List of rulers of Odisha

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Odisha |

|---|

| History |

| Culture |

|

|

|

The land of Odisha has undergone several changes in terms of its boundaries since ancient ages. It was also known by different names like Kalinga, South Kosala or Utkala in different eras. The year 1568 is considered a turning point in the history of Odisha. In the year 1568, Kalapahad invaded the state. This, aided by internal conflicts, led to a steady downfall of the state from which it didn't recover.

Ancient Period

Ancient Texts

According to Mahabharata and some Puranas, the prince Kalinga founded the kingdom of Kalinga, in the current day region of coastal Odisha, including the North Sircars.[1] The Mahabharata also mentions one Srutayudha as the king of the Kalinga kingdom, who joined the Kaurava camp.[2] In the Buddhist text, Mahagovinda Suttanta, Kalinga and its ruler, Sattabhu, have been mentioned.[3]

- Kalinga (?)

- Srutayudha (?)

- Sattabhu (8th Century B.C.)

- Nalikira (8th Century B.C)

- Karakandu (7th Century B.C)

Unknown Dynasty Mentioned in Chullakalinga Jataka and Kalingabodhi Jataka

- Kalinga I

- Mahakalinga

- Chulakalinga

- Kalinga II (7th – 6th Century B.C)

Unknown Dynasty Mentioned in Dathavamsha

- Brhamadatta (5th Century B.C)

- Kasiraja

- Sunanda

Ruler Mentioned in Dathavamsha

- Guhasiva (4th Century B.C)

Nanda Dynasty

Kalinga was annexed by Mahapadma Nanda.

- Mahapadma Nanda (c. 424 BCE – ?)

- Pandhuka

- Panghupati

- Bhutapala

- Rashtrapala

- Govishanaka

- Dashasidkhaka

- Kaivarta

- Mahendra

- Dhana Nanda (Argames) (? – c. 321 BCE)

When Chandragupta I rebelled against the Nandas, Kaligans broke away from the empire of Magadha.

Maurya Empire

Ashoka invaded Kalinga in 261 BCE. Kalinga broke away from the Mauryan empire during the rule of Dasharatha.

- Ashoka (274-232 BCE)

- Dasharatha (232–224 BCE)

Mahameghavahana Dynasty

Mahamegha Vahana was the founder of the Kalingan Chedi or Cheti Dynasty.[4][5] But, Kharavela is the most well-known among them. The exact relation between Mahamegha Vahana and Kharavela is not known.[4]

- Mahamegha Vahana (?)

- Kharavela (c.193 BCE-?)

- Kudepasiri (?)

- Vakadeva (or Vakradeva) (?)

It is not known that, if Vakadeva was a successor or predecessor of Kharavela.[6] From the inscriptions and coins discovered at Guntupalli and Velpuru, Andhra Pradesh, we know of a series of rulers with the suffix Sada who were possibly distant successors of Kharavela.[7]

- Mana-Sada

- Siri-Sada

- Maha-Sada

- Sivamaka-Sada

- Asaka-Sada

Satavahana Dynasty

Gautamiputra Satakarni is known to have invaded Kalinga during his reign.[8]

- Gautamiputra Satkarni (78–102 CE)

- Sri Yajna Satkarni (170–199 CE)

The history of the region is obscure for a while after the reign of Sri Yajna Satkarni.[8]

Kusanas and Murundas

Only numismatic evidences have been found of some of these rulers of 3rd century CE.

Naga Dynasty

An inscription dating from 3rd to 4th century found in Asanpat village in Keonjhar revealed the existence of this dynasty.[10]

- Manabhanja (?)

- Satrubhanja (?)

- Disabhanja (?)

Nala Dynasty

For some time in 4th century, the region around modern-day Koraput was ruled by the Nalas.[8][11]

- Vrishadhvaja (c. 400-420 CE)

- Varaharaja (c. 420-440 CE)

- Bhavadattavarman or Bhavadattaraja (?)

- Arthapatiraja (?)

- Skandavarman (c. 480-?)

Parvatadvarka Dynasty

During the same period as the Nalas, the region around modern-day Kalahandi was ruled by them. Not much is known about them.[8]

- Sobhanaraja (?)

- Tustikara (?)

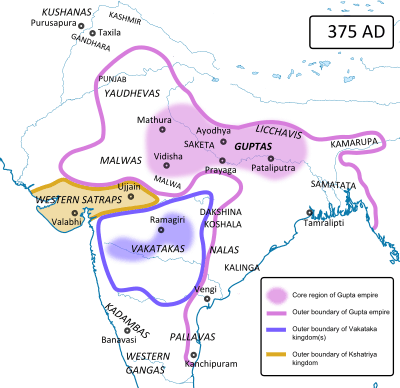

Gupta Empire

Samudragupta invaded Kalinga during his reign in c.350.[8] By c.571, most of Kalinga had broken away from the Gupta empire.[12]

- Samudragupta (335–375 CE)

- Ramagupta (?)

