Hawker Sea Hawk

| Sea Hawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sea Hawk in livery of the Fleet Air Arm | |

| Role | Naval fighter |

| Manufacturer | Hawker Aircraft Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft |

| Designer | Sydney Camm |

| First flight | 2 September 1947 |

| Introduction | March 1953 |

| Retired | 1983 |

| Primary users | Royal Navy German Navy Royal Netherlands Navy Indian Navy |

| Number built | 542 |

| Variants | Hawker P.1072 |

The Hawker Sea Hawk was a British single-seat jet fighter of the Fleet Air Arm (FAA), the air branch of the Royal Navy (RN), built by Hawker Aircraft and its sister company, Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft. Although its origins stemmed from earlier Hawker piston-engined fighters, the Sea Hawk became the company's first jet aircraft.

Following the type's acceptance in the RN, the Sea Hawk proved to be a reliable and sturdy workhorse. A considerable number were also produced for the export market, and were operated from aircraft carriers in both Dutch and Indian service. The last operational Sea Hawks, operated by the Indian Navy, were retired in 1983.

Design and development

Origins

In the final years of the Second World War, Hawker's design team had become increasingly interested in developing a fighter aircraft that took advantage of the newly developed jet propulsion technology. Prior to this, Hawker had been heavily committed until late 1944 to the production and further development of its existing piston-powered aircraft, such as the Hurricane, Tempest and Typhoon, to meet the wartime demands for these aircraft. On 1 September 1944, the first prototype of the company's latest fighter aircraft, the Hawker Fury/Sea Fury, conducted its maiden flight; it was this aircraft that would serve as the fundamental design basis for Hawker's first jet-powered aircraft.[1]

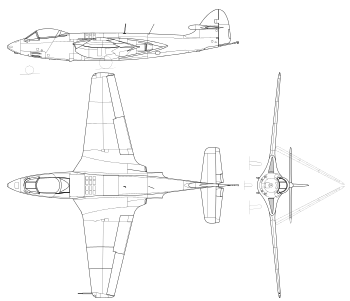

Initially, the design team studied the potential adaption of the existing aircraft, having opted to use the Rolls-Royce Griffon-powered Fury prototype as the starting point.[1] First and foremost, the team started with the deletion of the piston engine, with its replacement, a single Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet engine, being fitted in a mid-fuselage position, along with lateral air intakes and a tailpipe which emerged beneath the tailplane.[1] The prospective modifications also included "stretching" the fuselage and moving the cockpit to the extreme front of the fuselage in a re-contoured nose; this design received the internal designation P.1035. Use of the Rolls-Royce Derwent engine had been studied but quickly discarded as being incapable of generating sufficient thrust for an aircraft of this size.[1] In November 1944 the P.1035 design was submitted for evaluation by the Air Ministry.[1]

In December 1944 Hawker refined the proposed design substantially, the jet exhausts being re-designed to use short split-lateral bifurcated exhausts (which gained the name "trouser legs"), which were moved from beneath the tail and embedded in the trailing edge of the wing root, accompanied by a corresponding thickening of the wing root; the air intakes also moved, to the forward wing root area, similar to the contemporary de Havilland Vampire.[1] The unusual bifurcated jet pipe reduced jet pipe power loss and had the additional advantage of freeing up space in the rear fuselage for fuel tanks, which thus led to the aircraft possessing a longer range than many other early jets.[2] The absence of fuel tanks also meant a thinner wing could be adopted without the penalty of reduced range; to ease manufacture, the elliptical wingform of the Fury was discarded in favour of a straight tapered wing design.[1] The fuselage fuel tanks, being fore and aft of the engine, also provided for a stable centre of gravity during flight. The tail plane was raised in order to clear the jet exhausts.[1][2] The Sea Hawk also featured a nosewheel undercarriage arrangement, the first for a Hawker-built aircraft.[1] The aircraft was built to accommodate four 20mm Hispano-Suiza Mk. V cannons.

