Geology of Minnesota

.pdf.jpg)

The geology of Minnesota comprises the rock, minerals, and soils of the U.S. state of Minnesota, including their formation, development, distribution, and condition.

The state's geologic history can be divided into three periods. The first period was a lengthy period of geologic instability from the origin of the planet until roughly 1,100 million years ago. During this time, the state's Precambrian bedrock was formed by volcanism and the deposition of sedimentary rock and then modified by processes such as faulting, folding and erosion. In the second period, many layers of sedimentary rock were formed by deposition and lithification of successive layers of sediment from runoff and repeated incursions of the sea. In the third and most recent period starting about 1.8 million years ago, glaciation eroded previous rock formations and deposited deep layers of glacial till over most of the state, and created the beds and valleys of modern lakes and rivers.

Minnesota’s geologic resources have been the historical foundation of the state's economy. Precambrian bedrock has been mined for metallic minerals, including iron ore, on which the economy of Northeast Minnesota was built. Archaen granites and gneisses, and later limestones and sandstones, are quarried for structural stone and monuments. Glacial deposits are mined for aggregates, glacial till and lacustrine deposits formed the parent soil for the state's farmlands, and glacial lakes are the backbone of Minnesota's tourist industry. These economic assets have in turn dictated the state's history and settlement patterns, and the trade and supply routes along the waterways, valleys and plains have become the state's state's transportation corridors.

Geological history

Precambrian bedrock

Minnesota contains some of the oldest rocks on Earth, granitic gneisses that formed some 3,600 mya (million years ago) — roughly 80% the age of the planet.[1] About 2,700 mya, the first volcanic rocks that would later underlie Minnesota began to rise up out of an ancient ocean, forming the Superior craton.[2] This craton later assembled into the Canadian shield, which became part of the North American craton. Much of the underlying gneiss rock of today's state had already formed nearly a billion years earlier, but lay underneath the sea.[3] Except for an area where islands appeared in what is now the northern part of the state, most of the region remained underwater.

In Middle Precambrian time, about 2,000 mya, the land rose above the water. Heavy mineral deposits containing iron had collected on the shores of the receding sea to form the Mesabi, Cuyuna, Vermilion, and Gunflint iron ranges from the center of the state north into Northwestern Ontario, Canada.[4] These regions also showed the first signs of life as algae grew in the shallow waters.

Over 1,100 mya, a rift formed and lava emerged from cracks along the edges of the rift valley. This Midcontinent Rift System extended from the lower peninsula of Michigan north to the current Lake Superior, southwest through the lake to the Duluth area, and south through eastern Minnesota down into what is now Kansas.[5] The rifting stopped before the land could become two separate continents. About 100 million years later, the last volcano went quiet.

Late Precambrian and Paleozoic sedimentary rock

The mountain-building and rifting events left areas of high relief above the low basin of the Midcontinent rift. Over the next 1,100 million years, the uplands were worn down and the rift filled with sediments, forming rock ranging in thickness from several hundred meters near Lake Superior to thousands of meters further south.[6] While the crustal tectonic plates continued their slow drift over the surface of the planet, meeting and separating in the successive collision and rifting of continents, the North American craton remained stable.[7] Although now free of folding and faulting caused by plate tectonics, the region continued to experience gradual subsidence and uplift.[8]

Five hundred fifty million years ago, the state was repeatedly inundated with water of a shallow sea that grew and receded through several cycles. The land mass of what is now North America ran along the equator, and Minnesota had a tropical climate.[9] Small marine creatures such as trilobites, coral, and snails lived in the sea. The shells of the tiny animals sank to the bottom, and are preserved in limestones, sandstones, and shales from this era.[4] Later, creatures resembling crocodiles and sharks slid through the seas, and fossil shark teeth have been found on the uplands of the Mesabi Range.[10] During the Mesozoic and Cenozoic other land animals followed as the dinosaurs disappeared, but much of the physical evidence from this era has been scraped away or buried by recent glaciation. The rock units that remain in Minnesota from this time period are of Cambrian and Ordovician age, from the Mount Simon Sandstone at the bottom of the sequence of sedimentary rocks to the Maquoketa Group at the top.

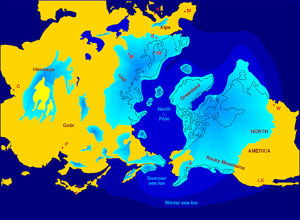

Ice ages

In the Quaternary Period starting about two million years ago, glaciers expanded and retreated across the region. The ice retreated for the last time about 12,500 years ago.[11] Melting glaciers formed many of the state's lakes and etched its river valleys. They also formed a number of proglacial lakes, which contributed to the state's topography and soils. Principal among these lakes was Lake Agassiz, a massive lake with a volume rivaling that of all the present Great Lakes combined. Dammed by the northern ice sheet, this lake's immense flow found an outlet in glacial River Warren, which drained south across the Traverse Gap through the valleys now occupied by the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. Eventually, the ice sheet melted, and the Red River gave Lake Agassiz a northern outlet toward Hudson Bay. As the lake drained away its bed became peatlands and a fertile plain. Similarly, Glacial Lake Duluth, in the basin of Lake Superior, was dammed by a glacier; it drained down the ancient course of the Midcontinental Rift to the St. Croix River and the Mississippi. When the glaciers receded, the lake was able to drain through the Great Lakes to the Saint Lawrence River.[12]

Giant animals roamed the area. Beavers were the size of bears, and mammoths were 14 feet (4.3 m) high at the shoulder and weighed 10 tons. Even buffalo were much larger than today. The glaciers continued to retreat and the climate became warmer over the next few millennia; the giant creatures died out about 9,000 years ago.[13]

This glaciation has drastically remodeled most of Minnesota, and all but two of the state's regions are covered with deep layers of glacial till.[14] The driftless area of Southeastern Minnesota was untouched by the most recent glaciation. In the absence of glacial scouring and drift, this region presents a widespread highly dissected aspect absent from other parts of the state. Northeastern Minnesota was subject to glaciation and its effects, but its hard Archaen and Proterozoic rocks were more resistant to glacial erosion than the sedimentary bedrock first encountered in many other regions, and glacial till is relatively sparse. While the effects of glacial erosion are clearly present and there are some areas of glacial till, older rocks and landforms remain unburied and exposed across much of the region.

Minnesota today

Contemporary Minnesota is much quieter geologically than in the past. Outcroppings of lava flows and magma intrusions are the only remaining traces of the volcanism that ended over 1,100 mya. Landlocked within the continent, the state is a long distance from the seas that once covered it, and the continental glacier has receded entirely from North America. Minnesota's landscape is a relatively flat peneplain; its highest and lowest points are separated by only 518 metres (1,699 ft) of elevation.[15]

While the state no longer has true mountain ranges or oceans, there is a fair amount of regional diversity in landforms and geological history, which in turn has affected Minnesota's settlement patterns, human history, and economic development. These diverse geological regions can be classified several ways. The classification used below principally derives from Sansome's Minnesota Underfoot - A Field Guide to Minnesota's Geology, but is also influenced by Minnesota's Geology by Ojakangas and Matsch. These authorities generally agree on areal borders, but the regions as defined by Ojakangas and Matsch are more geographical in their approximations of areas of similar geology, while Sansome's divisions are more irregular in shape in order to include within a region all areas of similar geology, with particular emphasis on the effects of recent glaciation. As glaciation and its residue has largely dictated regional surface geology and topography, Sansome's divisions are often coextensive with ecological provinces, sections, and subsections.[16]

Northeastern Minnesota: ancient bedrock

Northeastern Minnesota is an irregularly-shaped region composed of the northeasternmost part of the state north of Lake Superior, the area around Jay Cooke State Park and the Nemadji River basin southwest of Duluth, and much of the area east of U.S. Highway 53 that runs between Duluth and International Falls. Excluded are parts of the beds of glacial lakes Agassiz and Upham, the latter now occupied by the upper valley of the Saint Louis River and its tributary the Cloquet. This area is coextensive with the Northern Superior Uplands Section of the Laurentian Mixed Forest.[17]

