Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

| Prince Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord ONLH, OSE | |

|---|---|

|

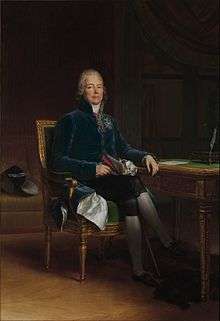

Portrait of Talleyrand, by Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (1809). | |

| 1st Prime Minister of France | |

|

In office 9 July 1815 – 26 September 1815 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVIII |

| Succeeded by | Armand-Emmanuel de Vignerot du Plessis |

| French Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

|

In office 9 July 1815 – 26 September 1815 | |

| Preceded by | Louis Pierre Edouard |

| Succeeded by | Armand-Emmanuel de Vignerot du Plessis |

|

In office 13 May 1814 – 20 March 1815 | |

| Preceded by | Antoine René Charles Mathurin |

| Succeeded by | Armand Augustin Louis de Caulaincourt |

|

In office 22 November 1799 – 9 August 1807 | |

| Preceded by | Charles-Frédéric Reinhard |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Baptiste de Nompère de Champagny |

|

In office 15 July 1797 – 20 July 1799 | |

| Preceded by | Charles-François Delacroix |

| Succeeded by | Charles-Frédéric Reinhard |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

2 February 1754* Paris, France |

| Died |

17 May 1838 (aged 84) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Political party |

Jacobin (1789–1792) Maraisard (1792–1795) Thermidorian (1795–1799) Bonapartist (1797–1814) Legitimist (1814–1830) Orléanist (1830–1838) |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine Grand (m. 1802–34); her death |

| Children |

None (official); probably three illegitimate children:

|

| Alma mater | Lycée Saint-Louis |

| Profession | Bishop (ex), diplomat |

| Religion | Catholic Church |

| Signature |

|

| *Encyclopedia of World Biography and Catholic Encyclopedia give 13 February | |

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (/ˈtæləˌrænd ˈpɛrɪˌɡɔːr/;[1] French: [ʃaʁl moʁis də tal(ɛ)ʁɑ̃ peʁiɡɔʁ]; 1754–1838), prince de Bénévent, then prince de Talleyrand, was a laicized French bishop, politician, and diplomat. After theology studies, he became in 1780 Agent-General of the Clergy and represented the Catholic Church to the French Crown. He worked at the highest levels of successive French governments, most commonly as foreign minister or in some other diplomatic capacity. His career spanned the regimes of Louis XVI, the years of the French Revolution, Napoleon, Louis XVIII, and Louis-Philippe. Those he served often distrusted Talleyrand but, like Napoleon, found him extremely useful. The name "Talleyrand" has become a byword for crafty, cynical diplomacy.

He was Napoleon's chief diplomat during the years when French military victories brought one European state after another under French hegemony. However, most of the time, Talleyrand worked for peace so as to consolidate France's gains. He succeeded in obtaining peace with Austria through the 1801 Treaty of Luneville and with Britain in the 1802 Treaty of Amiens. He could not prevent the renewal of war in 1803 but by 1805, he opposed his emperor's renewed wars against Austria, Prussia, and Russia. He resigned as foreign minister in August 1807, but retained the trust of Napoleon and conspired to undermine the emperor's plans through secret dealings with Tsar Alexander of Russia and Austrian minister Metternich. Talleyrand sought a negotiated secure peace so as to perpetuate the gains of the French revolution. Napoleon rejected peace and when he fell in 1814, Talleyrand took charge of the Bourbon restoration based on the principle of legitimacy. He played a major role at the Congress of Vienna in 1814–1815, where he negotiated a favourable settlement for France while undoing Napoleon's conquests.

Talleyrand polarizes scholarly opinion. Some regard him as one of the most versatile, skilled and influential diplomats in European history, and some believe that he was a traitor, betraying in turn the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution, Napoleon, and the Restoration.

