]

Kerensky offensive

The Russian army launched the Kerensky Offensive to honour the agreement struck with its allies, at the Chantilly meeting of 15–16 November 1916. After a brief period of success from 1–19 July, the German strategic reserve of six divisions, captured Riga from 1–5 September 1917. In Operation Albion (September–October 1917), the Germans took the islands at the mouth of the Gulf of Riga and the British and French commanders on the Western Front, had to reckon on the German western army (Westheer) being strengthened by reinforcements from the Eastern Front, in late 1917.[62] Haig wished to exploit the diversion of German forces in Russia for as long as it continued and urged that the maximum amount of manpower and munitions be committed to the battle in Flanders.[63]

Battles

First phase, July–August

Haig selected Gough to command the offensive on 30 April and on 10 June, Gough took over the Ypres salient north of Messines Ridge. Gough planned an offensive based on the GHQ 1917 plan and the instructions he had received from Haig.[64] On the understanding that Haig wanted a more ambitious version, Gough held meetings with his Corps commanders on 6 and 16 June, where the third objective, which included the Wilhelm Stellung (third line), a second-day objective in earlier plans, was added to the two objectives due to be taken on the first day. A fourth objective was also given for the first day but was only to be attempted at the discretion of divisional and corps commanders, in places where the German defence had collapsed.[65]

The British attack was not a breakthrough operation, because Flandern I Stellung, the fourth German defensive position, lay 10,000–12,000 yards (9,100–11,000 m) behind the front line and was not an objective on the first day. The Fifth Army plan was more ambitious than the Plumer version, which had involved an advance of 1,000–1,750 yards (910–1,600 m).[66] Major-General J. Davidson, Director of Operations at GHQ, wrote in a memorandum that there was "ambiguity as to what was meant by a step-by-step attack with limited objectives" and suggested reverting to a 1,750 yards (1,600 m) advance, to increase the concentration of British artillery.[67] Gough stressed the need to plan to exploit an opportunity to take ground left temporarily undefended; this was more likely in the first attack, which would have the benefit of long preparation. After discussions at the end of June, Haig and Plumer, the Second Army commander, endorsed the Fifth Army plan.[68]

Battle of Pilckem Ridge

The British attack began at 3:50 a.m. on 31 July; the attack was to commence at dawn but a layer of unbroken low cloud, meant that it was still dark.[69] The main attack of the offensive, by II Corps across the Ghelveult Plateau to the south, confronted the principal German defensive concentration of artillery, ground-holding and Eingreif divisions. The attack had most success on the left (north), in front of XIV Corps and the French First Army. In this section of the front, the Entente forces advanced 2,500–3,000 yards (2,300–2,700 m), up to the line of the Steenbeek stream. In the centre of the British attack, XVIII Corps and XIX Corps pushed forward to the line of the Steenbeek to consolidate and sent reserve troops towards the Green and Red lines (on the XIX Corps front), an advance of about 4,000 yards (3,700 m). Group Ypres counter-attacked the flanks of the British break-in, supported by all available artillery and aircraft at about midday. The German counter-attack was able to drive the three British brigades back to the black line with 70 percent losses, where the German counter-attack was stopped by mud, artillery and machine-gun fire.[70]

Capture of Westhoek

II Corps attacked on 10 August, to capture the rest of the black line on the Gheluvelt plateau. The advance succeeded but German artillery fire and infantry counter-attacks isolated the infantry of the 18th Division, which had captured Glencorse Wood. At about 7:00 p.m., German infantry attacked behind a smokescreen and recaptured all but the north-west corner of the wood, only the 25th Division gains on Westhoek Ridge being held.[71] Albrecht von Thaer, Staff Officer at Group Wytshchate, noted that casualties after 14 days in the line averaged 1,500–2,000 men, compared to the Somme 1916 average of 4,000 men and that German troop morale was higher than in 1916.[72]

Battle of Hill 70

The Battle of Hill 70, was a subsidiary operation by the Canadian Corps against five divisions of the German 6th Army. The battle took place on the outskirts of Lens, Pas-de-Calais, from 15–25 August. Kuhl wrote later that it was a costly defeat and "wrecked" the plan for relieving divisions which had been "fought-out" (exhausted) in Flanders.[73]

Battle of Langemarck

The Battle of Langemarck was fought from 16–18 August; the Fifth Army headquarters was influenced by the effect that delay would have on Operation Hush, which needed the high tides at the end of August or it would have to be postponed for a month. Gough intended that the rest of the green line, just beyond the Wilhelm Stellung (German third line), from Polygon Wood to Langemarck, to be taken and the Steenbeek crossed further north.[74] In the II Corps area, the disappointment of 10 August was repeated, with the infantry managing to advance, then being isolated by German artillery and (except in the 25th Division area near Westhoek) and forced back to their start line by German counter-attacks. Attempts by the German infantry to advance further were stopped by British artillery fire with many losses.[75] The advance further north in the XVIII Corps area, retook and held the north end of St Julien and the area south-east of Langemarck, while XIV Corps captured Langemarck and the Wilhelm Stellung, north of the Ypres–Staden railway near the Kortebeek. The French First Army conformed, pushing up to the Kortebeek and St. Jansbeck stream west of the northern stretch of the Wilhelm Stellung, where it crossed to the east side of the Kortebeek.[76]

