Ottoman clothing

Ottoman clothing is the style and design of clothing worn by the Ottoman Turks.

Ottoman period

While the Palace and its court dressed lavishly, the common people were only concerned with covering themselves. Starting in the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, administrators enacted sumptuary laws upon clothing. The clothing of Muslims, Christians, Jewish communities, clergy, tradesmen, and state and military officials were particularly strictly regulated during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent.

In this period men wore outer items such as 'mintan' (a vest or short jacket), 'zıbın', 'şalvar' (trousers), 'kuşak' (a sash), 'potur', 'entari' (a long robe), 'kalpak', 'sarık' on the head; 'çarık', 'çizme', 'çedik', 'Yemeni' on the feet. The administrators and the wealthy wore caftans with fur lining and embroidery, whereas the middle class wore 'cübbe' (a mid-length robe) and 'hırka' (a short robe or tunic), and the poor wore collarless 'cepken' or 'yelek' (vest).

Women's everyday wear was şalvar (trousers), a gömlek (chemise) that came down to the mid-calf or ankle, a short, fitted jacket called a hırka, and a sash or belt tied at or just below the waist. For formal occasions, such as visiting friends, the woman added an entari, a long robe that was cut like the hırka apart from the length. Both hırka and entari were buttoned to the waist, leaving the skirts open in front. Both garments also had buttons all the way to the throat, but were often buttoned only to the underside of the bust, leaving the garments to gape open over the bust. All of these clothes could be brightly colored and patterned. However, when a woman left the house, she covered her clothes with a ferace, a dark, modestly cut robe that buttoned all the way to the throat. She also covered her face with a variety of veils or wraps.

Bashlyks, or hats, were the most prominent accessories of social status. While the people wore "külah's" covered with 'abani' or 'Yemeni', the cream of the society wore bashlyks such as 'yusufi, örfi, katibi, kavaze', etc. During the rule of Süleyman a bashlyk called 'perişani' was popular as the palace people valued bashlyks adorned with precious stones.

'Kavuk', however, was the most common type of bashlyk. For this reason, a related tradesmenship was formed in the 17th century. Fur was a material of prestige in that period. Political crises of the 17th century were reflected as chaos in clothes. The excessively luxurious compulsion of consumption and showing off in the Tulip Era lasted till the 19th century. The modernization attempts of Mahmut II in 1825 first had its effects in the state sector. While 'sarık' was replaced by 'fez', the people employed in Bab-ı Ali began to wear trousers, 'setre' and 'potin'.

During the 'Tanzimat' and 'Meşrutiyet' period in the 19th century, the common people still keeping to their traditional clothing styles presented a great contrast with the administrators and the wealthy wearing 'redingot', jacket, waistcoat, boyunbağı (tie), 'mintan', sharp-pointed and high-heeled shoes. Women's clothes of the Ottoman period were observed in the 'mansions' and Palace courts. 'Entari', 'kuşak', 'şalvar', 'başörtü', 'ferace' of the 19th century continued their existence without much change. In the 16th century women wore two-layer long 'entari' and 'tül', velvet shawl on their heads. Their outdoor clothing consisted of 'ferace' and 'yeldirme'. The simplification in the 17th century was apparent in an inner 'entari' worn under short-sleeved, caftan-shaped outfit and the matching accessory was a belt.

Women's wear becoming more showy and extravagant brought about adorned hair buns and tailoring. Tailoring in its real sense began in this period. The sense of women's wear primarily began in large residential centers such as Istanbul and İzmir in the 19th century and as women gradually began to participate in the social life, along with the westernization movement. Pera became the center of fashion and the Paris fashion was followed by the tailors of Greek and Armenian origin. In the period of Abdul Hamid II the use of 'ferace' (a concealing outer robe shaped like a modestly cut version of the indoor dress) was replaced by 'çarşaf' of different styles. However, the rural sector continued its traditional style of clothing.

