Atrazine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

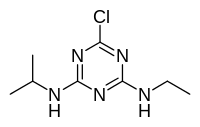

| IUPAC name

1-Chloro-3-ethylamino-5-isopropylamino-2,4,6-triazine | |

| Other names

Atrazine 2-Chloro-4-ethylamino-6-isopropylamino-s-triazine 6-Chloro-N-ethyl-N'-(1-methylethyl)-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diamine | |

| Identifiers | |

| 1912-24-9 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15930 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL15063 |

| ChemSpider | 2169 |

| DrugBank | DB07392 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.017 |

| KEGG | C06551 |

| PubChem | 2256 |

| UNII | QJA9M5H4IM |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8H14ClN5 | |

| Molar mass | 215.69 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | colorless solid |

| Density | 1.187 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 175 °C (347 °F; 448 K) |

| Boiling point | 200 °C (392 °F; 473 K) decomposes[1] |

| 7 mg/100 mL | |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | noncombustible [1] |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

| PEL (Permissible) |

none[1] |

| REL (Recommended) |

TWA 5 mg/m3[1] |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) |

N.D.[1] |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

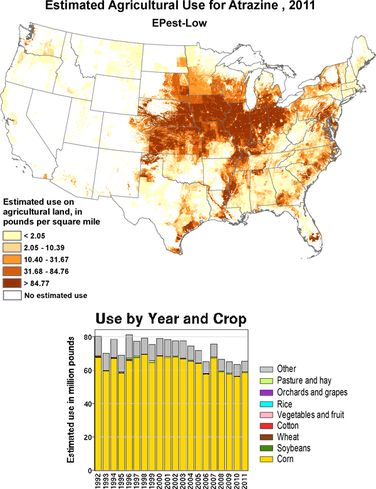

Atrazine is an herbicide of the triazine class. Atrazine is used to prevent pre- and postemergence broadleaf weeds in crops such as maize (corn) and sugarcane and on turf, such as golf courses and residential lawns. It is one of the most widely used herbicides in US[2] and Australian agriculture.[3] It was banned in the European Union in 2004, when the EU found groundwater levels exceeding the limits set by regulators, and Syngenta could neither show that this could be prevented nor that these levels were safe.[4][5]

As of 2001, atrazine was the most commonly detected pesticide contaminating drinking water in the United States.[6]:42 Studies suggest it is an endocrine disruptor, an agent that can alter the natural hormonal system.[7][8] In 2006 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had stated that under the Food Quality Protection Act "the risks associated with the pesticide residues pose a reasonable certainty of no harm",[9] and in 2007, the EPA said that atrazine does not adversely affect amphibian sexual development and that no additional testing was warranted.[10] EPA's 2009 review [11] concluded that "the agency’s scientific bases for its regulation of atrazine are robust and ensure prevention of exposure levels that could lead to reproductive effects in humans."[12] EPA started a registration review in 2013.[13]

The EPA's review has been criticized, and the safety of atrazine remains controversial.[2][8][14][15]

Uses

Atrazine is an herbicide that is used to stop pre- and postemergence broadleaf and grassy weeds in crops such as sorghum, maize, sugarcane, lupins, pine, and eucalypt plantations, and triazine-tolerant canola.[3]

In the United States as of 2014, atrazine was the second-most widely used herbicide after glyphosate,[2] with 76 million pounds of it applied each year.[16][17] Atrazine continues to be one of the most widely used herbicides in Australian agriculture.[3] Its use was banned in the European Union in 2004, when the EU found groundwater levels exceeding the limits set by regulators, and Syngenta could not show that this could be prevented nor that these levels were safe.[4][5]

Its effect on corn yields has been estimated from 1% to 8%, with 3–4% being the conclusion of one economics review.[18][19] In another study looking at combined data from 236 university corn field trials from 1986–2005, atrazine treatments showed an average of 5.7 bushels more per acre than alternative herbicide treatments.[20] Effects on sorghum yields have been estimated to be as high as 20%, owing in part to the absence of alternative weed control products that can be used on sorghum.[21]

Chemistry and biochemistry

Atrazine was invented in 1958 in the Geigy laboratories as the second of a series of 1,3,5-triazines.[22]

