Prehistoric Britain

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the British Isles |

|

| Prehistoric period |

| Classical period |

| Medieval period |

| Early modern period |

| Late modern period |

| By region |

|

|

| Periods in English history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For the purposes of this article, Prehistoric Britain is Britain during the period between the first arrival of humans on the land mass now known as Great Britain and the start of recorded British history.[1] The "recorded history" of Britain is conventionally reckoned to begin in AD 43 with the Roman invasion of Britain, though some historical information is available from before then.

Archaeological prehistory, which comprises the bulk of this article, is commonly divided into distinct chronological periods. These are based on the development of tools, from stone to bronze and iron, as well as changes in culture and climate that can be determined from the archaeological record. The boundaries of these periods are uncertain, as the changes between them are gradual. In addition, the dates of these changes demonstrated in Britain are generally different from those of Continental Europe.

Context

Britain has been intermittently inhabited by members of the Homo genus for hundreds of thousands of years, and by Homo sapiens for tens of thousands of years. Modern humans reached Britain by around 42,000 years before present (BP),[2] but the island was unoccupied during the last glacial maximum, between about 25,000 and 15,000 years ago.[3]

People then briefly re-occupied Britain, but cold conditions returned during the Younger Dryas, about 12,900 to 11,600 years ago. It is not known whether Britain was wholly uninhabited during the Younger Dryas, but people certainly moved in when the climate improved around 9600 BC. Britain and Ireland were then joined to the Continent, but rising sea levels cut the land bridge between Britain and Ireland by around 11,000 years ago. A large plain between Britain to Continental Europe, known as Doggerland, persisted much longer, probably until around 5600 BC.[4]

By around 4000 BC, the island was populated by people with a Neolithic culture.[5] However, none of the pre-Roman inhabitants of Britain had any known, surviving, written language. Because no literature of pre-Roman Britain has survived, its history, culture and way of life are known mainly through archaeological finds. Though the main evidence for the period is archaeological, there is a growing amount of genetic evidence, which continues to change. There is also a small amount of linguistic evidence, from river and hill names, which is covered in the article about Pre-Celtic Britain and the Celtic invasion.

The first significant written record of Britain and its inhabitants was made by the Greek navigator Pytheas, who explored the coastal region of Britain around 325 BC. However, there may be some additional information on Britain in the "Ora Maritima", a text which is now lost but which is incorporated in the writing of the later author Avienus. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that ancient Britons were involved in extensive maritime trade and cultural links with the rest of Europe from the Neolithic onwards, especially by exporting tin that was in abundant supply. Julius Caesar also wrote of Britain in about 50 BC after his two military expeditions to the island in 55 and 54 BC. The 54 invasion was probably an attempt to conquer at least the southeast of Britain but failed.[6]

Located at the fringes of Europe, Britain received European technological and cultural achievements much later than Southern Europe and the Mediterranean region did during prehistory. The story of ancient Britain is traditionally seen as one of successive waves of invasion from the continent, with them coming different cultures and technologies. More recent archaeological theories have questioned this migrationist interpretation and argue for a more complex relationship between Britain and the Continent.[7] Many of the changes in British society demonstrated in the archaeological record are now suggested to be the effects of the native inhabitants adopting foreign customs rather than being subsumed by an invading population.

Stone Age

Palaeolithic

Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) Britain is the period of the earliest known occupation of Britain by humans. This huge period saw many changes in the environment, encompassing several glacial and interglacial episodes greatly affecting human settlement in the region. Providing dating for this distant period is difficult and contentious. The inhabitants of the region at this time were bands of hunter-gatherers who roamed Northern Europe following herds of animals, or who supported themselves by fishing.

Recent (2006) scientific evidence[8] regarding mitochondrial DNA sequences from ancient and modern Europe has shown a distinct pattern for the different time periods sampled in the course of the study. Despite some limitations regarding sample sizes, the results were found to be non-random. As such, the results indicate that, in addition to populations in Europe expanding from southern refugia after the last glacial maximum (especially the Franco-Cantabrian region), evidence also exists for various northern refugia.

