Howard Hawks

| Howard Hawks | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Howard Winchester Hawks May 30, 1896 Goshen, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died |

December 26, 1977 (aged 81) Palm Springs, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Film director, producer, screenwriter |

| Years active | 1916–1970 |

| Spouse(s) |

Athole Shearer (m. 1928; div. 1940) Slim Keith (m. 1941; div. 1949) Dee Hartford (m. 1953; div. 1960) |

| Children | 3, including Kitty Hawks |

Howard Winchester Hawks (May 30, 1896 – December 26, 1977) was an American film director, producer and screenwriter of the classic Hollywood era. Critic Leonard Maltin called him "the greatest American director who is not a household name."[1]

Hawks was a versatile director whose career included comedies, dramas, gangster films, science fiction, film noir, and westerns.[2] His most popular films include Scarface (1932), Bringing Up Baby (1938), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), To Have and Have Not (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Red River (1948), The Thing from Another World (1951), and Rio Bravo (1959). His frequent portrayals of strong, tough-talking female characters came to define a type—the "Hawksian woman".[2]

In 1942, Hawks was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director for Sergeant York, and in 1975 he was awarded an Honorary Academy Award as "a master American filmmaker whose creative efforts hold a distinguished place in world cinema."[3] His work has influenced some of the most popular and respected directors such as Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, John Carpenter, and Quentin Tarantino.

Early life and education

Family

Howard Winchester Hawks was born in Goshen, Indiana, the first-born child of Frank W. Hawks (1865–1950), a wealthy paper manufacturer, and his wife, Helen (née Howard; 1872–1952), the daughter of a wealthy industrialist. Hawks's family on his father's side were American pioneers and his ancestor John Hawks had emigrated from England to Massachusetts in 1630. The family eventually settled in Goshen and by the 1890s was one of the wealthiest families in the Midwest, due mostly to the highly profitable Goshen Milling Company.[4]:18–19

Hawks's maternal grandfather, C. W. Howard (1845–1916), had homesteaded in Neenah, Wisconsin in 1862 at age 17. Within 15 years he had made his fortune in the town's paper mill and other industrial endeavors.[4]:25 Frank Hawks and Helen Howard met in the early 1890s and married in 1895. Howard Hawks was the eldest of five children and his birth was followed by Kenneth Neil Hawks (August 12, 1899 – January 2, 1930), William Bellinger Hawks (January 29, 1901 – January 10, 1969), Grace Louise Hawks (October 17, 1903 – December 23, 1927) and Helen Bernice Hawks (1906 – May 4, 1911). In 1898, the family moved to Neenah, Wisconsin where Frank Hawks began working for his father-in-law's Howard Paper Company.[4]:27–29

Education

Between 1906 and 1909, the Hawks family began to spend more time in Pasadena, California during the cold Wisconsin winters in order to improve Helen Hawks's ill health. Gradually they began to spend only their summers in Wisconsin before permanently moving to Pasadena in 1910.[4]:31 The family settled in a house down the street from Throop Polytechnic Institute (which would eventually become California Institute of Technology), and the Hawks children began attending the school's Polytechnic Elementary School in 1907.[4]:34–35

Hawks was an average student at school and did not excel in sports, but by 1910 had discovered coaster racing, an early form of soapbox racing. In 1911, Hawks's youngest sibling Helen died suddenly of food poisoning.[4]:34–36[5] From 1910 to 1912, Hawks attended Pasadena High School. But in 1912, the Hawks family moved to nearby Glendora, California, where Frank Hawks owned orange groves. Hawks finished his junior year of high school at Citrus Union High School in Glendora and was then sent to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire from 1913 to 1914; his family's wealth may have influenced his acceptance to the elite private school. While in New England, Hawks often attended the theatres in nearby Boston. In 1914, Hawks returned to Glendora and graduated from Pasadena High School that year. That same year, Hawks was accepted to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where he majored in mechanical engineering and was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon. College friend Ray S. Ashbury remembered Hawks spending more of his time playing craps and drinking alcohol than studying, although Hawks was also known to be a voracious reader of popular American and English novels in college.[4]:36–39

In 1916, Hawks' grandfather, C.W. Howard, bought him a Mercer race car and Hawks began racing and working on his new car during the summer vacation in California. It was at this time that Hawks first met Victor Fleming, allegedly when the two men raced on a dirt track and caused an accident.[4]:39–42 Fleming had been an auto mechanic and early aviator when his old friend Marshall Neilan recommended him to film director Allan Dwan as a good mechanic. Fleming went on to impress Dwan by quickly fixing both his car and a faulty film camera and by 1916 had worked his way up to the position of cinematographer.[4]:39–42

