Amulet

An amulet is an object whose most important characteristic is the power ascribed to it to protect its owner from danger or harm.[1] Amulets are different from talismans as a talisman is believed to bring luck or some other benefit, though it can offer protection as well.[2] Amulets are often confused with pendants—charms that hang from necklaces—any given pendant may indeed be an amulet, but so may any other charm which purports to protect its owner from danger.

Potential amulets include gems, especially engraved gems, statues, coins, drawings, pendants, rings, plants, animals, and even words in the form of a magical spell or incantation to repel evil or bad luck.

The word "amulet" comes from the Latin amulētum; the earliest extant use of the term is in Pliny's Natural History, meaning "an object that protects a person from trouble".[1][3]

In cultures

Ancient Rome

Amulets were particularly prevalent in ancient Roman society, being the inheritor of the ancient Greek tradition, and inextricably linked to Roman religion and magic (see Magic in the Greco-Roman World). Amulets are usually outside of the normal sphere of religious experience though associations between certain gemstones and gods has been suggested, for example, Jupiter is represented on milky chalcedony, Sol on heliotrope, Mars on red jasper, Ceres on green jasper and Bacchus on amethyst.[4] Amulets are worn to imbue the wearer with the associated powers of the gods rather than for any reasons of piety. The intrinsic power of the amulet is also evident from others bearing inscriptions, such as vterfexix (utere fexix) or "good luck to the user."[5] Amulet boxes could also be used, such as the example from part of the Thetford treasure, Norfolk, UK, where a gold box intended for suspension around the neck was found to contain sulphur for its apotropaic qualities.[6]

China and Japan

In China, Taoist experts called fulu developed a special style of calligraphy that they said would be able to protect against evil spirits. The equivalent type of amulet in Japan is called an ofuda.

Abrahamic religions

In antiquity and the Middle Ages, most Jews, Christians and Muslims in the Orient believed in the protective and healing power of amulets or blessed objects. Talismans used by these peoples can be broken down into three main categories: talismans carried or worn on the body, talismans hung upon or above the bed of an infirm person, and medicinal talismans. This third category can be further divided into external and internal talismans. For example, an external amulet can be placed in a bath.

Jews, Christians, and Muslims have also at times used their holy books in a talisman-like manner in grave situations. For example, a bed-ridden and seriously ill person would have a holy book placed under part of the bed or cushion.[7]

Judaism

Amulets are plentiful in the Jewish tradition, with examples of Solomon-era amulets existing in many museums. Due to proscription of idols, Jewish amulets emphasize text and names — the shape, material or color of an amulet makes no difference. Examples of textual amulets include the Silver Scroll, circa 630 BCE, and the still contemporary mezuzah[8] and tefillin.[9] A counter-example, however, is the Hand of Miriam, an outline of a human hand. Another non-textual amulet is the Seal of Solomon, also known as the hexagram or Star of David. In one form. it consists of two intertwined equilateral triangles, and in this form it is commonly worn suspended around the neck to this day.

Another common amulet in contemporary use is the Chai (symbol)—(Hebrew: חַי "living" ḥay), which is also worn around the neck. Other similar amulets still in use consist of one of the names of God, such as ה (He), יה (YaH), or שדי (Shaddai), inscribed on a piece of parchment or metal, usually silver.[10]

During the Middle Ages, Maimonides and Sherira Gaon (and his son Hai Gaon) opposed the use of amulets and derided the "folly of amulet writers."[11] Other rabbis, however, approved the use of amulets.[12]

Rabbi and famous kabbalist Naphtali ben Isaac Katz ("Ha-Kohen," 1645–1719) was said to be an expert in the magical use of amulets. He was accused of causing a fire that broke out in his house and then destroyed the whole Jewish quarter of Frankfurt, and of preventing the extinguishing of the fire by conventional means because he wanted to test the power of his amulets; he was imprisoned and forced to resign his post and leave the city.[13]

Christianity

The Roman Catholic Church maintains that the legitimate use of sacramentals in its proper disposition is only encouraged by a firm faith and devotion in God, not through any magical or superstitious belief bestowed on the sacramental. In this regard, rosaries, scapular, medals and other devotional religious Catholic paraphernalia derive their power, not from the symbolism created by the object, rather by the faith of the believer in entrusting its power to God. While some Catholics may not fully appreciate this view, belief in pagan magic or polytheistic superstition through material in-animate objects are condemned by the Holy See.

Protestant denominations in general do not share in this belief, but other Christian Evangelicals sometimes advertise in television prayer clothes, or coins, and wallet reminders claiming to have intercessory powers on its bearer.

