Clomifene

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | per os |

| ATC code | G03GB02 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | High (>90%) |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (with enterohepatic circulation) |

| Biological half-life | 5-7 days |

| Excretion | Mainly renal, some biliary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

911-45-5 |

| PubChem (CID) | 2800 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 4159 |

| DrugBank |

DB00882 |

| ChemSpider |

2698 |

| UNII |

1HRS458QU2 |

| KEGG |

D07726 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:3752 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1200667 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.011.826 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

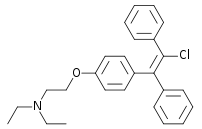

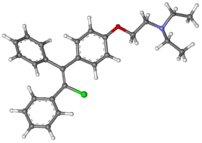

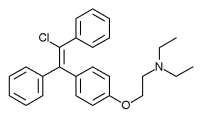

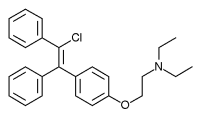

| Formula | C26H28ClNO |

| Molar mass | 406 or 598.10 g/mol (with citrate) |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Clomifene (INN) or clomiphene (USAN) (originally marketed as Clomid and subsequently under many brand names)[1] is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) of the triphenylethylene group. It revolutionized the treatment of female infertility and marked the beginning of the modern era of assisted reproductive technology.[2] It became the most widely prescribed drug for ovulation induction to reverse anovulation or oligoovulation.[3]

It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[4]

Medical uses

Clomifene is useful in those who are infertile due to anovulation or oligoovulation.[5] Evidence is lacking for the use of clomifene in those who are infertile without a known reason.[6] In such cases, studies have observed a clinical pregnancy rate 5.6% per cycle with clomifene treatment vs. 1.3%–4.2% per cycle without treatment.[5]

Clomifene has also been used with other assisted reproductive technology to increase success rates of these other modalities.[7]

Proper timing of the drug is important; it should be taken starting on about the fifth day of the cycle, and there should be frequent intercourse.[8][9][5]

The following procedures may be used to monitor induced cycles:[5]

- Follicular monitoring with vaginal ultrasound, starting 4–6 days after last pill. Serial transvaginal ultrasound can reveal the size and number of developing follicles. It can also provide presumptive evidence of ovulation such as sudden collapse of the preovulatory follicle, and an increase in fluid volume in the rectouterine pouch. After ovulation, it may reveal signs of luteinization such as loss of clearly defined follicular margins and appearance of internal echoes.

- Serum estradiol levels, starting 4–6 days after last pill

- Post-coital test 1–3 days before ovulation to check whether there are at least 5 progressive sperm per HPF

- Adequacy of LH surge by urine LH surge tests 3 to 4 days after last clomifene pill

- Mid-luteal progesterone, with at least 10 ng/ml 7–9 days after ovulation being regarded as adequate.

Repeat dosing: This 5-day treatment course can be repeated every 30 days. The dosage may be increased by 50-mg increments in subsequent cycles until ovulation is achieved.[5] It is not recommended by the manufacturer to use clomifene for more than 6 cycles.[8][10]

It is no longer recommended to perform an ultrasound examination to exclude any significant residual ovarian enlargement before each new treatment cycle.[5]

Clomifene is sometimes used in the treatment of male hypogonadism as an alternative to testosterone replacement therapy.[11] It has been found to increase testosterone levels by 2- to 2.5-fold in hypogonadal men.[11]

Adverse events

The most common adverse drug reaction associated with the use of clomifene (>10% of people) is reversible ovarian enlargement.[8]

Less common effects (1-10% of people) include visual symptoms (blurred vision, double vision, floaters, eye sensitivity to light, scotomata), headaches, vasomotor flushes (or hot flashes), light sensitivity and pupil constriction, abnormal uterine bleeding and/or abdominal discomfort.[8]

Rare adverse events (<1% of people) include: high blood level of triglycerides, liver inflammation, reversible baldness and/or ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.[8]

Clomifene can lead to multiple ovulation, hence increasing the chance of twins (10% of births instead of ~1% in the general population) and triplets.

Some studies have suggested that clomifene citrate if used for more than a year may increase the risk of ovarian cancer.[6] This may only be the case in those who have never been and do not become pregnant.[12] Subsequent studies have failed to corroborate those findings.[5] This however is disputed and some feel there is no significant increase in risk.[13]

The incidence of fetal and neonatal abnormalities for patients on clomifene for fertility is similar to that seen in the general population. There is no data to suggest a higher rate of congenital anomalies or spontaneous abortions after using this drug.[8]

Mechanism of action

Clomifene inhibits estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus, inhibiting negative feedback of estrogen on gonadotropin release, leading to up-regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis.[14] Zuclomifene, a more active isomer, stays bound for longer periods of time. Clomifene is not a steroid drug.