Subsidiary operations

Smaller British attacks from 19–27 August also failed to hold captured ground, although a XVIII Corps attack on 19 August succeeded. Exploiting observation from higher ground to the east, the Germans were able to inflict many losses on the British divisions holding the new line beyond Langemarck. After two fine dry days from 17–18 August, XIX Corps and XVIII Corps began pushing closer to the Wilhelm Stellung (third line). On 20 August, an operation by British tanks, artillery and infantry captured strong points along the St. Julien–Poelcappelle road and two days later, more ground was gained by the two corps but they were still overlooked by the Germans in the un-captured part of the Wilhelm Stellung.[77] II Corps resumed operations to capture Nonne Bosschen, Glencorse Wood and Inverness Copse around the Menin Road on 22–24 August, which failed and were costly to both sides.[78] Gough laid down a new infantry formation of skirmish lines to be followed by "worms" on 24 August. Cavan noted that pill-box defences required broad front attacks, so as to engage them simultaneously.[79] The British general offensive intended for 25 August, was delayed because of the failure of previous attacks to hold ground, following the Battle of Langemarck and then postponed due to more bad weather.[80] Attacks on 27 August were minor operations, which were costly and inconclusive. Haig called a halt to operations amidst tempestuous weather.[81]

French attack at Verdun

Petain had committed the French Second Army to an attack at Verdun in mid-July, in support of the operations in Flanders. The attack was delayed, partly due to the mutinies which had affected the French army after the failure of the Nivelle Offensive and also because of a German attack at Verdun from 28–29 June, which captured some of the ground intended as a jumping-off point for the French attack. A French counter-attack on 17 July re-captured the ground, the Germans regained it on 1 August, then took ground on the east bank on 16 August.[82] The battle began on 20 August and by 9 September, had taken 10,000 prisoners. Fighting continued sporadically into October, adding to the German difficulties on the Western Front and elsewhere. Ludendorff wrote:

On the left bank, close to the Meuse, one division had failed ... and yet both here and in Flanders everything possible had been done to avoid failure ... The French army was once more capable of the offensive. It had quickly overcome its depression.— Ludendorff: Memoirs[83]

yet there was no German counter-attack, because the local Eingreif divisions were in Flanders.[84]

Second phase: September–October

The German 4th Army had defeated the British advance to all of the 31 July objectives during August but high casualties and sickness caused by the ground conditions, endless bombardments and air attacks worsened the manpower shortage that the German defensive strategy for 1917 was intended to alleviate.[85] Haig transferred command of the offensive to General Plumer, the Second Army commander on 25 August and moved the northern boundary of the Second Army closer to the Ypres–Roulers railway. More heavy artillery was sent to Flanders from the armies further south and placed opposite the Gheluvelt plateau.[86] Plumer continued the development of British attacking methods, which had also taken place in the Fifth Army, during the slow and costly progress in August, against the German defence-in-depth and the unusually wet weather. After a pause of about three weeks, Plumer intended to capture Gheluvelt plateau in four steps, with six days between each step to allow time to bring forward artillery and supplies.[87] Each attack was to have limited geographical objectives like the attacks in August, with infantry brigades re-organised to attack the first objective with one battalion each and the final one with two battalions.[88]

Plumer arranged for much more medium and heavy artillery to be added to the creeping bombardment, which had been impossible with the amount of artillery available to Gough.[88] The revised attack organisation was intended to have more infantry attacking on narrower fronts, to a shallower depth than the attack of 31 July. The quicker and shorter advances were intended to be consolidated on tactically advantageous ground (particularly on reverse slopes), with the infantry in contact with their artillery and air support, ready to repulse counter-attacks.[86] The faster tempo of the operations was intended to add to German difficulties in replacing tired divisions through the transport bottlenecks behind the German front.[89] The pause in British operations while Plumer moved more artillery into the area of the Gheluvelt plateau, helped to mislead the Germans, Albrecht von Thaer, Staff Officer at Group Wijtschate wrote that it was "almost boring".[72] At first, Kuhl doubted that the offensive had ended but by 13 September, had changed his mind and despite reservations allowed two divisions, thirteen heavy batteries and twelve field batteries of artillery, three fighter squadrons and four other air force units to be transferred from the 4th Army.[90]

German defensive changes

Instead of setting objectives 1–2 miles (1.6–3.2 km) distant as on 31 July, the British planned an advance of approximately 1,500 yards (1,400 m), without the disadvantages of rain soaked ground and poor visibility encountered in August. The advances were much quicker and the final objective was reached a few hours after dawn, which confounded the German counter-attack divisions. Having crossed 2 miles (3.2 km) of mud, the Eingreif divisions found the British already established along a new defence line, with the forward battle zone and its weak garrison gone beyond recapture.[91] After the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge, the German defensive system was changed, beginning a resort to expedients which lasted for the rest of the battle. In August, German front-line divisions had two regiments of three battalions each deployed forward, with the third regiment in reserve. The front battalions had needed to be relieved much more frequently than expected, due to the power of British attacks, constant artillery fire and the weather, which caused replacement units to become mixed up with ones holding the front, rather than operate as formed bodies. Reserve regiments had not been able to intervene early enough, leaving front battalions unsupported until Eingreif divisions arrived, some hours after the commencement of the attack.[92]

