Chittor Fort

| Chittor Fort | |

|---|---|

| Part of Chittorgarh | |

| Rajasthan, India | |

|

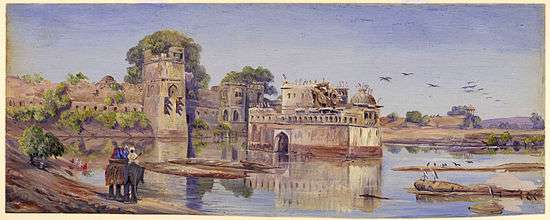

A view of Chittorgarh Fort | |

Chittor Fort | |

| Coordinates | 24°53′11″N 74°38′49″E / 24.8863°N 74.647°E |

| Site history | |

| Battles/wars | Mewar Kings against Allauddin Khilji in 1303 AD, Bahadur Shah, Sultan of Gujarat in 1535 AD and Emperor Akbar in 1568 AD |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Maurya dynasty, Bappa Rawal, Hammir Singh, Rana Sanga, Rana Kumbha and Udai Singh II |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii |

| Designated | 2013 (36th session) |

| Part of | Hill Forts of Rajasthan |

| Reference no. | 247 |

| State Party | India |

| Region | South Asia |

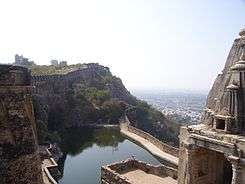

The Chittor Fort or Chittorgarh is one of the largest forts in India. It is a World Heritage Site. The fort was the capital of Mewar and is today situated in the Chittorgarh town. It sprawls over a hill 180 m (590.6 ft) in height spread over an area of 280 ha (691.9 acres) above the plains of the valley drained by the Berach River. The fort precinct has several historical palaces, gates, temples and two prominent commemoration towers. These monumental ruins have inspired the imagination of tourists and writers for centuries.[1][2][3]

From 7th century, the fort was ruled by the Mewar Kingdom. It was attacked three times by Muslim rulers: In 1303 Allauddin Khilji defeated Rana Ratan Singh, in 1535 Bahadur Shah, the Sultan of Gujarat defeated Bikramjeet Singh and in 1567 Akbar defeated Maharana Udai Singh II who left the fort and founded Udaipur. Each time the men fought bravely rushing out of the fort walls charging the enemy but lost every time. Following these defeats, Jauhar was committed thrice by more than 13,000 ladies and children of the Rajput soldiers who laid their lives in battles at Chittorgarh Fort, first led by Rani Padmini wife of Rana Rattan Singh who was killed in the battle in 1303, and later by Rani Karnavati in 1537 AD.[1][2][4] Thus, the fort represents the quintessence of tribute to the nationalism, courage, medieval chivalry and sacrifice exhibited by the Mewar rulers of Sisodia and their kinsmen and women and children, between the 7th and 16th centuries. The rulers, their soldiers, the women folk of royalty and the commoners considered death as a better option than dishonor in the face of surrender to the foreign invading armies.[1][4]

In 2013, at the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Chittorgarh Fort, along with 5 other forts of Rajasthan, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the group Hill Forts of Rajasthan.

Geography

Chittorgarh, located in the southern part of the state of Rajasthan, 233 km (144.8 mi) from Ajmer, midway between Delhi and Mumbai on the National Highway 8 (India) in the road network of Golden Quadrilateral. Chittorgarh is situated where National Highways No. 76 & 79 intersect.

The fort rises abruptly above the surrounding plains and is spread over an area of 2.8 km2 (1.1 sq mi). The fort stands on a hill 180 m (590.6 ft) high.[5] It is situated on the left bank of the Berach river (a tributary of the Banas River) and is linked to the new town of Chittorgarh (known as the 'Lower Town') developed in the plains after 1568 AD when the fort was deserted in light of introduction of artillery in the 16th century, and therefore the capital was shifted to more secure Udaipur, located on the eastern flank of Aravalli hill range. Mughal Emperor Akbar attacked and sacked this fort which was but one of the 84 forts of Mewar, but the capital was shifted to Aravalli hills where heavy artillery & cavalry were not effective. A winding hill road of more than 1 km (0.6 mi) length from the new town leads to the west end main gate, called Ram Pol, of the fort. Within the fort, a circular road provides access to all the gates and monuments located within the fort walls.[1][2][6][7]