Ottoman influence on Western Female Dress

Interactions between Ottomans and Britons occurred throughout history, but in the 18th century, European visitors and residents in the Ottoman Empire markedly increased, and exploded in the 19th century.[1] As such, fashion is one method to gauge the increased interactions. Historically, Europeans clothing was more delineated between male and female dress. Hose and trousers were reserved for men, and skirts were for women.[2] Conversely, in the Ottoman Empire, male and female dress was more similar. A common item worn by both was the şalvar, a voluminous undergarment in white fabric shaped like what are today called “harem pants".[3] To British women traveling in the Ottoman Empire, the şalvar quickly became a symbol of freedom because they observed that Ottoman women had more rights than British women did. Lady Mary Wortley Montague (1689-1762), whose husband was the British Ambassador to Istanbul, noted in her travels in her “Embassy Letters” that Ottoman women “possessed legal property rights and protections that far surpassed the rights of Western women”.[4] These female travelers often gained an intimate view of Ottoman culture, since as women, they had easier access to the Muslim Elite harems than did men.[5] Şalvar successfully spread into Europe at the end of the 19th century as various female suffragists and feminists used şalvar as a symbol of emancipation. Other British women of distinction, such as Lady (Janey) Archibal Campbell (1845-1923), and Lady Ottoline (Violet Anne) Morrell (1873-1938) wore şalvar “in an attempt to symbolize their refusal of traditional British standards and sexual differences”.[6] Şalvar also spread beyond Europe when Amelia Jenks Bloomer modified these “Turkish trousers” to create American “bloomers”.[7]

Another area where the Ottomans influenced female Western dress was in layering. Initially, layering had a practical use for the ancestors of the Ottoman Empire, who were pastoral nomads and horse riders, and needed to wear layers to adapt to changing temperatures.[8] But as the Ottoman Empire came into being, the layering of garments would distinguish one’s gender, class, or rank within particular communities, while also displaying many sumptuous fabrics, thus signaling one’s wealth and status. Layering also had spiritual significance. For instance, in Islamic art, layering different patterns represents a spiritual metaphor of the divine order that seems to be incomprehensible, but is actually planned and meaningful[9]

In Europe, in the 16th century, skirts began to have a layered appearance. Previous to the 16th century, skirts were slit only at the bottom, but now, the slit bisected the front of the skirt to reveal a contrasting layer underneath. Often, the under layer would coordinate with a layered sleeve.[10] Hanging sleeves were also a European concept that was derived from the Ottomans, although they arrived in Europe much earlier than layered skirts. In the 12th century, religious and scholarly peoples would wear coats that had hanging sleeves, similar to Turkish-style outer kaftans. These hanging sleeves meant one could see a second layer of fabric underneath the outer layer.[11] Although hanging sleeves had been present in Europe since the 12th century, they did not escape Lady Mary Montague’s fascination in the 18th century. In a letter dated March 10, 1717, she wrote to the Countess of Mar about Hafize (Hafsa) Sultan, a woman who was a favorite of the deposed Sultan Mustafa: “But her dress was something so surprisingly rich, that I cannot forbear describing it to you. She wore a vest called donalmá, which differs from a caftan by longer sleeves, and folding over the bottom. It was of purple cloth, straight to her shape, and thick set on each side, down to her feet, and round the sleeves, with pearls of the best water, of the same size as their buttons commonly are.” [12]

Republican period

The clothing styles prevailing until the mid 19th century imposed by religious reasons entered a transformation phase of the Republican period. In this period the 'şapka' and the following 'kılık kıyafet' reform realized with the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Kastamonu in 1925 had a full impact in Istanbul. Women's 'çarşaf' and 'peçe' were replaced by coat, scarf and shawl. Men began to wear hats, jackets, shirts, waistcoats, ties, trousers and shoes. With the industrialization process of the 1960s women entered the work life and tailors were substituted by readymade clothes industry. The contemporary fashion concept, as it is in the whole world, is apparent in both social and economic dimensions in Turkey as well.

Modern use

Modern Turkish designers such as Rıfat Özbek, Cemil İpekçi, Vural Gökçaylı, Yıldırım Mayruk, Sadık Kızılağaç, Hakan Elyaban, and Bahar Korçan draw inspiration from historical Ottoman designs, and Ottoman or Ottoman-inspired patterns are important to the Turkish textile industry.