The redesign had led to a new designation for the project, P.1040, being applied.[2][1] The Air Ministry quickly issued its encouragement for Hawker's development of the project, however, according to aviation author Francis K. Mason, both the Air Ministry and the Admiralty had initially viewed the project with only academic interest.[3] Official interest had also been cooled by the expression of doubts voiced by Rolls-Royce Limited on the viability of the bifurcated jet pipes that the design used.[4] Like the piston-powered Fury it had been initially derived from, Hawker remained keen to promote the P.1040 to both the RAF and to the Navy.[1] Initially, the P.1040 was intended for the interceptor role, even though a top speed of only 600 mph was forecast.[5] Shortly following the aftermath of the war, the Royal Air Force (RAF) decided to not only cancel several large orders for Hawker's piston-powered aircraft, but to also announce that the service would be taking no further interest in the P.1040 proposals.[4]

As such, Hawker elected to refine the P.1040 design while it remained as a private venture, albeit being prepared with a view for service with British military customers in mind.[2] In October 1945,[6] Sydney Camm, Hawker's chief designer, being satisfied with the results generated from engineering mock-ups and wind tunnel testing, authorised the raising of a production order for a single prototype by the company's experimental department.[4] In light of the diminished RAF interest in the project,[5] allegedly due to the aircraft offering insufficient advances over the jet fighters that were already in service, such as the Gloster Meteor and de Havilland Vampire; in January 1946, a navalised version of the P.1040 was offered by Hawker to the Admiralty as a fleet support fighter, designated as the P.1046.[7]

The Admiralty were not initially encouraging to Hawker's approaches, in part due the presence of the in-development jet-powered Supermarine Attacker aircraft.[4] However, the service was intrigued by the long-range capability of the P.1040, as well as by the promise of increased power from the Nene engine. Thus, in May 1946, the Naval Staff authorised the manufacture of three prototypes and a further test specimen, one of these being the original prototype internally ordered by Hawker, in accordance with Naval Specification N.7/46.[4] Hawker quickly found their development focus for the type being divided between the navy's P.1046 and the general-purpose P.1040, which was still hoped to be viable as an RAF fighter.[4] The P.1040 would lead to the eventual development of the land-based swept wing Hawker Hunter fighter. Swept wing versions (P.1052 and P.1081) were built and experience gained with these were instrumental in developing the design of the Hunter.[4]

Prototypes

On 2 September 1947, the P.1040 prototype, VP401, sometimes referred to as the Hawker N.7/46 after the related naval specification, conducted its maiden flight from RAF Boscome Down, piloted by Bill Humble.[7] Three days later, VP401 flew to Farnborough to continue trials.[8] A month after the first flight, the existence of the P.1040 was revealed to the general public.[9] Early flight trials encountered aerodynamic-related teething problems, such as airframe vibrations and tail buffeting, and thus led to a redesign of the rear jetpipe fairings and the addition of a bullet fairing on the tail to correct these issues.[9] Other minor issues were addressed, including high stick forces and windshield distortion; VP401 was limited to performing long takeoff run, which was attributed to the low-powered Nene 1, at that point, the engine had been yet not rated for its full power settings.[10]

On 31 August 1948, a fully navalised prototype, VP413, which was equipped with folding wings, catapult spools and a full armament, conducted its first flight. VP413 was quickly subjected to a series of deck assessment trials using a mockup deck at Boscombe Down.[9] In April 1949, VP413 was transferred to the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious to conduct general deck and handling trials at sea. These trials revealed the need for the wing span to be increased by 30 inches, the low-speed handling of the prototype having been found to be lacking.[9] In November 1949, VP413 was re-deployed to Illustrious, performing around 25 deck landings without issue.[9]