In normal physiologic female hormonal cycling, at 7 days past ovulation, high levels of estrogen and progesterone produced from the corpus luteum inhibit GnRH, FSH and LH at the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary. If fertilization does not occur in the post-ovulation period the corpus luteum disintegrates due to a lack of beta-hCG. This would normally be produced by the embryo in the effort of maintaining progesterone and estrogen levels during pregnancy.

Therapeutically, clomifene is given early in the menstrual cycle. It is typically prescribed beginning on day 3 and continuing for 5 days. By that time, FSH level is rising steadily, causing development of a few follicles. Follicles in turn produce the estrogen, which circulates in serum. In the presence of clomifene, the body perceives a low level of estrogen, similar to day 22 in the previous cycle. Since estrogen can no longer effectively exert negative feedback on the hypothalamus, GnRH secretion becomes more rapidly pulsatile, which results in increased pituitary gonadotropin (FSH, LH) release. (It should be noted that more rapid, lower amplitude pulses of GnRH lead to increased LH/FSH secretion, while more irregular, larger amplitude pulses of GnRH leads to a decrease in the ratio of LH/FSH.) Increased FSH level causes growth of more ovarian follicles, and subsequently rupture of follicles resulting in ovulation. Ovulation occurs most often 6–7 days after a course of clomifene.

Chemistry

Clomifene is a mixture of two geometric isomers, enclomifene (E-clomifene) and zuclomifene (Z-clomifene). These two isomers have been found to contribute to the mixed estrogenic and anti-estrogenic properties of clomifene.[2]

|

|

History

A team at William S. Merrell Chemical Company led by Frank Palopoli synthesized clomifene in 1956; after its biological activity was confirmed a patent was filed and issued in November 1959.[2][15] Scientists at Merrell had previously synthesized chlorotrianisene and ethamoxytriphetol.[2]

Clinical studies were conducted under an Investigational New Drug Application; it was third drug for which an IND had been filed under the 1962 Kefauver Harris Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that had been been passed in response to the thalidomide tragedy.[2] It was approved for marketing in 1967 under the brand name Clomid.[2][16] It was first used to treat cases of oligomenorrhea but was expanded to include treatment of anovulation when women undergoing treatment had higher than expected rates of pregnancy.[17]

The drug is widely considered to have been a revolution in the treatment of female infertility, the beginning of the modern era of assisted reproductive technology, and the beginning of what in the words of Eli Y. Adashi, was "the onset of the US multiple births epidemic".[2][18]

The company was acquired by Dow Chemical in 1980,[19][20] and in 1989 Dow Chemical acquired 67 percent interest of Marion Laboratories, which was renamed Marion Merrell Dow.[21] In 1995 Hoechst AG acquired the pharmaceutical business of Marion Merrell Dow.[22] Hoechst in turn became part of Aventis in 1999,[23]:9–11 and subsequently a part of Sanofi.[24]

Society and culture

Regulation

Clomifene is included on the World Anti-Doping Agency list of illegal doping agents in sport.[25]

Brand names

Clomifene is marketed under many brand names worldwide, including Beclom, Bemot, Biogen, Blesifen, Chloramiphene, Clomene, ClomHEXAL, Clomi, Clomid, Clomidac, Clomifen, Clomifencitrat, Clomifene, Clomifène, Clomifene citrate , Clomifeni citras, Clomifeno , Clomifert, Clomihexal, Clomiphen, Clomiphene, Clomiphene Citrate , Cloninn, Clostil, Clostilbegyt, Clovertil, Clovul, Dipthen, Dufine, Duinum, Fensipros, Fertab, Fertec, Fertex, Ferticlo, Fertil, Fertilan, Fertilphen, Fertin, Fertomid, Ferton, Fertotab, Fertyl, Fetrop, Folistim, Genoclom, Genozym, Hete, I-Clom, Ikaclomin, Klofit, Klomen, Klomifen, Lomifen, MER 41, Milophene, Ofertil, Omifin, Ova-mit, Ovamit, Ovinum, Ovipreg, Ovofar, Ovuclon, Ovulet, Pergotime, Pinfetil, Profertil, Prolifen, Provula, Reomen, Serofene, Serophene, Serpafar, Serpafar, Surole, Tocofeno, and Zimaquin.[1]

Research

Clomifene was studied for treatment and prevention of breast cancer, but issues with toxicity led to abandonment of this indication, as did the discovery of tamoxifen.[26] Like the structurally related drug triparanol, clomifene is known to inhibit the enzyme 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase and increase circulating desmosterol levels, making it unfavorable for extended use in breast cancer due to risk of side effects like irreversible cataracts.[27][28]

See also

References

- 1 2 "International brands of clomifene -". Drugs.com. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dickey, RP; Holtkamp, DE (1996). "Development, pharmacology and clinical experience with clomiphene citrate." (PDF). Human reproduction update. 2 (6): 483–506. PMID 9111183.