The fort that once boasted of 84 water bodies has only 22 of them now. These water bodies are fed by natural catchment and rainfall, and have a combined storage of 4 billion litres that could meet the water needs of an army of 50,000. The supply could last for four years. These water bodies are in the form of ponds, wells and step wells.[8]

History

Chittorgarh (garh means fort) was originally called Chitrakut.[9] It is said to have been built by the local Maurya rulers (not to be confused with the imperial Mauryans).[10] According to one legend, the name of the fort is derived from its builder Chitranga.[9] Another folk legend attributes the construction of fort to the legendary hero Bhima: it states that Bhima struck the ground here, which resulted in water springing up to form a large reservoir. The water body allegedly formed by Bhima is an artificial tank called Bhimlat kund.[1][6] Several small Buddhist stupas dated to 9th century based on the script were found at the edge of Jaimal Patta lake.[11]

The Guhila (Gahlot) ruler Bappa Rawal is said to have captured the fort in either 728 CE or 734 CE. One account states that he received the fort in dowry.[9] According to other versions of the legend, Bappa Rawal captured the fort either from the mlechchhas or the Moris.[12] Historian R. C. Majumdar theorizes that the Moris (Mauryas) were ruling at Chittor when the Arabs (mlechchhas) invaded north-western India around 725 CE.[12] The Arabs defeated the Moris, and in turn, were defeated by a confederacy that included Bappa Rawal. R. V. Somani theorized that Bappa Rawal was a part of the army of Nagabhata I.[13] Some historians doubt the historicity of this legend, arguing that the Guhilas did not control Chittor before the reign of the later ruler Allata.[14]

Siege of 1303

Ala ud din Khilji, Sultan of Delhi, rallied his forces against Mewar, in 1303 AD. The Chittorgarh fort was till then considered impregnable and grand, atop a natural hill. But his immediate reason for invading the fort was his obsessive desire to capture Rani Padmini, the unrivalled beautiful queen of Rana Ratan Singh and take her into his harem. The Rana, out of politeness, allowed the Khilji to view Padmini through a set of mirrors. But this viewing of Padmini further fired Khilji's desire to possess her. After the viewing, as a gesture of courtesy, when the Rana accompanied the Sultan to the outer gate, he was treacherously captured. Khilji conveyed to the queen that the Rana would be released only if she agreed to join his harem. But the queen had other plans. She agreed to go to his camp if permitted to go in a Royal style with an entourage, in strict secrecy. Instead of her going, she sent 700 well armed soldiers disguised in litters and they rescued the Rana and took him to the fort. But Khilji chased them to the fort where a fierce battle ensued at the outer gate of the fort in which the Rajput soldiers were overpowered and the Rana was killed.

Khilji won the battle on August 26, 1303. Soon thereafter, instead of surrendering to the Sultan, the royal Rajput ladies led by Rani Padmini preferred to die through the Rajput's ultimate tragic rite of Jauhar (self immolation on a pyre). In revenge, Khilji killed thirty thousand Rajputs. He entrusted the fort to his son Khizr Khan to rule and renamed the fort as 'Khizrabad'.[15] He also showered gifts on his son by way of

a red canopy, a robe embroidered with gold and two standards one green and the other black and threw upon him rubies and emeralds.

He returned to Delhi after the fierce battle at the fort.[16]

Rana Hammir and successors

Khizr Khan's rule at the fort lasted till 1311 AD and due to the pressure of Rajputs he was forced to entrust power to the Sonigra chief Maldeva who held the fort for 7 years. Hammir Singh, usurped control of the fort from Maldeva by "treachery and intrigue" and Chittor once again regained its past glory. Hammir, before his death in 1364 AD, had converted Mewar into a fairly large and prosperous kingdom. The dynasty (and clan) fathered by him came to be known by the name Sisodia after the village where he was born. His son Ketra Singh succeeded him and ruled with honour and power. Ketra Singh's son Lakha who ascended the throne in 1382 AD also won several wars. His famous grandson Rana Kumbha came to the throne in 1433 AD and by that time the Muslim rulers of Malwa and Gujarat had acquired considerable clout and were keen to usurp the powerful Mewar state.[17]

