Ceramic

A ceramic is an inorganic, nonmetallic[lower-alpha 1] solid material comprising metal, nonmetal or metalloid atoms primarily held in ionic and covalent bonds.

The crystallinity of ceramic materials ranges from highly oriented to semi-crystalline, and often completely amorphous (e.g., glasses). Varying crystallinity and electron consumption in the ionic and covalent bonds cause most ceramic materials to be good thermal and electrical insulators (extensively researched in ceramic engineering). With such a large range of possible options for the composition/structure of a ceramic (e.g. nearly all of the elements, nearly all types of bonding, and all levels of crystallinity), the breadth of the subject is vast, and identifiable attributes (e.g. hardness, toughness, electrical conductivity, etc.) are hard to specify for the group as a whole. General properties such as high melting temperature, high hardness, poor conductivity, high moduli of elasticity, chemical resistance and low ductility are the norm,[1] with known exceptions to each of these rules (e.g. piezoelectric ceramics, glass transition temperature, superconductive ceramics, etc.). Many composites, such as fiberglass and carbon fiber, while containing ceramic materials, are not considered to be part of the ceramic family.[2]

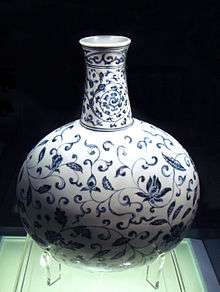

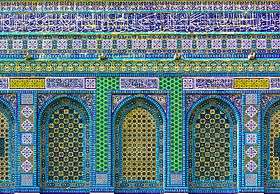

The earliest ceramics made by humans were pottery objects (i.e. pots or vessels) or figurines made from clay, either by itself or mixed with other materials like silica, hardened, sintered, in fire. Later ceramics were glazed and fired to create smooth, colored surfaces, decreasing porosity through the use of glassy, amorphous ceramic coatings on top of the crystalline ceramic substrates.[3] Ceramics now include domestic, industrial and building products, as well as a wide range of ceramic art. In the 20th century, new ceramic materials were developed for use in advanced ceramic engineering, such as in semiconductors.

The word "ceramic" comes from the Greek word κεραμικός (keramikos), "of pottery" or "for pottery",[4] from κέραμος (keramos), "potter's clay, tile, pottery".[5] The earliest known mention of the root "ceram-" is the Mycenaean Greek ke-ra-me-we, "workers of ceramics", written in Linear B syllabic script.[6] The word "ceramic" may be used as an adjective to describe a material, product or process, or it may be used as a noun, either singular, or, more commonly, as the plural noun "ceramics".[7]

Types of ceramic material

A ceramic material is an inorganic, non-metallic, often crystalline oxide, nitride or carbide material. Some elements, such as carbon or silicon, may be considered ceramics. Ceramic materials are brittle, hard, strong in compression, weak in shearing and tension. They withstand chemical erosion that occurs in other materials subjected to acidic or caustic environments. Ceramics generally can withstand very high temperatures, such as temperatures that range from 1,000 °C to 1,600 °C (1,800 °F to 3,000 °F). Glass is often not considered a ceramic because of its amorphous (noncrystalline) character. However, glassmaking involves several steps of the ceramic process and its mechanical properties are similar to ceramic materials.

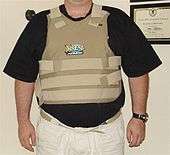

Traditional ceramic raw materials include clay minerals such as kaolinite, whereas more recent materials include aluminium oxide, more commonly known as alumina. The modern ceramic materials, which are classified as advanced ceramics, include silicon carbide and tungsten carbide. Both are valued for their abrasion resistance, and hence find use in applications such as the wear plates of crushing equipment in mining operations. Advanced ceramics are also used in the medicine, electrical, electronics industries and body armor.

Crystalline ceramics

Crystalline ceramic materials are not amenable to a great range of processing. Methods for dealing with them tend to fall into one of two categories – either make the ceramic in the desired shape, by reaction in situ, or by "forming" powders into the desired shape, and then sintering to form a solid body. Ceramic forming techniques include shaping by hand (sometimes including a rotation process called "throwing"), slip casting, tape casting (used for making very thin ceramic capacitors, e.g.), injection molding, dry pressing, and other variations. Details of these processes are described in the two books listed below. A few methods use a hybrid between the two approaches.