Atrazine is prepared from cyanuric chloride, which is treated sequentially with ethylamine and isopropyl amine. Like other triazine herbicides, atrazine functions by binding to the plastoquinone-binding protein in photosystem II, which animals lack. Plant death results from starvation and oxidative damage caused by breakdown in the electron transport process. Oxidative damage is accelerated at high light intensity.[23]

Atrazine's effects in humans and animals primarily involve the endocrine system. Studies suggest that atrazine is an endocrine disruptor that can cause hormone imbalance.[7]

Atrazine has been found to act as an agonist of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1.[24]

Environment

Levels

Atrazine was banned in the European Union in 2004 because of its persistent groundwater contamination.[18]

Atrazine contamination of surface water (lakes, rivers, and streams) has been monitored by the EPA and has consistently exceeded levels of concern in two Missouri watersheds and one in Nebraska.[25] As of 2001, Atrazine was the most commonly detected pesticide in US drinking water.[6][7]:2 Monitoring of atrazine levels in community water systems in 31 high-use states found that levels exceeded levels of concern for infant exposure during at least one year between 1993 and 2001 in 34 of 3670 community water systems using surface water, and in none of 14,500 community water systems using groundwater.[26] Surface water monitoring data from 20 high atrazine use watersheds found peak atrazine levels up to 147 parts per billion, with daily averages in all cases below 10 parts per billion.[27]

Biodegradation

Atrazine remains in soil for a matter of months (although in some soils can persist to at least 4 years)[7] and can migrate from soil to groundwater; once in groundwater, it degrades slowly. It has been detected in groundwater at high levels in some regions of the U.S. where it is used on some crops and turf. The US Environmental Protection Agency expresses concern regarding contamination of surface waters (lakes, rivers, and streams).[7]

Atrazine degrades in soil primarily by the action of microbes. The half-life of atrazine in soil ranges from 13 to 261 days.[28] Atrazine biodegradation can occur by two known pathways:

- Hydrolysis of the C-Cl bond is followed by the ethyl and isopropyl groups, catalyzed by the hydrolase enzymes called AtzA, AtzB, and AtzC. The end product of this process is cyanuric acid, itself unstable with respect to ammonia and carbon dioxide. The best characterized organisms that use this pathway are of Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP.

- Dealkylation of the amino groups gives 2-chloro-4-hydroxy-6-amino-1,3,5-triazine, the degradation of which is unknown. This path also occurs in Pseudomonas species, as well as a number of bacteria.[29][30]

Rates of biodegradation are affected by atrazine's low solubility, thus surfactants may increase the degradation rate. Though the two alkyl moieties readily support growth of certain microorganisms, the atrazine ring is a poor energy source due to the oxidized state of ring carbon. In fact, the most common pathway for atrazine degradation involves the intermediate, cyanuric acid, in which carbon is fully oxidized, thus the ring is primarily a nitrogen source for aerobic microorganisms. Atrazine may be catabolized as a carbon and nitrogen source in reducing environments, and some aerobic atrazine degraders have been shown to use the compound for growth under anoxia in the presence of nitrate as an electron acceptor,[31] a process referred to as a denitrification. When atrazine is used as a nitrogen source for bacterial growth, degradation may be regulated by the presence of alternative sources of nitrogen. In pure cultures of atrazine-degrading bacteria, as well as active soil communitites, atrazine ring nitrogen, but not carbon are assimilated into microbial biomass.[32] Low concentrations of glucose can decrease the bioavailability, whereas higher concentrations promote the catabolism of atrazine.[33]

The genes for enzymes AtzA-C have been found to be highly conserved in atrazine-degrading organisms worldwide. In Pseudomonas sp. ADP, the Atz genes are located noncontiguously on a plasmid with the genes for mercury catabolism. AtzA-C genes have also been found in a Gram-positive bacterium, but are chromosomally located.[34] The insertion elements flanking each gene suggest that they are involved in the assembly of this specialized catabolic pathway.[30] Two options exist for degradation of atrazine using microbes, bioaugmentation or biostimulation.[30] Recent research suggests that microbial adaptation to atrazine has occurred in some fields where the herbicide is used repetitively, resulting in more rapid biodegradation.[35] Like the herbicides trifluralin and alachlor, atrazine is susceptible to rapid transformation in the presence of reduced iron-bearing soil clays, such as ferruginous smectites. In natural environments, some iron-bearing minerals are reduced by specific bacteria in the absence of oxygen, thus the abiotic transformation of herbicides by reduced minerals is viewed as "microbially induced".[36]