Lower and Middle Palaeolithic

(From about 800,000 to 45,000 years ago)

There is evidence from bones and flint tools found in coastal deposits near Happisburgh in Norfolk and Pakefield in Suffolk that a species of Homo was present in what is now Britain at least 814,000 years ago. At this time, Southern and Eastern Britain were linked to continental Europe by a wide land bridge (Doggerland) allowing humans to move freely. The current position of the English Channel was a large river flowing westwards and fed by tributaries that later became the Thames and Seine. Reconstructing this ancient environment has provided clues to the route first visitors took to arrive at what was then a peninsula of the Eurasian continent. Archaeologists have found a string of early sites located close to the route of a now lost watercourse named the Bytham River which indicate that it was exploited as the earliest route west into Britain.

Sites such as Boxgrove in Sussex illustrate the later arrival in the archaeological record of an archaic Homo species called Homo heidelbergensis around 500,000 years ago. These early peoples made Acheulean flint tools (hand axes) and hunted the large native mammals of the period. One hypothesis is that they drove elephants, rhinoceroses and hippopotamuses over the tops of cliffs or into bogs to more easily kill them.

The extreme cold of the following Anglian Stage is likely to have driven humans out of Britain altogether and the region does not appear to have been occupied again until the ice receded during the Hoxnian Stage. This warmer time period lasted from around 424,000 until 374,000 years ago and saw the Clactonian flint tool industry develop at sites such as Swanscombe in Kent. The period has produced a rich and widespread distribution of sites by Palaeolithic standards, although uncertainty over the relationship between the Clactonian and Acheulean industries is still unresolved.

Britain was only populated intermittently, and even during periods of occupation may have reproduced below replacement level and needed immigration from elsewhere to maintain numbers. According to Paul Pettitt and Mark White:

- The British Lower Palaeolithic (and equally that of much of northern Europe) is thus a long record of abandonment and colonisation, and a very short record of residency. The sad but inevitable conclusion of this must be that Britain has little role to play in any understanding of long-term human evolution and its cultural history is largely a broken record dependent on external introductions and insular developments that ultimately lead nowhere. Britain, therefore, was an island of the living dead.[9]

This period also saw Levallois flint tools introduced, possibly by humans arriving from Africa. However, finds from Swanscombe and Botany Pit in Purfleet support Levallois technology being a European rather than African introduction. The more advanced flint technology permitted more efficient hunting and therefore made Britain a more worthwhile place to remain until the following period of cooling known as the Wolstonian Stage, 352,000–130,000 years ago. Britain first became an island about 350,000 years ago.[10] Early Neanderthal remains discovered at the Pontnewydd Cave in Wales have been dated to 230,000 BP,[11] and are the most north westerly Neanderthal remains found anywhere in the world.

From c.180,000 to c.60,000 years ago there is no evidence of human occupation in Britain, probably due to inhospitable cold in some periods, Britain being cut off as an island in others, and the neighbouring areas of north-west Europe being unoccupied by hominins at times when Britain was both accessible and hospitable.[12]

Upper Palaeolithic

(around 45,000 – 10,000 years ago)

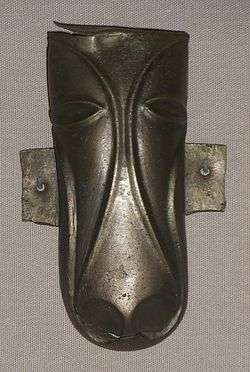

This period is often divided into three subperiods: the Early Upper Palaeolithic (before the main glacial period), the Middle Upper Palaeolithic (the main glacial period) and the Late Upper Palaeolithic (after the main glacial period). There was limited Neanderthal occupation of Britain in Marine Isotope Stage 3 between about 60,000 and 42,000 years BP. Britain had its own unique variety of late Neanderthal handaxe, the bout-coupé, so seasonal migration between Britain and the continent is unlikely, but the main occupation may have been in the now submerged area of Doggerland, with summer migrations to Britain in warmer periods.[13] La Cotte de St Brelade in Jersey is the only site in the British Isles to have produced late Neanderthal fossils.[14]

The earliest evidence for modern humans in North West Europe is a jawbone discovered in England at Kents Cavern in 1927, which was re-dated in 2011 to between 41,000 and 44,000 years old.[15][16] The most famous example from this period is the burial of the "Red Lady of Paviland" (actually now known to be a man) in modern-day coastal South Wales, which in 1823 was the first human fossil ever discovered anywhere in the world, and was re-dated in 2009 to 33,000 years old. The distribution of finds shows that humans in this period preferred the uplands of Wales and northern and western England to the flatter areas of eastern England. Their stone tools are similar to those of the same age found in Belgium and far north-east France, and very different from those in north-west France. At a time when Britain was not an island, hunter gatherers may have followed migrating herds of reindeer from Belgium and north-east France across the giant Channel River.[17]