Known as the Arrowhead for its shape, this region shows the most visible evidence of the state's violent past. There are surface exposures of rocks first formed in volcanic activity some 2,700 mya during construction of the Archaen-Superior province,[18] including Ely greenstone, metamorposed and highly folded volcanics once thought to be the oldest exposed rock on earth;[19] Proterozoic formations created about 1,900 mya that gave the area most of its mineral riches; and more recent intrusive gabbro and extrusive basalts and rhyolites of the Duluth Complex and North Shore Volcanic Group, created by magma and lava which upwelled and hardened about 1,100 mya during the Midcontinent Rift.[20] The Precambrian bedrock formed by this activity has been eroded but remains at or close to the surface over much of the area.

The entire area is the raw southern edge of the Canadian Shield. Topsoils are thin and poor and their parent soils derived from the rock beneath or nearby rather than from glacial till, which is sparse.[21] Many of this region's lakes are located in depressions formed by the differential erosion of tilted layers of bedded rock of the Canadian Shield; the crevasses thereby formed have filled with water to create many of the thousands of lakes and swamps of the Superior National Forest.[22]

In post-glacial times Northeastern Minnesota was covered by forest broken only by these interconnected lakes and wetlands. Much of the area has been little changed by human activity, as there are substantial forest and wilderness preserves, most notably the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and Voyageurs National Park. In the remainder of the region, lakes provide recreation, forests are managed for pulpwood, and the underlying bedrock is mined for valuable ores deposited in Precambrian times. While copper and nickel ores have been mined, the principal metallic mineral is iron. Three of Minnesota's four iron ranges are in the region, including the Mesabi Range, which has supplied over 90% of the state's historic output, including most of the natural ores pure enough to be fed directly into furnaces. The state's iron mines have produced over three and a half billion metric tons of ore.[23] While high-grade ores have now been exhausted, lower-grade taconite continues to supply a large proportion of the nation's needs.

Northwestern Minnesota: glacial lakebed

Northwestern Minnesota is a vast plain in the bed of Glacial Lake Agassiz. This plain extends north and northwest from the Big Stone Moraine, beyond Minnesota's borders into Canada and North Dakota. In the northeast, the Glacial Lake Agassiz plain transitions into the forests of the Arrowhead. The region includes the lowland portions of the Red River watershed and the western half of the Rainy River watershed within the state, at approximately the level of Lake Agassiz’ Herman Beach.[24] In ecological terms, it includes the Northern Minnesota Peatlands of the Laurentian Mixed Forest,[25] the Tallgrass Aspen Parklands,[26] and the Red River Valley Section of the Prairie Parklands.[27]

Bedrock in this region is mainly Archean, with small areas of Lower Paleozoic and Upper Mesozoic sedimentary rocks along the western border.[28] By late Wisconsinan times this bedrock had been covered by clayey glacial drift scoured and transported from sedimentary rocks of Manitoba. The bottomland is undissected and essentially flat, but imperceptibly declines from about 400 meters at the southern beaches of Lake Agassiz to 335 meters along the Rainy River. There is almost no relief, except for benches or beaches where Glacial Lake Agassiz stabilized for a time before it receded to a lower level. In contrast to the lakebed, these beaches rise from the south to the north and east at a gradient of approximately 1:5000; this rise resulted from the isostatic rebound of the land after recession of the last ice sheet.[29] In the western part of the region in the Red River Valley, fine-grained glacial lake deposits and decayed organic materials up to 50 meters in depth form rich, well-textured, and moisture-retentive, yet well-drained soils (mollisols), which are ideal for agriculture.[30] To the north and east, much of the land is poorly drained peat, often organized in rare and distinctive patterns known as patterned peatland.[31] [32] At marginally higher elevations within these wetlands are areas of black spruce, tamarack, and other water-tolerant species.

Southwestern Minnesota: glacial river and glacial till

Southwestern Minnesota is in the watersheds of the Minnesota River, the Missouri River, and the Des Moines River.[33] The Minnesota River lies in the bed of the glacial River Warren, a much larger torrent that drained Lake Agassiz while outlets to the north were blocked by glaciers. The Coteau des Prairies divides the Minnesota and Missouri River valleys, and is a striking landform created by the bifurcation of different lobes of glacial advance. On the Minnesota side of the coteau is a feature known as Buffalo Ridge, where wind speeds average 16 mph (26 km/h). This windy plateau is being developed for commercial wind power, contributing to the state's ranking as third in the nation for wind-generated electricity.[34]

Between the river and the plateau are flat prairies atop varying depths of glacial till. In the extreme southwest portion of the state, bedrock outcroppings of Sioux Quartzite are common, with less common interbedded outcrops of an associated metamorphosed mudstone named catlinite. Pipestone, Minnesota is the site of historic Native American quarries of catlinite, which is more commonly known as "pipestone". Another notable outcrop in the region is the Jeffers Petroglyphs, a Sioux Quartzite outcropping with numerous petroglyphs which may be up to 7000–9000 years old.[35]

Drier than most of the rest of the state, the region is a transition zone between the prairies and the Great Plains. Once rich in wetlands known as prairie potholes,[36] 90%, or some three million acres (12,000 km²), have been drained for agriculture in the Minnesota River basin.[37] Most of the prairies are now farm fields.[37] Due to the quaternary and bedrock geology of the region, as well as the reduced precipitation in the region, groundwater resources are neither plentiful, nor widely distributed, unlike most other areas of the state. Given these constraints, this rural area hosts a vast network of water pipelines which transports groundwater from the few localized areas with productive groundwater wells to much of the region's population.

Southeastern Minnesota: bluffs, caves and sinkholes

Southeastern Minnesota is separated from Southwestern Minnesota by the Owatonna Moraine, the eastern branch of the Bemis Moraine, a terminal moraine of the Des Moines lobe from the last Wisconsin glaciation.[12] Ojakangas and Matsch extend the region west past the moraine to a line running north from the Iowa border between Mankato and New Ulm to the latitude of the Twin Cities, then encompassing the latter metropolis with a broad arc east to the St. Croix River.[38] This moraine runs south from the Twin Cities in the general area of Minnesota State Highway 13 and Interstate 35. Sansome attaches this moraine to her description of West-Central Minnesota, given its similarity in glacial features to that region.[39] Under Sansome's classification (followed here), Southeastern Minnesota is generally coterminous with the Paleozoic Plateau Section of the Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province.[40]

The bedrock here is lower Paleozoic sedimentary rocks, with limestone and dolomite especially prevalent near the surface. It is highly dissected, and local tributaries of the Mississippi have cut deep valleys into the bedrock. It is an area of karst topography, with thin topsoils lying atop porous limestones, leading to formation of caverns and sinkholes. The last glaciation did not cover this region (halting at the Des Moines terminal lobe mentioned above), so there is no glacial drift to form subsoils, giving the region the name of the Driftless area. As the topsoils are shallower and poorer than those to the west, dairy farming rather than cash crops is the principal agricultural activity.

Central Minnesota: knob and kettle country

Central Minnesota is composed of (1) the drainage basin of the St. Croix River (2) the basin of the Mississippi River above its confluence with the Minnesota, (3) those parts of the Minnesota and Red River basins on the glacial uplands forming the divides of those two basins with that of the Mississippi, (4) the Owatonna Moraine atop a strip of land running from western Hennepin County south to the Iowa border, and (5) the upper valley of the Saint Louis River and the valley of its principal tributary the Cloquet River which once drained to the Mississippi before they were captured by stream piracy and their waters were redirected through the lower Saint Louis River to Lake Superior.[41][42] Glacial landforms are the common characteristics of this gerrymander-like region.