Rana Kumbha and clan

There was resurgence during the reign of Rana Kumbha in the 15th century. Rana Kumbha, also known as Maharana Kumbhakarna, son of Rana Mokal, ruled Mewar between 1433 AD and 1468 AD. He is credited with building up the Mewar kingdom assiduously as a force to reckon with. He built 32 forts (84 fortresses formed the defense of Mewar) including one in his own name, called Kumbalgarh. But his death come in 1468 AD at the hands of his own son Rana Udaysimha (Uday Singh I) who assassinated him to gain the throne of Mewar. This patricide was not appreciated by the people of Mewar and consequently his brother Rana Raimal assumed the reins of power in 1473. After his death in May 1509, Sangram Singh (also known as Rana Sanga), his youngest son, became the ruler of Mewar, which brought in a new phase in the history of Mewar. Rana Sanga, with support from Medini Rai[18] (a Rajput chief of Alwar), fought a valiant battle against Mughal emperor Babar at Khanwa in 1527. He ushered in a period of prestige to Chittor by defeating the rulers of Gujarat and also effectively interfered in the matters of Idar. He also won small areas of the Delhi territory. In the ensuing battle with Ibrahim Lodi, Rana won and acquired some districts of Malwa. He also defeated the combined might of Sultan Muzaffar of Gujarat and the Sultan of Malwa. By 1525 AD, Rana Sanga had developed Chittor and Mewar, by virtue of great intellect, valour and his sword, into a formidable military state.[6][17] But in a decisive battle that was fought against Babar on March 16, 1527, the Rajput army of Rana Sanga suffered a terrible defeat and Sanga escaped to one of his fortresses. But soon thereafter in another attack on the Chanderi fort the valiant Rana Sanga died and with his death the Rajput confederacy collapsed.[17]

Siege of 1535

Bahadur Shah who came to the throne in 1526 AD as the Sultan of Gujarat besieged the Chittorgarh fort in 1535. The fort was sacked and, once again the medieval dictates of chivalry determined the outcome. Following the escape of the Rana, his brother Udai Singh and the faithful maid Panna Dhai to Bundi, it is said 13,000 Rajput women committed jauhar (self immolation on the funeral pyre) and 3,200 Rajput warriors rushed out of the fort to fight and die.[1][17]

Siege of 1567

.jpg)

The final Siege of Chittorgarh came 33 years later, in 1567, when the Mughal Emperor Akbar invaded the fort. Akbar wanted to conquer Mewar, which was being ably ruled by Rana Uday Singh II, a fine prince of Mewar. To establish himself as the supreme lord of Northern India, he wanted to capture the renowned fortress of Chittor, as a precursor to conquering the whole of India. Shakti Singh, son of the Rana who had quarreled with his father, had run away and approached Akbar when the later had camped at Dholpur preparing to attack Malwa. During one of these meetings, in August 1567, Shakti Singh came to know from a remark made in jest by emperor Akbar that he was intending to wage war against Chittor. Akbar had told Shakti Singh in jest that since his father had not submitted himself before him like other princes and chieftains of the region he would attack him. Startled by this revelation, Shakti Singh quietly rushed back to Chittor and informed his father of the impending invasion by Akbar. Akbar was furious with the departure of Shakti Singh and decided to attack Mewar to humble the arrogance of the Ranas. In September 1567, the emperor left for Chittor, and on October 20, 1567, camped in the vast plains outside the fort. In the meantime, Rana Udai Singh, on the advice of his council of advisors, decided to go away from Chittor to the hills of Udaipur. Rao Jaimal and Patta (Rajasthan), two army chieftains of Mewar, were left behind to defend the fort along with 8,000 Rajput warriors under their command. Akbar laid siege to the fortress. The battle continued till February 23, 1568. On that day Jaymal was seriously wounded but he continued to fight with support from Patta. Jayamal ordered jauhar to be performed when many beautiful princesses of Mewar and noble matrons committed self-immolation at the funeral pyre. Next day the gates of the fort were opened and Rajput soldiers rushed out to fight the enemies. Rao Jaimal and Rawat Patta Singh Sisodia who were at last killed in action. One figure estimates that only 5,000 Mughal soldiers were killed in action.