The climatic deterioration which culminated in the Last Glacial Maximum, between about 26,500 and 19,000–20,000 years ago,[18] drove humans out of Britain, and there is no evidence of occupation for around 18,000 years after c.33,000 years BP.[19] Sites such as Cathole Cave in Swansea County dated at 14,500BP,[20] Creswell Crags in Nottinghamshire at 12,800BP and Gough's Cave in Somerset 12,000 years BP, provide evidence suggesting that humans returned to Britain towards the end of this ice age during a warm period from 14,700 to 12,900 years BP ago (the Bølling-Allerød interstadial known as the Windermere Interstadial in Britain), although further extremes of cold right before the final thaw may have caused them to leave again and then return repeatedly. The environment during this ice age period would have been a largely treeless tundra, eventually replaced by a gradually warmer climate, perhaps reaching 17 degrees Celsius (62.6 Fahrenheit) in summer, encouraging the expansion of birch trees as well as shrub and grasses.

The first distinct culture of the Upper Palaeolithic in Britain is what archaeologists call the Creswellian industry, with leaf-shaped points probably used as arrowheads. It produced more refined flint tools but also made use of bone, antler, shell, amber, animal teeth, and mammoth ivory. These were fashioned into tools but also jewellery and rods of uncertain purpose. Flint seems to have been brought into areas with limited local resources; the stone tools found in the caves of Devon, such as Kent's Cavern, seem to have been sourced from Salisbury Plain, 100 miles (161 km) east. This is interpreted as meaning that the early inhabitants of Britain were highly mobile, roaming over wide distances and carrying 'toolkits' of flint blades with them rather than heavy, unworked flint nodules, or else improvising tools extemporaneously. The possibility that groups also travelled to meet and exchange goods or sent out dedicated expeditions to source flint has also been suggested.

The dominant food species were equines (Equus ferus) and Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), although other mammals ranging from hares to mammoth were also hunted, including rhino and hyena. From the limited evidence available, burial seemed to involve skinning and dismembering a corpse with the bones placed in caves. This suggests a practice of excarnation and secondary burial, and possibly some form of ritual cannibalism. Artistic expression seems to have been mostly limited to engraved bone, although the cave art at Creswell Crags and Mendip caves are notable exceptions.

Between about 12,890 and 11,650 years ago Britain returned to glacial conditions during the Younger Dryas, and may have been unoccupied for periods.[21]

Mesolithic

(around 10,000 to 5,500 years ago)

The Younger Dryas ended around 11,500 years BP (about 9500 BC)[22] and the Holocene, a geological epoch, began (at 11,700 calendar years BP),[23] and continues to the present. By 8000 BC temperatures were higher than today, and birch woodlands spread rapidly.[24] The plains of Doggerland were thought to have finally been submerged around 6500 to 6000 BC,[25] but recent evidence suggests that the bridge may have lasted until between 5800 and 5400 BC, and possibly as late as 3800 BC.[26] The warmer climate changed the arctic environment to one of pine, birch and alder forest; this less open landscape was less conducive to the large herds of reindeer and wild horse that had previously sustained humans. Those animals were replaced in people's diets by pig and less social animals such as elk, red deer, roe deer, wild boar and aurochs (wild cattle), which would have required different hunting techniques. Tools changed to incorporate barbs which could snag the flesh of an animal, making it harder for it to escape alive. Tiny microliths were developed for hafting onto harpoons and spears. Woodworking tools such as adzes appear in the archaeological record, although some flint blade types remained similar to their Palaeolithic predecessors. The dog was domesticated because of its benefits during hunting, and the wetland environments created by the warmer weather would have been a rich source of fish and game. It is likely that these environmental changes were accompanied by social changes. Humans spread and reached the far north of Scotland during this period. Sites from the British Mesolithic include the Mendips, Star Carr in Yorkshire and Oronsay in the Inner Hebrides. Excavations at Howick in Northumberland uncovered evidence of a large circular building dating to c. 7600 BC which is interpreted as a dwelling. A further example has also been identified at Deepcar in Sheffield, and a building dating to c. 8500 BC was discovered at the Star Carr site. The older view of Mesolithic Britons as nomadic is now being replaced with a more complex picture of seasonal occupation or, in some cases, permanent occupation. Travel distances seem to have become shorter, typically with movement between high and low ground.