- ↑ Jerome Frank Strauss; Robert L. Barbieri (13 September 2013). Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 518–. ISBN 978-1-4557-2758-2.

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Use of clomiphene citrate in infertile women: a committee opinion". Fertil. Steril. 100 (2): 341–8. August 2013. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.05.033. PMID 23809505.

- 1 2 Hughes, E; Brown, J; Collins, JJ; Vanderkerchove, P (Jan 20, 2010). "Clomiphene citrate for unexplained subfertility in women.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD000057. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000057.pub2. PMID 20091498.

- ↑ Seli, Emre. "Ovulation induction with clomiphene citrate". UpToDate. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Clomiphene citrate tablets label" (PDF). Revised October 2012: FDA. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Clomifene 50mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". Last updated July 2007: UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ Trabert, B.; Lamb, E. J.; Scoccia, B.; Moghissi, K. S.; Westhoff, C. L.; Niwa, S.; Brinton, L. A. (2013). "Ovulation-inducing drugs and ovarian cancer risk: Results from an extended follow-up of a large US infertility cohort". Fertility and Sterility. 100 (6): 1660–6. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.008. PMID 24011610.

- 1 2 Bach, Phil Vu; Najari, Bobby B.; Kashanian, James A. (2016). "Adjunct Management of Male Hypogonadism". Current Sexual Health Reports. doi:10.1007/s11930-016-0089-7. ISSN 1548-3584.

- ↑ Trabert, B; Lamb, EJ; Scoccia, B; Moghissi, KS; Westhoff, CL; Niwa, S; Brinton, LA (Dec 2013). "Ovulation-inducing drugs and ovarian cancer risk: results from an extended follow-up of a large United States infertility cohort.". Fertility and Sterility. 100 (6): 1660–6. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.008. PMID 24011610.

- ↑ Gadducci, A; Guerrieri, ME; Genazzani, AR (Jan 2013). "Fertility drug use and risk of ovarian tumors: a debated clinical challenge.". Gynecological Endocrinology. 29 (1): 30–5. doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.705382. PMID 22946709.

- ↑ DrugBank > Clomifene. Updated on April 19, 2011

- ↑ Allen, R.E., Palopoli, F.P., Schumann, E.L. and Van Campen, M.G. Jr. (1959) U.S. Patent No. 2,914,563, Nov. 24, 1959.

- ↑ Holtkamp DE, Greslin JG, Root CA, Lerner LJ (October 1960). "Gonadotrophin inhibiting and anti-fecundity effects of chloramiphene". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 105: 197–201. doi:10.3181/00379727-105-26054. PMID 13715563.

- ↑ Hughes E, Collins J, Vandekerckhove P (2000). "Clomiphene citrate for ovulation induction in women with oligo-amenorrhoea". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD000056. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000056. PMID 10796477.

- ↑ Adashi, Eli Y. (Fall 2014). "Iatrogenic Birth Plurality: The Challenge and Its Possible Solution" (PDF). Harvard Health Policy Review. 14 (1): 9–10.

- ↑ Lee, Patrick (18 July 1989). "Dow Chemical to Get Control of Marion Labs : $5-Billion-Plus Deal Is an Effort to Diversify". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Times, Winston Williams, Special To The New York (11 February 1981). "Dow Broadens Product Lines". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ↑ Lee, Patrick (18 July 1989). "Dow Chemical to Get Control of Marion Labs : $5-Billion-Plus Deal Is an Effort to Diversify". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Hoechst AG to Buy Marion Merrell Dow / Acquisition worth over $7 billion". San Francisco Chronicle. Reuters. May 5, 1995.

- ↑ Arturo Bris and Christos Cabolis, Corporate Governance Convergence Through Cross-Border Mergers The Case of Aventis, Chapter 4 in Corporate Governance and Regulatory Impact on Mergers and Acquisitions: Research and Analysis on Activity Worldwide Since 1990. Eds Greg N. Gregoriou, Luc Renneboog. Academic Press, 26 July 2007

- ↑ Timmons, Heather; Bennhold, Katrin (27 April 2004). "France Helped Broker the Aventis-Sanofi Deal". The New York Times.

- ↑ The WADA Prohibited List 2016 (listed as clomiphene)

- ↑ Maximov, PY; Lee, TM; Jordan, VC (May 2013). "The discovery and development of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for clinical practice.". Current clinical pharmacology. 8 (2): 135–55. PMC 3624793

. PMID 23062036.

. PMID 23062036. - ↑ Hormones and Breast Cancer. Elsevier. 25 June 2013. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-0-12-416676-9.

- ↑ Maximov, Philipp Y.; McDaniel, Russell E.; Jordan, V. Craig (2013). "Tamoxifen Goes Forward Alone": 31–46. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-0664-0_2. ISSN 2296-6064.