The bedrock ranges in age from Archean granites to Upper Mesozoic Cretaceous sediments,[43] and underlying the eastern part of the region (and the southerly extension to Iowa) are the Late Precambrian Keweenawan volcanics of the Midcontinent Rift, overlaid by thousands of meters of sedimentary rocks.[44]

At the surface, the entire region is "Moraine terrain", with the glacial landforms of moraines, drumlins, eskers, kames, outwash plains and till plains, all relics from recent glaciation. In the multitude of glacier-formed depressions are wetlands and many of the state's "10,000 lakes", which make the area prime vacation territory. The glacial deposits are a source of aggregate, and underneath the glacial till are high-quality granites which are quarried for buildings and monuments.

East Central Minnesota: bedrock valleys and outwash plain

The subregion of East Central Minnesota is that part of Central Minnesota near the junction of three of the state's great rivers. Included are Dakota County, eastern Hennepin County, and the region north of the Mississippi but south of an east-west line from Saint Cloud to the St. Croix River on the Wisconsin border. It includes much of the Twin Cities metropolitan area.[45] The region has the same types of glacial landforms as the remainder of Central Minnesota, but is distinguished by its bedrock valleys, both active and buried.

The valleys now hold three of Minnesota's largest rivers, which join here. The St. Croix joins the Mississippi at Hastings. Upstream, the Mississippi is joined by the Minnesota River at historic Fort Snelling. When River Warren Falls receded past the confluence of the much smaller Upper Mississippi River, a new waterfall was created where that river entered the much-lower River Warren. The new falls receded upstream on the Mississippi, migrating eight miles (13 km) over 9600 years to where Louis Hennepin first saw it and named St. Anthony Falls in 1680. Due to its value as a power source, this waterfall determined the location of Minneapolis. One tributary of the river coming from the west, Minnehaha Creek receded only a few hundred yards from one of the channels of the Mississippi. Minnehaha Falls remains as a picturesque and informative relic of River Warren Falls, and the limestone-over-sandstone construction is readily apparent in its small gorge. At St. Anthony Falls, the Mississippi dropped 50 feet (15 m) over a limestone ledge; these waterfalls were used to drive the flour mills that were the foundation for the city's 19th century growth.

Other bedrock tunnel valleys lie deep beneath till deposited by the glaciers which created them, but can be traced in many places by the Chain of Lakes in Minneapolis and lakes and dry valleys in St. Paul.

North of the metropolitan area is the Anoka Sandplain, a flat area of sandy outwash from the last ice age.[46] Along the eastern edge of the region are the Dalles of the St. Croix River, a deep gorge cut by runoff from Glacial Lake Duluth into ancient bedrock.[47] Interstate Park here contains the southernmost surface exposure of the Precambrian lava flows of the Midcontinent Rift, providing a glimpse of Minnesota's volcanic past.[48]

References

Notes

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota's Geology, p. 23.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota's Geology, pp. 25-32.

- ↑ "Minnesota". America’s Volcanic Past: Places. U.S.Geological Survey, Cascades Volcanic Observatory. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- 1 2 "Natural History - Minnesota's Geology". Minnesota Dept. of Natural Resources. 2007. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Van Schmus et al., The Midcontinent Rift System, pp. 345, 349.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, pp. 57-59.

- ↑ Townsend, Catherine L.; John T. Figge (2002). "Dance of the Giant Continents". Northwest Origins. Burke Museum of History and Culture, University of Washington. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, p. 65.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, pp. 65-95.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota's Geology, pp. 91-93.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, pp. 97, 108.

- 1 2 Lusardi, B.A. (1997). "Quaternary Glacial Geology" (PDF). Minnesota at a Glance. Minnesota Geological Survey, University of Minnesota. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, pp. 116-18.

- ↑ Jirsa and Southwick, Mineral Potential and Geology of Minnesota, Glacial cover in Minnesota.