Wheat of a variety grown in the middle East was present on the Isle of Wight at the Bouldnor Cliff Mesolithic Village dating from about 8,000 BP.[27]

Mesolithic-Neolithic transition

Though the Mesolithic environment was of a bounteous nature, the rising population and the ancient Britons' success in exploiting it eventually led to local exhaustion of many natural resources. The remains of a Mesolithic elk found caught in a bog at Poulton-le-Fylde in Lancashire show that it had been wounded by hunters and escaped on three occasions, indicating hunting during the Mesolithic. A few Neolithic monuments overlie Mesolithic sites but little continuity can be demonstrated. Farming of crops and domestic animals was adopted in Britain around 4500 BC, at least partly because of the need for reliable food sources. Hunter-gathering ways of life would have persisted into the Neolithic at first but the increasing sophistication of material culture with the concomitant control of local resources by individual groups would have caused it to be replaced by distinct territories occupied by different tribes. Other elements of the Neolithic such as pottery, leaf-shaped arrowheads and polished stone axes would have been adopted earlier. The climate had been warming since the later Mesolithic and continued to improve, replacing the earlier pine forests with woodland.

In 1997, DNA analysis was carried out on a tooth from a Mesolithic Cheddar Man from about 7150 BC whose remains were found in Gough's Cave at Cheddar Gorge. His mitochondrial DNA was of Haplogroup U5, a subclade of Haplogroup U (mtDNA) found in only 11% of modern European populations, suggesting he (and maybe his clan) had migrated to Britain from outside of Europe. Haplogroup U was the dominant type of Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in Europe before the spread of agriculture into Europe.[28]

Neolithic

(from around 4300 – 2000 BC)

The Neolithic was the period of domestication of plants and animals.

Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA of modern European populations shows that over 80% are descended in the female line from European hunter-gatherers. Less than 20% are descended in the female line from Neolithic farmers from the Middle East and from subsequent migrations. The percentage in Britain is smaller at around 11%. Initial studies suggested that this situation is different with the paternal Y-chromosome DNA, varying from 10–100% across the country, being higher in the east. This was considered to show a large degree of population replacement during the Anglo-Saxon invasion and a nearly complete masking over of whatever population movement (or lack of it) went before in these two countries.[29] However, more widespread studies have suggested that there was less of a division between Western and Eastern parts of Britain with less Anglo-Saxon migration.[30] Looking from a more Europe-wide standpoint, researchers at Stanford University have found overlapping cultural and genetic evidence that supports the theory that migration was at least partially responsible for the Neolithic Revolution in Northern Europe (including Britain).[31] The science of genetic anthropology is changing very fast and a clear picture across the whole of human occupation of Britain has yet to emerge.[32]

Pollen analysis shows that woodland was decreasing and grassland increasing, with a major decline of elms. The winters were typically 3 degrees colder than at present but the summers some 2.5 degrees warmer.

The arrival of farming and a sedentary lifestyle as shorthand for the Neolithic is increasingly giving way to a more complex view of the changes and continuities in practices that can be observed from the Mesolithic period onwards. For example, the development of Neolithic monumental architecture, apparently venerating the dead, may represent more comprehensive social and ideological changes involving new interpretations of time, ancestry, community and identity.

In any case, the Neolithic Revolution, as it is called, introduced a more settled way of life and ultimately led to societies becoming divided into differing groups of farmers, artisans and leaders. Forest clearances were undertaken to provide room for cereal cultivation and animal herds. Native cattle and pigs were reared whilst sheep and goats were later introduced from the continent, as were the wheats and barleys grown in Britain. However, only a few actual settlement sites are known in Britain, unlike the continent. Cave occupation was common at this time.

The construction of the earliest earthwork sites in Britain began during the early Neolithic (c. 4400 BC – 3300 BC) in the form of long barrows used for communal burial and the first causewayed enclosures, sites which have parallels on the continent. The former may be derived from the long house, although no long house villages have been found in Britain — only individual examples. The stone-built houses on Orkney — such as those at Skara Brae — are, however, indicators of some nucleated settlement in Britain. Evidence of growing mastery over the environment is embodied in the Sweet Track, a wooden trackway built to cross the marshes of the Somerset Levels and dated to 3807 BC. Leaf-shaped arrowheads, round-based pottery types and the beginnings of polished axe production are common indicators of the period. Evidence of the use of cow's milk comes from analysis of pottery contents found beside the Sweet Track.

The Middle Neolithic (c. 3300 BC – c. 2900 BC) saw the development of cursus monuments close to earlier barrows and the growth and abandonment of causewayed enclosures, as well as the building of impressive chamber tombs such as the Maeshowe types. The earliest stone circles and individual burials also appear.

Different pottery types, such as Grooved ware, appear during the later Neolithic (c. 2900 BC – c. 2200 BC). In addition, new enclosures called henges were built, along with stone rows and the famous sites of Stonehenge, Avebury and Silbury Hill, which building reached its peak at this time. Industrial flint mining begins, such as that at Cissbury and Grimes Graves, along with evidence of long distance trade. Wooden tools and bowls were common, and bows were also constructed.

Bronze Age

(around 2200 to 750 BC)

This period can be sub-divided into an earlier phase (2300 to 1200 BC) and a later one (1200 – 700 BC). Beaker pottery appears in England around 2475–2315 cal. BC[33] along with flat axes and burial practices of inhumation. With the revised Stonehenge chronology, this is after the Sarsen Circle and trilithons were erected at Stonehenge. Believed to be of Iberian origin (modern day Spain and Portugal), Beaker techniques brought to Britain the skill of refining metal. At first the users made items from copper, but from around 2,150 BC smiths had discovered how to smelt bronze (which is much harder than copper) by mixing copper with a small amount of tin. With this discovery, the Bronze Age arrived in Britain. Over the next thousand years, bronze gradually replaced stone as the main material for tool and weapon making.

Britain had large, easily accessible reserves of tin in the modern areas of Cornwall and Devon in what is now Southwest England, and thus tin mining began. By around 1600 BC the Southwest of Britain was experiencing a trade boom as British tin was exported across Europe, evidence of ports being found in Southern Devon at Bantham and Mount Batten. Copper was mined at the Great Orme in North Wales.

The Beaker people were also skilled at making ornaments from gold, silver and copper, and examples of these have been found in graves of the wealthy Wessex culture of Central Southern Britain.

Early Bronze Age Britons buried their dead beneath earth mounds known as barrows, often with a beaker alongside the body. Later in the period, cremation was adopted as a burial practice with cemeteries of urns containing cremated individuals appearing in the archaeological record, with deposition of metal objects such as daggers. People of this period were also largely responsible for building many famous prehistoric sites such as the later phases of Stonehenge along with Seahenge. The Bronze Age people lived in round houses and divided up the landscape. Stone rows are to be seen on, for example, Dartmoor. They ate cattle, sheep, pigs and deer as well as shellfish and birds. They carried out salt manufacture. The wetlands were a source of wildfowl and reeds. There was ritual deposition of offerings in the wetlands and in holes in the ground. There was some debate amongst archaeologists as to whether the "Beaker people" were a race of people who migrated to Britain en masse from the continent, or whether a prestigious Beaker cultural "package" of goods and behaviour (which eventually spread across most of Western Europe) diffused to Britain's existing inhabitants through trade across tribal boundaries. Modern thinking tends towards the latter view. Alternatively, a ruling class of Beaker individuals may have made the migration and come to control the native population at some level. Genetics suggests that there was only a small influx of people to Britain at this time, around a few percent.

There is evidence of a relatively large scale disruption of cultural patterns which some scholars think may indicate an invasion (or at least a migration) into Southern Great Britain c. the 12th century BC. This disruption was felt far beyond Britain, even beyond Europe, as most of the great Near Eastern empires collapsed (or experienced severe difficulties) and the Sea Peoples harried the entire Mediterranean basin around this time. Some scholars consider that the Celtic languages arrived in Britain at this time,[34][35][36][37][38][39] but the more generally accepted view is that Celtic origins lie with the Hallstatt culture.

The Iron Age

(around 750 BC – 43 AD)

In around 750 BC iron working techniques reached Britain from Southern Europe. Iron was stronger and more plentiful than bronze, and its introduction marks the beginning of the Iron Age. Iron working revolutionised many aspects of life, most importantly agriculture. Iron tipped ploughs could churn up land far more quickly and deeply than older wooden or bronze ones, and iron axes could clear forest land far more efficiently for agriculture. There was a landscape of arable, pasture and managed woodland. There were many enclosed settlements and land ownership was important.