Early film career

The meeting with Fleming led to Hawks's first job in the film industry, as a prop boy on the Douglas Fairbanks film In Again, Out Again (on which Fleming was employed as the cinematographer) for Famous Players-Lasky.[4]:42–44 According to Hawks, a new set needed to be built quickly when the studio's set designer was unavailable, so Hawks volunteered to do the job himself, much to Fairbanks's satisfaction. He was next employed as a prop boy and general assistant on an unspecified film directed by Cecil B. DeMille (Hawks never named the film in later interviews and DeMille made five films roughly in that time period). While still breaking into the film industry in the summer of 1916, Hawks made an unsuccessful attempt to transfer to Stanford University. He returned to Cornell that September, leaving in April 1917 when the United States entered World War I. Like many college students who joined the armed services during the war, he received a degree in absentia in 1918. Before Hawks was called for active duty, he took the opportunity to return to Hollywood and by the end of April 1917 was working on Cecil B. DeMille's The Little American. On this film he met and befriended the then 18-year-old slate boy James Wong Howe, who was to become one of Hollywood's most significant cinematographers.[4]:42–44 Hawks then worked on the Mary Pickford film The Little Princess, directed by Marshall Neilan. According to Hawks, Neilan did not show up to work one day, so the resourceful Hawks offered to direct a scene himself, to which Pickford consented.[4]:44[6]:74

Hawks began directing at age 21 after he and cinematographer Charles Rosher filmed a double exposure dream sequence with Mary Pickford. Hawks worked with Pickford and Neilan again on Amarilly of Clothes-Line Alley before joining the United States Army Air Service. Hawks's military records were destroyed in the 1973 Military Archive Fire, so the only account of his military service is his own. According to Hawks, he spent 15 weeks in basic training at the University of California in Berkeley where he was trained to be a squadron commander. When Pickford visited Hawks at basic training, his superior officers were so impressed by the appearance of the celebrity that they promoted him to flight instructor and sent him to Texas to teach new recruits. Bored by this work, Hawks attempted to secure a transfer during the first half of 1918 and was eventually sent to Fort Monroe, Virginia. The Armistice was signed in November of that year and Hawks was discharged as a Second Lieutenant without having seen active duty.[4]:45–47[5]

After the War, Hawks was eager to return to Hollywood. His brother, Kenneth Hawks, who had also served in the Air Force, graduated from Yale University in 1919 and the two of them moved to Hollywood together to pursue their careers. They quickly made friends with Hollywood insider (and fellow Ivy Leaguer) Allan Dwan, but Hawks landed his first important job when he used his family's wealth to loan money to studio head Jack L. Warner. Warner quickly paid back the loan and hired Hawks as a producer to "oversee" the making of a new series of one-reel comedies starring the Italian comedian Monty Banks. Hawks later stated that he personally directed "three or four" of the shorts, though no documentation exists to confirm the claim. The films were profitable, but Hawks soon left to form his own production company, using his family's wealth and connections to secure financing. Associated Producers was a joint venture between Hawks, Allan Dwan, Marshall Neilan and director Allen Holubar, with a distribution deal with First National. The company made 14 films between 1920 and 1923, with eight directed by Neilan, three by Dwan and three by Holubar.[4]:49–52 More of a "boy's club" than a production company, the four men gradually drifted apart and went their separate ways in 1923, by which time Hawks had decided that he wanted to direct rather than produce.[4]:56

Beginning in early 1920, Hawks lived in rented houses in Hollywood with the group of friends he was accumulating. This rowdy group of mostly macho, risk-taking men included his brother Kenneth Hawks, Victor Fleming, Jack Conway, Harold Rosson, Richard Rosson, Arthur Rosson and Eddie Sutherland. During this time, Hawks first met Irving Thalberg, the frail and sickly vice-President in charge of production at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Eventually many of the young men in this group would become successful at MGM under Thalberg. Hawks admired his intelligence and sense of story.[4]:57–58 Hawks also became friends with barn stormers and pioneer aviators at Rogers Airport in Los Angeles, getting to know men like Moye Stephens. In 1923, Famous Players-Lasky president Jesse Lasky was looking for a new Production Editor in the story department of his studio and Thalberg suggested Hawks.[5] Hawks accepted and was immediately put in charge of over forty productions, including several literary acquisitions by Joseph Conrad, Jack London and Zane Grey. Hawks worked on the scripts for all of the films produced, but had his first official screenplay credit in 1924 on Tiger Love.[4]:59–60 Hawks was the Story Editor at Famous Players (later Paramount Pictures) for almost two years, occasionally editing such films as Heritage of the Desert. Hawks signed a new one-year contract with Famous-Players in the fall of 1924, though he broke his contract to become a story editor for Thalberg at MGM, having secured a promise from Thalberg that he would make him a director within a year. In 1925, when Thalberg hesitated to follow through on his promise, Hawks broke his contract at MGM and left.[4]:60–63