Noncrystalline ceramics

Noncrystalline ceramics, being glass, tend to be formed from melts. The glass is shaped when either fully molten, by casting, or when in a state of toffee-like viscosity, by methods such as blowing into a mold. If later heat treatments cause this glass to become partly crystalline, the resulting material is known as a glass-ceramic, widely used as cook-top and also as a glass composite material for nuclear waste disposal.

Properties of ceramics

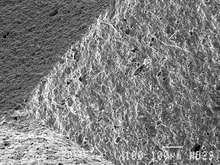

The physical properties of any ceramic substance are a direct result of its crystalline structure and chemical composition. Solid state chemistry reveals the fundamental connection between microstructure and properties such as localized density variations, grain size distribution, type of porosity and second-phase content, which can all be correlated with ceramic properties such as mechanical strength σ by the Hall-Petch equation, hardness, toughness, dielectric constant, and the optical properties exhibited by transparent materials.

Physical properties of chemical compounds which provide evidence of chemical composition include odor, colour, volume, density (mass / volume), melting point, boiling point, heat capacity, physical form at room temperature (solid, liquid or gas), hardness, porosity, and index of refraction.

Ceramography is the art and science of preparation, examination and evaluation of ceramic microstructures. Evaluation and characterization of ceramic microstructures is often implemented on similar spatial scales to that used commonly in the emerging field of nanotechnology: from tens of angstroms (A) to tens of micrometers (µm). This is typically somewhere between the minimum wavelength of visible light and the resolution limit of the naked eye.

The microstructure includes most grains, secondary phases, grain boundaries, pores, micro-cracks, structural defects and hardness microindentions. Most bulk mechanical, optical, thermal, electrical and magnetic properties are significantly affected by the observed microstructure. The fabrication method and process conditions are generally indicated by the microstructure. The root cause of many ceramic failures is evident in the cleaved and polished microstructure. Physical properties which constitute the field of materials science and engineering include the following:

Mechanical properties

_disk.jpg)

Mechanical properties are important in structural and building materials as well as textile fabrics. They include the many properties used to describe the strength of materials such as: elasticity / plasticity, tensile strength, compressive strength, shear strength, fracture toughness & ductility (low in brittle materials), and indentation hardness.

In modern materials science, fracture mechanics is an important tool in improving the mechanical performance of materials and components. It applies the physics of stress and strain, in particular the theories of elasticity and plasticity, to the microscopic crystallographic defects found in real materials in order to predict the macroscopic mechanical failure of bodies. Fractography is widely used with fracture mechanics to understand the causes of failures and also verify the theoretical failure predictions with real life failures.

Ceramic materials are usually ionic or covalent bonded materials, and can be crystalline or amorphous. A material held together by either type of bond will tend to fracture before any plastic deformation takes place, which results in poor toughness in these materials. Additionally, because these materials tend to be porous, the pores and other microscopic imperfections act as stress concentrators, decreasing the toughness further, and reducing the tensile strength. These combine to give catastrophic failures, as opposed to the normally much more gentle failure modes of metals.

These materials do show plastic deformation. However, due to the rigid structure of the crystalline materials, there are very few available slip systems for dislocations to move, and so they deform very slowly. With the non-crystalline (glassy) materials, viscous flow is the dominant source of plastic deformation, and is also very slow. It is therefore neglected in many applications of ceramic materials.

To overcome the brittle behaviour, ceramic material development has introduced the class of ceramic matrix composite materials, in which ceramic fibers are embedded and with specific coatings are forming fiber bridges across any crack. This mechanism substantially increases the fracture toughness of such ceramics. The ceramic disc brakes are, for example using a ceramic matrix composite material manufactured with a specific process.

Electrical properties

Semiconductors

Some ceramics are semiconductors. Most of these are transition metal oxides that are II-VI semiconductors, such as zinc oxide.

While there are prospects of mass-producing blue LEDs from zinc oxide, ceramicists are most interested in the electrical properties that show grain boundary effects.

One of the most widely used of these is the varistor. These are devices that exhibit the property that resistance drops sharply at a certain threshold voltage. Once the voltage across the device reaches the threshold, there is a breakdown of the electrical structure in the vicinity of the grain boundaries, which results in its electrical resistance dropping from several megohms down to a few hundred ohms. The major advantage of these is that they can dissipate a lot of energy, and they self-reset – after the voltage across the device drops below the threshold, its resistance returns to being high.