After another severe defeat on 26 September, the German commanders made more changes to the defensive dispositions of the infantry and altered their counter-attack tactics, which had been negated by Plumer's more conservative form of limited attacks. In July and August, German counter-attack (Eingreif) divisions had engaged in a manner analogous to an advance to contact during mobile operations, which had given the Germans several costly defensive successes.[93] The counter-attacks in September had been assaults on reinforced field positions, due to the restrained nature of British infantry advances. The fine weather in early September had greatly eased British supply difficulties, especially in the delivery of huge amounts of artillery ammunition. Immediately after their infantry advances, the British had made time to establish a defence in depth, behind standing barrages. The British attacks took place in dry clear weather, with increased air support over the battlefield for counter-attack reconnaissance, contact patrol and ground-attack operations. Systematic defensive artillery support was forfeited by the Germans, due to uncertainty over the position of their infantry, just when the British infantry benefitted from the opposite. German counter-attacks were defeated with many casualties and on 28 September, Albrecht von Thaer, staff officer at Group Wytschaete, wrote that the experience was "awful" and that he did not know what to do.[94][72]

Ludendorff ordered a strengthening of forward garrisons by the ground-holding divisions. All machine-guns, including those of the support and reserve battalions of the front line regiments, were sent into the forward zone, to form a cordon of four to eight guns every 250 yards (230 m).[95] The ground holding divisions were reinforced by the Stoss regiment of an Eingreif division being moved up behind each front division into the artillery protective line behind the forward battle zone, to launch earlier counter-attacks while the British were consolidating. The bulk of the Eingreif divisions were to be held back and used for a methodical counter-stroke on the next day or the one after and for counter-attacks and spoiling attacks between British offensives.[96][97][lower-alpha 6] Further changes of the 4th Army defensive methods were ordered on 30 September. Operations to increase British infantry losses in line with the instructions of 22 September were to continue. Gas bombardments of forward British infantry and artillery positions, were to be increased whenever the winds allowed. Every effort was to be made to induce the British to reinforce their forward positions, where the German artillery could engage them.[99] Between 26 September and 3 October, the Germans attacked at least 24 times.[21] Operation Hohensturm, a bigger German methodical counter-attack, intended to recapture the area around Zonnebeke was planned for 4 October.[100]

Battle of the Menin Road Ridge

The British plan for the battle fought from 20–25 September, included more emphasis on the use of heavy and medium artillery to destroy German concrete pill-boxes and machine-gun nests, which were more numerous in the battle zones being attacked and to engage in more counter-battery fire. The British had 575 heavy and medium and 720 field guns and howitzers, having more than doubled the quantity of artillery available at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge.[101] Aircraft were to be used for systematic air observation of German troop movements, to avoid the failures of previous battles, where too few aircraft crews had been burdened with too many duties and had flown in bad weather.[102]

On 20 September, the Allies attacked on a 14,500 yards (13,300 m) front and captured most of their objectives, to a depth of about 1,500 yards (1,400 m) by mid-morning.[103] The Germans made many counter-attacks, beginning around 3:00 p.m. until early evening, all of which failed to gain ground or made only a temporary penetration of the new British positions. The German defence had failed to stop a well-prepared attack made in good weather.[104] Minor attacks took place after 20 September, as both sides jockeyed for position and reorganised their defences. A mutually-costly attack by the Germans on 25 September, recaptured pillboxes at the south western end of Polygon Wood. Next day, the German positions near the wood were swept away in the Battle of Polygon Wood.[105]

Counter-attack, 25 September

Two regiments of the German 50th Reserve Division attacked on a 1,800-yard (1,600 m) front, on either side of the Reutelbeek, supported by aircraft and 44 field and 20 heavy batteries of artillery, four times the usual amount of artillery for a division. The German infantry managed to advance on the flanks, for about 100 yards (91 m) near the Menin road and 600 yards (550 m) north of the Reutelbeek, close to Black Watch Corner, supported by artillery-observation and ground-attack aircraft and a box-barrage fired behind the British front-line, which isolated the British defenders from reinforcements and cut off the supply of ammunition. Return-fire from the 33rd Division (Major-General Reginald Pinney) and the 15th Australian Brigade of the 5th Australian Division (Major-General Talbot Hobbs) along the southern edge of Polygon wood, forced the attackers under cover around some of the Wilhelm Stellung pillboxes, near Black Watch Corner, at the south-western edge of Polygon Wood. German attempts to reinforce the attacking troops failed, due to British artillery observers isolating the advanced German troops with artillery barrages.[106]

Plumer ordered the attack scheduled for 26 September to go ahead but modified the objectives of the 33rd Division. The 98th Brigade was to advance and cover the right flank of the 5th Australian Division and the 100th Brigade was to re-capture the lost ground further south. The 5th Australian Division advance the next day began with uncertainty as to the security of the right flank; the attack of the depleted 98th Brigade was delayed and only managed to reach Black Watch Corner, 1,000 yards (910 m) short of its objectives. Reinforcements moved forward into the 5th Australian Division area to the north and attacked south-westwards at noon, as a frontal attack was made from Black Watch Corner without artillery support, because troops were known to be still holding out. The attack succeeded by 2:00 p.m. and later in the afternoon, the 100th Brigade re-took the ground lost north of the Menin road. Casualties in the 33rd Division were so great that it was relieved on 27 September by the 23rd Division, which had only been withdrawn on the night of 24/25 September.[107]

Battle of Polygon Wood

The Second Army altered its Corps frontages soon after the attack of 20 September, for the next effort (26 September – 3 October) so that each attacking division could be concentrated on a 1,000 yards (910 m) front. Roads and light railways were extended to the new front line, to allow artillery and ammunition to be moved forward. The artillery of VIII Corps and IX Corps on the southern flank, simulated preparations for attacks on Zandvoorde and Warneton. At 5.50 a.m. on 26 September, five layers of barrage fired by British artillery and machine-guns began. Dust and smoke thickened the morning mist and the infantry advanced using compass bearings.[108] Each of the three German ground-holding divisions attacked on 26 September, had an Eingreif division in support, twice the ratio of 20 September. No ground captured by the British was lost and German counter-attacks managed only to reach ground to which survivors of the front-line divisions had retired.[109]