Lay Catholics are not permitted to perform solemn exorcisms but they can use holy water, blessed salt and other sacramentals such as the Saint Benedict medal or the crucifix for warding off evil.[14]

The crucifix, and the associated sign of the cross, is one of the key sacramentals used by Catholics to ward off evil since the time of the Early Church Fathers. The imperial cross of Conrad II (1024–1039) referred to the power of the cross against evil.[15]

A well-known amulet among Catholic Christians is the Saint Benedict medal which includes the Vade Retro Satana formula to ward off Satan. This medal has been in use at least since the 18th century and in 1742 it received the approval of Pope Benedict XIV. It later became part of the Roman Catholic ritual.[16]

Some Catholic sacramentals are believed to defend against evil, by virtue of their association with a specific saint or archangel. The scapular of St. Michael the Archangel is a Roman Catholic devotional scapular associated with Archangel Michael, the chief enemy of Satan. Pope Pius IX gave this scapular his blessing, but it was first formally approved under Pope Leo XIII.

The form of this scapular is somewhat distinct, in that the two segments of cloth that constitute it have the form of a small shield; one is made of blue and the other of black cloth, and one of the bands likewise is blue and the other black. Both portions of the scapular bear the well-known representation of the Archangel St. Michael slaying the dragon and the inscription "Quis ut Deus?" meaning "Who is like God?".[17]

Catholic saints have written about the power of holy water as a force that repels evil. Saint Teresa of Avila, a Doctor of the Church who reported visions of Jesus and Mary, was a strong believer in the power of holy water and wrote that she used it with success to repel evil and temptations.[18]

Spanish soldiers, especially Carlist units, wore a patch with an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the inscription detente bala ("stop, bullet").

Islam

Amulets, often in the form of triangular packages containing a sacred verse, were traditionally attached to the clothing of babies and young children in Central and West Asia to give them protection from forces such as the evil eye.[19][20] Triangular amulet motifs were often also woven into oriental carpets such as kilims. The carpet expert Jon Thompson explains that such an amulet woven into a rug is not a theme: it actually is an amulet, conferring protection by its presence. In his words, "the device in the rug has a materiality, it generates a field of force able to interact with other unseen forces and is not merely an intellectual abstraction."[21]

Another popular amulet used in Islamic folk culture to avert the evil gaze is the hamsa (meaning five) or "Hand of Fatima". The symbol is pre-Islamic, known from Punic times.[22]

Other cultures

Amulets vary considerably according to their time and place of origin. In many societies, religious objects serve as amulets, e.g. deriving from the ancient Celts, the clover, if it has four leaves, symbolizes good luck (not the Irish shamrock, which symbolizes the Christian Trinity).[23]

In Bolivia, the god Ekeko furnishes a standard amulet, to whom one should offer at least one banknote or a cigarette to obtain fortune and welfare.[24]

In certain areas of India, Nepal and Sri Lanka, it is traditionally believed that the jackal's horn can grant wishes and reappear to its owner at its own accord when lost. Some Sinhalese believe that the horn can grant the holder invulnerability in any lawsuit.[25]

The Native American movement of the Ghost Dance wore ghost shirts to protect them from bullets.

In the Philippines, amulets are called agimat or anting-anting. According to folklore, the most powerful anting-anting is the hiyas ng saging (directly translated as pearl or gem of the banana). The hiyas must come from a mature banana and only comes out during midnight. Before the person can fully possess this agimat, he must fight a supernatural creature called kapre. Only then will he be its true owner. During Holy Week, devotees travel to Mount Banahaw to recharge their amulets.[26]

Gallery

-

Scapular of Our Lady of Mount Carmel or "Brown Scapular"

-

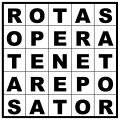

Sator Square, an ancient Roman amulet in the form of a palindromic word square

-

Amulet from Rajasthan

-

Ancient Roman amulet from Pompeii with a phallus

-

A mezuzah

-

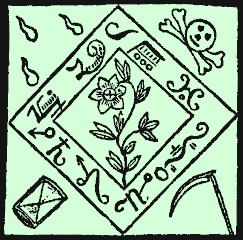

An amulet from the Black Pullet grimoire

-

Magical mirror with Zodiac signs

-

A talisman, American Indian medicine made by wolf skin, wool, mirrors, feathers, buttons and brass bell

-

Winti- amulet, an Afro-Surinamese traditional religion's amulet

-

Ancient Egyptian Taweret amulet, New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII, c. 1539–1292 BC

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Gonzalez-Wippler 1991, p. 1.

- ↑ Campo, Juan Eduardo, ed. (2009). "amulets and talismans". Encyclopedia of Islam. Encyclopedia of World Religions: Facts on File Library of Religion and Mythology. Infobase Publishing. pp. 40–1. ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- ↑ Guelden, Marlane (2007). Thailand: Spirits Among Us. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-981-261-075-1.