This makes them ideal for surge-protection applications; as there is control over the threshold voltage and energy tolerance, they find use in all sorts of applications. The best demonstration of their ability can be found in electrical substations, where they are employed to protect the infrastructure from lightning strikes. They have rapid response, are low maintenance, and do not appreciably degrade from use, making them virtually ideal devices for this application.

Semiconducting ceramics are also employed as gas sensors. When various gases are passed over a polycrystalline ceramic, its electrical resistance changes. With tuning to the possible gas mixtures, very inexpensive devices can be produced.

Superconductivity

Under some conditions, such as extremely low temperature, some ceramics exhibit high temperature superconductivity. The exact reason for this is not known, but there are two major families of superconducting ceramics.

Ferroelectricity and supersets

Piezoelectricity, a link between electrical and mechanical response, is exhibited by a large number of ceramic materials, including the quartz used to measure time in watches and other electronics. Such devices use both properties of piezoelectrics, using electricity to produce a mechanical motion (powering the device) and then using this mechanical motion to produce electricity (generating a signal). The unit of time measured is the natural interval required for electricity to be converted into mechanical energy and back again.

The piezoelectric effect is generally stronger in materials that also exhibit pyroelectricity, and all pyroelectric materials are also piezoelectric. These materials can be used to inter convert between thermal, mechanical, or electrical energy; for instance, after synthesis in a furnace, a pyroelectric crystal allowed to cool under no applied stress generally builds up a static charge of thousands of volts. Such materials are used in motion sensors, where the tiny rise in temperature from a warm body entering the room is enough to produce a measurable voltage in the crystal.

In turn, pyroelectricity is seen most strongly in materials which also display the ferroelectric effect, in which a stable electric dipole can be oriented or reversed by applying an electrostatic field. Pyroelectricity is also a necessary consequence of ferroelectricity. This can be used to store information in ferroelectric capacitors, elements of ferroelectric RAM.

The most common such materials are lead zirconate titanate and barium titanate. Aside from the uses mentioned above, their strong piezoelectric response is exploited in the design of high-frequency loudspeakers, transducers for sonar, and actuators for atomic force and scanning tunneling microscopes.

Positive thermal coefficient

Increases in temperature can cause grain boundaries to suddenly become insulating in some semiconducting ceramic materials, mostly mixtures of heavy metal titanates. The critical transition temperature can be adjusted over a wide range by variations in chemistry. In such materials, current will pass through the material until joule heating brings it to the transition temperature, at which point the circuit will be broken and current flow will cease. Such ceramics are used as self-controlled heating elements in, for example, the rear-window defrost circuits of automobiles.

At the transition temperature, the material's dielectric response becomes theoretically infinite. While a lack of temperature control would rule out any practical use of the material near its critical temperature, the dielectric effect remains exceptionally strong even at much higher temperatures. Titanates with critical temperatures far below room temperature have become synonymous with "ceramic" in the context of ceramic capacitors for just this reason.

Optical properties

Optically transparent materials focus on the response of a material to incoming lightwaves of a range of wavelengths. Frequency selective optical filters can be utilized to alter or enhance the brightness and contrast of a digital image. Guided lightwave transmission via frequency selective waveguides involves the emerging field of fiber optics and the ability of certain glassy compositions as a transmission medium for a range of frequencies simultaneously (multi-mode optical fiber) with little or no interference between competing wavelengths or frequencies. This resonant mode of energy and data transmission via electromagnetic (light) wave propagation, though low powered, is virtually lossless. Optical waveguides are used as components in Integrated optical circuits (e.g. light-emitting diodes, LEDs) or as the transmission medium in local and long haul optical communication systems. Also of value to the emerging materials scientist is the sensitivity of materials to radiation in the thermal infrared (IR) portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. This heat-seeking ability is responsible for such diverse optical phenomena as Night-vision and IR luminescence.

Thus, there is an increasing need in the military sector for high-strength, robust materials which have the capability to transmit light (electromagnetic waves) in the visible (0.4 – 0.7 micrometers) and mid-infrared (1 – 5 micrometers) regions of the spectrum. These materials are needed for applications requiring transparent armor, including next-generation high-speed missiles and pods, as well as protection against improvised explosive devices (IED).

In the 1960s, scientists at General Electric (GE) discovered that under the right manufacturing conditions, some ceramics, especially aluminium oxide (alumina), could be made translucent. These translucent materials were transparent enough to be used for containing the electrical plasma generated in high-pressure sodium street lamps. During the past two decades, additional types of transparent ceramics have been developed for applications such as nose cones for heat-seeking missiles, windows for fighter aircraft, and scintillation counters for computed tomography scanners.