It is generally thought that by 500 BC most people inhabiting the British Isles were speaking Common Brythonic, on the limited evidence of place-names recorded by Pytheas of Massalia and transmitted to us second-hand, largely through Strabo. Certainly by the Roman period there is substantial place- and personal name evidence which suggests that this was so; Tacitus also states in his Agricola that the British language differed little from that of the Gauls.[40] Among these people were skilled craftsmen who had begun producing intricately patterned gold jewellery, in addition to tools and weapons of both bronze and iron. It is disputed whether Iron Age Britons were "Celts", with some academics such as John Collis[41] and Simon James[42] actively opposing the idea of 'Celtic Britain', since the term was only applied at this time to a tribe in Gaul. However, placenames and tribal names from the later part of the period suggest that a Celtic language was spoken. The traveller Pytheas, whose own works are lost, was quoted by later classical authors as calling the people "Pretanoi", which is cognate with "Britanni" and is apparently Celtic in origin. The term "Celtic" continues to be used by linguists to describe the family that includes many of the ancient languages of Western Europe and modern British languages such as Welsh without controversy.[43] The dispute essentially revolves around how the word "Celtic" is defined; it is clear from the archaeological and historical record that Iron Age Britain did have much in common with Iron Age Gaul, but there were also many differences. Many leading academics, such as Barry Cunliffe, still use the term to refer to the pre-Roman inhabitants of Britain for want of a better label.

Iron Age Britons lived in organised tribal groups, ruled by a chieftain. As people became more numerous, wars broke out between opposing tribes. This was traditionally interpreted as the reason for the building of hill forts, although the siting of some earthworks on the sides of hills undermined their defensive value, hence "hill forts" may represent increasing communal areas or even 'Elite Areas'. However some hillside constructions may simply have been cow enclosures. Although the first had been built about 1500 BC, hillfort building peaked during the later Iron Age. There are over 2000 Iron Age hillforts known in Britain.[44] By about 350 BC many hillforts went out of use and the remaining ones were reinforced. Pytheas was quoted as writing that the Britons were renowned wheat farmers. Large farmsteads produced food in industrial quantities and Roman sources note that Britain exported hunting dogs, animal skins and slaves.

The Late pre-Roman Iron Age (LPRIA)

The last centuries before the Roman invasion saw an influx of mixed Germanic-Celtic speaking refugees from Gaul (approximately modern day France and Belgium) known as the Belgae, who were displaced as the Roman Empire expanded around 50 BC. They settled along most of the coastline of Southern Britain between about 200 BC and AD 43, although it is hard to estimate what proportion of the population there they formed. A Gaulish tribe known as the Parisi, who had cultural links to the continent, appeared in Northeast England.

From around 175 BC, the areas of Kent, Hertfordshire and Essex developed especially advanced pottery-making skills. The tribes of Southeast England became partially Romanised and were responsible for creating the first settlements (oppida) large enough to be called towns.

The last centuries before the Roman invasion saw increasing sophistication in British life. About 100 BC, iron bars began to be used as currency, while internal trade and trade with continental Europe flourished, largely due to Britain's extensive mineral reserves. Coinage was developed, based on continental types but bearing the names of local chieftains. This was used in Southeast England, but not in areas such as Dumnonia in the west.

As the Roman Empire expanded northwards, Rome began to take interest in Britain. This may have been caused by an influx of refugees from Roman occupied Europe, or Britain's large mineral reserves. See Roman Britain for the history of this subsequent period.

See also

- Timeline of prehistoric Britain

- Prehistoric settlement of the British Isles

- Boxgrove

- Gough's Cave

- Genetic history of the British Isles

- Happisburgh

- Happisburgh footprints

- Kents Cavern

- List of human evolution fossils

- List of prehistoric structures in Great Britain

- Pakefield

- Paviland

- Pontnewydd

- Swanscombe

- Arras Culture

- Wetwang Slack

- Danes Graves

Notes

- ↑ The time prior to the arrival of the genus Homo is also "prehistoric" Britain, hence the initial qualification.

- ↑ Higham, T.; et al. (24 November 2011). "The earliest evidence for anatomically modern humans in northwestern Europe". Nature. Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 479 (7374): 521–524. doi:10.1038/nature10484. PMID 22048314.