Gallery

Religious garb

-rabbi.png) A Rabbi (1878)

A Rabbi (1878)-Armenian_patriarch.png) Armenian Orthodox Patriarch (1878)

Armenian Orthodox Patriarch (1878)-Greek_priest.png) Greek Orthodox Priest (1878)

Greek Orthodox Priest (1878)-ulema.png) Turkish Muslim alim (1878)

Turkish Muslim alim (1878)

Classical period

-Turkish_peasant.png) Turkish Peasant (1878)

Turkish Peasant (1878)-zeybek.png) Turkish Zeybek (1878)

Turkish Zeybek (1878)

Decline

-New_Picture_(51).png) Turkish Man (1878)

Turkish Man (1878)-Turkish_mrs._in_house.png) Turkish Woman at home (1878)

Turkish Woman at home (1878)-vield_turk_girl.png) Veiled Turkish Woman (1878)

Veiled Turkish Woman (1878)-bag_carrier.png) Porter (1878)

Porter (1878)-begging_dervis.png) Mendicant Dervish (1878)

Mendicant Dervish (1878)-dervis.png) Dervish (1878)

Dervish (1878)-boy.png) Turkish Boy (1878)

Turkish Boy (1878)-boy2.png) Turkish Boy (1878)

Turkish Boy (1878)-girl.png) Turkish Girl (1878)

Turkish Girl (1878)-girl12.png) Gypsy Girl (1878)

Gypsy Girl (1878)-sitting_on_edge.png) Men aboard a ferry (1878)

Men aboard a ferry (1878)-types_to_edge2.png) Men aboard a ferry (1878)

Men aboard a ferry (1878)-woman.png) Odalisque (1878)

Odalisque (1878)-woman2.png) Woman outdoors (1878)

Woman outdoors (1878)

Folk costumes in 1873

1. Burgher from Istanbul

1. Burgher from Istanbul

2. Aiwas (servant) 1. Caikdji (cabman)

1. Caikdji (cabman)

2. Sakka (water carrier)

3. Hammal (porter)

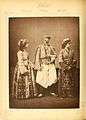

1. Turkish lady from Istanbul

1. Turkish lady from Istanbul

2. Turkish schoolboy 1. Armenian bride

1. Armenian bride

2. Jewish woman from Istanbul

3. Greek girl

1. Muslim horseman from Plovdiv

1. Muslim horseman from Plovdiv

2. Bulgarian woman from Koyountepe

3. Bulgarian woman from Ah'i Tchelebi

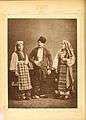

1: Bulgarian from Sofia

1: Bulgarian from Sofia

2. Bulgarian woman from Sofia

1: Hodja from Shkodër

1: Hodja from Shkodër

2. Christian priest from Shkodër 1: Muslim lady from Shkodër

1: Muslim lady from Shkodër

2. Christian lady from Shkodër

3. Peasant woman from Malissor 1: Muslim from Shkodër

1: Muslim from Shkodër

2. Muslim lady from Shkodër 1: Christian from Shkodër

1: Christian from Shkodër

2. Christian lady from Shkodër 1: Shepherd and peasant woman from Malissor

1: Shepherd and peasant woman from Malissor

1: Arnaut from Ioannina (middle class)

1: Arnaut from Ioannina (middle class)