In the early 1970s, Thomas Soules pioneered computer modeling of light transmission through translucent ceramic alumina. His model showed that microscopic pores in ceramic, mainly trapped at the junctions of microcrystalline grains, caused light to scatter and prevented true transparency. The volume fraction of these microscopic pores had to be less than 1% for high-quality optical transmission.

This is basically a particle size effect. Opacity results from the incoherent scattering of light at surfaces and interfaces. In addition to pores, most of the interfaces in a typical metal or ceramic object are in the form of grain boundaries which separate tiny regions of crystalline order. When the size of the scattering center (or grain boundary) is reduced below the size of the wavelength of the light being scattered, the scattering no longer occurs to any significant extent.

In the formation of polycrystalline materials (metals and ceramics) the size of the crystalline grains is determined largely by the size of the crystalline particles present in the raw material during formation (or pressing) of the object. Moreover, the size of the grain boundaries scales directly with particle size. Thus a reduction of the original particle size below the wavelength of visible light (~ 0.5 micrometers for shortwave violet) eliminates any light scattering, resulting in a transparent material.

Recently, Japanese scientists have developed techniques to produce ceramic parts that rival the transparency of traditional crystals (grown from a single seed) and exceed the fracture toughness of a single crystal. In particular, scientists at the Japanese firm Konoshima Ltd., a producer of ceramic construction materials and industrial chemicals, have been looking for markets for their transparent ceramics.

Livermore researchers realized that these ceramics might greatly benefit high-powered lasers used in the National Ignition Facility (NIF) Programs Directorate. In particular, a Livermore research team began to acquire advanced transparent ceramics from Konoshima to determine if they could meet the optical requirements needed for Livermore’s Solid-State Heat Capacity Laser (SSHCL). Livermore researchers have also been testing applications of these materials for applications such as advanced drivers for laser-driven fusion power plants.

Examples

Until the 1950s, the most important ceramic materials were (1) pottery, bricks and tiles, (2) cements and (3) glass. A composite material of ceramic and metal is known as cermet.

Other ceramic materials, generally requiring greater purity in their make-up than those above, include forms of several chemical compounds, including:

- Barium titanate (often mixed with strontium titanate) displays ferroelectricity, meaning that its mechanical, electrical, and thermal responses are coupled to one another and also history-dependent. It is widely used in electromechanical transducers, ceramic capacitors, and data storage elements. Grain boundary conditions can create PTC effects in heating elements.

- Bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide, a high-temperature superconductor

- Boron oxide is used in body armor.

- Boron nitride is structurally isoelectronic to carbon and takes on similar physical forms: a graphite-like one used as a lubricant, and a diamond-like one used as an abrasive.

- Earthenware used for domestic ware such as plates and mugs.

- Ferrite is used in the magnetic cores of electrical transformers and magnetic core memory.

- Lead zirconate titanate (PZT) was developed at the United States National Bureau of Standards in 1954. PZT is used as an ultrasonic transducer, as its piezoelectric properties greatly exceed those of Rochelle salt.[8]

- Magnesium diboride (MgB2) is an unconventional superconductor.

- Porcelain is used for a wide range of household and industrial products.

- Sialon (Silicon Aluminium Oxynitride) has high strength; resistance to thermal shock, chemical and wear resistance, and low density. These ceramics are used in non-ferrous molten metal handling, weld pins and the chemical industry.

- Silicon carbide (SiC) is used as a susceptor in microwave furnaces, a commonly used abrasive, and as a refractory material.

- Silicon nitride (Si3N4) is used as an abrasive powder.

- Steatite (magnesium silicates) is used as an electrical insulator.

- Titanium carbide Used in space shuttle re-entry shields and scratchproof watches.

- Uranium oxide (UO2), used as fuel in nuclear reactors.

- Yttrium barium copper oxide (YBa2Cu3O7-x), another high temperature superconductor.

- Zinc oxide (ZnO), which is a semiconductor, and used in the construction of varistors.

- Zirconium dioxide (zirconia), which in pure form undergoes many phase changes between room temperature and practical sintering temperatures, can be chemically "stabilized" in several different forms. Its high oxygen ion conductivity recommends it for use in fuel cells and automotive oxygen sensors. In another variant, metastable structures can impart transformation toughening for mechanical applications; most ceramic knife blades are made of this material.