- ↑ Henig, Martin (1984). Religion in Roman Britain. London: B.T. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-1220-8.

- ↑ Collingwood, Robin G.; Wright, Richard P. (1991). Roman Inscriptions of Britain (RIB). Volume II, Fascicule 3. Stround: Alan Sutton. RIB 2421.56–8.

- ↑ Henig 1984, p. 187.

- ↑ Canaan, Tewfik (2004). "The Decipherment of Arabic Talismans". In Savage-Smith, Emilie. Magic and Divination in Early Islam. The Formation of the Classical Islamic World. 42. Ashgate. pp. 125–49. ISBN 978-0-86078-715-0.

- ↑ Kosior, Wojciech. ""It Will Not Let the Destroying [One] Enter". The Mezuzah as an Apotropaic Device according to Biblical and Rabbinic Sources, "The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture" 9 (1/2014), pp. 127-144". Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- ↑ Kosior, Wojciech. ""The Name of Yahveh is Called Upon You". Deuteronomy 28:10 and the Apotropaic Qualities of Tefillin in the Early Rabbinic Literature, "Studia Religiologica" 2 48/2015, pp. 143-154.". Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Judaica: Amulet.

- ↑ Guide to the Perplexed, 1:61; Yad, Tefillin 5:4.

- ↑ For example, Solomon ben Abraham Adret ("Rashba," 1235–1310, Spain) and Naḥmanides ("Ramban," 1194-1270, Spain). Ency. Jud., op. cit.

- ↑ Ency. Jud.: Katz, Naphtali ben Isaac. See also Naphtali Cohen#Biography.

- ↑ Scott, Rosemarie (2006). "Meditation 26: The Weapons of Our Warfare". Clean of Heart. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-9772234-5-9.

- ↑ Fahlbusch, Erwin; Lochman, Jan Milič; Mbiti, John; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Vischer, Lukas, eds. (1999). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Translator and English language editor: Bromiley, Geoffrey W. Boston: Eerdmans. p. 737. ISBN 978-0-8028-2413-4.

- ↑ Lea, Henry Charles (1896). "Chapter 12: Indulged Objects". A History of Auricular Confession and Indulgences in the Latin Church. Volume 3: Indulgences. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co. p. 520. OCLC 162534206.

- ↑ Ball, Ann (2003). Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices. Our Sunday Visitor. p. 520. ISBN 978-0-87973-910-2.

- ↑ Teresa of Ávila (2007). "Chapter 21: Holy Water". The Book of My Life. Translated by Starr, Mirabai. Boston: Shambhala Publications. pp. 238–41. ISBN 978-0-8348-2303-7.

- ↑ Erbek, Güran (1998). Kilim Catalogue No. 1. May Selçuk A. S. Edition=1st. pp. 4–30.

- ↑ "Kilim Motifs". Kilim.com. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ Thompson, Jon (1988). Carpets from the Tents, Cottages and Workshops of Asia. Barrie & Jenkins. p. 156. ISBN 0-7126-2501-1.

- ↑ Achrati, Ahmed (2003). "Hand and Foot Symbolism: From Rock Art to the Qur'an" (PDF). Arabica. 50 (4): 463–500 (see p. 477).

- ↑ Cleene, Marcel; Lejeune, Marie Claire (2003). Compendium of Symbolic and Ritual Plants in Europe. p. 178. ISBN 978-90-77135-04-4.

- ↑ Fanthorpe, R. Lionel; Fanthorpe, Patricia (2008). Mysteries and Secrets of Voodoo, Santeria, and Obeah. Mysteries and Secrets Series. 12. Dundurn Group. p. 183–4. ISBN 978-1-55002-784-6.

- ↑ Tennent, Sir, James Emerson (1999) [1861]. Sketches of the Natural History of Ceylon with Narratives and Anecdotes Illustrative of the Habits and Instincts of the Mammalia, Birds, Reptiles, Fishes, Insects, Including a Monograph of the Elephant and a Description of the Modes of Capturing and Training it with Engravings from Original Drawings (reprint ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 37. ISBN 978-81-206-1246-4.

- ↑ "The Agimat and Anting-Anting: Amulet and Talisman of the Philippines". amuletandtalisman.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24.

References

- Gonzalez-Wippler, Migene (1991). Complete Book Of Amulets & Talismans. Sourcebook Series. St. Paul, MN: Lewellyn Publications. ISBN 978-0-87542-287-9.

- Plinius, S.C. (1964) [c. 77-79]. Natural History. London.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amulets. |

| Look up amulet in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |