Legionnaires' disease

| Legionnaires' disease | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | legionellosis,[1] Legion fever |

| |

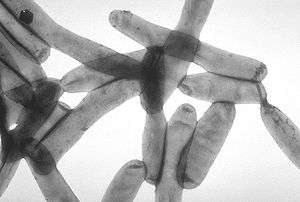

| Transmission electron microscopy image of L. pneumophila, responsible for over 90% of Legionnaires' disease cases[2] | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, pulmonology |

| ICD-10 | A48.1, A48.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 482.84 |

| DiseasesDB | 7366 |

| MedlinePlus | 000616 |

| eMedicine | med/1273 |

| MeSH | D007876 |

| Orphanet | 549 |

Legionnaires' disease is a form of atypical pneumonia caused by any type of Legionella bacteria.[3] Signs and symptoms include cough, shortness of breath, high fever, muscle pains, and headaches.[4] Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea may also occur.[1] This often begins two to ten days after being exposed.[4]

The bacterium is found naturally in fresh water. It can contaminate hot water tanks, hot tubs, and cooling towers of large air conditioners. It is usually spread by breathing in mist that contains the bacteria. It can also occur when contaminated water is aspirated. It typically does not spread directly between people and most people who are exposed do not become infected.[5] Risk factors for infection include older age, history of smoking, chronic lung disease, and poor immune function.[6] It is recommended that those with severe pneumonia and those with pneumonia and a recent travel history be tested for the disease.[7] Diagnosis is by a urinary antigen test and sputum culture.[8]

There is no vaccine. Prevention depends on good maintenance of water systems.[9] Treatment of Legionnaires' disease is with antibiotics.[10] Recommended agents include fluoroquinolones, azithromycin, or doxycycline.[11] Hospitalization is often required.[7] About 10% of those who are infected die.[10]

The number of cases that occur globally is not known. It is estimated that Legionnaires' disease is the cause of between two and nine percent of pneumonia cases that occur in the community.[1] There are an estimated 8,000 to 18,000 cases a year in the United States that require hospitalization.[12] Outbreaks of disease account for a minority of cases.[1][13] While it can occur any time of the year it is more common in the summer and fall.[12] The disease is named after the outbreak where it was first identified, the 1976 American Legion convention in Philadelphia.[14]

Signs and symptoms

The length of time between exposure to the bacteria and the appearance of symptoms is generally two to 10 days, but can rarely extend to as much as 20 days.[15] For the general population, among those exposed between 0.1 and 5% develop disease, while among those in hospital between 0.4 and 14% develop disease.[15]

Those with Legionnaires' disease usually have fever, chills, and a cough, which may be dry or may produce sputum. Almost all with Legionnaires' experience fever, while approximately half have cough with sputum, and one third cough up blood or bloody sputum. Some also have muscle aches, headache, tiredness, loss of appetite, loss of coordination (ataxia), chest pain, or diarrhea and vomiting.[16] Up to half of those with Legionnaires' have gastrointestinal symptoms, and almost half have neurological symptoms,[15] including confusion and impaired cognition.[17] "Relative bradycardia" may also be present, which is low or low-normal heart rate despite the presence of a fever.[18]

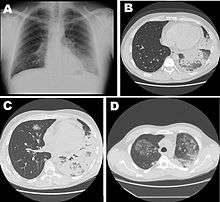

Laboratory tests may show that kidney functions, liver functions and electrolyte levels are abnormal, which may include low sodium in the blood. Chest X-rays often show pneumonia with consolidation in the bottom portion of both lungs. It is difficult to distinguish Legionnaires' disease from other types of pneumonia by symptoms or radiologic findings alone; other tests are required for definitive diagnosis.

Persons with Pontiac fever experience fever and muscle aches without pneumonia. They generally recover in two to five days without treatment. For Pontiac fever the time between exposure and symptoms is generally a few hours to two days.