Third phase: October–November

Battle of Broodseinde

The Battle of Broodseinde (4 October), was the last assault launched by Plumer in good weather.[110] The operation aimed to complete the capture of the Gheluvelt Plateau and occupy Broodseinde Ridge. The Germans sought to recapture their defences around Zonnebeke, with a methodical counter-attack also to begin on 4 October.[100] The British attacked along a 14,000 yards (13,000 m) front and by coincidence, Australian troops from I Anzac Corps met attacking troops from the German 45th Reserve Division in no man's land, when Operation Hohensturm commenced simultaneously.[111] The Germans had reinforced their front line to delay the British capture of their forward positions, until Eingreif divisions could intervene, which put more German troops into the area most vulnerable to British artillery.[112] The British inflicted devastating casualties on the 4th Army divisions opposite.[113]

German defensive changes

On 7 October, the 4th Army again dispersed its troops in the front defence zone. Reserve battalions moved back behind the artillery protective line and the Eingreif divisions were organised to intervene as swiftly as possible once an attack commenced, despite the risk of being devastated by the British artillery. Counter-battery fire to reduce British artillery fire was to be increased, to protect the Eingreif divisions as they advanced.[114] All of the German divisions holding front zones were relieved and an extra division brought forward, as the British advances had lengthened the front line. Without the forces necessary for a counter-offensive south of the Gheluvelt plateau towards Kemmel Hill, Rupprecht began to plan for a slow withdrawal from the Ypres salient, even at the risk of uncovering German positions further north and the Belgian coast.[115][lower-alpha 7]

Battle of Poelcappelle

The French First Army and British Second and Fifth armies attacked on 9 October, on a 13,500 yards (12,300 m) front, from south of Broodseinde to St. Jansbeek, to advance half of the distance from Broodseinde ridge to Passchendaele, on the main front, which led to many casualties on both sides. Advances in the north of the attack front were retained by British and French troops but most of the ground taken in front of Passchendaele and on the Becelaere and Gheluvelt spurs was lost to German counter-attacks.[116] General William Birdwood later wrote that the return of heavy rain and mud sloughs was the main cause of the failure to hold captured ground. Kuhl concluded that the fighting strained German fighting power to the limit but that the German forces managed to prevent a breakthrough, although it was becoming much harder to replace losses.[117]

First Battle of Passchendaele

The First Battle of Passchendaele on 12 October, was another Allied attempt to gain ground around Passchendaele. Heavy rain and mud again made movement difficult and little artillery could be brought closer to the front. Allied troops were exhausted and morale had fallen. After a modest British advance, German counter-attacks recovered most of the ground lost opposite Passchendaele.[118] There were 13,000 Allied casualties, including 2,735 New Zealanders, 845 of whom had been killed or lay wounded and stranded in the mud of no-man's-land. In lives lost in a day, this was the worst day in New Zealand history.[119] At a conference on 13 October, Haig and the army commanders agreed that attacks would stop until the weather improved and roads could be extended, to carry more artillery and ammunition forward for better fire support.[120]

Battle of La Malmaison

After numerous requests from Haig, Petain began the Battle of La Malmaison, a long-delayed French attack on the Chemin des Dames, by the Sixth Army (General Paul Maistre). The artillery preparation started on 17 October and on 23 October, the German defenders were swiftly defeated, losing 11,157 prisoners and 180 guns, as the French advanced up to 3.7 miles (6.0 km), capturing the village and fort of La Malmaison, gaining control of the Chemin des Dames ridge. The Germans had to withdraw to the north of the Ailette Valley early in November. Haig was pleased with the French success but regretted the delay, which had lessened its effect on the Flanders operations.[121]

Second Battle of Passchendaele

The British Fifth Army undertook minor operations from 20–22 October, to maintain pressure on the Germans and support the French attack at La Malmaison, while the Canadian Corps prepared for a series of attacks from 26 October – 10 November.[122][123] The four divisions of the Canadian Corps had been transferred to the Ypres Salient from Lens, to capture Passchendaele and the ridge.[124] The Canadians relieved the II Anzac Corps on 18 October and found that the front line was mostly the same as that occupied by the 1st Canadian Division in April 1915.[125] The Canadian operation was to be three limited attacks, on 26 October, 30 October and 6 November.[126] On 26 October, the 3rd Canadian Division captured its objective at Wolf Copse, then swung back its northern flank to link with the adjacent division of the Fifth Army. The 4th Canadian Division captured its objectives but was forced slowly to retire from Decline Copse, against German counter-attacks and communication failures between the Canadian and Australian units to the south.[127]

The second stage began on 30 October, to complete the previous stage and gain a base for the final assault on Passchendaele.[127] The attackers on the southern flank quickly captured Crest Farm and sent patrols beyond the final objective into Passchendaele. The attack on the northern flank again met with exceptional German resistance. The 3rd Canadian Division captured Vapour Farm on the corps boundary, Furst Farm to the west of Meetcheele and the crossroads at Meetcheele but remained short of its objective.[128] During a seven-day pause, the Second Army took over another section of the Fifth Army front adjoining the Canadian Corps.[129] Three rainless days from 3–5 November eased preparation for the next stage, which began on the morning of 6 November, with the 1st Canadian Division and the 2nd Canadian Division. In fewer than three hours, many units reached their final objectives and Passchendaele was captured. The Canadian Corps launched a final action on 10 November, to gain control of the remaining high ground north of the village near Hill 52, which ended the campaign apart from a night attack at Passchendaele on 1/2 December, an attack on the Polderhoek Spur on 2 December and some minor operations in the new year.[130][131][lower-alpha 8]