Precincts

| Chittorgarh Fort Precincts

|

|---|

The fort which is roughly in the shape of a fish has a circumference of 13 km (8.1 mi) with a maximum length of 5 km (3.1 mi) and it covers an area of 700 acres.[19] The fort is approached through a zig zag and difficult ascent of more than 1 km (0.6 mi) from the plains, after crossing over a bridge made in limestone. The bridge spans the Gambhiri River and is supported by ten arches (one has a curved shape while the balance have pointed arches). Apart from the two tall towers, which dominate the majestic fortifications, the sprawling fort has a plethora of palaces and temples (many of them in ruins) within its precincts.[3][6]

The 305 hectares component site, with a buffer zone of 427 hectares, encompasses the fortified stronghold of Chittorgarh, a spacious fort located on an isolated rocky plateau of approximately 2 km length and 155m width.

It is surrounded by a perimeter wall 13 km (8.1 mi) long, beyond which a 45° hill slope makes it almost inaccessible to enemies. The ascent to the fort passes through seven gateways built by the Mewar ruler Rana Kumbha (1433- 1468) of the Sisodia clan. These gates are called, from the base to the hill top, the Paidal Pol, Bhairon Pol, Hanuman Pol, Ganesh Pol, Jorla Pol, Laxman Pol, and Ram Pol, the final and main gate.

The fort complex comprises 65 historic built structures, among them 4 palace complexes, 19 main temples, 4 memorials and 20 functional water bodies. These can be divided into two major construction phases. The first hill fort with one main entrance was established in the 5th century and successively fortified until the 12th century. Its remains are mostly visible on the western edges of the plateau. The second, more significant defence structure was constructed in the 15th century during the reign of the Sisodia Rajputs, when the royal entrance was relocated and fortified with seven gates, and the medieval fortification wall was built on an earlier wall construction from the 13th century.

Besides the palace complex, located on the highest and most secure terrain in the west of the fort, many of the other significant structures, such as the Kumbha Shyam Temple, the Mira Bai Temple, the Adi Varah Temple, the Shringar Chauri Temple, and the Vijay Stambh memorial were constructed in this second phase. Compared to the later additions of Sisodian rulers during the 19th and 20th centuries, the predominant construction phase illustrates a comparatively pure Rajput style combined with minimal eclecticism, such as the vaulted substructures which were borrowed from Sultanate architecture. The 4.5 km walls with integrated circular enforcements are constructed from dressed stone masonry in lime mortar and rise 500m above the plain. With the help of the seven massive stone gates, partly flanked by hexagonal or octagonal towers, the access to the fort is restricted to a narrow pathway which climbs up the steep hill through successive, ever narrower defence passages. The seventh and final gate leads directly into the palace area, which integrates a variety of residential and official structures. Rana Kumbha Mahal, the palace of Rana Kumbha, is a large Rajput domestic structure and now incorporates the Kanwar Pade Ka Mahal (the palace of the heir) and the later palace of the poet Mira Bai (1498-1546). The palace area was further expanded in later centuries, when additional structures, such as the Ratan Singh Palace (1528–31) or the Fateh Prakash, also named Badal Mahal (1885-1930), were added.

Although the majority of temple structures represent the Hindu faith, most prominently the Kalikamata Temple (8th century), the Kshemankari Temple (825-850) the Kumbha Shyam Temple (1448) or the Adbuthnath Temple (15th- 16th century), the hill fort also contains Jain temples, such as Sattaees Devari, Shringar Chauri (1448) and Sat Bis Devri (mid-15th century) Also the two tower memorials, Kirti Stambh (12th century) and Vijay Stambha (1433-1468), are Jain monuments. They stand out with their respective heights of 24m and 37m, which ensure their visibility from most locations of the fort complex. Finally, the fort compound is home to a contemporary municipal ward of approximately 3,000 inhabitants, which is located near Ratan Singh Tank at the northern end of the property.