Cause

Over 90% of cases of Legionnaires' disease are caused by the bacteria Legionella pneumophila. Other types include L. longbeachae, L. feeleii, L. micdadei, and L. anisa.

Transmission

Legionnaires' disease is usually spread by the breathing in of aerosolized water and/or soil contaminated with the Legionella bacteria.[16] Experts have stated that Legionnaires' disease is not transmitted from person to person.[19] In 2014 there was one case of possible spread from someone sick to the caregiver.[20] Rarely, it has been transmitted by direct contact between contaminated water and surgical wounds.[16] The bacteria grows best at warm temperatures.[5] It thrives at water temperatures between 25 and 45 °C (77 and 113 °F), with an optimum temperature of 35 °C (95 °F).[21] Temperatures above 60 °C (140 °F) kill it.[22] Sources where temperatures allow the bacteria to thrive include hot water tanks, cooling towers, and evaporative condensers of large air conditioning systems, such as those commonly found in hotels and large office buildings. Though the first known outbreak was in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, cases of legionellosis have occurred throughout the world.[15]

Reservoirs

L. pneumophila thrives in aquatic systems where it is established within amoebae in a symbiotic relationship.[23] In the built environment, central air conditioning systems in office buildings, hotels, and hospitals are sources of contaminated water.[21] Other places it can dwell include cooling towers used in industrial cooling systems, evaporative coolers, nebulizers, humidifiers, whirlpool spas, hot water systems, showers, windshield washers, fountains, room-air humidifiers, ice-making machines, and misting systems typically found in grocery-store produce sections.[16][24]

The disease may also be transmitted from contaminated aerosols generated in hot tubs if the disinfection and maintenance program is not followed rigorously.[25] Freshwater ponds, creeks, and ornamental fountains are potential sources of Legionella.[26] The disease is particularly associated with hotels, fountains, cruise ships, and hospitals with complex potable water systems and cooling systems. Respiratory care devices such as humidifiers and nebulizers used with contaminated tap water may contain Legionella species, so using sterile water is very important.[27] Other sources include exposure to potting mix and compost.[28]

Legionella bacteria survive in water as intracellular parasites of water-dwelling protozoae, such as amoebae. Amoebae are often part of biofilms, and once Legionella and infected amoebae are protected within a biofilm, they are particularly difficult to destroy.[16]

Mechanism

Legionella enters the lung either by aspiration of contaminated water or inhalation of aerosolized contaminated water or soil. In the lung, the bacteria are consumed by macrophages, a type of white blood cell, inside of which the Legionella bacteria multiply causing the death of the macrophage. Once the macrophage dies, the bacteria are released from the dead cell to infect other macrophages. Virulent strains of Legionella kill macrophages by blocking the fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes inside the host cell; normally the bacteria are contained inside the phagosome, which merges with a lysosome, allowing enzymes and other chemicals to break down the invading bacteria.[15]

Diagnosis

People of any age may suffer from Legionnaires' disease, but the illness most often affects middle-aged and older persons, particularly those who smoke cigarettes or have chronic lung disease. Immunocompromised people are also at higher risk. Pontiac fever most commonly occurs in persons who are otherwise healthy.

The most useful diagnostic tests detect the bacteria in coughed up mucus, find Legionella antigens in urine samples, or allow comparison of Legionella antibody levels in two blood samples taken 3 to 6 weeks apart. A urine antigen test is simple, quick, and very reliable, but it will only detect Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1, which accounts for 70 percent of disease caused by L. pneumophila, which means use of the urine antigen test alone may miss as many as 40% of cases.[21] This test was developed by Richard Kohler in 1982.[29] When dealing with Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1, the urine antigen test is useful for early detection of Legionnaire's disease and initiation of treatment, and has been helpful in early detection of outbreaks. However, it will not identify the specific subtypes, so it cannot be used to match the person with the environmental source of infection. The Legionella bacteria can be cultured from sputum or other respiratory samples. Legionella stains poorly with Gram stain, stains positive with silver, and is cultured on charcoal yeast extract with iron and cysteine (CYE agar).