- ↑ Cunliffe, 2012, p. 47

- ↑ Cunliffe, 2012, pp. 47-56

- ↑ Prehistoric Britain 6000BC – 55BC, Guide to Britain Archived 11 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Webster, Graham (1980). The Roman Invasion of Britain. Batsford. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7134-1329-8.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry. "Britain, the Veneti and beyond. 1982". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 1 (1): 39–68. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1982.tb00298.x. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Molecular Biology and Evolution 2006 23(1):152–161 Tracing the Phylogeography of Human Populations in Britain Based on 4th–11th Century mtDNA Genotypes (full text]

- ↑ Pettitt and White, pp. 132-33

- ↑ Phil Gibbard, How Britain Became An Island: The report, Nature Precedings doi:10.1038/npre.2007.1205.1

- ↑ "The oldest people in Wales – Neanderthal teeth from Pontnewydd Cave". National Museum of Wales. 2007.

- ↑ Pettitt and White, p. 292

- ↑ Pettitt and White, pp. 332, 349-51

- ↑ Bates, Martin; Pope, Matthew; Shaw, Andrew; Scott, Beccy; Schwenninger, Jean-Luc (16 October 2013). "Late Neanderthal occupation in North-West Europe: rediscovery, investigation and dating of a last glacial sediment sequence at the site of La Cotte de Saint Brelade, Jersey". Journal of Quaternary Science. 28: 647–652. doi:10.1002/jqs.2669.

- ↑ Higham, T; Compton, T; Stringer, C; Jacobi, R; Shapiro, B; Trinkaus, E; Chandler, B; Groening, F; Collins, C; Hillson, S; O'Higgins, P; FitzGerald, C; Fagan, M (2011), "The earliest evidence for anatomically modern humans in northwestern Europe", Nature, 479: 521–524, doi:10.1038/nature10484, PMID 22048314

- ↑ "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". The New York Times. 2 November 2011.

- ↑ Dinnis, Robert (Winter 2012). "Hunting the Hunter". The British Museum Magazine (74): 26.

- ↑ Clark, Peter U.; Dyke, Arthur S.; Shakun, Jeremy D.; Carlson, Anders E.; Clark, Jorie; Wohlfarth, Barbara; Mitrovica, Jerry X.; Hostetler, Steven W. & McCabe, A. Marshall (2009). "The Last Glacial Maximum". Science. 325 (5941): 710–4. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..710C. doi:10.1126/science.1172873. PMID 19661421.

- ↑ Pettitt and White, p. 422

- ↑ U-series dating suggests Welsh reindeer is Britain’s oldest rock art, http://www.bris.ac.uk/news/2012/8606.html

- ↑ Pettitt and White, pp. 489, 497

- ↑ Muscheler, Raimund; et al. (2008). "Tree rings and ice cores reveal 14C calibration uncertainties during the Younger Dryas". Nature Geoscience. 1 (4): 263–267. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..263M. doi:10.1038/ngeo128.

- ↑ Walker, M., Johnsen, S., Rasmussen, S. O., Popp, T., Steffensen, J.-P., Gibbard, P., Hoek, W., Lowe, J., Andrews, J., Bjo¨ rck, S., Cwynar, L. C., Hughen, K., Kershaw, P., Kromer, B., Litt, T., Lowe, D. J., Nakagawa, T., Newnham, R., and Schwander, J. 2009. Formal definition and dating of the GSSP (Global Stratotype Section and Point) for the base of the Holocene using the Greenland NGRIP ice core, and selected auxiliary records. J. Quaternary Sci., Vol. 24 pp. 3–17. ISSN 0267-8179.

- ↑ Cunliffe, 2012, p. 58

- ↑ McIntosh, Jane Handbook of Prehistoric Europe Oxford University Press, USA (Jun 2009) ISBN 978-0-19-538476-5 p.24

- ↑ Cunliffe, 2012, p. 56

- ↑ Balter, Michael. "DNA recovered from underwater British site may rewrite history of farming in Europe.". Science. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ , A Revised Timescale for Human Evolution Based on Ancient Mitochondrial Genomes, Fu et al. 2013

- ↑ Molecular Biology and Evolution 19: 1008–1021 (full text)

- ↑ Stephen Openheimer, The Origins of the British

- ↑ Overlapping Genetic and Archaeological Evidence Suggests Neolithic Migration, Say Stanford Researchers (2002) (press release)

- ↑ European Journal of Human Genetics (2005) 13, 1293–1302 (full text)

- ↑ Pearson, Mike; Julian Thomas (September 2007). "The Age of Stonehenge". Antiquity. 811 (313): 617–639.