- ↑ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S Geological Survey. 2005. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Ecological Classification System, Ecological Land Classification Hierarchy.

- ↑ Ecological Classification System, Northern Superior Uplands Section.

- ↑ Van Schmus et al., The Midcontinent Rift System, p. 348.

- ↑ Chandler, A Geophysical Investigation of the Ely Greenstone Belt in the Soudan Area Archived November 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., pp. 4-5; Nute, Rainy River Country, p. 3. Older rocks have since been found in Minnesota (the Morton gneiss of Southeast Minnesota) and Greenland and Labrador. Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota's Geology, p. 24.

- ↑ Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot: A Field Guide to Minnesota's Geology, pp. 19, 30, 36; Ojakagas and Matsch, Minnesota's Geology, pp. 37-40, 50-55, 191.

- ↑ Heinselman, The Boundary Waters Wilderness Ecosystem, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, pp. 185, 190-91.

- ↑ Morey, G. B. (February 1999). "High-grade iron ore deposits of the Mesabi Range, Minnesota; product of a continental-scale Proterozoic ground-water flow system". Economic Geology. 94 (1): 133–42. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.94.1.133.

- ↑ Compare regional map at Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot at p. 173, with image showing Herman Beach at Ojakanas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, at p. 201. The upland portions of the Red River watershed atop the moraine are different in character, with gravelly soil, lakes, and other glacial landforms, and therefore are assigned to the Central Minnesota region.

- ↑ Ecological Classification System, Northern Minnesota and Ontario Peatlands Section

- ↑ Ecological Classification System, Tallgrass Aspen Parklands Province.

- ↑ Ecological Classification System, Red River Valley Section.

- ↑ Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot, p. 9 ("Bedrock Geology Map").

- ↑ Heinselman, Forest Sites, Bog Processes, and Peatland Types in the Glacial Lake Agassiz Region, Minnesota, p. 331.

- ↑ Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot, p. 174, 181.

- ↑ Heinselman, Forest Sites, Bog Processes, and Peatland Types in the Glacial Lake Agassiz Region, Minnesota, pp. 354-61; Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot, pp. 191-93.

- ↑ "Patterned peatlands near Ludlow Lookout, Northern Beltrami County, MN". Aerial photograph. USGS via Microsoft Research Maps. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, p. 223; Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot, pp. 110-11.

- ↑ "U.S. Wind Energy Projects — Minnesota". The American Wind Energy Association. Archived from the original on April 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ↑ "History". Jeffers Petroglyphs. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ↑ "Map". Wetlands Component Assessment Regions. National Resources Conservation Service , United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- 1 2 "Wetlands". Fact Sheets. Minnesota River Basin Data Center, Minnesota State University, Mankato. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Minnesota’s Geology, p. 222 (map).

- ↑ Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot, p. 110.

- ↑ Ecological Classification System, Paleozoic Plateau Section.

- ↑ Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot, p. 129-31.

- ↑ While Sansome places the north bank of the Minnesota River in this region, this article follows Ojakangas and Matsch in assigning the lowlands along the north bank to Southwest Minnesota, and the uplands to Central Minnesota. Compare regional map at Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot at p. 109, with Ojakanas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, at p. 222.

- ↑ Sansome, Minnesota Underfoot, p. 9 ("Bedrock Geologic Map").

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch, Minnesota’s Geology, p. 59.

- ↑ Ojakangas and Matsch attach the metropolitan area to Southeastern Minnesota. Minnesota’s Geology, p. 232 (map).

- ↑ Anoka Conservation District. "Geologic History of the Anoka Sandplain". Guide to Anoka County's Natural Resources. Anoka County. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ↑ Black, Robert F. (2005). "Chapter 10: St. Croix Dalles Interstate Park". Geology of Ice Age National Scientific Reserve of Wisconsin, NPS Scientific Monograph No. 2. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Jol, Harry M. (2006). "Interstate State Park, A Brief Geologic History". University of Wisconsin at Eau Claire. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

Sources

- Black, Robert F. (2005). "Chapter 10: St. Croix Dalles Interstate Park". Geology of Ice Age National Scientific Reserve of Wisconsin, NPS Scientific Monograph No. 2. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-12-15. (Date of webpage - 2005-04-01.)