A significant under-reporting problem occurs with legionellosis. Even in countries with effective health services and readily available diagnostic testing, about 90 percent of cases of Legionnaires' disease are missed. This is partly due to Legionnaires' disease being a relatively rare form of pneumonia, which many clinicians may not have encountered before and thus may misdiagnose. A further issue is that people with legionellosis can present with a wide range of symptoms, some of which (such as diarrhea) may distract clinicians from making a correct diagnosis.[30]

Prevention

Although the risk of Legionnaires' disease being spread by large-scale water systems cannot be eliminated, it can be greatly reduced by writing and enforcing a highly detailed, systematic water safety plan appropriate for the specific type of facility involved (office building, hospital, hotel, spa, cruise ship, etc.)[15] Some of the elements that such a plan may include are the following:

- Keeping water temperature either above or below the 20–50 °C (68–122 °F) range in which the Legionella bacterium thrives.

- Preventing stagnation, for example by removing from a network of pipes any sections that have no outlet (dead ends). Where stagnation is unavoidable, for example when a wing of a hotel is closed for the off-season, systems must be thoroughly disinfected just prior to resuming normal operation.

- Preventing the buildup of biofilm, for example by not using (or by replacing) construction materials that encourage its development, and by reducing the quantity of nutrients for bacterial growth that enter the system.

- Periodic disinfection of the system, by high heat or a chemical biocide, and the use of chlorination where appropriate.

- System design (or renovation) that reduces the production of aerosols and reduces human exposure to them, for example by directing them well away from building air intakes.

An effective water safety plan will also cover such matters as training, record-keeping, communication among staff, contingency plans and management responsibilities. The format and content of the plan may be prescribed by public health laws or regulations.[15]

Treatment

Effective antibiotics include most macrolides, tetracyclines, ketolides, and quinolones.[16] Legionella multiply within the cell, so any effective treatment must have excellent intracellular penetration. Current treatments of choice are the respiratory tract quinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin) or newer macrolides (azithromycin, clarithromycin, roxithromycin). The antibiotics used most frequently have been levofloxacin, doxycycline, and azithromycin.

Macrolides (azithromycin) are used in all age groups, while tetracyclines (doxycycline) are prescribed for children above the age of 12 and quinolones (levofloxacin) above the age of 18. Rifampicin can be used in combination with a quinolone or macrolide. It is uncertain whether rifampicin is an effective antibiotic to take for treatment. The Infectious Diseases Society of America does not recommend the use of rifampicin with added regimens. Tetracyclines and erythromycin led to improved outcomes compared to other antibiotics in the original American Legion outbreak. These antibiotics are effective because they have excellent intracellular penetration in Legionella-infected cells. The recommended treatment is 5–10 days of levofloxacin or 3–5 days of azithromycin, but in people who are immunocompromised, have severe disease, or other pre-existing health conditions, longer antibiotic use may be necessary.[16] During outbreaks, prophylactic antibiotics have been successfully used to prevent Legionnaires' disease in high-risk individuals who have possibly been exposed.[16]

The mortality at the original American Legion convention in 1976 was high (34 deaths in 180 infected individuals) because the antibiotics used (including penicillins, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides) had poor intracellular penetration. Mortality has plunged to less than 5% if therapy is started quickly. Delay in giving the appropriate antibiotic leads to higher mortality.

Prognosis

The fatality rate of Legionnaires' disease has ranged from 5% to 30% during various outbreaks and approaches 50% for nosocomial infections, especially when treatment with antibiotics is delayed.[31] Hospital-acquired Legionella pneumonia has a fatality rate of 28%, and the principal source of infection in such cases is the drinking-water distribution system.[32]

Epidemiology

Legionnaires' disease acquired its name in July 1976, when an outbreak of pneumonia occurred among people attending a convention of the American Legion at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia. Of the 182 reported cases, mostly men, 29 died.[33] On January 18, 1977, the causative agent was identified as a previously unknown strain of bacteria, subsequently named Legionella, and the species that caused the outbreak was named Legionella pneumophila.[34][35]

Outbreaks of Legionnaires' disease receive significant media attention. However, this disease usually occurs in single, isolated cases not associated with any recognized outbreak. When outbreaks do occur, they are usually in the summer and early autumn, though cases may occur at any time of year. Most infections occur in those who are middle-aged or older.[31] National surveillance systems and research studies were established early, and in recent years improved ascertainment and changes in clinical methods of diagnosis have contributed to an upsurge in reported cases in many countries. Environmental studies continue to identify novel sources of infection, leading to regular revisions of guidelines and regulations. About 8,000 to 18,000 cases of Legionnaires' disease occur each year in the United States, according to the Bureau of Communicable Disease Control.[36]

Between 1995 and 2005, over 32,000 cases of Legionnaires' disease and more than 600 outbreaks were reported to the European Working Group for Legionella Infections The data on Legionella are limited in developing countries and Legionella-related illnesses likely are underdiagnosed worldwide.[15] Improvements in diagnosis and surveillance in developing countries would be expected to reveal far higher levels of morbidity and mortality than are currently recognised. Similarly, improved diagnosis of human illness related to Legionella species and serogroups other than Legionella pneumophila would improve knowledge about their incidence and spread.

A 2011 study successfully used modeling to predict the likely number of cases during Legionnaires’ outbreaks based on symptom onset dates from past outbreaks. In this way, the eventual likely size of an outbreak can be predicted, enabling efficient and effective use of public health resources in managing an outbreak.[37]

History

The first recognized cases of Legionnaires' disease occurred in 1976 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Among more than 2000 attendees of an American Legion convention held at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, 221 attendees contracted the disease and 34 of them died.[38]

In April 1985, 175 people in Stafford, England, were admitted to the District or Kingsmead Stafford Hospitals with chest infection or pneumonia. A total of 28 people died. Medical diagnosis showed that Legionnaires' disease was responsible and the immediate epidemiological investigation traced the source of the infection to the air-conditioning cooling tower on the roof of Stafford District Hospital.

In March 1999, a large outbreak in the Netherlands occurred during the Westfriese Flora flower exhibition in Bovenkarspel; 318 people became ill and at least 32 people died. This was the second-deadliest outbreak since the 1976 outbreak and possibly the deadliest as several people were buried before Legionnaires' disease had been diagnosed.

The world's largest outbreak of Legionnaires' disease happened in July 2001 with people appearing at the hospital on July 7, in Murcia, Spain. More than 800 suspected cases were recorded by the time the last case was treated on July 22; 636–696 of these cases were estimated and 449 confirmed (so, at least 16,000 people were exposed to the bacterium) and six died, a case-fatality rate around 1%.

In late September 2005, 127 residents of a nursing home in Canada became ill with L. pneumophila. Within a week, 21 of the residents had died. Culture results at first were negative, which is not unusual, as L. pneumophila is a fastidious bacterium, meaning it requires specific nutrients and/or living conditions in order to grow. The source of the outbreak was traced to the air-conditioning cooling towers on the nursing home's roof.

As of 12 November 2014, 302 people have been hospitalized following an outbreak of Legionella in Portugal and 7 related deaths have been reported. All cases, so far, have emerged in three civil parishes from the municipality of Vila Franca de Xira in the northern outskirts of Lisbon, Portugal and are being treated in hospitals of the Greater Lisbon area. The source is suspected to be located in the cooling towers of the fertilizer plant Fertibéria.[39]

Twelve people were diagnosed with the disease in the Bronx, New York, in December 2014; the source was traced to contaminated cooling towers at a housing development.[40] In July and August 2015, another, unrelated outbreak in the Bronx killed 12 people and made about 120 people sick; the cases arose from a cooling tower on top of a hotel. At the end of September another person died of the disease and 13 were sickened in yet another unrelated outbreak in the Bronx.[41] The cooling towers from which the people were infected in the latter outbreak had been cleaned during the summer outbreak, raising concerns about how well the bacteria could be controlled.[42]

On August 28, 2015, an outbreak of Legionnaire's disease was detected at San Quentin State Prison in Northern California.[43]

Between June 2015 and January 2016, 87 cases of Legionnaires' disease were reported by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services for the city of Flint, Michigan and surrounding areas. 10 of those cases were fatal.[44]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Cunha, BA; Burillo, A; Bouza, E (23 January 2016). "Legionnaires' disease.". Lancet (London, England). 387 (10016): 376–85. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60078-2. PMID 26231463.

- ↑ Mahon, Connie (2014). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 416. ISBN 9780323292610.

- ↑ "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) About the Disease". CDC. January 26, 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) Signs and Symptoms". CDC. January 26, 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) Causes and Transmission". CDC. March 9, 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) People at Risk". CDC. January 26, 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) Clinical Features". CDC. October 28, 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) Diagnostic Testing". CDC. November 3, 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) Prevention". CDC. January 26, 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) Treatment and Complications". CDC. January 26, 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ Mandell, LA; Wunderink, RG; Anzueto, A; Bartlett, JG; Campbell, GD; Dean, NC; Dowell, SF; File TM, Jr; Musher, DM; Niederman, MS; Torres, A; Whitney, CG; Infectious Diseases Society of, America; American Thoracic, Society (1 March 2007). "Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults.". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 Suppl 2: S27–72. doi:10.1086/511159. PMID 17278083.

- 1 2 "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) History and Disease Patterns". CDC. January 22, 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever) Prevention". CDC. October 28, 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever)". CDC. January 15, 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Legionella and the prevention of legionellosis (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2007. ISBN 9241562978.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cunha, Burke A; Burillo, Almudena; Bouza, Emilio (2015). "Legionnaires' disease". The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60078-2. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ Edelstein PH. Legionnaires Disease: History and clinical findings. Open Access Biology http://www.open-access-biology.com/legionella/edelstein.html

- ↑ Ostergaard L, Huniche B, Andersen PL (November 1996). "Relative bradycardia in infectious diseases". J. Infect. 33 (3): 185–91. doi:10.1016/S0163-4453(96)92225-2. PMID 8945708.

- ↑ "Legionella (Legionnaires' Disease and Pontiac Fever)". CDC. January 22, 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ "Probable Person-to-Person Transmission of Legionnaires' Disease". NEJM. January 23, 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 Fields, B. S.; Benson, R. F.; Besser, R. E. (2002). "Legionella and Legionnaires' Disease: 25 Years of Investigation". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 15 (3): 506–526. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.3.506-526.2002. ISSN 0893-8512.

- ↑ "HSE - Legionnaires' disease - Hot and cold water systems - Things to consider".

- ↑ Winiecka-Krusnell J, Linder E (1999). "Free-living amoebae protecting Legionella in water: The tip of an iceberg?". Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 31 (4): 383–385. doi:10.1080/00365549950163833. PMID 10528878.

- ↑ Mahoney FJ, Hoge CW, Farley TA, Barbaree JM, Breiman RF, Benson RF, McFarland LM (1 April 1992). "Communitywide Outbreak of Legionnaires' Disease Associated with a Grocery Store Mist Machine". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 165 (4): 736–739. doi:10.1093/infdis/165.4.xxxx. PMID 1552203.

- ↑ Silivanch v. Celebrity Cruises, Inc., 171 F.Supp.2d 241 (S.D.N.Y. 2001) (plaintiff successfully sued cruise line and manufacturer of filter after catching disease on cruise)

- ↑ Winn WC Jr (1996). "Legionella". In Baron S; et al. Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. Via NCBI Bookshelf.