Career as a film director

Silent films: 1925–1929

In October 1925, Sol Wurtzel, William Fox's studio superintendent at the Fox Film Corporation, invited Hawks to join his company with the promise of letting Hawks direct. Over the next three years, Hawks directed his first eight films (six silent, two "talkies").[5] A few months after joining Fox, Kenneth Hawks was also hired and eventually became one of Fox's top production supervisors.[4]:64–65 Hawks reworked the scripts of most of the films he directed without always taking official credit for his work. He also worked on the scripts for Honesty – The Best Policy in 1926[4]:71–74 and Joseph von Sternberg's Underworld in 1927, famous for being one of the first gangster films.[4]:76 In 1926, Hawks was introduced to Athole Shearer by his friend Victor Fleming, who was dating Athole's sister Norma Shearer at the time. Athole's first marriage to writer John Ward was unhappy. She and Hawks began dating throughout 1927, which led Shearer to ask Ward for a divorce in 1928. Shearer had a young son with Ward named Peter.[4]:78–81 At the same time, Kenneth Hawks began dating actress Mary Astor, while Hawks's youngest brother Bill began dating actress Bessie Love. Kenneth Hawks and Mary Astor eventually married in February 1928,[4]:81–83 while Bill Hawks and Bessie Love married in December 1929.[4]:106 After Hawks's mother refused to allow medical treatment because of her Christian Science beliefs, Hawks's sister Grace died of tuberculosis on December 23, 1927.[4]:82 Hawks and Athole Shearer married on May 28, 1928 and they honeymooned in Hawaii.[4]:95–96 Hawks's contract with Fox ended in May 1929 and he never again signed a long-term contract with a major studio but managed to remain an independent producer-director for the rest of his long career.[5] In October 1929, Hawks and Shearer had their first child, David Hawks.[4]:105

The Road to Glory (1926)

Hawks's first film The Road to Glory was based on a 35-page treatment that Hawks wrote and is one of only two Hawks works that are lost films. The film starred May McAvoy as a young woman who is gradually going blind and tries to spare the two men in her life from the burden of her illness. The two men are her boyfriend Rockliffe Fellowes and her father Ford Sterling, with Leslie Fenton playing the greedy rich man whom she agrees to live with in order to get away from her father and lover. The film contained religious iconography and messages that would never again be seen in a Hawks film. It was shot from December 1925 to January 1926 and premiered in April. It received good reviews from film critics. In later interviews, Hawks said, "It didn't have any fun in it. It was pretty bad. I don't think anybody enjoyed it except a few critics." Hawks was dissatisfied with the film after being certain that dramatic films would establish his reputation, but realized what he had done wrong when Sol Wurtzel told Hawks, "Look, you've shown you can make a picture, but for God's sake, go out and make entertainment."[4]:65–68

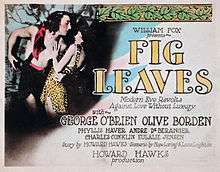

Fig Leaves (1926)

Immediately after completing The Road to Glory, Hawks began writing his next film, Fig Leaves, his first (and, until 1935, only) comedy. The film portrays a married couple by juxtaposing them in the Garden of Eden and in modern New York City. The Garden of Eden humorously depicts Adam and Eve awoken by a Flintstones-like coconut alarm clock and Adam reading the morning news on giant stone tablets. In the modern day, the biblical serpent is replaced by Eve's gossiping neighbor and Eve becomes a sexy flapper and fashion model when Adam is at work. The film starred George O'Brien as Adam and Olive Borden as Eve and received positive reviews, particularly for the art direction and costume designs. It was released in July 1926 and was Hawks's first hit as a director. Although he mainly dismissed his early work, Hawks praised this film in later interviews.[4]:69–71

Paid to Love (1927)

Paid to Love is notable in Hawks's filmography as being the only time that he made a highly stylized, experimental film. He attempted to imitate the style of German film director F. W. Murnau, who had recently made The Last Laugh and Sunrise and was the most critically acclaimed director in Hollywood. Hawks's film includes atypical tracking shots, expressionistic lighting and stylistic film editing that was inspired by German Expressionist cinema. In a later interview, Hawks commented "It isn't my type of stuff, at least I got it over in a hurry. You know the idea of wanting the camera to do those things: Now the camera's somebody's eyes." Hawks worked on the script with Seton I. Miller, with whom he would go on to collaborate on seven more films. The film stars George O'Brien as the introverted Crown Prince Michael, William Powell as his happy-go-lucky brother and Virginia Valli as Michael's flapper love interest Dolores. The characters played by Valli and O'Brien anticipate those found in later films by Hawks: a sexually aggressive showgirl, who is an early prototype of the "Hawksian woman", and a shy man disinterested in sex, found in later roles played by Cary Grant and Gary Cooper. Paid to Love was completed by September 1926, but remained unreleased until July 1927, when it was financially unsuccessful.[4]:72–75

Cradle Snatchers (1927)

Cradle Snatchers was based on a 1925 hit stage play by Russell G. Medcraft and Norma Mitchell about three unhappy, middle-aged housewives who teach their adulterous husbands a lesson by starting affairs with college-aged young men during the jazz age. The film starred Louise Fazenda, Dorothy Phillips and Ethel Wales and was shot in early 1927. The film was released in May 1927 and was a minor hit. For many years it was believed to be a lost film until film director Peter Bogdanovich discovered a print in 20th Century Fox's film vaults, although the print was missing part of reel three and all of reel four.[4]:76–78

Fazil (1928)

In March 1927, Hawks signed a new one-year, three-picture contract with Fox and was assigned to direct Fazil, based on the play L'Insoumise by Pierre Frondaie. Hawks again worked with Seton Miller on the script about a Middle Eastern prince who has an affair with a Parisienne showgirl and cast Charles Farrell as the prince and Greta Nissen as Fabienne. Hawks went both over schedule and over budget on the film, which began a rift between him and Sol Wurtzel that would eventually lead to Hawks leaving Fox. The film was finished in August 1927, though it was not released until June 1928.[4]:84–86