Health effects

According to Extension Toxicology Network in the U.S., "The oral median Lethal Dose or LD50 for atrazine is 3090 mg/kg in rats, 1750 mg/kg in mice, 750 mg/kg in rabbits, and 1000 mg/kg in hamsters. The dermal LD50 in rabbits is 7500 mg/kg and greater than 3000 mg/kg in rats. The 1-hour inhalation LC50 is greater than 0.7 mg/L in rats. The 4-hour inhalation LC50 is 5.2 mg/L in rats." The maximum contaminant level is 0.003 mg/L and the reference dose is 0.035 mg/kg/day.[37]

Mammals

A September 2003 review by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) stated that atrazine is "currently under review for pesticide re-registration by the EPA because of concerns that atrazine may cause cancer.", but not enough information was available to "definitely state whether it causes cancer in humans." According to the ATSDR, one of the primary ways that atrazine can affect a person's health is "by altering the way that the reproductive system works. Studies of couples living on farms that use atrazine for weed control found an increase in the risk of preterm delivery, but these studies are difficult to interpret because most of the farmers were men who may have been exposed to several types of pesticides. Little information is available regarding the risks to children, however "[m]aternal exposure to atrazine in drinking water has been associated with low fetal weight and heart, urinary, and limb defects in humans."[39] Incidence of a birth defect known as gastroschisis appears to be higher in areas where surface water atrazine levels are elevated especially when conception occurs in the spring, the time when atrazine is commonly applied.[40]

The EPA determined in 2003 "that atrazine is not likely to cause cancer in humans."[41]

In 2006, the EPA stated, "the risks associated with the pesticide residues pose a reasonable certainty of no harm".[9][10]

In 2007, the EPA said, "studies thus far suggest that atrazine is an endocrine disruptor". The implications for children’s health are related to effects during pregnancy and during sexual development, though few studies are available. In people, risks for preterm delivery and intrauterine growth retardation have been associated with exposure. Atrazine exposure has been shown to result in delays or changes in pubertal development in female rats; conflicting results have been observed in males. Male rats exposed via milk from orally exposed mothers exhibited higher levels of prostate inflammation as adults; immune effects have also been seen in male rats exposed in utero or while nursing.[7] EPA opened a new review in 2009[11] that concluded that "the agency’s scientific bases for its regulation of atrazine are robust and ensure prevention of exposure levels that could lead to reproductive effects in humans."[12] Deborah A. Cory-Slechta, a professor at the University of Rochester in New York has said in 2014, “The way the E.P.A. tests chemicals can vastly underestimate risks.” She has studied atrazine’s effects on the brain and serves on the E.P.A.’s science advisory board. She further stated, “There’s still a huge amount we don’t know about atrazine.”[2]

A Natural Resources Defense Council report from 2009 said that the EPA is ignoring atrazine contamination in surface and drinking water in the central United States.[42]

Research results from the U.S. National Cancer Institute's 2011 Agricultural Health Study concluded, "there was no consistent evidence of an association between atrazine use and any cancer site." The study tracked 57,310 licensed pesticide applicators over 13 years.[43]

A 2011 review of the mammalian reproductive toxicology of atrazine jointly conducted by the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concluded that atrazine was not teratogenic. Reproductive effects in rats and rabbits were only seen at doses that were toxic to the mother. Observed adverse effects in rats included fetal resorption in rates (at doses > 50 mg/kg per day), delays in sexual development in female rats (at doses >30 mg/kg per day), and decreased birth weight (at doses >3.6 mg/kg per day).[44]