On 17 October 1949, the third prototype, VP422, made its maiden flight.[9] Being representative of the subsequent production aircraft, VP422 incorporated a number of modifications as a result of the experiences gained from trials with the second prototype, these alterations included the fitting of a longer arrester hook when a number of "bolters" were experienced during the early dummy deck trials.[9] After the longer hook was incorporated, this modification was carried though the remaining production runs.[11] Other changes included the addition of fixtures for rocket-assisted take-off gear (RATOG) and hard points plumbed for external drop tanks. On 22 November 1949, Hawker received an initial production contract for 151 aircraft, the aircraft also received the name Sea Hawk at this point.[9] Throughout 1950, both VP413 and VP422 were used to conduct preliminary service trials.[9]

VP422, the third prototype, later joined a specially prepared Vampire Mk 21 in testing the feasibility of operating without an undercarriage utilizing a flexible deck. Flying from Farnborough, VP413 successfully completed both catapult launches and "rubber sheet" deck landings, with the undercarriage remaining retracted throughout the flights. Although the system was proved, the project was abandoned in 1950 when the introduction of more powerful engines had effectively precluded the need to radically adapt the design to the concept of combat aircraft without undercarriages.[12]

VP401, the first prototype, had continued to serve in the flight test programme and was involved in two significant events prior to its retirement. On 1 August 1949, the Royal Navy entered VP401 in the National Air Races, in which it won the Society of British Aircraft Constructors (SBAC) Challenge Cup Race, beating out both a Vampire 3 and de Havilland DH.108. VP401 was later converted into a further prototype, the Hawker P.1072, the principal addition being in the form of an auxiliary rocket engine; configured as such, it became the first British rocket-powered aircraft.[13] After a few flights were made in 1950, the rocket engine blew up during a test and although repaired, the airframe was scrapped soon after.[12]

Production

Immediately following the receipt of the first order in November 1949, Hawker set about establishing a manufacturing line for the Sea Hawk at their Kingston facility.[9] Shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War, an urgent operational demand for Britain's aircraft carriers, and thus their accompanying aircraft, had become apparent. The rate of production was substantially increased, and further orders for the Sea Hawk were soon placed.[14] The issuing of a 'Super-Priority' status for the Sea Hawk by Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1951, served to speed up production considerably as well as aid the supply of vital materials for its manufacture.[15]

Under such demands for the aircraft, in order that production shortcomings could be better addressed, along with the parallel pressure that Hawker was facing on the development of another aircraft, the newer Hunter, it was decided that production would be transferred to a new assembly line ran by Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft, which were a part of the Hawker group, at Coventry.[15] Prior to the transfer, a total of 35 Sea Hawk F1, the initial production standard, were completed at Kingston.[15] On 14 November 1951, the first production Sea Hawk F1, WF143, conducted its maiden flight.[15] It possessed a 39 ft (12 m) wingspan and a tailplane of increased area. The first Coventry-built Sea Hawk F1 made its first flight prior to the end of 1953; a total of 60 would be produced.[15]

While some of the initial batch of Sea Hawks would see operational service, many of the F1 aircraft would be mostly used for various service trials.[15] Amongst these, WF143 would later be rebuilt as the prototype for the Sea Hawk F2, featuring power-assisted ailerons in place of their unpowered counterparts on the F1, to which flight trials had demonstrated a weakness in lateral control leading to instances of oscillation.[15] On 24 February 1954, the first production Sea Hawk F2, WF240, conducted its maiden flight at Bitteswell. A total of 40 F2 aircraft would be produced.[15]

Another Sea Hawk F1, WF157, was developed into a prototype for the FB 3 standard, the initial fighter bomber variant of the type and later most common of the Sea Hawk variants.[15] In order to suit this role, much of the development work went into its range of external stores, although the clearance of these for service was disrupted by a lack of available Royal Navy personnel.[16] On 13 March 1954, the first production Sea Hawk FB 3, WF280, made its first flight.[15] A more refined Sea Hawk FGA 4 variant followed, partially to address stores handling issues that had been experienced with the FB 3 variant; the first FB 4 aircraft, WV792 conducted its first flight on 26 August 1954.[17]

