Culture of the Ottoman Empire

| Culture of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Visual arts |

| Performing arts |

| Languages and literature |

| Sports |

| Other |

Ottoman culture evolved over several centuries as the ruling administration of the Turks absorbed, adapted and modified the cultures of conquered lands and their peoples. There was a strong influence from the customs and languages of Islamic societies, Turkish "the official language for the Empire, notably Arabic because of the origins of Islam, while Persian culture had a significant contribution through the heavily Persianized Seljuq Turks, the Ottomans' predecessors. Despite newer added amalgamations, the Ottoman dynasty, like their predecessors in the Sultanate of Rum and the Seljuk Empire, were thoroughly Persianised in their culture, language, habits and customs, and therefore, the empire has been described as a Persianate empire."[1][2][3][4] Throughout its history, the Ottoman Empire had substantial subject populations of Byzantine Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Assyrians, who were allowed a certain amount of autonomy under the confessional millet system of Ottoman government, and whose distinctive cultures enriched that of the Ottoman state.

As the Ottoman Empire expanded it assimilated the culture of numerous regions under its rule and beyond, being particularly influenced by Byzantium, the Arab culture of the Islamic Middle East, and the Persian culture of Iran.

Literature

Poetry

As with many Ottoman Turkish art forms, the poetry produced for the Ottoman court circle had a strong influence from classical Persian traditions; a large number of Persian loanwords entered the literary language, and Persian metres and forms (such as those of Ghazal) were used.

By the 19th century and the era of Tanzimat reforms, the influence of Turkish folk literature, until then largely oral, began to appear in Turkish poetry, and there was increasing influence from the literature of Europe; there was a corresponding decline in classical court poetry. Tevfik Fikret, born in 1867, is often considered the founder of modern Turkish poetry.

Prose

Prior to the 19th century, Ottoman prose was exclusively non-fictional, and was much less highly developed than Ottoman poetry, in part because much of it followed the rules of the originally Arabic tradition of rhymed prose (Saj'). Nevertheless, a number of genres - the travelogue, the political treatise and biography - were current.

From the 19th century, the increasing influence of the European novel, and particularly that of the French novel, began to be felt. Şemsettin Sami's Taaşuk-u Tal'at ve Fitnat, widely considered the first Turkish novel, was published in 1872; other notable Ottoman writers of prose were Ahmet Mithat and Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil.

Architecture

Ottoman architecture was a synthesis of Iranian-influenced Seljuk architectural traditions, as seen in the buildings of Konya, Mamluk architecture, and Byzantine architecture; it reached its greatest development in the large public buildings, such as mosques and caravanserais, of the 16th century.

The most significant figure in the field, the 16th-century architect and engineer Mimar Sinan, was a Muslim convert of Armenian descent, having a background in the Janissaries. His most famous works were the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne and the Suleiman Mosque in Constantinople. One of his pupils, Sedefkar Mehmed Agha, designed the early 17th century Blue Mosque, considered the last great building of classical Ottoman architecture.

Decorative arts

Calligraphy

Calligraphy had a prestigious status under the Ottomans, its traditions having been shaped by the work of Abbasid calligrapher Yaqut al-Musta'simi of Baghdad, whose influence had spread across the Islamic world, al-Musta'simi himself possibly being of Anatolian origin.

The Diwani script is a cursive and distinctively Ottoman style of Arabic calligraphy developed in the 16th and early 17th centuries. It was invented by Housam Roumi, reaching its greatest development under Süleyman I the Magnificent (1520–66). The highly decorative script was distinguished by its complexity of line and by the close juxtaposition of the letters within words. Other forms included the flowing, rounded Nashki script, invented by the 10th-century Abbasid calligrapher Ali Muhammad ibn Muqlah, and Ta'liq, based on the Persian Nastalīq style.

Noted Ottoman calligraphers include Seyyid Kasim Gubari, Şeyh Hamdullah, Ahmed Karahisari, and Hâfiz Osman.

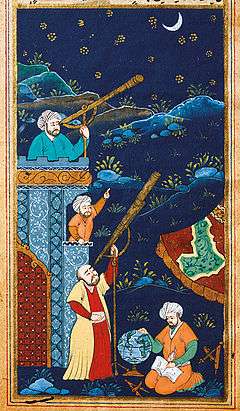

Miniatures

The Ottoman tradition of painting miniatures, to illustrate manuscripts or used in dedicated albums, was heavily influenced by the Persian art form, though it also included elements of the Byzantine tradition of illumination and painting. A Greek academy of painters, the Nakkashane-i-Rum was established in the Topkapi Palace in the 15th century, while early in the following century a similar Persian academy, the Nakkashane-i-Irani, was added.