Early life

Talleyrand was born into a leading aristocratic family in Paris. His father, Count Daniel de Talleyrand-Périgord, was 20 years of age when Charles was born. His mother was Alexandrine de Damas d'Antigny. Both his parents held positions at court, but as cadets of their respective families, had no important income. From childhood, Talleyrand walked with a limp. In his Memoirs, he linked this infirmity to an accident at age four which made him unable to enter the expected military career and caused him to be called later le diable boiteux[2] (French for "the lame devil") among other nicknames. However, recent research has shown that his limp was in fact congenital.[3] Talleyrand's father had a long career in the Army, reaching the rank of lieutenant general, as did his uncle, Gabriel Marie de Périgord, despite having the same infirmity. The choice of a career in the Church for Charles-Maurice was aimed at having him succeed his uncle Alexandre Angélique de Talleyrand-Périgord, then Archbishop of Reims, one of the richest and most prestigious dioceses in France.[4] It would appear that the family, though ancient and illustrious, was not particularly prosperous, and saw Church positions as a path to wealth. Talleyrand attended the Collège d'Harcourt, the seminary of Saint-Sulpice,[5] while studying theology at the Sorbonne until the age of 21. He was ordained a priest in 1779, at the age of 25. In 1780, he became Agent-General of the Clergy, a representative of the Catholic Church to the French Crown. In this important position, he was instrumental in drafting a general inventory of Church properties in France as of 1785, along with a defence of "inalienable rights of the Church", a stance he was later to deny. In 1789, the influence of Talleyrand's father and family overcame the King's dislike and obtained his appointment as Bishop of Autun. The undoubtedly able Talleyrand, though free-thinking in the Enlightenment mould, appears at the time to have been outwardly respectful of religious observance. In the course of the Revolution, however, he was to manifest his cynicism and abandon all orthodox Catholic practice. In 1801, Pope Pius VII laicized Talleyrand, an event most uncommon at the time in the history of the Church.[6]

French Revolution

Shortly after he was ordained as Bishop of Autun, Talleyrand attended the Estates-General of 1789, representing the clergy, the First Estate. During the French Revolution, Talleyrand strongly supported the anti-clericalism of the revolutionaries. He assisted Mirabeau in the appropriation of Church properties. He participated in the writing of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and proposed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy that nationalised the Church, and swore in the first four constitutional bishops, even though he had himself resigned as Bishop following his excommunication by Pope Pius VI in 1791. During the Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790, Talleyrand celebrated Mass. Notably, he promoted public education in full spirit of the Enlightenment by preparing a 216-page Report on Public Instruction. It proposed pyramidical structure rising through local, district, and departmental schools, and parts were later adopted.[7]

In 1792, he was sent twice, though unofficially, to Britain to avert war. Besides an initial declaration of neutrality during the first campaigns of 1792, his mission ultimately failed. In September 1792, he left Paris for England just at the beginning of the September massacres, yet declined to defect. The National Convention issued a warrant for his arrest in December 1792. In March 1794, he was forced to leave the country by Pitt's expulsion order. He then went to the neutral country of the United States where he stayed until his return to France in 1796. During his stay, he supported himself by working as a bank agent, involved in commodity trading and real estate speculation. He was the house guest of Aaron Burr of New York and collaborated with Theophile Cazenove, who lived at Market Street, Philadelphia.[8] Talleyrand years later refused the same generosity to Burr because Talleyrand had been friends with Alexander Hamilton, whom Burr had killed in a duel.

After 9 Thermidor, he mobilised his friends (most notably the abbé Martial Borye Desrenaudes and Germaine de Staël) to lobby in the National Convention and then the newly established Directoire for his return. His name was then suppressed from the émigré list and he returned to France on 25 September 1796. In 1797, he became Foreign Minister. He was behind the demand for bribes in the XYZ Affair which escalated into the Quasi-War, an undeclared naval war with America, 1798–99. Talleyrand saw a possible political career for Napoleon during the Italian campaigns of 1796 to 1797. He wrote many letters to Napoleon, and the two became close allies. Talleyrand was against the destruction of the Republic of Venice, but he complimented Napoleon when peace with Austria was concluded (Venice was given to Austria), probably because he wanted to reinforce his alliance with Napoleon.