In 1950, it was acknowledged that the Nene 101 engine was transitional powerplant; upon availability of the 4 per cent more powerful Nine 103, the Admiralty quickly ordered that many of its Sea Hawk FB 3 and FGA 4 be re-engined.[17] Accordingly, another two Sea Hawk variants were developed; the first of these, the FB 5, was more or less identical to the FB 3, differing by being re-engined with the newer, more powerful Nene 103 engine, which greatly improving the aircraft's low-speed handling and take-off performance. The final Sea Hawk standard, FGA 6, was a fighter ground-attack variant; it was exactly the same as its FB 5 predecessor, though they were new-build aircraft rather than re-engined ones. A total of just under 90 FGA 6s were completed.[18]

Design

The F 1 was armed with four 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano Mk V cannons. It was powered by a single 5,000 lbf (22 kN) thrust Rolls-Royce Nene 101 centrifugal-equipped turbojet engine. The Nene engine was viewed as being a major shortcoming on the aircraft due to its lack of power; in 1950, the government had cancelled development of the Rolls-Royce Tay, an afterburner-equipped further development of the Nene engine, leaving no more powerful engines to equip the Sea Hawk.[17] More minor developments of the Nene engine were developed and were adopted on the aircraft, providing for some increase in power.[17]

The F 1 had a maximum speed of 599 mph (964 km/h) at sea level and a range of 800 mi (1,287 km) on internal fuel. A more refined fighter variant was the F 2, which introduced power-boosted aileron controls as well as other modifications, including to its structure.[19] The next variant of the Sea Hawk was developed into a fighter-bomber, the FB 3, and differed only slightly from its predecessors; its structure being strengthened to allow it to carry a wider array of equipment and weaponry on its four hard points, these included rockets, bombs, napalm, mines, reconnaissance cameras, external drop tanks and fixtures for rocket-assisted take-off gear (RATOG).[16]

Unlike its rival, the Supermarine Attacker, which had been the first jet aircraft to enter service with the FAA, the Sea Hawk had a tricycle undercarriage rather than a tail-wheel, making it easier to land on carriers, it was also Hawker's first aircraft to incorporate a nose-wheel undercarriage.[1] The Sea Hawk had adopted a fairly conventional design, being built with straight wings while a number of other contemporary aircraft, such as the F-86 Sabre, had adopted swept wings. The Sea Hawk was a reliable and elegant aeroplane, though its cautious design meant it would only be attractive on the export market, and thus be in production, for only a short period before being superseded by more advanced aircraft.

Operational history

_Suez_1956.jpg)

The first production Sea Hawk was the F 1, which first flew in 1951, entered service two years later with 806 Squadron, first based at Brawdy, then transferred to the HMS Eagle.[20][15] All Sea Hawks were in service by the mid-1950s and eventually over 500 were built.[18]

During service evaluations of the Sea Hawk, both Australian and Canadian pilots from each of their respective naval services would fly examples of the aircraft, and there were official suggestions they would adopt the type as standard equipment.[21] However, both nations were also interested in new American-built naval aircraft; only a handful of Sea Hawks would be transferred to either nation, notably some would operate from the flight deck of the Australian Majestic class aircraft carrier HMS Sydney, though these did not enter full squadron service.[22]

In 1956, shortly after the termination of the Sea Hawk production line, the Federal Republic of Germany placed an order for 64 aircraft to equip the German Bundesmarine, the Navy of West Germany, having determined the type to represent good value for money.[22] Requiring both fair-weather daytime fighter bombers and day time fighters with a bad weather flight capability, these were delivered in two separate variants. The first of these German export variants, for the fair-weather role, was designated as the Sea Hawk Mk 100, while the bad-weather capable model was designated as the Sea Hawk Mk 101; 32 aircraft of each variant were ordered. The Mk 101 was equipped with a pod-based EKCO-built search radar for sea reconnaissance.[22] The German Sea Hawks served into the mid-1960s, until its replacement by the F-104 Starfighter.[18]