- ↑ Woo AH, Goetz A, Yu VL (November 1992). "Transmission of Legionella by respiratory equipment and aerosol generating devices". Chest. 102 (5): 1586–90. doi:10.1378/chest.102.5.1586. PMID 1424896.

- ↑ Cameron S, Roder D, Walker C, Feldheim J (1991). "Epidemiological characteristics of Legionella infection in South Australia: implications for disease control". Aust N Z J Med. 21 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.1991.tb03007.x. PMID 2036080.

- ↑ Kohler R, Wheat LJ (September 1982). "Rapid diagnosis of pneumonia due to Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1". J. Infect. Dis. 146 (3): 444. doi:10.1093/infdis/146.3.444. PMID 7050258.

- ↑ Makin, T (January 2008). "Legionella bacteria and solar pre-heating of water for domestic purposes" (PDF). UK Water Regulations Advisory Scheme Report: 4.

- 1 2 "Legionnaire disease". Medline Plus. US National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Stout JE, Muder RR, Mietzner S, Wagener MM, Perri MB, DeRoos K, Goodrich D, Arnold W, Williamson T, Ruark O, Treadway C, Eckstein EC, Marshall D, Rafferty ME, Sarro K, Page J, Jenkins R, Oda G, Shimoda KJ, Zervos MJ, Bittner M, Camhi SL, Panwalker AP, Donskey CJ, Nguyen MH, Holodniy M, Yu VL (July 2007). "Role of environmental surveillance in determining the risk of hospital-acquired legionellosis: a national surveillance study with clinical correlations". Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 28 (7): 818–24. doi:10.1086/518754. PMID 17564984. as PDF

- ↑ "Legionnaire disease". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ↑ McDade JE, Brenner DJ, Bozeman FM (1979). "Legionnaires' disease bacterium isolated in 1947". Ann. Intern. Med. 90 (4): 659–61. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-90-4-659. PMID 373548.

- ↑ Fraser DW, Tsai TR, Orenstein W, Parkin WE, Beecham HJ, Sharrar RG, Harris J, Mallison GF, Martin SM, McDade JE, Shepard CC, Brachman PS (1977). "Legionnaires' disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia". N. Engl. J. Med. 297 (22): 1189–97. doi:10.1056/NEJM197712012972201. PMID 335244.

- ↑ "Legionellosis.". Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Bureau of Communicable Disease Control. Nov 2011. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- ↑ Egan JR, Hall IM, Lemon DJ, Leach S (March 2011). "Modeling Legionnaires' disease outbreaks: estimating the timing of an aerosolized release using symptom-onset dates.". Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.). 22 (2): 188–98. doi:10.1097/ede.0b013e31820937c6. PMID 21242803.

- ↑ In Philadelphia 30 Years Ago, an Eruption of Illness and Fear, Lawrence K. Altman, The New York Times, August 1, 2006

- ↑ Arreigoso, Vera Lúcia. "Surto de legionella é o terceiro maior de sempre no mundo: 302 infetados e sete mortos". Jornal Expresso. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ Reuters Editorial (29 July 2015). "Legionnaires' disease kills two, sickens 31 in New York City". Reuters. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "One Dead in New Bronx Outbreak of Legionnaires' Disease". The New York Times. 1 October 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/02/nyregion/legionnaires-bacteria-regrew-in-bronx-cooling-towers-that-were-disinfected.html Legionnaires’ Bacteria Regrew in Bronx Cooling Towers That Were Disinfected

- ↑ "Legionnaires Disease Confirmed at San Quentin Prison". Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Sarah Kaplan (14 January 2016). "Flint, Mich., has 10 fatal cases of Legionnaires' disease; unclear if linked to water". Washington Post. Retrieved 31 March 2016.