Aftermath

Analysis

| Date | Casualties | (Missing) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21–31 July | 30,000 | 9,000 | |

| 1–10 Aug | 16,000 | 2,000 | |

| 11–21 Aug | 24,000 | 5,000 | |

| 21–31 Aug | 12,500 | 1,000 | |

| 1–10 Sept | 4,000 | — | |

| 11–20 Sept | 25,000 | 6,500 | |

| 21–30 Sept | 13,500 | 3,500 | |

| 1–10 Oct | 35,000 | 13,000 | |

| 11–20 Oct | 12,000 | 2,000 | |

| 21–31 Oct | 20,500 | 3,000 | |

| 1–10 Nov | 9,500 | 3,000 | |

| 11–20 Nov | 4,000 | * | |

| 21–30 Nov | 4,500 | 500 | |

| 1–10 Dec | 4,000 | * | |

| 11–31 Dec | 2,500 | 500 | |

| Total | 217,000 | 49,000 | |

In a German General Staff publication, it was written that "Germany had been brought near to certain destruction (sicheren Untergang) by the Flanders battle of 1917".[133] In his Memoirs of 1938, Lloyd George wrote, "Passchendaele was indeed one of the greatest disasters of the war ... No soldier of any intelligence now defends this senseless campaign ...".[134] In 1939, G. C. Wynne wrote that the British had eventually reached Passchendaele Ridge and captured Flandern I Stellung; beyond them were Flandern II and Flandern III (which was nearly complete). The German submarine bases on the coast had not been captured but the objective of diverting the Germans from the French further south, while they recovered from the Nivelle Offensive of April, had succeeded.[135]

In 1997, Griffith wrote that the bite and hold system kept moving until November, because the BEF had developed a workable system of offensive tactics, against which the Germans ultimately had no answer.[136] A decade later, Sheldon wrote that relative casualty figures were irrelevant, because the German army could not afford great numbers of losses or to lose the initiative, by being compelled to fight another defensive battle on ground of the Allies' choosing. The Third Battle of Ypres pinned the German army to Flanders and caused unsustainable casualties.[137] At a conference on 13 October, a scheme of the Third Army for an attack in mid-November was discussed. Byng wanted the operations at Ypres to continue, to hold German troops in Flanders.[138] The Battle of Cambrai began on 20 November, when the British breached the first two parts of the Hindenburg Line, in the first successful mass use of tanks in a combined arms operation.[139]

The experience of the failure to contain the British attacks at Ypres and the drastic reduction in areas of the western front which could be considered "quiet", after the tank and artillery surprise at Cambrai, left the OHL with little choice but to return to a strategy of decisive victory in 1918.[140] On 24 October, the Austro-German 14th Army, under General der Infanterie Otto von Below, attacked the Italian Second Army on the Isonzo, at the Battle of Caporetto and in 18 days, inflicted casualties of 650,000 men and 3,000 guns.[141] In fear that Italy might be put out of the war, the French and British Governments offered reinforcements.[142] British and French troops were swiftly moved from 10 November – 12 December but the diversion of resources from the BEF forced Haig to conclude the 3rd Battle of Ypres short of Westrozebeke, the last substantial British attack being made on 10 November.[143]

Casualties

Various casualty figures have been published, sometimes with acrimony, although the highest estimates for British and German casualties appear to be discredited.[144] In the Official History, Brigadier-General J. E. Edmonds put British casualties at 244,897 and wrote that equivalent German figures were not available, estimating German losses at 400,000. Edmonds considered that 30 percent needed to be added to German statistics, to make them comparable with British casualty criteria.[145] In 2007, Sheldon wrote that although German casualties from 1 June – 10 November were 217,194, a figure available in Volume III of the Sanitätsbericht (1934), Edmonds may not have included them as they did not fit his case. Sheldon recorded 182,396 slightly wounded and sick soldiers not struck off unit strength, which if included would make 399,590 German losses.[146] The British claim to have taken 24,065 prisoners has not been disputed.[147][lower-alpha 10]

Commemoration

The Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing commemorates those of all Commonwealth nations, except New Zealand, who died in the Ypres Salient and have no known grave. In the case of the United Kingdom only casualties before 16 August 1917 are commemorated on the memorial. United Kingdom and New Zealand servicemen who died after that date are named on the memorial at Tyne Cot Cemetery. There are numerous tributes and memorials all over Australia and New Zealand to ANZAC soldiers who died in the battle, including plaques at the Christchurch and Dunedin railway stations. The Canadian Corps participation in the Second Battle of Passchendaele is commemorated with the Passchendaele Memorial located at the former site of the Crest Farm on the south-west fringe of Passchendaele village.[157] One of the newest monuments to be dedicated to the fighting contribution of a group is the Celtic Cross memorial, commemorating the Scottish contributions and efforts in the fighting in Flanders during the Great War. This memorial is located on the Frezenberg Ridge where the Scottish 9th and 15th Divisions, fought during the Battle of Passchendaele. The monument was dedicated by Linda Fabiani, the Minister for Europe of the Scottish Parliament, during the late summer of 2007, the 90th anniversary of the battle.[158]