- Partially stabilised zirconia (PSZ) is much less brittle than other ceramics and is used for metal forming tools, valves and liners, abrasive slurries, kitchen knives and bearings subject to severe abrasion.[9]

Ceramic products

By usage

For convenience, ceramic products are usually divided into four main types; these are shown below with some examples:

- Structural, including bricks, pipes, floor and roof tiles

- Refractories, such as kiln linings, gas fire radiants, steel and glass making crucibles

- Whitewares, including tableware, cookware, wall tiles, pottery products and sanitary ware[10]

- Technical, also known as engineering, advanced, special, and fine ceramics. Such items include:

- gas burner nozzles

- ballistic protection

- nuclear fuel uranium oxide pellets

- biomedical implants

- coatings of jet engine turbine blades

- ceramic disk brake

- missile nose cones

- bearing (mechanical)

- tiles used in the Space Shuttle program

Ceramics made with clay

Frequently, the raw materials of modern ceramics do not include clays.[11] Those that do are classified as follows:

- Earthenware, fired at lower temperatures than other types

- Stoneware, vitreous or semi-vitreous

- Porcelain, which contains a high content of kaolin

- Bone china

Classification of technical ceramics

Technical ceramics can also be classified into three distinct material categories:

- Oxides: alumina, beryllia, ceria, zirconia

- Nonoxides: carbide, boride, nitride, silicide

- Composite materials: particulate reinforced, fiber reinforced, combinations of oxides and nonoxides.

Each one of these classes can develop unique material properties because ceramics tend to be crystalline.

Applications

- Knife blades: the blade of a ceramic knife will stay sharp for much longer than that of a steel knife, although it is more brittle and can snap from a fall onto a hard surface.

- Carbon-ceramic brake disks for vehicles are resistant to brake fade at high temperatures.

- Advanced composite ceramic and metal matrices have been designed for most modern armoured fighting vehicles because they offer superior penetrating resistance against shaped charges (such as HEAT rounds) and kinetic energy penetrators.

- Ceramics such as alumina and boron carbide have been used in ballistic armored vests to repel large-caliber rifle fire. Such plates are known commonly as small arms protective inserts, or SAPIs. Similar material is used to protect the cockpits of some military airplanes, because of the low weight of the material.

- Ceramics can be used in place of steel for ball bearings. Their higher hardness means they are much less susceptible to wear and typically last for triple the lifetime of a steel part. They also deform less under load, meaning they have less contact with the bearing retainer walls and can roll faster. In very high speed applications, heat from friction during rolling can cause problems for metal bearings, which are reduced by the use of ceramics. Ceramics are also more chemically resistant and can be used in wet environments where steel bearings would rust. In some cases, their electricity-insulating properties may also be valuable in bearings. Two drawbacks to ceramic bearings are a significantly higher cost and susceptibility to damage under shock loads.

- In the early 1980s, Toyota researched production of an adiabatic engine using ceramic components in the hot gas area. The ceramics would have allowed temperatures of over 3000 °F (1650 °C). The expected advantages would have been lighter materials and a smaller cooling system (or no need for one at all), leading to a major weight reduction. The expected increase of fuel efficiency of the engine (caused by the higher temperature, as shown by Carnot's theorem) could not be verified experimentally; it was found that the heat transfer on the hot ceramic cylinder walls was higher than the transfer to a cooler metal wall as the cooler gas film on the metal surface works as a thermal insulator. Thus, despite all of these desirable properties, such engines have not succeeded in production because of costs for the ceramic components and the limited advantages. (Small imperfections in the ceramic material with its low fracture toughness lead to cracks, which can lead to potentially dangerous equipment failure.) Such engines are possible in laboratory settings, but mass production is not feasible with current technology.

- Work is being done in developing ceramic parts for gas turbine engines. Currently, even blades made of advanced metal alloys used in the engines' hot section require cooling and careful limiting of operating temperatures. Turbine engines made with ceramics could operate more efficiently, giving aircraft greater range and payload for a set amount of fuel.

- Recent advances have been made in ceramics which include bioceramics, such as dental implants and synthetic bones. Hydroxyapatite, the natural mineral component of bone, has been made synthetically from a number of biological and chemical sources and can be formed into ceramic materials. Orthopedic implants coated with these materials bond readily to bone and other tissues in the body without rejection or inflammatory reactions so are of great interest for gene delivery and tissue engineering scaffolds. Most hydroxyapatite ceramics are very porous and lack mechanical strength, and are used to coat metal orthopedic devices to aid in forming a bond to bone or as bone fillers. They are also used as fillers for orthopedic plastic screws to aid in reducing the inflammation and increase absorption of these plastic materials. Work is being done to make strong, fully dense nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite ceramic materials for orthopedic weight bearing devices, replacing foreign metal and plastic orthopedic materials with a synthetic, but naturally occurring, bone mineral. Ultimately, these ceramic materials may be used as bone replacements or with the incorporation of protein collagens, synthetic bones.