Consulate

Together with Napoleon's younger brother, Lucien Bonaparte, he was instrumental in the 1799 coup d'état of 18 Brumaire, establishing the French Consulate government. Soon after he was made Foreign Minister by Napoleon, although he rarely agreed with Napoleon's foreign policy. The Pope also released him from the ban of excommunication in the Concordat of 1801, which also revoked the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Talleyrand was instrumental in the completion of the Treaty of Amiens in 1802. He wanted Napoleon to keep peace afterwards, as he thought France had reached its maximum expansion.

Talleyrand was an integral player in the German mediatization. While the Treaty of Campo Formio had, on paper, stripped German princes of their lands beyond the left bank of the Rhine, it was not until the Treaty of Lunéville that this was enforced. The French annexed these lands and it was deemed proper that the deposed sovereigns receive new territories on the Right Bank of the Rhine. As many of these rulers gave out bribes in order to secure new lands Talleyrand became quite wealthy. He gained an estimated 10 million francs in the process. This was the first blow in the destruction of the Holy Roman Empire.[9]

Napoleon forced his hand into marriage in September 1802 to longtime mistress Catherine Grand (née Worlée). Talleyrand purchased the Château de Valençay in May 1803, upon the urging of Napoleon. This would later be the site of the imprisonment of the Spanish Royalty in 1808–1813, after Napoleon's invasion of Spain.

French Empire

In May 1804, Napoleon bestowed upon him the title of Grand Chamberlain of the Empire. In 1806, he was made Sovereign Prince of Benevento (or Bénévent), a former papal fief in southern Italy. Talleyrand held the title till 1815 and administered the principality concurrently with his other tasks.[10]

Talleyrand was opposed to the harsh treatment of Austria in the 1805 Treaty of Pressburg and of Prussia in the Peace of Tilsit in 1807. In 1806, after Pressburg and just as in 1803, he profited greatly from the reorganization of the German lands, this time into the Confederation of the Rhine. He was then shut out completely from the negotiations at Tilsit. After she famously failed imploring of Napoleon to spare her nation, Queen Louise of Prussia wept and was consoled by Talleyrand. This gave him a good name among the elites of the European countries outside France.

Talleyrand breaks with Napoleon

Having wearied of serving a master in whom he no longer had much confidence, Talleyrand resigned as minister of foreign affairs in 1807, although the Emperor retained him in the Council of State. He disapproved of Napoleon's Spanish initiative, which resulted in the Peninsular War beginning in 1808. At the Congress of Erfurt in September–October 1808, Talleyrand secretly counseled Tsar Alexander. The Tsar's attitude towards Napoleon was one of apprehensive opposition. Talleyrand repaired the confidence of the Russian monarch, who rebuked Napoleon's attempts to form a direct anti-Austrian military alliance. Napoleon had expected Talleyrand to help convince the Tsar to accept his proposals and never discovered that Talleyrand was working at cross-purposes. Talleyrand believed Napoleon would eventually destroy the empire he had worked to build across multiple rulers.[11]

After his resignation in 1807 from the ministry, Talleyrand began to accept bribes from hostile powers (mainly Austria, but also Russia), to betray Napoleon's secrets.[12] Talleyrand and Joseph Fouché, who were typically enemies in both politics and the salons, had a rapprochement in late 1808 and entered into discussions over the imperial line of succession. Napoleon had yet to address this matter and the two men knew that without a legitimate heir a struggle for power would erupt in the wake of Napoleon's death. Even Talleyrand, who believed that Napoleon's policies were leading France to ruin, understood the necessity of peaceful transitions of power. Napoleon received word of their actions and deemed them treasonous. This perception caused the famous dressing down of Talleyrand in front of Napoleon's marshals, during which Napoleon famously claimed that he could "break him like a glass, but it's not worth the trouble" and added with a scatological tone that Talleyrand was "shit in a silk stocking",[13] to which the minister coldly retorted, once Napoleon had left, "Pity that so great a man should have been so badly brought up!"