See also

- Passchendaele - A Canadian film about the battle

Notes

- ↑ Passchendaele /ˈpæʃəndeɪl/ is the common English title. The British Battle Nomenclature Committee called the Flanders offensives of 1917, The Battle of Messines 1917 (7–14 June) and The Battles of Ypres 1917 (31 July – 10 November).[1]

- ↑ The series of battles are known to the British as The Battle of Messines 1917 (7–14 June), The Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July – 2 August), the Battle of Langemarck (16–18 August), The Battle of Menin Road Ridge (20–25 September), the Battle of Polygon Wood (26 September – 3 October) the Battle of Broodseinde (4 October), the Battle of Poelcappelle (9 October), the First Battle of Passchendaele (12 October) and the Second Battle of Passchendaele (26 October – 10 November) and referred to in German works as (Kampf um den Wijtschatebogen) (The Battle of the Wijtschate Salient) and the (Flandernschlacht) (Battle of Flanders) in five periods, First Battle of Flanders (31 July – 9 August), Second Battle of Flanders (9–25 August), Third Battle of Flanders (20 September – 8 October) Fourth Battle of Flanders (9–21 October) and Fifth Battle of Flanders (22 October – 5 December).[1][2]

- ↑ "High ground" is a relative term. Passchendaele is on a ridge about 70 feet (21 m) above the surrounding plains. The Gheluvelt plateau is about 100 feet (30 m) above surrounding area. Wytschaete is about 150 feet (46 m) above the ground before it; these terrain features were vital for artillery observation.[25]

- ↑ Brigadier-General John Charteris, Chief of British Army Intelligence in France, wrote in 1929 that "... in Flanders the weather broke early with the regularity of the Indian monsoon ...", a claim that has influenced several historians. The rest of the sentence is rarely quoted, "... once the autumn rains set in difficulties would be greatly enhanced". On the following page Charteris wrote, "Unfortunately there now set in the wettest August recorded for thirty years", which contradicted his first statement.[32] The Official Historian wrote that five times the average August rainfall in 1915 and 1916 fell in 1917.[33] Winter (1991) wrote that Haig had conclusive evidence that should have led him to expect heavy rainfall and hence mud.[34] Cruttwell (1940), Hart and Steel (2001) and Stevenson (2005), wrote that Haig was unlucky with the weather.[35][36][37] Sheffield (2011) wrote that the "predictable" rain in August "... has no foundation in fact. The rain in Flanders during the battle was abnormally heavy.", concurring with Terraine (1977).[38][39] In 1958, the former Lieutenant-Colonel Ernest Gold, Commandant of the Meteorological Section at GHQ in 1917, contradicted the first part of the passage in Charteris, "It is quite contrary to the evidence of the records which show that the weather in August 1917 was exceptionally bad ...".[40] Rainfall in August 1917 was 127 millimetres (5.0 in), of which 84 millimetres (3.3 in) fell on 1, 8, 14, 26 and 27 August, in a month so dull and windless, that the water on the ground dried unusually slowly. September had 40 millimetres (1.6 in) of rain and was much sunnier so the ground dried quickly, becoming hard enough in places for shells to ricochet and for dust to blow in the breeze. In October 1917, 107 millimetres (4.2 in) of rain fell, compared to the 1914–1916 average of 44 millimetres (1.7 in) and from 1–9 November there was 7.5 millimetres (0.30 in) of rain but only nine hours of sunshine, so little of the water dried; 13.4 millimetres (0.53 in) of rain fell on 10 November.[41]

- ↑ After mutinies in the French army, the British cabinet felt compelled to endorse the Passchaendale offensive, in the hope that more refusals to fight could be "averted by a great [military] success". Haig wrote that if the Allies could win the war in 1917, "the chief people to suffer would be the socialists".[50][51]

- ↑ The 4th Guards Division, 4th Bavarian Division, 6th Bavarian Division, 10th Ersatz Division, 16th Division, 19th Reserve Division, 20th Division, 187th Division, 195th Division and 45th Reserve Division took part in the battle.[98]

- ↑ 195th, 16th, 4th Bavarian, 18th, 227th, 240th, 187th and 22nd Reserve divisions).[98]

- ↑ German troops engaged were from the 239th, 39th, 4th, 44th Reserve, 7th, 11th, 11th Bavarian, 238th, 199th, 27th, 185th, 111th and 40th divisions.[98]

- ↑ German casualties were counted in ten-day periods. A discrepancy of 27,000 fewer casualties recorded in the Sanitätsbericht could not be explained by the Reichsarchiv historians. * Missing totals for 11–30 November and 1–31 December are combined[132]

- ↑ In 1940, C. R. M. F. Cruttwell recorded 300,000 British casualties and 400,000 German.[148] Wolff in 1958, gave German casualties as 270,713 and 448,688 British.[149] In 1959, Cyril Falls estimated 240,000 British, 8,525 French and 260,000 German casualties.[150] John Terraine followed Falls in 1963 but did not accept that German losses were as high as 400,000.[151] A. J. P. Taylor in 1972, wrote that the Official History had performed a "conjuring trick" on these figures and that no one believed these "farcical calculations". Taylor put British wounded and killed at 300,000 and German losses at 200,000.[152] In 1977, Terraine argued that twenty percent needed to be added to the German figures for some lightly wounded men, who would have been included under British definitions of casualties, making German casualties c. 260,400. Terraine refuted Wolff (1958), who despite writing that 448,614 British casualties was the total for the BEF in the second half of 1917, neglected to deduct 75,681 British casualties for the Battle of Cambrai given in the Official Statistics, from which he quoted or "normal wastage", averaging 35,000 per month in "quiet" periods.[153] Prior and Wilson in 1997, gave British losses as 275,000 and German casualties just under 200,000.[154] Hagenlücke in 1997, gave c. 217,000 German casualties.[72] Sheffield wrote in 2002, that Holmes's guess of 260,000 casualties on both sides seemed about right.[155] In 2011, Sheffield did not offer figures for either side, leaving the verdict to General von Kuhl, "The sacrifices that the British made for the Entente were fully justified".[156]

Footnotes

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, p. iii.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. xiv.