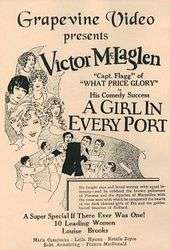

A Girl in Every Port (1928)

A Girl in Every Port is considered by film scholars to be the most important film of Hawks's silent career. It is the first of his films to utilize many of the Hawksian themes and characters that would define much of his subsequent work. It was his first "love story between two men," with two men bonding over their duty, skills and careers, who consider their friendship to be more important than their relationships with women. Hawks wrote the original story and developed the screenplay with James Kevin McGuinness and Seton Miller. In the film Victor McLaglen and Robert Armstrong play two merchant seamen who are archrivals when it comes to women, with McLaglen constantly finding Armstrong's tattoo on the women that he is attempting to seduce. Eventually the two rivals become friends. Louise Brooks plays the cabaret singer with whom the two men fall in love. The film was shot from October to December 1927 and released in February 1928. It was successful in the US, and a hit in Europe where Louise Brooks was developing a cult following.[4]:86–91 In France, Henri Langlois called Hawks "the Gropius of the cinema" and Swiss novelist and poet Blaise Cendrars said that the film "definitely marked the first appearance of contemporary cinema."[4]:92 Hawks went over budget once again with this film, though, and his relationship with Sol Wurtzel deteriorated. After an advance screening that received positive reviews, Wurtzel told Hawks, "This is the worst picture Fox has made in years."[4]:91

The Air Circus (1928)

The Air Circus is Hawks' first film centered around aviation, one of his early passions. In 1928, Charles Lindbergh was the world's most famous person and Wings was one of the most popular films of the year. Wanting to capitalize on the country's aviation craze, Fox immediately bought Hawks's original story for The Air Circus, a variation of the male friendship plot of A Girl in Every Port about two young pilots. Officially, the original story is credited to Graham Baker and Andrew Bennison, while the screenplay was written by Seton Miller and Norman Z. McLeod. In the film, Arthur Lake and David Rollins play two eager young pilots at flight school who compete over their flight instructor's aviatrix sister, played by Sue Carol. The film was shot from April to June 1928, but Fox ordered an additional 15 minutes of dialogue footage in order that the film could compete with the new "talkies" being released. Hawks hated the new dialogue written by Hugh Herbert and he refused to participate in the re-shoots. The film was released in September 1928 and was a moderate hit. It is one of two films directed by Hawks that are lost films.[4]:92–94

Trent's Last Case (1929)

Trent's Last Case is an adaptation of British author E. C. Bentley's 1913 novel of the same name, which had already been adapted for cinema in England in 1920. Hawks considered the novel to be "one of the greatest detective stories of all time" and was eager to make it his first sound film. He cast Raymond Griffith in the lead role of Phillip Trent. Griffith's throat had been damaged by poison gas during World War I and his voice was a hoarse whisper, prompting Hawks to later state, "I thought he ought to be great in talking pictures because of that voice." However, after shooting only a few scenes, Fox shut Hawks down and ordered him to make a silent film, both because of Griffith's voice and because they only owned the legal rights to make a silent film. The film did have a musical score and synchronized sound effects, but no dialogue. Due to the failing business of silent films, it was never released in the US and only briefly screened in England where film critics hated it. The film was believed lost until the mid-1970s and was screened for the first time in the US at a Hawks retrospective in 1974. Hawks was in attendance of the screening and attempted to have the only print of the film destroyed.[4]:97–101

Early sound films: 1930–1934

By 1930, Hollywood was in upheaval over the coming of "talkies" and the careers of many actors and directors were ruined. Hollywood studios were recruiting stage actors and directors that they believed were better suited for sound films. After having worked in the industry for 14 years and directed many financially successful films, Hawks found himself having to prove himself an asset to the studios once again. Leaving Fox on sour terms didn't help his reputation, but Hawks was one of the few people in Hollywood who never backed down from fights with studio heads. After several months of unemployment, Hawks renewed his career with his first sound film in 1930.[4]:102

On January 2, 1930, Hawks's brother Kenneth Hawks died while shooting the film Such Men Are Dangerous.[4]:106–109 Kenneth's career as a director had been gathering momentum after his debut film Big Time in 1929. This sound film starred Lee Tracy and Mae Clarke and was an early example of the "fast-talking" sound films that would later become one of Howard Hawks's signatures.[4]:100–101 Such Men Are Dangerous was based on the life Alfred Lowenstein, a Belgian captain who either jumped or fell out of his plane in 1928. On January 2, Kenneth Hawks and his crew flew three aircraft (two with cameras, one with a stunt actor) over Santa Monica Bay when the two camera aircraft crashed into each other, killing 10 men. The crash was the first major on-set accident in Hollywood history and made national news. Mary Astor kept her distance from the Hawks family after Kenneth's death.[4]:106–110

The Dawn Patrol (1930)

Hawks's first all sound film was The Dawn Patrol, based on an original story by John Monk Saunders and (unofficially) Hawks. Saunders was a flight instructor during World War I and had written Wings. He was considered one of the most talented writers in Hollywood and was often compared to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. Accounts vary on who came up with the idea of the film, but Hawks and Saunders developed the story together and tried to sell it to several studios before First National agreed to produce it.[4]:102–105 Saunders received solo screen credit for the original story and won an Academy Award for Best Story in 1930. The screenplay was written by Hawks, Seton Miller and Dan Totheroh and starred Richard Barthelmess and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. Shooting began in late February 1930, about the same time that Howard Hughes was finally finishing his epic World War I aviation epic Hell's Angels, which had been in production since September 1927. Shrewdly, Hawks began to hire many of the aviation experts and cameramen that had been employed by Hughes, including Elmer Dyer, Harry Reynolds and Ira Reed. When Hughes found out about the rival film, he did everything he could to sabotage The Dawn Patrol. He harassed Hawks and other studio personal, hired a spy that was quickly caught and finally sued First National for copyright infringement. Hughes eventually dropped the lawsuit in late 1930—he and Hawks had become good friends during the legal battle. In the film, Barthelmess and Fairbanks play two Royal Flying Corps pilots during World War I who deal with the pressure of wartime combat and constant death by drinking and fighting with their commanding officer. Filming was finished in late May 1930 and it premiered in July, setting a first-week box office record at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York. The film became one of the biggest hits of 1930.[4]:111–115

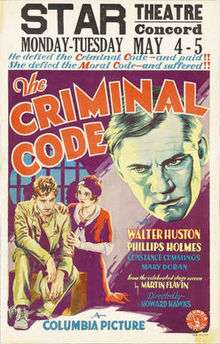

The Criminal Code (1931)

Hawks did not get along with Warner Brothers executive Hal B. Wallis and his contract allowed him to be loaned out to other studios. Hawks took the opportunity to accept a directing offer from Harry Cohn at Columbia Pictures: The Criminal Code, based on a successful play by Martin Flavin. Hawks and Seton Miller worked on the script with Flavin for a month and filming began in September 1930. The film starred Walter Huston, Phillips Holmes, Constance Cummings and Boris Karloff. Huston plays a prison warden who wants to reform the conditions of the inmates and Holmes plays a wrongly convicted prisoner who learns about the "code" of not ratting on other inmates. Hawks called Huston "the greatest actor I ever worked with".[4]:118–119 Hawks also worked with his old friend James Wong Howe for the first time as a cinematographer. The film opened in January 1931 and was a hit. The film was banned in Chicago, though, and the experience of censorship which would continue in his next film project.[4]:120–121

Scarface (1932)

In 1930, Howard Hughes hired Hawks to direct Scarface, a gangster film loosely based on the life of Chicago mobster Al Capone. The film starred Paul Muni in the title role, with memorable supporting performances from George Raft, Boris Karloff, and Osgood Perkins. The film was completed in September 1931, but the censorship of the Hays Code prevented it from being released as Hawks and Hughes had originally intended. The two men fought, negotiated and made compromises with the Hays Office for over a year, until the film was eventually released in 1932, after such other pivotal early gangster films as The Public Enemy and Little Caesar. Scarface was the first film in which Hawks worked with screenwriter Ben Hecht, who became a close friend and collaborator for 20 years.[5]

The Crowd Roars (1932)

After filming was complete on Scarface, Hawks left Hughes to fight the legal battles and returned to First National to fulfill his contract, this time with producer Darryl F. Zanuck. For his next film, Hawks wanted to make a film about his childhood passion: car racing. The Crowd Roars is loosely based on the play The Barker: A Play of Carnival Life by Kenyon Nicholson. Hawks developed the script with Seton Miller for their eighth and final collaboration and the script was by Miller, Kubec Glasmon, John Bright and Niven Busch. The film starred James Cagney, Eric Linden, Joan Blondell and Ann Dvorak. In the film, Cagney plays a race car driver who tries to "protect" his younger brother Linden, who is also a driver, from being distracted by his girlfriend, Blondell. At the same time, Cagney must hide his own neurotic girlfriend, played by Dvorak, from his younger brother. Blondell and Dvorak were initially cast in each other's roles but swapped after a few days of shooting. Shooting began on December 7, 1931 at Legion Ascot Speedway and wrapped on February 1, 1932. Hawks used real race car drivers in the film, including the 1930 Indianapolis 500 winner Billy Arnold.[4]:156–162 The film was released in March and became a hit.[4]:172

Tiger Shark (1932)

Later in 1932, he directed Tiger Shark starring Edward G. Robinson as a tuna fisherman. In these early films, Hawks established the prototypical "Hawksian Man", which film critic Andrew Sarris described as "upheld by an instinctive professionalism."[5] Tiger Shark demonstrated Hawks's ability to incorporate touches of humor into dramatic, tense, and even tragic story lines.[4]:172

Today We Live (1933) In 1933, Hawks signed a three-picture deal at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, the first of which was Today We Live in 1933, starring Joan Crawford and Gary Cooper. This World War I film was based on a short story by author William Faulkner, with whom Hawks would remain friends for over 20 years.[4]:173–187

Hawks's next two films at MGM were the boxing drama The Prizefighter and the Lady and the bio-pic Viva Villa!, starring Wallace Beery as Mexican Revolutionary leader Pancho Villa. Studio interference on both films led Hawks to walk out on his MGM contract without completing either film himself.[5]