A 2014 systematic review, funded by atrazine manufacturer Syngenta, assessed its relation to reproductive health problems. The authors concluded that the quality of most studies was poor and without good quality data, the results were difficult to assess, though it was noted that no single category of negative pregnancy outcome was found consistently across studies. The authors concluded that a causal link between atrazine and adverse pregnancy outcomes was not warranted due to the poor quality of the data and the lack of robust findings across studies. Syngenta was not involved in the design, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data and did not participate in the preparation of the manuscript.[45]

Amphibians

Atrazine has been a suspected teratogen, with some studies reporting causing demasculinization in male northern leopard frogs even at low concentrations,[46][47] and an estrogen disruptor.[48] A 2002 study by Tyrone Hayes, of the University of California, Berkeley, found that exposure caused male tadpoles to turn into hermaphrodites – frogs with both male and female sexual characteristics.[49] A 2003 EPA review of this study concluded that overcrowding, questionable sample handling techniques, and the failure of the authors to disclose key details including sample sizes, dose-response effects, and the variability of observed effects made it difficult to assess the study's credibility and ecological relevance.[50] According to Hayes in 2004, all of the studies that rejected the hermaphroditism hypothesis were plagued by poor experimental controls and were funded by Syngenta, suggesting conflict of interest.[51] A 2005 Syngenta-funded study, requested by EPA and conducted under EPA guidance and inspection, was unable to reproduce Hayes´ results.[52]

The EPA's Scientific Advisory Panel examined relevant studies and concluded in 2010, "atrazine does not adversely affect amphibian gonadal development based on a review of laboratory and field studies."[10] It recommended proper study design for further investigation. As required by the EPA, Syngenta conducted two experiments under Good Laboratory Practices (GLP) and inspection by EPA and German regulatory authorities, concluding 2009 that "long-term exposure of larval X. laevis to atrazine at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 100 μg/l does not affect growth, larval development, or sexual differentiation."[53] A 2008 report cited the independent work of researchers in Japan, who were unable to replicate Hayes' work. "The scientists found no hermaphrodite frogs; no increase in aromatase as measured by aromatase mRNA induction; and no increase in vitellogenin, another marker of feminization."[54]

A 2007 study examined the relative importance of environmentally relevant concentrations of atrazine on trematode cercariae versus tadpole defense against infection. Its principal finding was that susceptibility of wood frog tadpoles to infection by E. trivolvis is increased only when hosts were exposed to an atrazine concentration of 30 ng/L and not to 3 ng/L.[55]

A 2008 study reported that tadpoles developed deformed hearts and impaired kidneys and digestive systems when chronically exposed to atrazine concentrations of 10,000 ppb in their early stages of life. Tissue malformation may have been induced by ectopic programmed cell death, although a mechanism was not identified.[56]

A 2010 Hayes study concluded that atrazine rendered 75% of male frogs sterile and turned one in 10 into females.[57][58]

In 2010, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) tentatively concluded that environmental atrazine "at existing levels of exposure" was not affecting amphibian populations in Australia consistent with the 2007 EPA findings.[59] APVMA responded to Hayes' 2010 published paper, that his findings "do not provide sufficient evidence to justify a reconsideration of current regulations which are based on a very extensive dataset."[59]

A 2015 EPA article discussed the Hayes/Syngenta conflict to illustrate both financial and nonfinancial conflicts of interest. The authors concluded, "Statements by Hayes and Syngenta suggest that their scientific differences have developed a personal aspect that casts doubt on their scientific objectivity".[60]

Class action lawsuit

In 2012, Syngenta, manufacturer of atrazine, was the defendant in a class-action lawsuit concerning the levels of atrazine in human water supplies. Syngenta agreed to pay $105 million to reimburse more than one thousand water systems for "the cost of filtering atrazine from drinking water". The company denied all wrongdoing.[2] [61][62]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0043". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A Valuable Reputation: Tyrone Hayes said that a chemical was harmful, its maker pursued him" by Rachel Aviv, The New Yorker, 10 February 2014

- 1 2 3 "Chemical Review: Atrazine". Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- 1 2 European Commission. 2004/248/EC: Commission Decision of 10 March 2004 concerning the non-inclusion of atrazine in Annex I to Council Directive 91/414/EEC and the withdrawal of authorisations for plant protection products containing this active substance (Text with EEA relevance) (notified under document number C(2004) 731) Decision 2004/248/EC - Official Journal L 078, Decision 2004/248/EC. March 16, 2004: Quote: "(9)Assessments made on the basis of the information submitted have not demonstrated that it may be expected that, under the proposed conditions of use, plant protection products containing atrazine satisfy in general the requirements laid down in Article 5(1)(a) and (b) of Directive 91/414/EEC. In particular, available monitoring data were insufficient to demonstrate that in large areas concentrations of the active substance and its breakdown products will not exceed 0,1 μg/l in groundwater. Moreover it cannot be assured that continued use in other areas will permit a satisfactory recovery of groundwater quality where concentrations already exceed 0,1 μg/l in groundwater. These levels of the active substance exceed the limits in Annex VI to Directive 91/414/EEC and would have an unacceptable effect on groundwater." (10) Atrazine should therefore not be included in Annex I to Directive 91/414/EEC. (11) Measures should be taken to ensure that existing authorisations for plant protection products containing atrazine are withdrawn within a prescribed period and are not renewed and that no new authorisations for such products are granted."

- 1 2 Danny Hakimfeb for the New York Times. February 23, 2015. A Pesticide Banned, or Not, Underscores Trans-Atlantic Trade Sensitivities

- 1 2 Gilliom RJ et al. US Geological Survey The Quality of Our Nation’s Waters: Pesticides in the Nation’s Streams and Ground Water, 1992–2001 March 2006, Revised February 15, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Atrazine: Chemical Summary. Toxicity and Exposure Assessment for Children’s Health (PDF) (Report). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2007-04-24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-16.

- 1 2 Hayes, Tyrone B.; Anderson, Lloyd L.; Beasley, Val R.; de Solla, Shane R.; Iguchi, Taisen; et al. (2011). "Demasculinization and feminization of male gonads by atrazine: Consistent effects across vertebrate classes". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 127 (1–2): 64–73. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.03.015. PMID 21419222.

- 1 2 Triazine Cumulative Risk Assessment and Atrazine, Simazine, and Propazine Decisions Archived June 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., June 22, 2006, EPA.

- 1 2 3 Atrazine Updates: Amphibians, April 2010, EPA.

- 1 2 EPA Begins New Scientific Evaluation of Atrazine, October 7, 2009, EPA.

- 1 2 EPA Atrazine Updates: Scientific Peer Review—Human Health Current as of January 2013. Accessed March 15, 2014

- ↑ EPA [ww.epa.gov/pesticides/reregistration/atrazine/atrazine_update.htm#amphibian Atrazine Updates: Scientific Peer Review—Amphibians] Current as of January 2013. Accessed March 15, 2014

- ↑ Duhigg, Charles (August 22, 2009). "Debating How Much Weed Killer Is Safe in Your Water Glass". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-05-02.

- ↑ Tillitt DE, Papoulias DM, Whyte JJ, Richter CA (2010). "Atrazine reduces reproduction in fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas)". Aquat. Toxicol. 99 (2): 149–59. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.04.011. PMID 20471700.

- ↑ Walsh, Edward (2003-02-01). "EPA Stops Short of Banning Herbicide". Washington Post. pp. A14. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ "Restricted Use Products (RUP) Report: Six Month Summary List". Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- 1 2 Ackerman, Frank (2007). "The economics of atrazine" (PDF). International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 13 (4): 437–445. doi:10.1179/oeh.2007.13.4.437. PMID 18085057.

- ↑ "BioOne Online Journals - A Rationale for Atrazine Stewardship in Corn".

- ↑ Fawcett, Richard S. "Twenty Years of University Corn Yield Data: With and Without Atrazine", North Central Weed Science Society Archived March 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine., 2008

- ↑ "Market-level assessment of the economic benefits of atrazine in the United States - Mitchell - 2014 - Pest Management Science - Wiley Online Library".

- ↑ Wolfgang Krämer (2007). Modern Crop Protection Compounds, Volume 1. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 9783527314966.

- ↑ Appleby, Arnold P.; Müller, Franz; Carpy, Serge (2001). "Weed Control". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_165. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ↑ Prossnitz, Eric R.; Barton, Matthias (2014). "Estrogen biology: New insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 389 (1-2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. ISSN 0303-7207.

- ↑ "Atrazine Updates | Pesticides | US EPA". Epa.gov. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ↑ "www.epa.gov" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25.

- ↑ Schmoldt A, Benthe HF, Haberland G (September 1975). "Digitoxin metabolism by rat liver microsomes". Biochem. Pharmacol. 24 (17): 1639–41. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(75)90094-5. PMID 10.

- ↑ Interim Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Atrazine Archived June 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., U.S. EPA, January, 2003.

- ↑ Zeng Y, Sweeney CL, Stephens S, Kotharu P. (2004). Atrazine Pathway Map. Wackett LP. Biodegredation Database.

- 1 2 3 Wackett, L. P.; Sadowsky, M. J.; Martinez, B.; Shapir, N. (January 2002). "Biodegradation of atrazine and related s-triazine compounds: from enzymes to field studies". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 58 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1007/s00253-001-0862-y. PMID 11831474.

- ↑ Crawford, J. J., G.K. Sims, R.L. Mulvaney, and M. Radosevich (1998). "Biodegradation of atrazine under denitrifying conditions". Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 49 (5): 618–623. doi:10.1007/s002530051223. PMID 9650260.

- ↑ Bichat, F., G.K. Sims, and R.L. Mulvaney (1999). "Microbial utilization of heterocyclic nitrogen from atrazine". Soil Science Society of America Journal. 63: 100–110. doi:10.2136/sssaj1999.03615995006300010016x.

- ↑ Ralebitso TK, Senior E, van Verseveld HW (2002). "Microbial aspects of atrazine degradation in natural environments". Biodegradation. 13: 11–19. doi:10.1023/A:1016329628618.

- ↑ Cai B, Han Y, Liu B, Ren Y, Jiang S (2003). "Isolation and characterization of an atrazine-degrading bacterium from industrial wastewater in China". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 36 (5): 272–276. doi:10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01307.x. PMID 12680937.

- ↑ Krutz, L.J., D.L. Shaner, C. Accinelli, R.M. Zablotowicz, and W.B. Henry (2008). "Atrazine dissipation in s-triazine-adapted and non-adapted soil from Colorado and Mississippi: Implications of enhanced degradation on atrazine fate and transport parameters". Journal of Environmental Quality. 37 (3): 848–857. doi:10.2134/jeq2007.0448. PMID 18453406.

- ↑ Xu, J., J. W. Stucki, J. Wu, J. Kostka, and G. K. Sims (2001). "Fate of atrazine and alachlor in redox-treated ferruginous smectite". Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry. 20 (12): 2717–2724. doi:10.1002/etc.5620201210.

- ↑ Pesticide Information Profile: Atrazine, Extension Toxicology Network (Cooperative Extension Offices of Cornell University, Oregon State University, the University of Idaho, and the University of California at Davis and the Institute for Environmental Toxicology, Michigan State University), June 1996.

- ↑ USGS Pesticide Use Maps

- ↑ "Public Health Statement for Atrazine". Toxic Substances Portal - Atrazine. Center for Disease Control, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Division of Toxicology and Human Health Sciences. September 2003. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Agricultural-related chemical exposures, season of conception, and risk of gastroschisis in Washington State.". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. March 2010. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ↑ Interim Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Atrazine, U.S. EPA, January, 2003.

- ↑ "How the EPA is Ignoring Atrazine Contamination in Surface and Drinking Water in the Central United States" (PDF). Natural Resources Defense Council. The New York Times. August 2009.

- ↑ Beane Freeman, Laura E. (2011) Atrazine and Cancer Incidence Among Pesticide Applicators in the Agricultural Health Study (1994–2007). Environmental Health Perspectives.

- ↑ "Chemical Hazards in Drinking Water - Atrazine" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ↑ Goodman, M; Mandel, J. S.; Desesso, J. M.; Scialli, A. R. (2014). "Atrazine and pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review of epidemiologic evidence". Birth Defects Research Part B: Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology. 101 (3): 215–36. doi:10.1002/bdrb.21101. PMC 4265844

. PMID 24797711.

. PMID 24797711. - ↑ Jennifer Lee (2003-06-19). "Popular Pesticide Faulted for Frogs' Sexual Abnormalities". The New York Times.