The Netherlands also placed an order for 30 aircraft, designated as the Sea Hawk Mk 50, a ground-attack variant for the Royal Netherlands Navy, which was financed under NATO-issued funding.[22] The Mk 30 was externally similar to the Royal Navy's own aircraft, differing in its use of a Philips-built ultra high frequency (UHF) radio; Dutch Sea Hawks were also later equipped to each carry a pair of AIM-9 Sidewinder infrared-guided air-to-air missiles..[22] Between 1957 and 1964, the Dutch Navy operated a total of 22 aircraft.[23] The last export customer was India who ordered a mix of 24 new-build Sea Hawks and 12 refurbished ex-FAA Mk 6s in 1959, following up with 30 additional airframes reconstructed from West German stocks, among others.[23]

Combat record

The Sea Hawk, as part of the Fleet Air Arm, saw extensive service during the Suez Crisis, initiated by Egypt's nationalisation of the Suez Canal and naval blockade of southern Israeli ports in violation of the 1949 armistice and UN Security Council resolution denying passage of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. The United Kingdom, France and Israel conspired to provoke war, with the Anglo-French invasion being known as Operation Musketeer, beginning on 31 October 1956.[24] During the conflict, six Sea Hawk squadrons took part: two were aboard the fleet carrier HMS Eagle and two each aboard the light fleet carriers HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark. The Sea Hawks were primarily used to perform ground attack missions in the theatre, due to aircraft such as the Hunter lacking the range or clearance to deliver munitions, the entire British ground attack capability during the conflict was delivered by the Royal Navy's Sea Hawks, typically being escorted by de Havilland Sea Venom fighters.[25]

Sea Hawks launched many attacks upon Egyptian shore-based targets, often in the face of heavy anti-aircraft fire, resulting in several aircraft being severely damaged.[25] The military conduct of the Suez Campaign was successful, unlike the political disaster, and all invasion forces were withdrawn by 1957, though the waterway was reopened to Israeli ships.[24] The Suez Crisis was to be the key note of Sea Hawk combat operations with the Royal Navy, as a new generation of strike aircraft were introduced in the aftermath of the conflict, namely the de Havilland Sea Vixen and the Supermarine Scimitar.[25]

The Sea Hawk was a successful export aircraft. In the Royal Netherlands Navy, it served aboard the Dutch aircraft carrier HNLMS Karel Doorman, ex-HMS Venerable, including decolonization operations guarding against Indonesian threats in the area. From 1959 they were equipped with Sidewinder missiles significantly enhancing and extending their air-to-air combat capabilities.[26] In 1961, the Sea Hawks that served on her were moved ashore when the NATO mission profile was changed to all ASW aircraft; by October 1964 they had been taken out of service.

In Indian Navy service (beginning in 1960), Sea Hawks were used aboard the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant, ex-HMS Hercules and saw service during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. The latter war saw Sea Hawks being used by the Indian Navy; these aircraft scored nearly a dozen "kills", mainly of Pakistan Navy gunboats and Merchant navy ships and cargo ships in East Pakistan (present day Bangladesh) without losing an aircraft in the war.[27] Aided by Breguet Alize aircraft, the Sea Hawks emerged unscathed, achieving the highest kill ratio for any aircraft in the war. The Sea Hawk was withdrawn from Indian Navy service in 1983, being replaced by the far more capable BAE Sea Harrier.