Carpet-weaving and textile arts

The art of carpet weaving was particularly significant in the Ottoman Empire, carpets having an immense importance both as decorative furnishings, rich in religious and other symbolism, and as a practical consideration, as it was customary to remove one's shoes in living quarters.[5] The weaving of such carpets originated in the nomadic cultures of central Asia (carpets being an easily transportable form of furnishing), and was eventually spread to the settled societies of Anatolia. Turks used carpets, rugs and patterned kilims not just on the floors of a room, but also as a hanging on walls and doorways, where they provided additional insulation. They were also commonly donated to mosques, which often amassed large collections of them.[6]

Hereke carpets were of particularly high status, being made of silk or a combination of silk and cotton, and intricately knotted. Other significant designs included "Palace", "Yörük", Ushak, and Milas or "Türkmen" carpets. "Yörük" and "Türkmen" represented more stylized designs, whereas naturalistic designs were prevalent in "Palace".

Jewelry

The Ottoman Empire was noted for the quality of its gold- and silversmiths, and particularly for the jewelry they produced. Jewelry had particular importance as it was commonly given at weddings, as a gift that could be used as a form of savings.[7] Silver was the most common material used, with gold reserved for more high-status pieces; designs often displayed complex filigree work and incorporated Persian and Byzantine motifs. Developments in design reflected the tastes of the Ottoman court, with Persian Safavid art, for example, becoming an influence after the Ottoman defeat of Ismail I after the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514.[8] In the rural areas of the Empire, jewelry was simpler and often incorporated gold coins (the Ottoman altin), but the designs of Constantinople nevertheless spread throughout Ottoman territory and were reflected even in the metalwork of Egypt and North Africa.

Most jewelers and goldsmiths were Christian Armenians and Jews, but the interest of the Ottomans in the related art of watchmaking resulted in many European goldsmiths, watchmakers and gem engravers moving to Constantinople, where they worked in the foreigners' quarter, Galata.[9]

Performance

Music

Apart from the music traditions of its constituent peoples, the Ottoman Empire evolved a distinct style of court music, Ottoman classical music. This was a principally vocal form, with instrumental accompaniment, built on makamlar, a set of melodic systems, with a corresponding set of rhythmic patterns called usul.

Another distinctive feature of Ottoman music were the mehterân, the military bands used by the Janissaries and in the retinues of high-ranking officials. These bands were the ancestors of modern military bands, as well as of the brass ensembles popular in traditional Balkan music.

Dance

Dancing was an important element of Ottoman culture, which incorporated the folkloric dancing traditions of many different countries and lands on three continents; from the Balkan peninsula and the Black Sea regions to the Caucasus, the Middle East and North Africa.

Dancing was also one of the most popular pastimes in the Harem of Topkapı Palace.

The female belly dancers, named Çengi, were mostly from the Roma community. Today, living in Istanbul's Roma neighbourhoods like Sulukule, Kuştepe, Cennet and Kasımpaşa, they still dominate the traditional belly dancing and musical entertainment shows throughout the city's traditional taverns.

There were also male dancers, named Köçek, who took part in the entertainment shows and celebrations, accompanied by circus acrobats, named Cambaz, performing difficult tricks, and other shows which attracted curiosity.

Meddah (one person show)

The meddah or story teller played in front of a small group of viewers, such as a coffeehouse audience. The play was generally about a single topic, the meddah playing different characters, and was usually introduced by drawing attention to the moral contained in the story. The meddah would use props such as an umbrella, a handkerchief, or different headwear, to signal a change of character, and was skilled at manipulating his voice and imitating different dialects. There was no time limitation on the shows; a good meddah had the skill to adjust the story depending on interaction with the audience.

Meddahs were generally traveling artists whose route took them from one large city to another, such along the towns of the spice road; the tradition supposedly goes back to Homer's time. The methods of meddahs were the same as the methods of the itinerant storytellers who related Greek epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey, even though the main stories were now Ferhat ile Şirin or Layla and Majnun. The repertoires of the meddahs also included true stories, modified depending on the audience, artist and political situation.