- Chandler, Val W (2005-08-03). "A Geophysical Investigation of the Ely Greenstone Belt in the Soudan Area, 4-5" (PDF). Open File Report 05-1. Minnesota Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-28. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- "Ecological Classification System". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2007-12-15. (Date of webpage: 2005-04-29)

- "Geologic History of the Anoka Sandplain". Guide to Anoka County's Natural Resources. Anoka County Conservation District. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- Heinselman, Miron (1996). The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Ecosystem. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-2804-1.

- Heinselman, Miron L. (Autumn 1963). "Forest Sites, Bog Processes, and Peatland Types in the Glacial Lake Agassiz Region, Minnesota" (PDF). Ecological Monographs. Ecological Society of America. 33 (4): 327–374. doi:10.2307/1950750. JSTOR 1950750. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- Jirsa, Mark and Southwick, David. "Mineral Potential and Geology of Minnesota". Minnesota Geological Survey, University of Minnesota. 2003-12-01. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- Jol, Harry M. (2006-12-06). "Interstate State Park, A Brief Geologic History". University of Wisconsin at Eau Claire. Retrieved 2007-12-15. (Date of webpage = 2005-04-01.)

- Lusardi, B.A. (1997). "Quaternary Glacial Geology" (PDF). Minnesota at a Glance. Minnesota Geological Survey, University of Minnesota. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- "Minnesota". America’s Volcanic Past: Places. U.S.Geological Survey, Cascades Volcanic Observatory. Retrieved 2007-12-15. (Date of webpage: 2003-01-26.)

- "Minnesota Wind Energy Development". Wind Project Data Base. The American Wind Energy Association. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-12-15. Date of webpage: (2007-03-31.)

- Morey, G. B. (February 1999). "High-grade iron ore deposits of the Mesabi Range, Minnesota; product of a continental-scale Proterozoic ground-water flow system". Economic Geology. Society of Economic Geologists. 94 (1): 133–42. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.94.1.133.

- "Natural History - Minnesota's Geology". Minnesota Dept. of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-15. (Date of webpage: 2007.)

- Nute, Grace Lee (1950). Rainy River Country. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society.

- Ojakangas, Richard W.; Matsch, Charles L (1982). Minnesota's Geology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0953-5.

- "Patterned peatlands near Ludlow Lookout, Northern Beltrami County, MN". Aerial photograph. USGS via Microsoft Research Maps. Retrieved 2007-12-15. (Date of photograph: 1991-04-25.)

- Sansome, Constance Jefferson (1983). Minnesota Underfoot: A Field Guide to the State's Outstanding Geologic Features. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-89658-036-9.

- Townsend, Catherine L.; Figge, John T. (2002). "Dance of the Giant Continents". Northwest Origins. Burke Museum of History and Culture, University of Washington. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- Van Schmus, W. R.; Hinze, W. J. (May 1985). "The Midcontinent Rift System" (PDF). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Annual Reviews. 13: 348. Bibcode:1985AREPS..13..345V. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.13.050185.002021. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- Upham, Warren (1896). "The Glacial Lake Agassiz". Monographs of the United States Geological Survey. United States Geological Survey. XXV. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- Waters, Thomas F. (1977). The Streams and Rivers of Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0821-0.

- "Wetlands". Fact Sheets. Minnesota River Basin Data Center, Minnesota State University, Mankato. Retrieved 2007-12-15. (Date of webpage: 2004-11-15.)

- "Wetlands Component Assessment Regions". Map 9726. National Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2007-12-15. (Date of map: April 2007.)

- Wright, W. E. (1990). Geologic History of Minnesota Rivers. Minnesota Geological Survey, Educational Series 7. St. Paul: University of Minnesota. ISSN 0544-3083.