Later sound films

In 1934, Hawks went to Columbia Pictures to make his first screwball comedy, Twentieth Century, starring John Barrymore and Hawks's distant cousin Carole Lombard. It was based on a stage play by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur and, along with Frank Capra's It Happened One Night (released the same year), is considered to be the defining film of the screwball comedy genre. In 1935, Hawks made Barbary Coast with Edward G. Robinson and Miriam Hopkins. In 1936, he made the aviation adventure Ceiling Zero with James Cagney and Pat O'Brien. Also in 1936, Hawks began filming Come and Get It, starring Edward Arnold, Joel McCrea, Frances Farmer and Walter Brennan. But he was fired by Samuel Goldwyn in the middle of shooting and the film was completed by William Wyler.[5]

In 1938, Hawks made the screwball comedy Bringing Up Baby for RKO Pictures. It starred Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn and has been called "the screwiest of the screwball comedies" by film critic Andrew Sarris. Grant plays a near-sighted paleontologist who suffers one humiliation after another due to the lovestruck socialite played by Hepburn.[5] Bringing Up Baby was a box office flop when initially released and, subsequently, RKO fired Hawks due to extreme losses; however, the film has become regarded as one of Hawks's masterpieces.[7] Hawks followed this with the aviation drama Only Angels Have Wings, again starring Cary Grant and made in 1939 for Columbia Pictures. It also starred Jean Arthur, Thomas Mitchell, Rita Hayworth and Richard Barthelmess.[5]

In 1940, Hawks returned to the screwball comedy genre with His Girl Friday, starring Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell. The film was an adaptation of the hit Broadway play The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur,[5] which had already been made into a film in 1931 and had also been reworked by the same screenwriters and transplanted to Rudyard Kipling's India for Gunga Din in 1939.[8] In 1941, Hawks made Sergeant York, starring Gary Cooper as a pacifist farmer who becomes a decorated World War I soldier. This was the highest-grossing film of 1941 and won two Academy Awards (Best Actor and Best Editing), as well as earning Hawks his only nomination for Best Director. Later that year, Hawks worked with Cooper again for Ball of Fire, which also starred Barbara Stanwyck. The film was written by Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett and is a playful take on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Cooper plays a sheltered, intellectual linguist who is writing an encyclopedia with six other scientists, and hires street-wise Stanwyck to help them with modern slang terms. In 1941, Hawks began work on the Howard Hughes-produced (and later directed) film The Outlaw, based on the life of Billy the Kid and starring Jane Russell. Hawks completed initial shooting of the film in early 1941, but due to perfectionism and battles with the Hollywood Production Code, Hughes continued to re-shoot and re-edit the film until 1943, when it was finally released with Hawks uncredited as director.[5]

After making the World War II film Air Force in 1943 starring John Garfield, Hawks did two films with real-life lovers Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. To Have and Have Not, made in 1944, stars Bogart, Bacall and Walter Brennan and is based on a novel by Ernest Hemingway. Hawks was a close friend of Hemingway and made a bet with the author that he could make a good film out of Hemingway's "worst book." Hawks, William Faulkner and Jules Furthman collaborated on the script about an American fishing boat captain working out of French Martinique in the Caribbean and various situations of espionage after the Fall of France in 1940. Bogart and Bacall fell in love on the set of the film and married soon afterwards. Hawks reteamed with the newlyweds in 1946 with The Big Sleep, based on the Philip Marlowe detective novel by Raymond Chandler.[5]

In 1948, Hawks made Red River, an epic western reminiscent of Mutiny on the Bounty starring John Wayne and Montgomery Clift in his first film. Later that year, Hawks remade his earlier film Ball of Fire as A Song Is Born, this time starring Danny Kaye and Virginia Mayo. This version follows the same plot but pays more attention to popular jazz music and includes such jazz legends as Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, and Benny Carter playing themselves. In 1949, Hawks reteamed with Cary Grant in the screwball comedy I Was a Male War Bride, also starring Ann Sheridan.[5]

In 1951, Hawks produced, and some believe essentially directed, a science-fiction film, The Thing from Another World. Director John Carpenter stated: "And let's get the record straight. The movie was directed by Howard Hawks. Verifiably directed by Howard Hawks. He let his editor, Christian Nyby, take credit. But the kind of feeling between the male characters—the camaraderie, the group of men that has to fight off the evil—it's all pure Hawksian."[9][10] He followed this with the 1952 western film The Big Sky, starring Kirk Douglas. Later in 1952, Hawks work with Cary Grant for the fifth and final time in the screwball comedy Monkey Business, which also starred Marilyn Monroe and Ginger Rogers. Grant plays a scientist (reminiscent of his character in Bringing up Baby) who creates a formula that increases his vitality. Film critic John Belton called the film Hawks's "most organic comedy."[5] Hawks's third film of 1952 was a contribution to the omnibus film O. Henry's Full House, which includes short stories by the writer O. Henry made by various directors.[11] Hawks's short film The Ransom of Red Chief starred Fred Allen, Oscar Levant and Jeanne Crain.[6]:xxvi