The Istanbul meddahs were known to integrate musical instruments into their stories: this was a main difference between them and the East Anatolian Dengbejin.

In 2008 the art of the meddahs was relisted in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Karagöz (shadow play)

The Turkish shadow theatre, also known as Karagöz ("Black-Eyed") after one of its main characters, is descended from the Oriental Shadow theatre. Today, scholars generally consider the technique of a single puppeteer creating voices for a dialogue, narrating a story, and possibly even singing, all while manipulating puppets, to be an Indonesian invention.

Median (open stage show)

.png)

Sports

Turkish Wrestling is a very old tradition among the Turks.

- Yağlı güreş (Oil wrestling)

- Cirit (Equestrian javelin throw)

- Okçuluk (Turkish archery)

- Horoz Dövüşü (Cockfight)

Ottoman Turkish cuisine

The cuisine of Ottoman Turkey can be divided between that of the Ottoman court itself, which was a highly sophisticated and elaborate fusion of many of the culinary traditions found in the Empire, and the regional cuisines of the peasantry and of the Empire's minorities, which were influenced by the produce of their respective areas. Rice, for example, was a staple of high-status cookery (Imperial cooks were hired according to the skill they displayed in cooking it) but would have been regarded as a luxury item through most of Anatolia, where bread was the staple grain food.

Drinks

- Turkish Coffee - probably introduced from Levantine Arabic culture, coffee became central to Ottoman society - often accompanied with a Nargile (Narguile / Hookkah).

- Ayran - a traditional yogurt-based drink still popular throughout many areas of the former Empire.

- Sherbet - a spiced cold fruit drink.

- Rakı - a traditional Turkish drink which has alcohol in it.

Food

- Lokum (Turkish Delight)

- Şeker (Candies)

- Akide Şekeri

- Macun (Majoon)

- Pestil

- Sucuk

- Shish Kebab

- Çörek

- Baklava

- Lahmacun

- Döner

- Kebab

Science and technology

Timeline

- October 22, 1784 - Imperial Naval Engineering school

- Military Academy founded 1834

- Imperial School of Music founded 1836[10]

- April 1, 1847 - Institution of the Ministry of Education founded

- July 18, 1851 - Inauguration of the Academy of Sciences

- Civil Service School founded 1859

- Imperial Ottoman Lycée of Galatasaray founded 1868

Gallery

Boat tour at Göksu Creek

Boat tour at Göksu Creek Women and children dancing in the Harem of Topkapı Palace

Women and children dancing in the Harem of Topkapı Palace A lady from the Ottoman court playing the Def at the Harem

A lady from the Ottoman court playing the Def at the Harem

References

- ↑ Özgündenli, O. "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries". Encyclopaedia Iranica (online ed.).

- ↑ "Persian in service of the state: the role of Persophone historical writing in the development of an Ottoman imperial aesthetic", Studies on Persianate Societies, 2, 2004, pp. 145–63

- ↑ "Historiography. xi. Persian Historiography in the Ottoman Empire". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 12, fasc. 4. 2004. pp. 403–11.

- ↑ Walter, F. "7: The Departure of Turkey from the 'Persianate' Musical Sphere". Music of the Ottoman court.

- ↑ Foroqhi, S. Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire, I. B. Tauris, 2005, ISBN 1-85043-760-2, p. 152

- ↑ Foroqhi, p.153

- ↑ Foroqhi, p.108

- ↑ Newman, A. (ed) Society and Culture in the Early Modern Middle East, BRILL, 2003, ISBN 90-04-12774-7, p.177

- ↑ Göçek, F. East encounters West: France and the Ottoman Empire in the Eighteenth Century, OUP, 1987, ISBN 0-19-504826-1, p.106

- ↑ Gökçek, Mustafa (2001). "Centralization During the Era of Mahmud II". Journal of Ottoman Studies. XXI: 250.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culture of the Ottoman Empire. |

- Hatvesanat.com Source on Islamic Calligraphy Art (mainly (Turkish))

- Osmanlimedeniyeti.com Many articles about the Ottoman history and culture including art, culture, literature, economics, architecture (Turkish)

- KalemGuzeli.net Traditional arts in Ottoman Empire (mainly (Turkish))