Talleyrand opposed the further harsh treatment of Austria in 1809 after the War of the Fifth Coalition. He was also a critic of the French invasion of Russia in 1812. He was invited to resume his former office in late 1813, but Talleyrand could see that power was slipping from Napoleon's hands. On 1 April 1814 he led the French Senate in establishing a provisional government in Paris, of which he was elected president. On 2 April the Senate officially deposed Napoleon with the Acte de déchéance de l'Empereur; by 11 April it had approved the Treaty of Fontainebleau and adopted a new constitution to re-establish the Bourbon monarchy.

Bourbon Restoration

When Napoleon was succeeded by Louis XVIII in April 1814, Talleyrand was one of the key agents of the restoration of the House of Bourbon, although he opposed the new legislation of Louis' rule. Talleyrand was the chief French negotiator at the Congress of Vienna, and, in that same year, he signed the Treaty of Paris. It was due in part to his skills that the terms of the treaty were remarkably lenient towards France. As the Congress opened, the right to make decisions was restricted to four countries: Austria, the United Kingdom, Prussia, and Russia. France and other European countries were invited to attend, but were not allowed to influence the process. Talleyrand promptly became the champion of the small countries and demanded admission into the ranks of the decision-making process. The four powers admitted France and Spain to the decision-making backrooms of the conference after a good deal of diplomatic maneuvering by Talleyrand, who had the support of the Spanish representative, Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador. Spain was excluded after a while (a result of both the Marquis of Labrador's incompetence as well as the quixotic nature of Spain's agenda), but France (Talleyrand) was allowed to participate until the end. Russia and Prussia sought to enlarge their territory at the Congress. Russia demanded annexation of Poland (already occupied by Russian troops), and this demand was finally satisfied, despite protests by France, Austria and the United Kingdom. Austria was afraid of future conflicts with Russia or Prussia and the United Kingdom was opposed to their expansion as well – and Talleyrand managed to take advantage of these contradictions within the former anti-French coalition. On 3 January 1815, a secret treaty was signed by France's Talleyrand, Austria's Metternich and Britain's Castlereagh. By this tract, officially a secret treaty of defensive alliance,[14] the three powers agreed to use force if necessary to "repulse aggression" (of Russia and Prussia) and to protect the "state of security and independence". This agreement effectively spelled the end of the anti-France coalition.

Talleyrand, having managed to establish a middle position, received some favours from the other countries in exchange for his support: France returned to its 1792 boundaries without reparations, with French control over papal Avignon, Montbéliard (Mompelgard) and Salm, which had been independent at the start of the French Revolution in 1789. It would later be debated which outcome would have been better for France: allowing Prussia to annex all of Saxony (Talleyrand ensured that only part of the kingdom would be annexed) or the Rhine provinces. The first option would have kept Prussia farther away from France, but would have needed much more opposition as well. Some historians have argued that Talleyrand's diplomacy wound up establishing the faultlines of World War I, especially as it allowed Prussia to engulf small German states west of the Rhine. This simultaneously placed Prussian armed forces at the French-German frontier, for the first time; made Prussia the largest German power in terms of territory, population and the industry of the Ruhr and Rhineland; and eventually helped pave the way to German unification under the Prussian throne. However, at the time Talleyrand's diplomacy was regarded as successful, as it removed the threat of France being partitioned by the victors. Talleyrand also managed to strengthen his own position in France (ultraroyalists had disapproved of the presence of a former "revolutionary" and "murderer of the Duke d'Enghien" in the royal cabinet).

Napoleon's return to France in 1815 and his subsequent defeat, the Hundred Days, was a reverse for the diplomatic victories of Talleyrand; the second peace settlement was markedly less lenient and it was fortunate for France that the business of the Congress had been concluded. Talleyrand resigned in September of that year, either over the second treaty or under pressure from opponents in France. For the next fifteen years he restricted himself to the role of "elder statesman", criticising—and intriguing—from the sidelines. However, when King Louis-Philippe came to power in the July Revolution of 1830, Talleyrand agreed to become ambassador to the United Kingdom, a post he held from 1830 to 1834. In this role, he strove to reinforce the legitimacy of Louis-Philippe's regime, and proposed a partition plan for the newly independent Belgium.