In 1953, Hawks made Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which featured Marilyn Monroe famously singing "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend." The film starred Monroe and Jane Russell as two gold-digging, cabaret-performer best friends that many critics argue is the only female version of his celebrated "buddy film" genre that he made. In 1955, Hawks shot a film atypical within the context of his other work, Land of the Pharaohs, which is a sword-and-sandal epic about ancient Egypt that stars Jack Hawkins and Joan Collins. The film was Hawks's final collaboration with longtime friend William Faulkner before the author's death. In 1959, Hawks worked with John Wayne in Rio Bravo, also starring Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson and Walter Brennan as four lawmen "defending the fort" of their local jail in which a local criminal is awaiting a trial while his family attempt to break him out. Film critic Robin Wood has said that if he "were asked to choose a film that would justify the existence of Hollywood ... it would be Rio Bravo."[5]

In 1962, Hawks made Hatari!, again with John Wayne, who plays a big-game hunter in Africa. In 1964, Hawks made his final comedy, Man's Favorite Sport?, starring Rock Hudson (since Cary Grant felt he was too old for the role) and Paula Prentiss. Hawks then returned to his childhood passion for car races with Red Line 7000 in 1965, featuring a young James Caan in his first leading role. Hawks's final two films were both Western remakes of Rio Bravo starring John Wayne. In 1966, Hawks directed El Dorado, starring Wayne, Robert Mitchum and Caan, which was released the following year. He then made Rio Lobo, with Wayne in 1970.[5]

Personal life

Hawks was married three times: to actress Athole Shearer, sister of Norma Shearer, from 1928–40; to socialite Slim Keith from 1941–49; and to actress Dee Hartford from 1953–60.

Hawks died on December 26, 1977, at the age of 81, from complications arising from a fall when he tripped over his dog several weeks earlier at his home in Palm Springs, California. He was working with his last protege discovery at the time, Larraine Zax.[12]

Style

Hawks was a versatile director whose career includes comedies, dramas, gangster films, science fiction, film noir, and Westerns. Hawks's own functional definition of what constitutes a "good movie" is characteristic of his no-nonsense style: "Three great scenes, no bad ones."[6]:63[2] Hawks also defined a good director as "someone who doesn't annoy you."[13]

While Hawks was not sympathetic to feminism, he popularized the Hawksian woman archetype, which, according to Naomi Wise, has been cited as a prototype of the post-feminist movement.[14]

Orson Welles in an interview with Peter Bogdanovich said of Howard Hawks, in comparison with John Ford, that "Hawks is great prose; Ford is poetry."[15]

Despite Hawks's work in a variety of Hollywood genres, he still retained an independent sensibility. Film critic David Thomson wrote of Hawks: "Far from being the meek purveyor of Hollywood forms, he always chose to turn them upside down. To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep, ostensibly an adventure and a thriller, are really love stories. Rio Bravo, apparently a Western – everyone wears a cowboy hat – is a comedy conversation piece. The ostensible comedies are shot through with exposed emotions, with the subtlest views of the sex war, and with a wry acknowledgment of the incompatibility of men and women."[16] David Boxwell argues that the filmmaker's body of work "has been accused of a historical and adolescent escapism, but Hawks' fans rejoice in his oeuvre's remarkable avoidance of Hollywood's religiosity, bathos, flag-waving, and sentimentality.[17]

Legacy

Hawks's directorial style and the use of natural, conversational dialogue in his films are cited as major influences on many noted filmmakers, including Robert Altman, John Carpenter, and Quentin Tarantino. His work is also admired by many notable directors including Peter Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese, François Truffaut, Michael Mann[18] and Jacques Rivette.[19] Jean-Luc Godard called him "the greatest American artist."[18][20] Critic Leonard Maltin labeled Hawks "the greatest American director who is not a household name."[1] Andrew Sarris in his influential book of film criticism The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929–1968 included Hawks in the "pantheon" of the 14 greatest film directors who had worked in the United States.[21] Brian De Palma dedicated his version of Scarface to Hawks and Ben Hecht.[22] Hawks was nicknamed "The Gray Fox" by members of the Hollywood community, thanks to his prematurely gray hair.[4][23]

Hawks was venerated by French critics associated with Cahiers du cinéma, who intellectualized his work in a way that Hawks himself found moderately amusing (his work was promoted in France by The Studio des Ursulines cinema), and though he was not taken seriously by British critics of the Sight and Sound circle at first, other independent British writers, such as Robin Wood, admired his films. Wood named the Hawks's Rio Bravo as his top film of all time.[24]

In the 2012 Sight & Sound's Greatest Film Poll, six of the films that Hawks had directed were in the Critics' Top 250 Films: Rio Bravo (number 63), Bringing Up Baby (number 110), Only Angels Have Wings (number 154), His Girl Friday (number 171), The Big Sleep (number 202) and Red River (number 235)[25]

Awards

He was nominated for Academy Award for Best Director in 1942 for Sergeant York,[26] but he received his only Oscar in 1975 as an Honorary Award from the Academy.[27]

His films The Big Sleep,[28] Bringing Up Baby, His Girl Friday, Red River, Rio Bravo, Scarface,[29] Sergeant York, The Thing from Another World and Twentieth Century were rated "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress and inducted into the National Film Registry.[30]

Bringing Up Baby (1938) was listed number 97 on the American Film Institute's AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies.[31] On the AFI's AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs Bringing Up Baby was listed number 14, His Girl Friday (1940) was listed number 19 and Ball of Fire (1941) was listed number 92.[32]

For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Howard Hawks has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1708 Vine Street.[33]

Filmography

References

- 1 2 Crouse, Richard (October 2005). Reel Winners: Movie Award Trivia. Dundurn. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-55002-574-3. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Wheeler Winston Dixon and Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, A Short History of Film (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press) p. 99—101. ISBN 978-0-8135-4270-6.