Gates

The fort has total seven gates (in local language, gate is called Pol), namely the Padan Pol, Bhairon Pol, Hanuman Pol, Ganesh Pol, Jodla Pol, Laxman Pol and the main gate named the Ram Pol (Lord Rama's Gate). All the gateways to the fort have been built as massive stone structures with secure fortifications for military defense. The doors of the gates with pointed arches are reinforced to fend off elephants and cannon shots. The top of the gates have notched parapets for archers to shoot at the enemy army. A circular road within the fort links all the gates and provides access to the numerous monuments (ruined palaces and 130 temples) in the fort.

During the second siege, Prince Bagh Singh died at the Padan Pol in 1535 AD. Rao Jaimal of Badnore and his clansman Kalla were killed by Akbar at a location between the Bhairon Pol and Hanuman Pol in the last siege of the fort in 1567 (Kalla carried the wounded Jaimal out to fight). Chhatris, with the roof supported by corbeled arches, have been built to commemorate the spots of their sacrifice. Their statues have also been erected, at the orders of Emperor Akbar, to commemorate their valiant deaths. At each gate, cenotaphs of Rao Jaimal (in the form of a statue of a Rajput warrior on horseback) and Patta have also been constructed. At Ram Pol, the entrance gate to the fort, a Chaatri was built in memory of the 15-year-old Patta of Kelwa, who had lost his father in battle, and saw the sword yielding mother and wife on the battle field who fought valiantly and died at this gate. He led the saffron robed Rajput warriors, who all died fighting for Mewar's honour. Suraj Pol (Sun Gate) provides entry to the eastern wall of the fort. On the right of Suraj Pol is the Darikhana or Sabha (council chamber) behind which lie a Ganesha temple and the zenana (living quarters for women). A massive water reservoir is located towards the left of Suraj Pol. There is also a peculiar gate, called the Jorla Pol(Joined Gate), which consists of two gates joined together. The upper arch of Jorla Pol is connected to the base of Lakshman Pol. It is said that this feature has not been noticed anywhere else in India. The Lokota Bari is the gate at the fort's northern tip, while a small opening that was used to hurl criminals into the abyss is seen at the southern end.[1][2][6][20]

Vijay Stambha

The Vijay Stambha (Tower of Victory) or Jaya Stambha, called the symbol of Chittor and a particularly bold expression of triumph, was erected by Rana Kumbha between 1458 and 1468 to commemorate his victory over Mahmud Shah I Khalji, the Sultan of Malwa, in 1440 AD. Built over a period of ten years, it raises 37.2 metres (122 ft) over a 47 square feet (4.4 m2) base in nine stories accessed through a narrow circular staircase of 157 steps (the interior is also carved) up to the 8th floor, from where there is good view of the plains and the new town of Chittor. The dome, which was a later addition, was damaged by lightning and repaired during the 19th century. The Stamba is now illuminated during the evenings and gives a beautiful view of Chittor from the top.[1][3][6][21]

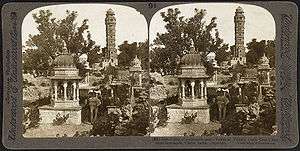

Kirti Stambha

Kirti Stambha (Tower of Fame) is a 22-metre-high (72 ft) tower built on a 30-foot (9.1 m) base with 15 feet (4.6 m) at the top; it is adorned with Jain sculptures on the outside and is older (probably 12th century) and smaller than the Victory Tower. Built by a Bagherwal Jain merchant Jijaji Rathod, it is dedicated to Adinath, the first Jain tirthankar (revered Jain teacher). In the lowest floor of the tower, figures of the various tirthankars of the Jain pantheon are seen in special niches formed to house them. These are digambara monuments. A narrow stairway with 54 steps leads through the six storeys to the top. The top pavilion that was added in the 15th century has 12 columns.[1][2][3][6][22][23]

Rana Kumbha Palace

At the entrance gate near the Vijaya Stamba, Rana Kumbha's palace (in ruins), the oldest monument, is located. The palace included elephant and horse stables and a temple to Lord Shiva. Maharana Udai Singh, the founder of Udaipur, was born here; the popular folk lore linked to his birth is that his maid Panna DaiPanna Dhai saved him by substituting her son in his place as a decoy, which resulted in her son getting killed by Banbir. The prince was spirited away in a fruit basket. The palace is built with plastered stone. The remarkable feature of the palace is its splendid series of canopied balconies. Entry to the palace is through Suraj Pol that leads into a courtyard. Rani Meera, the famous poet saint, also lived in this palace. This is also the palace where Rani Padmini, consigned herself to the funeral pyre in one of the underground cellars, as an act of jauhar along with many other women. The Nau Lakha Bandar (literal meaning: nine lakh treasury) building, the royal treasury of Chittor was also located close by. Now, across from the palace is a museum and archeological office. The Singa Chowri temple is also nearby.[1][2][6]