Private life

Talleyrand had a reputation as a voluptuary and a womaniser. He left no legitimate children, though he may have fathered illegitimate ones. Four possible children of his have been identified: Charles Joseph, comte de Flahaut, generally accepted to be an illegitimate son of Talleyrand; the painter Eugène Delacroix, once rumoured to be Talleyrand's son, though this is doubted by historians who have examined the issue (for example, Léon Noël, French ambassador); the "Mysterious Charlotte", possibly his daughter by his future wife, Catherine Worlée Grand; and Pauline, ostensibly the daughter of the Duke and Duchess Dino. Of these four, only the first is given credence by historians. However, the French historian Emmanuel de Waresquiel has lately given much credibility to father-daughter link between Talleyrand and Pauline who he referred to as "my dear Minette".

Aristocratic women were a key component of Talleyrand's political tactics, both for their influence and their ability to cross borders unhindered. His presumed lover Germaine de Staël was a major influence on him, and he on her. Though their personal philosophies were most different (she a romantic, he very much unsentimental), she assisted him greatly, most notably by lobbying Barras to permit Talleyrand to return to France from his American exile, and then to have him made foreign minister. He lived with Catherine Worlée, born in India and married there to Charles Grand. She had traveled about before settling in Paris in the 1780s, where she lived as a notorious courtesan for several years before divorcing Grand to marry Talleyrand. Talleyrand was in no hurry to marry, and it was after repeated postponements that Napoleon obliged him in 1802 to formalize the relationship or risk his political career. After her death in 1834, Talleyrand lived with Dorothea von Biron, the divorced wife of his nephew, the Duke of Dino.

Talleyrand's venality was celebrated; in the tradition of the ancien régime, he expected to be paid for the state duties he performed—whether these can properly be called "bribes" is open to debate. For example, during the German Mediatisation, the consolidation of the small German states, a number of German rulers and elites paid him to save their possessions or enlarge their territories. Less successfully, he solicited payments from the United States government to open negotiations, precipitating a diplomatic disaster (the "XYZ Affair"). The difference between his diplomatic success in Europe and failure with the United States illustrates that his diplomacy rested firmly on the power of the French army that was a terrible threat to the German states within reach, but lacked the logistics to threaten the USA not the least because of the Royal Navy domination of the seas. After Napoleon's defeat, he withdrew claims to the title "Prince of Benevento", but was created Duke of Talleyrand with the style "Prince de Talleyrand" for life, in the same manner as his estranged wife.[15]

Described by biographer Philip Ziegler as a "pattern of subtlety and finesse" and a "creature of grandeur and guile",[16] Talleyrand was a great conversationalist, gourmet, and wine connoisseur. From 1801 to 1804, he owned Château Haut-Brion in Bordeaux. He employed the renowned French chef Carême, one of the first celebrity chefs known as the "chef of kings and king of chefs", and was said to have spent an hour every day with him.[17] His Paris residence on the Place de la Concorde, acquired in 1812 and sold to James Mayer de Rothschild in 1838, is now owned by the Embassy of the United States.

Talleyrand has been regarded as a traitor because of his support for successive regimes, some of which were mutually hostile. According to French philosopher Simone Weil, criticism of his loyalty is unfounded, as Talleyrand served not every regime as had been said, but in reality "France behind every regime".[18]

Near the end of his life, Talleyrand became interested in Catholicism again while teaching his young granddaughter simple prayers. The Abbé Félix Dupanloup came to Talleyrand in his last hours, and according to his account Talleyrand made confession and received extreme unction. When the abbé tried to anoint Talleyrand's palms, as prescribed by the rite, he turned his hands over to make the priest anoint him on the back of the hands, since he was a bishop. He also signed, in the abbé's presence, a solemn declaration in which he openly disavowed "the great errors which . . . had troubled and afflicted the Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Church, and in which he himself had had the misfortune to fall." He died on 17 May 1838 and was buried in Notre-Dame Chapel,[19] near his Castle of Valençay.

Today, when speaking of the art of diplomacy, the phrase "he is a Talleyrand" is used to describe a statesman of great resourcefulness and craft.[20]

Honours

- Pair de France. [21]

- Knight Grand Cross in the Legion of Honour[22]

- Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece[23]

- Knight Grand Cross in the Order of St. Stephen of Hungary.[24]

- Knight Grand Cross in the Order of Saint Andrew.[25]

- Knight Grand Cross in the Order of the Red Eagle.[26]

- Knight Grand Cross in the Order of the Black Eagle.[27]

- Knight of the Order of the Elephant.[28]

- Knight of the Order of Saint Hubert.[29]

- Knight Grand Cross in the Order of the Sun.[30]

- Knight Grand Cross in the Order of the crown of saxen.[31]

Anecdotes

- In 1797 a rumor spread that the King of Great Britain had died. A banker, hoping to make a profit from inside information, appeared at Talleyrand's door seeking information. Talleyrand replied along the lines of, "But of course. I shall be delighted, if the information I have to give be of any use to you." The banker listened with bated breath as Talleyrand continued: "Some say the King of England is dead; others, that he is not dead: for my own part, I believe neither the one nor the other. I tell you this in confidence, but I rely on your discretion."

- The Spanish Ambassador complained to Talleyrand that the seals on his diplomatic letters had been broken. Talleyrand replied, "I shall wager I can guess how the thing happened. I am convinced your despatch was opened by some one who desired to know what was inside."

- Germaine de Staël's novel Delphine allegedly depicted Talleyrand as an old woman, and herself as the heroine. Upon meeting Madame de Staël, Talleyrand remarked, "They tell me that we are both of us in your novel, in the disguise of women."[32]

- Talleyrand had a morbid dread of falling out of bed in his sleep. To prevent this, he had his mattresses made with a depression in the centre. As a further safety measure, he wore fourteen cotton nightcaps at once, held together by 'a sort of tiara'.[33]

- Following the arrival of the Allies, Talleyrand's mansion hosted Tsar Alexander. Later, his bedroom became the center of government in the provisional government. It was actually quite common to hold important occurrences in one's bedroom as it was warm for the host while the attendants had to stand in the cold night air.

- On hearing of the death of a Turkish ambassador, Talleyrand is supposed to have said: "I wonder what he meant by that?" More commonly, the quote is attributed to Metternich, the Austrian diplomat, upon Talleyrand's death in 1838.[34]

- During the occupation of Paris by the Allies, Prussian General Blücher wanted to destroy the Pont d'Iéna, which was named after a French victorious battle against Prussia. The Prefect of Paris tried everything to change the mind of Blücher, without success, and finally went to Talleyrand asking him whether he could write a letter to the General asking him not to destroy the bridge. Talleyrand instead wrote to Tsar Alexander, who was in person in Paris, asking him to grant to the people of Paris the favour of inaugurating himself the bridge under a new name (Pont de l'École militaire). The Tsar accepted, and Blücher could not then destroy a bridge inaugurated by an Ally. The name of the bridge was reverted to its original name under Louis-Philippe.

- The district of East Levenshulme in Manchester is called Talleyrand. There is a local tradition that he stayed there, presumably during 1792–94.

In fiction

- Talleyrand is portrayed in Dennis Wheatley's series of novels featuring secret agent and gallant Roger Brook (also M.Chevalier de Breuc).

- Talleyrand was featured in the two-character theatre piece by Jean-Claude Brisville Supping with the Devil, in which he is depicted dining with Joseph Fouché while deciding how to preserve their respective power under the coming regime. The drama was hugely successful and was turned into the movie Le Souper (1992), directed by Edouard Molinaro, starring Claude Rich and Claude Brasseur.

- Talleyrand was also a major supporting character in Katherine Neville's book The Eight, a quasi-mystical adventure novel about a centuries-long struggle for control of a chess set with mysterious powers.

- Talleyrand plays a significant part in Arthur Conan Doyle's story "How the Brigadier Slew the Brothers of Ajaccio" (1895), part of the Brigadier Gerard series.

- Talleyrand appears as a supporting character in Rudyard Kipling's short story "A Priest in Spite of Himself", collected in Rewards and Fairies, 1910.