- ↑ Tyrone Hayes; Kelly Haston; Mable Tsui; Anhthu Hoang; Cathryn Haeffele; Aaron Vonk (2003). "Atrazine-Induced Hermaphroditism at 0.1 ppb in American Leopard Frogs" (Free full text). Environmental Health Perspectives. 111 (4): 568–75. doi:10.1289/ehp.5932. PMC 1241446

. PMID 12676617.

. PMID 12676617. - ↑ Mizota, K.; Ueda, H. (2006). "Endocrine Disrupting Chemical Atrazine Causes Degranulation through Gq/11 Protein-Coupled Neurosteroid Receptor in Mast Cells". Toxicological Sciences. 90 (2): 362–8. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfj087. PMID 16381660.

- ↑ Briggs, Helen. (April 15, 2002), Pesticide 'causes frogs to change sex'. BBC News. Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ↑ "www.epa.gov" (PDF). EPA Scientific Advisory Panel. June 2003.

- ↑ Hayes, TB (2004). "There Is No Denying This: Defusing the Confusion about Atrazine". BioScience. 54 (112): 1138–1149. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[1138:TINDTD]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ↑ Jooste; Du Preez, LH; Carr, JA; Giesy, JP; Gross, TS; Kendall, RJ; Smith, EE; Van Der Kraak, GL; Solomon, KR; et al. (2005). "Gonadal Development of Larval Male Xenopus laevis Exposed to Atrazine in Outdoor Microcosms". Environ. Sci. Technol. 39 (14): 5255–5261. Bibcode:2005EnST...39.5255J. doi:10.1021/es048134q. PMID 16082954.

- ↑ Kloas, W; Lutz, I; Springer, T; Krueger, H; Wolf, J; Holden, L; Hosmer, A (2009). "Does atrazine influence larval development and sexual differentiation in Xenopus laevis?". Toxicological Sciences. 107 (2): 376–84. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfn232. PMC 2639758

. PMID 19008211.

. PMID 19008211. - ↑ Renner, Rebecca (May 2008). "Atrazine Effects in Xenopus Aren't Reproducible (Perspective)" (PDF). Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (10): 3491–3493. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.3491R. doi:10.1021/es087113j.

- ↑ Koprivnikar, Janet; Forbes, Mark R.; Baker, Robert L. (2007). "Contaminant Effects on Host–Parasite Interactions: Atrazine, Frogs, and Trematodes". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. American Chemistry Society. 26 (10): 2166–70. doi:10.1897/07-220.1. PMID 17867892.

- ↑ Lenkowski JR, Reed JM, Deininger L, McLaughlin KA (2008). "Perturbation of organogenesis by the herbicide atrazine in the amphibian Xenopus laevis". Environ. Health Perspect. 116 (2): 223–30. doi:10.1289/ehp.10742. PMC 2235211

. PMID 18288322.

. PMID 18288322. - ↑ Hayes, TB; Khoury, V; Narayan, A; Nazir, M; Park, A; Brown, T; Adame, L; Chan, E; et al. (2010). "Atrazine induces complete feminization and chemical castration in male African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (10): 4612–7. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.4612H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909519107. PMC 2842049

. PMID 20194757.

. PMID 20194757. - ↑ "Pesticide atrazine can turn male frogs into females" (Press release). University of California. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- 1 2 Chemicals in the News: Atrazine, Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority, Original June 30, 2010, Archived by Internet Archive July 4, 2010

- ↑ Suter, Glenn; Cormier, Susan (2015). "The problem of biased data and potential solutions for health and environmental assessments". Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal. 21. doi:10.1080/10807039.2014.974499. Retrieved 2015-02-11. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ City of Greenville v. Syngenta Crop Protection, Inc., and Syngenta AG Case No. 3:10-cv-00188-JPG-PMF, accessed August 23, 2013

- ↑ Clare Howard for Environmental Health News. June 17, 2013 Special Report: Syngenta's campaign to protect atrazine, discredit critics.

External links

- atrazine.com – Syngenta's page about atrazine

- Atrazinelovers: an anti-atrazine website – maintained by Tyrone Hayes

- Atrazine - CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Atrazine in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)