Fateh Prakash Palace

Located near Rana Khumba palace, built by Rana Fateh Singh, the precincts have modern houses and a small museum. A school for local children (about 5,000 villagers live within the fort) is also nearby.[1][6]

Gaumukh Reservoir

A spring feeds the tank from a carved cow's mouth in the cliff. This pool was the main source of water at the fort during the numerous sieges.[6]

Padmini's Palace

Padmini's Palace or Rani Padmini's Palace is a white building and a three storied structure (a 19th-century reconstruction of the original). It is located in the southern part of the fort. Chhatris (pavilions) crown the palace roofs and a water moat surrounds the palace. This style of palace became the forerunner of other palaces built in the state with the concept of Jal Mahal (palace surrounded by water). It is at this Palace where Alauddin was permitted to glimpse the mirror image of Rani Padmini, wife of Maharana Rattan Singh. It is widely believed that this glimpse of Padmini's beauty besotted him and convinced him to destroy Chittor in order to possess her. Maharana Rattan Singh was killed and Rani Padmini committed Jauhar. Rani Padmini's beauty has been compared to that of Cleopatra and her life story is an eternal legend in the history of Chittor. The bronze gates to this pavilion were removed and transported to Agra by Akbar.[1][2]

The story of Padmini was the inspiration for Padmavat, an epic poem written in 1540 by Malik Muhammad Jayasi.

Other Sights

Close to Kirti Sthamba is the Meera Temple, or the Meerabai Temple. Rana Khumba built it in an ornate Indo–Aryan architectural style. It is associated with the mystic saint-poet Mirabai who was an ardent devotee of Lord Krishna and dedicated her entire life to His worship. She composed and sang lyrical bhajans called Meera Bhajans. The popular legend associated with her is that with blessings of Krishna, she survived after consuming poison sent to her by her evil brother-in-law. The larger temple in the same compound is the Kumbha Shyam Temple (Varaha Temple).[1][2][6] The pinnacle of the temple is in pyramid shape. A picture of Meerabai praying before Krishna has now been installed in the temple.[24]

Across from Padmini's Palace is the Kalika Mata Temple. Originally, a Sun Temple dated to the 8th century dedicated to Surya (the Sun God) was destroyed in the 14th century. It was rebuilt as a Kali temple.[1][2][6]

Another temple on the west side of the fort is the ancient Goddess Tulja Bhavani Temple built to worship Goddess Tulja Bhavani is considered sacred. The Tope Khana (cannon foundry) is located next to this temple in a courtyard, where a few old cannons are still seen.[6]

Culture

The fort and the city of Chittorgarh host the biggest Rajput festival called the "Jauhar Mela".[5] It takes place annually on the anniversary of one of the jauhars, but no specific name has been given to it. It is generally believed that it commemorates Padmini's jauhar, which is most famous. This festival is held primarily to commemorate the bravery of Rajput ancestors and all three jauhars which happened at Chittorgarh Fort. A huge number of Rajputs, which include the descendants of most of the princely families, hold a procession to celebrate the Jauhar. It has also become a forum to air one's views on the current political situation in the country.[25]

Six forts of Rajasthan, namely, Amber Fort, Chittorgarh Fort, Gagron Fort, Jaisalmer Fort, Kumbhalgarh and Ranthambore Fort were included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site list during the 37th meeting of the World Heritage Committee in Phnom Penh during June 2013. They were recognized as a serial cultural property and examples of Rajput military hill architecture.[26][27]

Gallery

Columns in the fortress.

Columns in the fortress. A part of the fortress.