2. Arnaut from Ioannina (lower class) 1: Wallachian (Aromanian) Woman from Ioannina

1: Wallachian (Aromanian) Woman from Ioannina

2. Christian woman from Preveza

3. Peasant woman from around Trikala

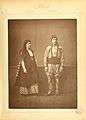

1. Muslim Artisan man and woman from Çanakkale

1. Muslim Artisan man and woman from Çanakkale

1. Yorouk woman from Biga

1. Yorouk woman from Biga

2. Christian woman from Chios

3. Christian woman from Lemnos 1. Muslim from Rhodes

1. Muslim from Rhodes

2. Muslim lady from Rhodes 1. Jew from Rhodes

1. Jew from Rhodes

2. Jewish woman from Rhodes

1. Peasant man and woman from around Bursa (wearing wedding clothing)

1. Peasant man and woman from around Bursa (wearing wedding clothing)

2. Seis (horse groom) 1. Jew and Jewish woman from Bursa

1. Jew and Jewish woman from Bursa

1. Muslim lady from Manisa

1. Muslim lady from Manisa

2. Muslim lady from Izmir

1. Armenian Priest from Konya

1. Armenian Priest from Konya

2. Mullah from Konya

3. Greek Priest from Konya

1. Bashi-bazouk from Ankara

1. Bashi-bazouk from Ankara

2. Muslim peasant from around Ankara

3. Muslim peasant woman from around Ankara 1. Kurdish woman from around Yuzgat

1. Kurdish woman from around Yuzgat

2. Female Christian artisan from Ankara

3. Muslim female artisan from Ankara

1. Muslim lady from Trabzon (indoor dress)

1. Muslim lady from Trabzon (indoor dress)

2. The same (outdoor dress)

1. Muslim lady from Diyarbakır.

1. Muslim lady from Diyarbakır.

2. Christian lady from Diyarbakır

3. A woman from Palu

1. Muslim lady from Sa'nt (indoor clothing)

1. Muslim lady from Sa'nt (indoor clothing)

2. The same (outdoor clothing)

3. Turkizh woman from Elâzığ

1. Christian inhabitant of Beirut (summer dress)

1. Christian inhabitant of Beirut (summer dress)

2. Muslim lady from Beirut

3. Christian lady from Beirut (winter dress) 1. Muslim from Lebanon

1. Muslim from Lebanon

2. Muslim woman from Lebanon

1. Christian woman from Zahlé (Lebanon)

1. Christian woman from Zahlé (Lebanon)

2. Christian woman from Zgharta (Lebanon)

3. Druze woman from Lebanon 1. Bedouin from Mount Lebanon.

1. Bedouin from Mount Lebanon.

2. Bedouin woman from Lebanon

1. Fellah woman from around Damascus

1. Fellah woman from around Damascus

2. Druze woman from around Damascus

3. Lady from Damascus 1. Christian artisan from Belka

1. Christian artisan from Belka

2. Artisan woman from Belka

3. Peasant Muslim woman from around Belka 1. Shopkeeper from Belka

1. Shopkeeper from Belka

2. Fellah from around Belka

3. Muslim artisan from Belka 1. Jew from Jerusalem

1. Jew from Jerusalem

2. Jewish woman from Jerusalem 1. Arab lady from Jerusalem

1. Arab lady from Jerusalem

2. Fellah from around Jerusalem

3. Fellah woman from around Jerusalem

- Vilayets of Baghdad; Hejaz; Yemen; Tripolitania

1. A'alim from Mecca

1. A'alim from Mecca

2. Inhabitant from Djeaddele (environs of Mecca)

3. Baveri of the guard of the Sharif of Mecca 1. Kabyle of the Harb tribe (environs of Medina)

1. Kabyle of the Harb tribe (environs of Medina)

2. Kabyle woman of the Harb tribe (environs of Medina)

3. Muslim woman from Djeaddele (environs of Mecca)

See also

References

- ↑ Charlotte Jirousek. Ottoman Costumes: From Textile to Identity. S Faroqhi and C. Neumann, ed. Istanbul: Eren Publishing, 2005. http://char.txa.cornell.edu/influences.htm

- ↑ Inal, Onur. "Women's Fashions in Transition: Ottoman Borderlands and the Anglo-Ottoman Exchange of Costumes." Journal of World History 22.2 (2011): 243-72. Web. p. 234

- ↑ Inal, p. 252

- ↑ Jirousek, p. 8

- ↑ Inal, p. 264

- ↑ Inal, p. 258

- ↑ Jirousek, p. 9

- ↑ Jirousek, p. 2

- ↑ Jirousek, p.2

- ↑ Jirousek, p. 12

- ↑ Jirousek, p. 12

- ↑ Inal, p.253

- Feyzi, Muharrem. Eski Türk Kıyafetleri ve Güzel Giyim Tarzları.

- Koçu, Reşat Ekrem. Türk Giyim Kuşam ve Süslenme Sözlüğü. Ankara: Sümerbank, 1967.

- Küçükerman, Önder. Türk Giyim Sanayinin Tarihi Kaynakları. İstanbul: GSD Dış Ticaret AŞ, 1966.

- Sevin, Nurettin. Onüç Asırlık Türk Kıyafet Tarihine Bir Bakış. Ankara: T.C. Kültür Bakanlığı, 1990.

- Tuğlacı, Pars. Osmanlı Saray Kadınları / The Ottoman Palace Women. Istanbul: Cem Yayınevi,1985.