- High-tech ceramic is used in watchmaking for producing watch cases. The material is valued by watchmakers for its light weight, scratch resistance, durability and smooth touch. IWC is one of the brands that initiated the use of ceramic in watchmaking.[12]

Ceramics in archaeology

Ceramic artifacts have an important role in archaeology for understanding the culture, technology and behavior of peoples of the past. They are among the most common artifacts to be found at an archaeological site, generally in the form of small fragments of broken pottery called sherds. Processing of collected sherds can be consistent with two main types of analysis: technical and traditional.

Traditional analysis involves sorting ceramic artifacts, sherds and larger fragments into specific types based on style, composition, manufacturing and morphology. By creating these typologies it is possible to distinguish between different cultural styles, the purpose of the ceramic and technological state of the people among other conclusions. In addition, by looking at stylistic changes of ceramics over time is it possible to separate (seriate) the ceramics into distinct diagnostic groups (assemblages). A comparison of ceramic artifacts with known dated assemblages allows for a chronological assignment of these pieces.[13]

The technical approach to ceramic analysis involves a finer examination of the composition of ceramic artifacts and sherds to determine the source of the material and through this the possible manufacturing site. Key criteria are the composition of the clay and the temper used in the manufacture of the article under study: temper is a material added to the clay during the initial production stage, and it is used to aid the subsequent drying process. Types of temper include shell pieces, granite fragments and ground sherd pieces called 'grog'. Temper is usually identified by microscopic examination of the temper material. Clay identification is determined by a process of refiring the ceramic, and assigning a color to it using Munsell Soil Color notation. By estimating both the clay and temper compositions, and locating a region where both are known to occur, an assignment of the material source can be made. From the source assignment of the artifact further investigations can be made into the site of manufacture.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Involving no metallic bonding, and so not having metallic properties as a material.

References

- ↑ Black, J. T.; Kohser, R. A. (2012). DeGarmo's materials and processes in manufacturing. Wiley. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-470-92467-9.

- ↑ Carter, C. B.; Norton, M. G. (2007). Ceramic materials: Science and engineering. Springer. pp. 3 & 4. ISBN 978-0-387-46271-4.

- ↑ Carter, C. B.; Norton, M. G. (2007). Ceramic materials: Science and engineering. Springer. pp. 20 & 21. ISBN 978-0-387-46271-4.

- ↑ κεραμικός, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ κέραμος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages

- ↑ "ceramic". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Wachtman, John B., Jr. (ed.) (1999) Ceramic Innovations in the 20th century, The American Ceramic Society. ISBN 978-1-57498-093-6.

- ↑ Garvie, R. C.; Hannink, R. H.; Pascoe, R. T. (1975). "Ceramic steel?". Nature. 258 (5537): 703–704. Bibcode:1975Natur.258..703G. doi:10.1038/258703a0.

- ↑ "Whiteware Pottery". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Geiger, Greg. Introduction To Ceramics, American Ceramic Society

- ↑ Ceramic in Watchmaking. Watches.infoniac.com (2008-01-09). Retrieved on 2011-11-28.

- ↑ Mississippi Valley Archaeological Center, Ceramic Analysis Archived June 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine., Retrieved 04-11-12

Further reading

- Guy, John (1986). Guy, John, ed. Oriental trade ceramics in South-East Asia, ninth to sixteenth centuries: with a catalogue of Chinese, Vietnamese and Thai wares in Australian collections (illustrated, revised ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

External links

- Dolni Vestonice Venus- Oldest known Ceramic statuette of a nude female figure dated to 29 000 – 25 000 BP (Gravettian industry. Czech Republic

- The Gardiner Museum – The only museum in Canada entirely devoted to ceramics

- Introduction, Scientific Principles, Properties and Processing of Ceramics

- Advanced Ceramics – The Evolution, Classification, Properties, Production, Firing, Finishing and Design of Advanced Ceramics

- Cerame-Unie, aisbl – The European Ceramic Industry Association