A part of the fortress. An old photo of the Kirti Stambha

An old photo of the Kirti Stambha An old photo of the Vijay Stambha

An old photo of the Vijay Stambha A recent photo of the Vijay Stambha (Tower of Victory)

A recent photo of the Vijay Stambha (Tower of Victory)- Fort remains 1

- Fort remains 2

- Structures in the fort 1

- Structures in the fort 2

Meera Temple

Meera Temple

Kirti Stambh, details

Kirti Stambh, details- Jain temple at Kirtistambha

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Joe Bindloss; James Bainbridge; Lindsay Brown; Mark Elliott; Stuart Butler (2007). India. Southern Rajasthan History. Lonely Planet. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Indian States and Union Territories". Places of Interest in Rajasthan: Chtiiorgarh. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chittorgarh Fort". Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- 1 2 Ministry of Information; Broadcasting, India (1985). Indian and foreign review. New Delhi : Government of India. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. Publications Division, 1963-1988. pp. 25–26. ISBN 0-00-019437-9. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- 1 2 "The Fantastic 5 Forts: Rajasthan Is Home to Some Beautiful Forts, Here Are Some Must-See Heritage Structures". DNA : Daily News & Analysis. 28 January 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2015 – via High Beam. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Chittorgarh Fort of Rajasthan in India". Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ "Places and Monuments". Archived from the original on 2009-07-17. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ↑ "Rajasthan's Water fort". Rainwaterharvesting.Org. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- 1 2 3 Paul E. Schellinger & Robert M. Salkin 1994, p. 191.

- ↑ Shiv Kumar Tiwari 2002, p. 271.

- ↑ Chittorgarh, Shobhalal Shastri, 1928, pp. 64-65

- 1 2 Majumdar 1977, p. 298-299.

- ↑ Somani 1976, p. 45.

- ↑ Somani 1976, p. 44.

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 83. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ↑ Ishwari Prasad. "A Short History of Muslim Rule in India". Khilji Imperialism. The Indian Press, Ltd. pp. paras 112 to 114. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- 1 2 3 4 Ishwari Prasad. "A Short History of Muslim Rule in India". India in the sixteenth century. The Indian Press, Ltd. pp. paras 281 to 287. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ Aain e Akbari by Shaikh Abul Fazl Nagori. Persian MS. India Office Library London, UK. English translation. The Asiatic Society Bombay, India. 2. Aasaar Us Sanadid by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan OBE. Urdu compilation of Delhi's history. Urdu Academy New Delhi, India. ISBN 81-7121-128-3

- ↑ "History of Chittorgarh Fort". Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ↑ Pippa De Bruyn; Keith Bain; Niloufer Venkatraman; Shonar Joshi (2006). Frommer's India. Chittauragarh (Chittor). Wiley Publishing, Inc. pp. 454=455. ISBN 0-7645-6777-2. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ "Tower of Victory, Chittore Fort". Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ "The Khowasin Stambha, a Jaina tower at Cheetore". Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ "Chittaurgarh Fort, Chittaurgarh". Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ↑ Laxman Prasad Mathur (1990). Forts and strongholds of Rajasthan. Mira Bai temple. New Delhi, India: Inter-India Publications. p. 24. ISBN 81-210-0229-X. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ B.S. Nijjar (2007). Origins and History of Jats and Other Allied Nomadic Tribes of India. Jauhar Mela at Chittor. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (P) Ltd. p. 306. ISBN 81-269-0908-0. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ↑ "Heritage Status for Forts". Eastern Eye. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2015 – via High Beam. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Iconic Hill Forts on UN Heritage List". New Delhi, India: Mail Today. 22 June 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2015 – via High Beam. (subscription required (help)).

Further reading

- Crump, Vivien; Toh, Irene (1996) [1996]. Rajasthan (hardback). New York: Everyman Guides. p. 400. ISBN 1-85715-887-3.

- Michell, George; Martinelli, Antonio (2005) [2005]. The Palaces of Rajasthan. London: Frances Lincoln. p. 271 pages. ISBN 978-0-7112-2505-3.

- Tillotson, G.H.R (1987) [1987]. The Rajput Palaces - The Development of an Architectural Style (Hardback) (First ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 224 pages. ISBN 0-300-03738-4.

- Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin, eds. (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. 5. Routledge/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781884964046.

- Somani, Ram Vallabh (1976). History of Mewar, from Earliest Times to 1751 A.D. Mateshwari. OCLC 2929852.

- Majumdar, R. C. (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120804364.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chittorgarh Fort. |