- Talleyrand is the central figure in Roberto Calasso's epic "The Ruin of Kasch". As Italo Calvino noted in 'Panorama Mese', the book "takes up two subjects: the first is Talleyrand, and the second is everything else."[35]

- Talleyrand appears as a character in the 1934 novel Captain Caution, by Kenneth Roberts.

- Talleyrand is the subject of "The Third Lion" by author Floyd Kemske.

- Talleyrand is an offstage but influential character near the end of The Surgeon's Mate, one of the 20 books in the Aubrey-Maturin series of seafaring novels by Patrick O'Brian.

- He appears in Naomi Novik's fifth Temeraire novel, Victory of Eagles.

- He is a supporting character in the BBC Books Doctor Who novel World Game.

- Talleyrand is the central figure in R.G. Waldecks novel "Lustre in the Sky" 1946

- Talleyrand is portrayed by Malcolm Keen in the Count of Monte Cristo (TV series) – Episode 22 of 39: The Talleyrand Affair (1955)

In popular culture

- In 1995, then Prime Minister of Australia Paul Keating compared then Australian Leader of the Opposition John Howard regaining the Liberal leadership to Talleyrand.

- " ..... Here he is (John Howard) politically limping in like the Bishop of Autun, the Talleyrand of the Liberal Party, scraping his way back into Australian history." 2 February 1995

- "Talleyrand" is the pen-name of a satirical columnist in The University Observer.

- Sacha Guitry played Talleyrand in his 1948 film The Lame Devil (Le Diable boiteux), a fictionalized account of Talleyrand's life. He later reprised the role in the 1955 film Napoléon.

- In 1993 film The Three Musketeers, Cardinal de Richelieu says to Queen Anne: Remember, Kings come and Kings go but one thing remains the same. And that is me., a sentence inspired by the saying "Regimes may fall and fail, but I do not", attributed to Talleyrand.

- Talleyrand was played by John Malkovich in the TV mini-series Napoléon from 2002. For his performance John Malkovich was nominated for an Emmy in 2003 as "Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or a Movie".

- In the RTS game Rise of Nations, Talleyrand is featured as a bonus card for the French nation. He has the ability to force an alliance or declare war for one turn.

Gallery

.svg.png) Arms of Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

Arms of Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord.svg.png) Arms of Talleyrand under the Napoleonic Empire

Arms of Talleyrand under the Napoleonic Empire

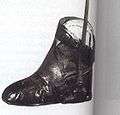

Photograph of the famed orthopedic shoe of Charles-Maurice Talleyrand-Périgord. Today located in the Chateau de Valencay.

Photograph of the famed orthopedic shoe of Charles-Maurice Talleyrand-Périgord. Today located in the Chateau de Valencay. Inscription at the Hôtel de Saint-Florentin

Inscription at the Hôtel de Saint-Florentin

Notes

- ↑ "Talleyrand-Périgord". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ Royot, Daniel (2007). Divided Loyalties in a Doomed Empire. University of Delaware Press, ISBN 978-0-87413-968-6, p. 138: "Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord was the essence of the metamorphic talent inherent in French aristocracy. The so-called Diable boiteux (lame devil), born in 1754 was not fit for armed service."

- ↑ Emmanuel de Waresquiel, Talleyrand. Le prince immobile, Paris, Fayard, 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Emmanuel de Waresquiel, op. cit., p. 31.

- ↑ "il est admis, ... en 1770, au grand séminaire de Saint-Sulpice": http://www.talleyrand.org

- ↑ Controversial concordats. Catholic University of America Press. 1999.

- ↑ . Samuel F. Scott and Barry Rothaus, eds., Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution 1789–1799 (vol. 2 1985), pp 928–32, online

- ↑ "Full text of "Cazenove journal, 1794 : a record of the journey of Theophile Cazenove through New Jersey and Pennsylvania"". Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Palmer, Robert Roswell; Joel Colton (1995). A History of the Modern World (8 ed.). New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 419. ISBN 978-0-67943-253-1.