Retirement

The Sea Hawks in Fleet Air Arm service began being phased out from first line service in 1958, the year in which the Supermarine Scimitar and de Havilland Sea Vixen entered service, both of which types would eventually replace the Sea Hawk. The last front line Sea Hawk squadron, No. 806, disbanded at RNAS Brawdy on 15 December 1960, ending a very brief operational career for the Sea Hawk. Most Sea Hawks in second line service were withdrawn by the mid-1960s. The last operational Royal Navy Sea Hawks were FGA.6 flown by the Airwork Limited managed "black" Fleet Requirements Unit based at Bournemouth (Hurn) Airport which retired the type in 1969.[28]

Variants

- P.1040

- VP401 prototype first flown at Boscombe Down on 2 September 1947, later converted to a P.1072

- VP413 navalised prototype to specification N.7/46 first flown at Farnborough 3 September 1948.

- VP422 second-naval prototype first flown at Farnborough 17 October 1949.

- Sea Hawk F1

- Production fighters powered by a Rolls-Royce Nene Mk 101 engine; 95 built (35 by Hawker Aircraft at Kingston upon Thames, the remainder and all subsequent production by Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft at Baginton, Coventry)

- Sea Hawk F2

- Production fighter with powered ailerons; 40 built by Armstrong Whitworth.

- Sea Hawk FB 3

- Fighter-bomber variant with stronger wing for external stores; 116 built.

- Sea Hawk FGA 4

- Fighter/Ground attack variant; 97 built.

- Sea Hawk FB 5

- FB3 fitted with the Nene Mk 103; 50 conversions.

- Sea Hawk FGA 6

- FGA4 with the Nene Mk 103; total of 101 (86 new-build, the remainder converted from FB3 and FGA 4 examples).

- Sea Hawk Mk 50

- Export variant based on the FGA 6 for the Royal Netherland Navy; 22 built.

- Sea Hawk Mk 100

- Export variant for the West German Navy, similar to FGA 6 but fitted with taller fin and rudder; 32 built

- Sea Hawk Mk 101

- All-weather export variant for the West German Navy, as Mk 100 but fitted with a search radar in an underwing pod; 32 built.

Operators

Surviving aircraft

.jpg)

.jpg)

36 complete Sea Hawks (plus eight cockpit sections) are known to survive as of 2011, mainly in a variety of locations in the United Kingdom, though others are located abroad, including in Germany, Malta, the Netherlands and India. One Sea Hawk, WV908, remains airworthy as part of the Royal Navy Historic Flight in the UK, although refurbishing the aircraft including fitting a Nene 103 took place in 2009.[29]

- WF219 (Sea Hawk F 1) is stored at the Fleet Air Arm Museum, Yeovilton, England.

- WF225 (Sea Hawk F 1) is displayed as 'gate guardian' at RNAS Culdrose (HMS Seahawk), England.[30]

- WF259 (Sea Hawk F 2) is stored at the National Museum of Flight, East Fortune, Scotland.[31]

- WM913 (Sea Hawk FB 5) is displayed at the Newark Air Museum, Newark, England.[32]

- WM961 (Sea Hawk FB 5) is displayed at Caernarfon Air World, Caernarfon, Wales.[33]

- WM969 (Sea Hawk FB 5) is displayed in Hangar 3 at the Imperial War Museum, Duxford, England.[34]

- WN108 (Sea Hawk FB 5) is displayed by the Ulster Aviation Society at Long Kesh, Northern Ireland.[35]

- WV797 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is displayed at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England.[36]

- WV798 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) (displayed until late 2009 at Lasham, England), 2009-2013 stored with Parkhouse Aviation at Booker, England. 2013 obtained by Classic Air Force, Newquay, England. Currently undergoing full restoration.

- WV826 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is displayed at the Malta Aviation Museum, Ta'qali, Malta.[37]

- WV856 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is displayed at Fleet Air Arm Museum, Yeovilton, England.[38]

- WV865 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is displayed at the Luftwaffe Museum, Gatow, Germany.

- WV908 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is airworthy with the Royal Navy Historic Flight, Yeovilton, England.[39]

- XE327 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is displayed at Hermeskeil, Germany.[40]

- XE340 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) (displayed until recently at the Montrose Air Station Museum, Scotland) returned to the FAA Museum, Yeovilton.