- ↑ "Awards." IMDb. Retrieved: July 1, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 McCarthy, Todd (1997). Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3740-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Wakeman, John (1987). World Film Directors, Volume 1, 1890–1945. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company. pp. 446–451. ISBN 978-0-8242-0757-1.

- 1 2 3 Breivold, Scott (February 2006). Howard Hawks: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-833-3. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Laham, Nicholas (May 2009). Currents of Comedy on the American Screen: How Film and Television Deliver Different Laughs for Changing Times. McFarland. pp. 27–29. ISBN 9780786442645. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Moss, Marilyn Ann (August 2015). Giant: George Stevens, a Life on Film. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780299204341. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Carpenter, John (speaker). "Hidden Values: The movies of the '50s(Television production).' Turner Classic Movies, April 9, 2001. Retrieved: January 4, 2009.

- ↑ Fuhrmann, Henry. "A 'Thing' to his credit." Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1997. Retrieved: April 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Review: 'O. Henry's Full House'". Variety. 31 Dec 1951. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "Howard Hawks, age 81 dies in Palm Springa". Frederick Daily Leader. 28 Dec 1977. Retrieved 30 Sep 2012.

- ↑ Farr, John (5 Apr 2013). "Genius Uncovered: The Film Legacy of Howard Hawk". Huffington Post. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Hillier, Jim; Wollen, Peter, eds. (April 1997). Howard Hawks: American Artist. British Film Institute. pp. 111–119. ISBN 978-0-85170-593-4.

- ↑ Bogdanovich, Peter. "The Southener." Indiewire.com, January 18, 2011. Retrieved: July 1, 2016.

- ↑ Thomson, David (November 1994). A Biographical Dictionary of Film (3 ed.). Knopf. p. 322. ISBN 9780679755647.

- ↑ Boxwell, David. "Howard Hawks." Senses of Cinema, May 2002. Retrieved: July 1, 2016.

- 1 2 Horne, Philip. "Howard Hawks: The king of American cool." The Daily Telegraph (London), December 29, 2010. Retrieved: July 1, 2016.

- ↑ Rivette, Jacques. "The Genius of Howard Hawks." dvdbeaver.com. Retrieved: July 1, 2016.

- ↑ Brody, Richard. "Jean-Luc Goddard: Bravo, 'RIO BRAVO'." The New Yorker, December 2, 2011. Retrieved: July 1, 2016.

- ↑ Sarris, Andrew (August 1996). The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929–1968. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80728-2. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Hutchinson, Sean (17 Dec 2015). "17 Things You Might Not Know About 'Scarface'". Mental Floss. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Fuller, Samuel (November 2002). A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting, and Filmmaking. Knopf. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-375-40165-7. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Howell, Peter. "Rio Bravo tops late critic Robin Wood's Top 10 list." Toronto Star, January 8, 2010. Retrieved: July 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Critics' top 100." BFI. Retrieved: July 1, 2016.

- ↑ "The 14th Academy Awards 1942". Oscars. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "The 47th Academy Awards 1975". Oscars. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "Films Selected to the National Film Registry 1997". New to the National Film Registry. Library of Congress. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. National Film Registry – Titles". Carnagie Mellon University. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Greatest American Movies of All Time". American Film Institute. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Funniest American Movies Of All Time". American Film Institute. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "Howard Hawks". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

Further reading

- Branson, Clark. Howard Hawks, A Jungian Study. Santa Barbara, California: Garland-Clarke Editions, 1987. ISBN 978-0-88496-261-8.

- Liandrat-Guigues, Suzanne. Red River. London: BFI Publishing, 2000. ISBN 978-0-85170-819-5.

- McBride, Joseph. Hawks on Hawks. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0-520-04552-1.

- McBride, Joseph (ed). Focus on Howard Hawks. New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1972. ISBN 978-0-13-384271-5.

- Pippin, Robert B. Hollywood Westerns and American Myth: The Importance of Howard Hawks and John Ford for Political Philosophy. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-300-14577-9.

- Wood, Robin. Howard Hawks. London: Secker & Warburg, 1968. ISBN 978-0-85170-111-0. London: British Film Institute, 1981, revised with addition of chapter "Retrospect". ISBN 978-0-85170-111-0. New Edition, Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-8143-3276-4.

- Wood, Robin. Rio Bravo. London: BFI Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-0-85170-966-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Howard Hawks. |

- Howard Hawks at the Internet Movie Database

- Howard Hawks at the TCM Movie Database

- Bibliography of books and articles about Hawks via UC Berkeley Media Resources Center

- Profile at Senses of Cinema

- BBC interview

- Howard Hawks at Find a Grave

- Howard Hawks papers, MSS 1404 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University