- ↑ Duff Cooper: Talleyrand, Frankfurt 1982. ISBN 3-458-32097-0

- ↑ Haine, Scott. The History of France (1st ed.). Greenwood Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-313-30328-2. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - ↑ Lawday, David (2007). Napoleon's Master: A Life of Prince Talleyrand. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-37297-3.

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/reviews/talleyrand-napoleons-master-by-david-lawday-424034.html

- ↑ Traité sécret d'alliance défensive, conclu à Vienne entre Autriche, la Grande bretagne et la France, contre la Russie et la Prussie, le 3 janvier 1815

- ↑ Bernard, p. 266, 368 fn.

- ↑ The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace, and the Course of History by Philip Bobbitt (2002), chp 21

- ↑ J.A.Gere and John Sparrow (ed.), Geoffrey Madan's Notebooks, Oxford University Press, 1981, at page 12

- ↑ Simone Weil (2002). The Need for Roots. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 0-415-27102-9.

- ↑ Talleyrand's short biography in Napoleon & Empire website, displaying photographs of his castle of Valençay and of his tomb

- ↑

- Gérard Robichaud, Papa Martel, University of Maine Press, 2003, p.125.

- Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), H.M. Stationery Off., 1964, p.1391

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ Verslag der handelingen der Staten-Generaal, Deel 2. p 26

- ↑ On me dit que nous sommes tous les deux dans votre roman, déguisés en femme.

- ↑ André Castelot (1980), Talleyrand ou le cynisme, from the Mémoires (1880) of Claire de Rémusat, lady-in-waiting to Empress Marie-Louise.

- ↑ Brooks, Xan (1 January 2009). "Happy birthday Salinger". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ Atlas, James (14 December 1994). "An Erudite Author in a Genre All His Own". The New York Times.

Further reading

Biographies

- Bernard, J.F. (1973). Talleyrand: A Biography. New York: Putnam. ISBN 0-399-11022-4.; major scholarly biography

- Brinton, Crane. Lives of Talleyrand (1936), 300pp scholarly study

- Cooper, Duff (1932). Talleyrand. New York: Harper. ISBN 0802137679.

- Ferraro, Guglielmo. The Reconstruction of Europe: Talleyrand and the Congress of Vienna, 1814–1815 (1941)

- Lawday, David (2006). Napoleon's Master: A Life of Prince Talleyrand. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-07366-0.

- Orieux, Jean. Talleyrand: The Art of Survival (1974) 677pp; scholarly biography

- Pflaum, Rosalynd. Talleyrand and His World (2010), popular biography

- Sked, Alan. "Talleyrand and England, 1792–1838: A Reinterpretation," Diplomacy & Statecraft (2006) 17#4 pp 647–664.

Scholarly studies

- Esdaile, Charles. Napoleon's Wars: An International History, 1803–1815 (2008); 645pp, a standard scholarly history

- Godechot, Jacques; Béatrice Fry Hyslop; David Lloyd Dowd; et al. (1971). The Napoleonic Era in Europe. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Ross, Steven T. European Diplomatic History, 1789–1815: France Against Europe (1969)

- Schroeder, Paul W. The Transformation of European Politics 1763–1848 (1994) 920pp; online; advanced analysis

Historiography

- Moncure, James A. ed. Research Guide to European Historical Biography: 1450–Present (4 vol 1992); 4:1823–33

Non-English language

- Potocka-Wąsowiczowa, Anna z Tyszkiewiczów (1965). Wspomnienia naocznego świadka. Warsaw, PL: PWN.

- Waresquiel, Emmanuel de (2003). Talleyrand: le prince immobile. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-61326-5.

- Tarle, Yevgeny (1939). Talleyrand. Moskow.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand. |

| Look up Talleyrandian in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article about Talleyrand. |

- Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Perigord 1754–1838

- Career of Mme Grand, Talleyrand's wife

- Bishop Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Perigord, Catholic Hierarchy website

- Talleyrands letters and dispatches translated into English

- Painting of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord by Baron Gérard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Works by prince de Bénévent Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord at Internet Archive

._D%C3%A9claration_des_Droits_et_des_Devoirs_de_l'Homme_et_du_Citoyen.jpg)