- ↑ Albertini 1952, p. 414.

- ↑ Albertini 1952, p. 504.

- ↑ Foley 2007, p. 102.

- ↑ Foley 2007, p. 104.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1932, p. 2.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p. 137.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 1.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 31.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Hart & Steel 2001, p. 30.

- ↑ Falls 1940, p. 21.

- ↑ Falls 1940, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1940, p. 14.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 31, 55, 94.

- ↑ Terraine 1999, p. 15.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 163–245.

- ↑ Falls 1940, pp. 533–534.

- 1 2 Terraine 1977, p. 278.

- ↑ Greenhalgh 2014, p. 215.

- ↑ Edmonds 1927, p. 353.

- ↑ Hart & Steel 2001, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 2.

- ↑ Hart & Steel 2001, p. 42.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, pp. 140–158.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, p. 141.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, p. 142.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 125.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Charteris 1929, pp. 272–273.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Winter 1991, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Cruttwell 1940, p. 440.

- ↑ Hart & Steel 2001, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Stevenson 2005, p. 335.

- ↑ Sheffield 2011, p. 233.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, pp. 149–151.

- ↑ Henniker 1937, p. 273.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 25.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 17–19.

- ↑ Powell 1993, p. 169.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 84.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 24.

- ↑ Sheffield 2011, pp. 227–231.

- ↑ Millman 2001, p. 61.

- ↑ French 1995, pp. 119–122, 92–93, 146.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 297–298.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 284.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 286–287.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. 1.

- ↑ Hart & Steel 2001, pp. 41–44.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ Hart & Steel 2001, p. 55.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. 28.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 87.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 234.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 290–297.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 127.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 126–127, 431–432.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 72–75.

- ↑ Davidson 1953, p. 29.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 440.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 89.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 90–95.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 185–187.

- 1 2 3 4 Liddle 1997, pp. 45–58.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 234.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 189–202.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 194.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 201.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 203.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 202–205.

- ↑ Simpson 2001, pp. 130–134.

- ↑ Rogers 2010, pp. 162–167.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 208.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp. 380–383.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 235.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 230.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 119–120.

- 1 2 Nicholson 1962, p. 308.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 237.

- 1 2 Marble 1998, App 22.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 236–242.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 257.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 303.

- ↑ Rogers 2010, p. 168.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. 184.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 307–308.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 307.

- 1 2 3 USWD 1920.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 184–186.

- 1 2 Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 135.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 238–239.

- ↑ Jones 1934, p. 181.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 261.

- ↑ Harris 2008, p. 366.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. 165.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 282–284.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 286–287.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 284.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 293.

- ↑ Robbins 2005, p. 128.

- ↑ Bean 1933, pp. 837, 847.

- ↑ Malkasian 2002, p. 42.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 316–317.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 309.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Bean 1933, p. 887.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 287–288.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 341–342.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, p. 285.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 345.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 307.

- ↑ Bean 1933, p. 930.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 347.

- ↑ Bean 1933, p. 929.

- ↑ Nicholson 1962, p. 312.

- ↑ Nicholson 1962, p. 314.

- 1 2 Nicholson 1962, p. 320.

- ↑ Nicholson 1962, p. 321.

- ↑ Nicholson 1962, p. 323.

- ↑ Nicholson 1962, p. 325.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 311–312.

- 1 2 Reichsarchiv 1942, p. 96.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. xiii.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. xix–xx.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, p. 71.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 313–317.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 345–346.

- ↑ Harris 1995, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Sheldon 2009, p. 312.

- ↑ Miles 1948, p. 15.

- ↑ Bean 1933, pp. 935–936.

- ↑ Bean 1933, p. 936.

- ↑ McRandle & Quirk 2006, pp. 667–701.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 361–363.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 313–315.

- ↑ Boraston 1919, p. 133.

- ↑ Cruttwell 1940, p. 442.

- ↑ Wolff 1958, p. 259.

- ↑ Falls 1959, p. 303.

- ↑ Terraine 1963, p. 372.

- ↑ Taylor 1972, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 344–345.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 195.

- ↑ Sheffield 2001, p. 216.

- ↑ Sheffield 2011, pp. 248 & 439.

- ↑ Vance 1997, p. 66.

- ↑ SG 2007.

References

- Books

- Albertini, L. (2005) [1952]. The Origins of the War of 1914. III (repr. ed.). New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 1-929631-33-2.

- Bean, C. E. W. (1941) [1933]. The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. IV (11th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 0-7022-1710-7.

- Boraston, J. H. (1920) [1919]. Sir Douglas Haig's Despatches (repr. ed.). London: Dent. OCLC 633614212.

- Charteris, J. (1929). Field Marshal Earl Haig. London: Cassell. ISBN 1-135-10031-4.

- Cruttwell, C. R. M. F. (1982) [1940]. A History of the Great War 1914–1918 (repr. ed.). London: Granada. ISBN 0-586-08398-7.

- Davidson, Sir J. (2010) [1953]. Haig: Master of the Field (Pen & Sword ed.). London: Peter Nevill. ISBN 1-84884-362-3.

- Die Kriegführung im Sommer und Herbst 1917. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Militärischen Operationen zu Lande. XIII. pub. 1956 (Die digitale landesbibliotek Oberösterreich ed.). Berlin: Mittler. 2012 [1942]. OCLC 257129831. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MS: Belknap Harvard. ISBN 0-674-01880-X.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1995) [1927]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1915: Winter 1915: Battle of Neuve Chapelle: Battle of Ypres. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-218-7.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-185-7.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (2010) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: Appendices. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 1-84574-733-X.

- Falls, C. (1992) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-180-6.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-166-0.

- Falls, C. (1959). The Great War 1914–1918. London: Perigee. ISBN 0-399-50100-2.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916 (pbk. ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- French, D. (1995). The Strategy of the Lloyd George Coalition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198205597.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2014). The French Army and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60568-8.

- Harris, J. P. (1995). Men, Ideas and Tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903–1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4814-1.

- Harris, J. P. (2008). Douglas Haig and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Hart, P.; Steel, N. (2001). Passchendaele: the Sacrificial Ground. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35975-0.

- Henniker, A. M. (2009) [1937]. Transportation on the Western Front 1914–1918. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-765-7.

- Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-One Divisions of the German Army which Participated in the War (1914–1918) (PDF). Washington D.C.: United States Army, American Expeditionary Forces, Intelligence Section. 1920. ISBN 5-87296-917-1. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1934]. The War in the Air Being the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. IV (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-415-0.

- Liddle, P. H. (1997). Passchendaele in Perspective: The Third Battle of Ypres. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 0-85052-588-8.

- Malkasian, C. (2002). A History of Modern Wars of Attrition. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-97379-4.

- Miles, W. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: The Battle of Cambrai. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. III (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-162-8.

- Millman, B. (2001). Pessimism and British War Policy, 1916–1918. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 071465079X.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1962). Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationary. OCLC 557523890. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- Powell, G. (2004) [1993]. Plumer: The Soldier's General (Leo Cooper ed.). Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 1-84415-039-9.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (1996). Passchendaele: The Untold Story. Cumberland: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07227-9.

- Robbins, S. (2005). British Generalship on the Western Front 1914–18: Defeat into Victory. Abingdon: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-415-35006-9.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Sheffield, G. (2002) [2001]. Forgotten Victory: The First World War: Myths and Realities (reprint ed.). London: Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 0-7472-7157-7.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.

- Sheldon, J. (2007). The German Army at Passchendaele. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 1-84415-564-1.

- Sheldon, J. (2009). The German Army at Cambrai. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-944-4.

- Simpson, A. (2005) [2001]. The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (Spellmount ed.). London: London University. ISBN 1-86227-292-1.

- Stevenson, D. (2005). 1914–1918 The History of the First World War. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-026817-0.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1972). The First World War. An Illustrated History. New York: Perigee Trade. ISBN 0-399-50260-2.

- Terraine, J. (1977). The Road to Passchendaele: The Flanders Offensive 1917, A Study in Inevitability. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-436-51732-9.

- Terraine, J. (1999). Business in Great Waters. Ware: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-84022-201-8.

- Terraine, J. (1963). Douglas Haig: The Educated Soldier (2005 ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35319-1.

- Vance, J. F. (1997). Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning and the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 0-7748-0600-1.

- Winter, D. (1992) [1991]. Haig's Command: A Reassessment (Penguin ed.). New York: Viking. ISBN 0-14-007144-X.

- Wolff, L. (1958). In Flanders Fields: The 1917 Campaign. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-14-014662-2.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, Westport, CT ed.). Cambridge: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-8371-5029-9.

- Journals

- McRandle, J. H.; Quirk, J. (3 July 2006). "The Blood Test Revisited: A New Look at German Casualty Counts in World War I". 70. Lexington, VA: The Journal of Military History: 667–701. ISSN 0899-3718.

- Theses

- Marble, S. (2003) [1998]. The Infantry Cannot do with a Gun Less: The Place of the Artillery in the BEF, 1914–1918 (PhD). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-50219-2. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Websites

- "Tribute to Scots Soldiers at Passchendaele". The Scottish Government. 24 August 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

Further reading

- Davies, C. B.; Edmonds, J. E.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1995) [1937]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1918: March – April: Continuation of the German Offensives. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-223-3.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1993) [1947]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1918: 26th September–11th November The Advance to Victory. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. V (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-192-X.

- Kershaw, I. (2000) [1999]. Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris (reprint ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-04671-0.

- Perry, R. A. (2014). To Play a Giant's Part: The Role of the British Army at Passchendaele. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-78331-146-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Third Battle of Ypres. |

- Third Ypres, Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- Passchendaele – Canada's Other Vimy Ridge, Norman Leach, Canadian Military Journal

- Passchendaele Memorial Plate New Zealand History Online

- Passchendaele, original reports from The Times

- Battles: The Third Battle of Ypres, 1917

- Westhoek The great war in Flanders Fields – A war and peace experience

- Second Lieutenant Robert Riddel, Military Cross, 10th Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, Passchendaele, 12 October 1917

- Guernsey students re-trace a soldier's journey to Passchendaele, for Radiowaves (2007)

- Passchendaele – The Final Call – James Willard

- Uncovering the secrets of Ypres, Robert Hall, 23 February 2007. BBC News, Belgium

- The Battle of Passchendaele. Day by day description of battle (with maps)

- Canadian movie of the battle

- Historical film documents on the Battles of Ypres at www.europeanfilmgateway.eu