- XE489 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is displayed at the Gatwick Aviation Museum, Charlwood, England.[41]

- XE368 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) At the docks on Barrow Island, England.[42]

- 118 (Sea Hawk Mk 50) is displayed at De Kooy, Netherlands.

- 131 (Sea Hawk Mk 50) is displayed at Kamp Zeist, Militaire Luchtvaart Museum(MLM) Netherlands.

- MS+001 (Sea Hawk Mk 100) is displayed at Internationales Luftfahrt-Museum, Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany.

- IN-174 (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is displayed at Jawahar Bal Bhavan, Museum Road, Trivandrum, Kerala, India.[43]

- IN-240 Sea Hawk is displayed at the Victory at Sea Memorial, Beach Road, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India.[44]

- "Unknown Serial" (Sea Hawk FGA 6) is displayed in the Aeronautical Engineering Dept at IIT Madras.[45]

Specifications (Sea Hawk FGA 6)

Data from The Sea Hawk ...Epitome of Elegance,[46] The Hawker Sea Hawk[47]

General characteristics

- Crew: One

- Length: 39 ft 8 in (12.09 m)

- Wingspan: 39 ft 0 in (11.89 m)

- Height: 8 ft 8 in (2.64 m)

- Wing area: 278 ft² (25.83 m²)

- Empty weight: 9,278 lb (4,208 kg)

- Loaded weight: 13,220 lb (5,996 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 16,150 lb (7,325 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Rolls-Royce Nene 103 turbojet, 5,200 lbf (23.1 kN)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 600 mph (965 km/h)

- Range: 480 mi (770 km)

- Service ceiling: 44,500 ft (13,564 m)

- Rate of climb: 5,700 ft/min (29.0 m/s)

- Wing loading: 48 lb/ft² (232 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.38

Armament

- Guns: 4 × 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano Mk V cannons (200 rpg)

- Hardpoints: 6 underwing and provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: 20 × "60 lb" (27 kg) unguided rockets or 16 × 5 in (127 mm) unguided rockets

- Bombs: 4 × 500 lb (227 kg) bombs

- Other: or 2 × 90 Imp gal (410 l) drop tanks

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- de Havilland Vampire

- F-84 Thunderjet

- F2H Banshee

- F9F Panther

- Gloster Meteor

- MiG-15

- MiG-17

- Supermarine Attacker

- Dassault Ouragan

- North American FJ-1 Fury

- North American FJ-2/-3 Fury

- Related lists

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Mason 1966, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 Badrocke 2002. p. 60.

- ↑ Mason 1966, pp. 3-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mason 1966, p. 4.

- 1 2 Mason 1991, p. 316.

- ↑ Buttler (2004), p. 204.

- 1 2 James 2002, p. 48.

- ↑ Mason 1966, pp. 4-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mason 1966, p. 5.

- ↑ James 2002, pp. 48, 50.

- ↑ James 2002, p. 50.

- 1 2 James 2002, p. 55.

- ↑ "Rocket Motor Doubles Power of Jet Aircraft." Popular Mechanics, February 1952, p. 116.

- ↑ Mason 1966, pp. 5-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Mason 1966, p. 6.

- 1 2 Mason 1966, pp. 6-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Mason 1966, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Green 1982, p. 49.

- ↑ Brown 1982, p. 289.

- ↑ Brown 1982, p. 287.

- ↑ Mason 1966, pp. 8-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mason 1966, p. 9.

- 1 2 James 1982, p. 66.

- 1 2 "Establishment of UNEF." United Nations, Retrieved: 14 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Mason 1966, p. 8.

- ↑ Rickard, J (6 June 2010), Hawker Sea Hawk Mark 50, http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/weapons_hawker_sea_hawk_50.html

- ↑ Harry, B. "Damage Assessment - 1971 Indo-Pak Naval War v.2.0." orbat.com, 1 February 2005. Retrieved: 22 July 2009.