- ↑ http://www.aber.ac.uk/aberonline/en/archive/2008/05/au7608/

- ↑ "O'Donnell Lecture 2008 Appendix" (PDF).

- ↑ Koch, John (2009). Tartessian: Celtic from the Southwest at the Dawn of History in Acta Palaeohispanica X Palaeohispanica 9 (2009) (PDF). Palaeohispanica. pp. 339–351. ISSN 1578-5386. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ↑ Koch, John. "New research suggests Welsh Celtic roots lie in Spain and Portugal". Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Karl, Guerra, McEvoy, Bradley; Oppenheimer, Rrvik, Isaac, Parsons, Koch, Freeman and Wodtko (2010). Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Oxbow Books and Celtic Studies Publications. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ↑ "Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe" (PDF). University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies and Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ The Agricola, Tacitus.

- ↑ Collis, John. The Celts – Origins, Myths and Inventions. Tempus, 2003

- ↑ James. Simon. The Atlantic Celts British Museum Press, 1999

- ↑ Ball, Martin J. & James Fife (ed.) (1993). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-01035-7.

- ↑ The Iron Age, smr.herefordshire.gov.uk

Sources

- Ball, Martin J. & James Fife (ed.). 1993. The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-01035-7.

- British History Encyclopedia. 1999. Paragon House. ISBN 1-4054-1632-7.

- Collis, John. 2003. The Celts – Origins, Myths and Inventions. Tempus.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2012). Britain Begins. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967945-4.

- James, Simon. 1999. The Atlantic Celts. British Museum Press.

- Pearson, Mike; Cleal, Ros; Marshall, Peter; Needham, Stuart; Pollard, Josh; Richards, Colin; Ruggles, Clive; Sheridan, Alison; Thomas, Julian; et al. (2007). "The Age of Stonehenge". Antiquity. 811 (313): 617–639.

- Pettitt, Paul; White, Mark (2012). The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-67455-3.

Further reading

- Alonso, Santos, Carlos Flores, Vicente Cabrera, Antonio Alonso, Pablo Martín, Cristina Albarrán, Neskuts Izagirre, Concepción de la Rúa and Oscar García. 2005. The place of the Basques in the European Y-chromosome diversity landscape. European Journal of Human Genetics 13:1293-1302.

- Ashton, Nick. 2003. "Hunting for the first humans in Britain", British Archaeology, Iss 70, May 2003

- Cunliffe, Barry 2001. Facing the Ocean: The Atlantic and Its Peoples, 8000 BC to AD 1500. Oxford University Press.

- Cunliffe, Barry. 2002. The Extraordinary Voyage of Pytheas the Greek. Penguin.

- Darvill, Timothy C. 1987. Prehistoric Britain. London: B.T. Batsford ISBN 0-7134-5179-3

- Hawkes, Jaquetta and Christopher. 1943. Prehistoric Britain. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Miles, David. 2016. "The Tale of the Axe: How the Neolithic Revolution Transformed Britain". London. Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05186-3

- Oppenheimer, Stephen. 2006. The Origins of the British. London: Constable.

- Pryor, Francis. 1999. Farmers in Prehistoric Britain. Stroud, Gloucestershire and Charleston, SC: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1477-1

- Pryor, Francis. 2003. Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland before the Romans. London, Harper-Collins. ISBN 0-00-712692-1

- Sykes, Brian. 2001. The Seven Daughters of Eve: The Science That Reveals Our Genetic Ancestry. Bantam, London. ISBN 0-593-04757-5

- Sykes, Brian. 2006. Saxons, Vikings, and Celts: The Genetic Roots of Britain and Ireland. New York, Norton & Co. (Published in the UK, also in 2006, as Blood of the Isles. London, Bantam Books.)

- Wainright, Richard. 1978. A Guide to Prehistoric Remains in Britain. London: Constable.

- Weale, Michael E.; Weiss, Deborah A.; Jager, Rolf F.; Bradman, Neil; Thomas, Mark G. (2002). "Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (7): 1008–1021. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004160. PMID 12082121.

External links

- Ancient Human Occupation of Britain Project

- Britain's human history revealed

- 700,000-year-old remains in Norfolk

- The Boxgrove project

- Ancient Britons come mainly from Spain

- An audio-visual presentation by Dr Mike Weale of UCL talking about genetic evidence for migration