- ↑ James 1982, p. 62.

- ↑ "We're Still Here! Summer Update." royalnavyhistoricflight.org.uk, Royal Navy Historic Flight, 25 June 2009. Retrieved: 22 July 2009.

- ↑ http://www.thunder-and-lightnings.co.uk/seahawk/survivor.php?id=62

- ↑ http://www.nms.ac.uk/national-museum-of-flight/discover-the-museum/aircraft-location/

- ↑ http://www.newarkairmuseum.org/aircraft-list

- ↑ http://www.thunder-and-lightnings.co.uk/seahawk/survivor.php?id=175

- ↑ http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/70000193

- ↑ http://www.ulsteraviationsociety.org/sea-hawk/4537302632

- ↑ http://www.midlandairmuseum.co.uk/aircraftlist.php

- ↑ http://www.maltaaviationmuseum.com/#!hawker-sea-hawk-fga-6-wv826/c2qe

- ↑ http://www.fleetairarm.com/exhibit/hawker-sea-hawk/3-5-28.aspx

- ↑ http://www.royalnavyhistoricflight.org.uk/aircraft/seahawk.htm

- ↑ http://www.flugausstellung.de/flugzeuge.html

- ↑ http://www.gatwick-aviation-museum.co.uk/seahawk/seahawk.html

- ↑ http://www.thunder-and-lightnings.co.uk/seahawk/survivor.php?id=257

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.warbirdsofindia.com/ap/9-coastal/30-hawker-sea-hawk-in240.html

- ↑ http://www.warbirdsofindia.com/tamilnadu/chennai/mit/115-sea-hawk-in252.html

- ↑ Brown 2002, p. 285.

- ↑ Mason 1966, p. 12.

- Bibliography

- Badrocke, Mike. "Hawker's First Jet: Database, Hawker Sea Hawk." Aeroplane, September 2002.

- Brown, Eric, Captain. "The Sea Hawk ...Epitome of Elegance." Air International, Volume 23, no. 6, December 1982.

- Buttler, Tony. Hawker Sea Hawk (Warpaint No.29). Denbigh East, Bletchley, UK: Hall Park, 2001. ISSN 1363-0369.

- Buttler, Tony (2004). British Secret Projects. Midland Publishing. pp. 203–205. ISBN 1-85780-179-2.

- Green, William, ed. "Hawker Sea Hawk": Fighter A-Z." Air International, Volume 23, no. 1, July 1982.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Hannah, Donald. Hawker FlyPast Reference Library. Stamford, Lincolnshire, UK: Key Publishing Ltd., 1982. ISBN 0-946219-01-X.

- James, Derek N. Hawker, an Aircraft Album No.5. New York: Arco Publishing Company, 1973. ISBN 0-668-02699-5. (First published in the UK by Ian Allan in 1972)

- James, Derek N. "Type History: Database, Hawker Sea Hawk." Aeroplane, September 2002.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Fighter since 1912. London: Putnam, 1979. ISBN 0-85177-852-6.

- Mason, Francis K. Hawker Aircraft since 1920. London: Putnam, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-839-9.

- Mason, Francis K. The Hawker Sea Hawk. Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1966.

- Ovčáčík, Michal and Karel Susa. Hawker Sea Hawk. Praha-Strašnice, Czech Republic: Mark I Ltd., 2001. ISBN 80-902559-3-0.

- Taylor, John W.R. "Hawker Sea Hawk." Combat Aircraft of the World from 1909 to the present. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. ISBN 0-425-03633-2.

- Wixey, Ken. "Sea Hawk" Aircraft Modelworld August 1985.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hawker Sea Hawk. |

- Thunder and Lightnings

- Sound of a Sea Hawk flypast

- "Sea Hawk" a 1949 Flight article