- Chandragupta II (375–415 CE)

- Kumaragupta I (414–455 CE)

- Skandagupta (455–467 CE)

- Purugupta (467–473 CE)

- Kumaragupta II (473–476)

- Budhagupta (476–495?)

- Kumaragupta III (?)

- Vishnugupta (?)

- Vainyagupta (?)

- Bhanugupta (540 to 550 CE)

Sura Dynasty

The later half of the 4th century, this dynasty was established in the South Kosala region.[8][13]

- Maharaja Sura

- Maharaja Dayita I (or Dayitavarman I)

- Maharaja Bhimasena I

- Maharaja Dayitavarman II

- Maharaja Bhimasena II (c. 501 or 601-?)

Sarabhapuriya Dynasty

Not much is known about this dynasty. Everything known about them, comes from the inscriptions on copper plates and coins. They may or may not have also been known as the Amararyakula dynasty.[14] This dynasty is supposed to have started by one Sarabha, who may have been a feudal chief under the Guptas. They ruled over the modern-day region of Raipur, Bilaspur and Kalahandi.[14]

- Sarabha (c. 499?-?)

- Narendra (c. 525?-?)

- Mahendraditya

- Prasannamatra

- Jayaraja (c. 550-560?)

- Manamatra (c. 560-570?)

- Sudevaraja I(c. 571-580?)

- Pravaraja (c. 590-?)

- Vyaghraraja

- Durgaraja

- Suravala

- Sudevaraja II (c. 700-?)

Mathara Dynasty

The Mathara dynasty ruled during the 4th and the 5th centuries. The Mathara rulers include:[15]

- Shakti-varman (Śaktivarman)

- Prabhanjana-varman (Prabhañjanavarman)

- Ananta-shakti-varman (Anantaśaktivarman)

Vishnukudina Empire

Anantasaktivarman lost southern part of his kingdom to Madhava Verma I and the Matharas never recovered it.[8]

- Madhava Varma I (420-55 CE)

- Indra Varma (?)

- Madhava Verma II (461-508 CE)

- Vikramendra Varma I

- Indra Bhattaraka Varma (528–555 CE)

Indra Bhattaraka Varma possibly lost his Kalinga holdings to one Adiraja Indra, who possibly was Indravarma I of East Ganga Dynasty.[8][16]

Vigraha Dynasty

They ruled the region called South Tosali, around modern day Puri and Ganjam, during second half of 6th century.[11]

- Prighivi Vigraha

- Loka Vigraha (c. 600 CE-?)

Mudgalas Dynasty

They ruled the region of North Toshali, the river Mahanadi served as the border between North and South Toshali. In 603 CE, they captured South Toshali from the Vigrahas.[11]

- Sambhuyasa (c. 580? CE-?)[12]

Durjaya Dynasty

In mid-6th century CE, a chief, Ranadurjaya, established himself in South Kalinga.[17] Prithivimaharaja probably defeated the Mudgalas by his time.[8][17]

- Ranadurjaya (?)

- Prithivimaharaja (?)

Gauda Empire

Shashanka invaded and possibly occupied northern parts of Kalinga during his reign around c. 615.[8][12]

Shailobhava Dynasty

They ruled from the region ranging from coastal Orissa to Mahanadi and to Mahendragiri in Paralakhemundi. This region was called the Kangoda mandala.[11] Sailobhava, the founder of dynasty, is said to have born of a rock, hence the name Sailobhava.[18] Sailobhava was the adopted son of one Pulindasena, who was possibly a chieftain. They were possibly the subordinates of Shashanka during Madhavaraja II, then they later rebelled.[8][19]

- Pulindasena (?)

- Sailobhava (?)

- Dharmaraja I (or Ranabhita)

- Madhavaraja I (or Sainyabita I)

- Ayasobhita I (or Chharamparaja)

- Madhavaraja II (or Madhavavarman) (?-665 CE)

- Madhyamaraja I (or Ayasobhita II) (665 CE-?)

- Dharmaraja II

Harsha

Harsha invaded Kalinga and Kangoda, soon after the death Pulakesi II in 642 CE. Madhavaraja II was the vassal of Harsha until the death of later in 647 CE.[8]

- Harsha (606-647)

Bhaumakara Dynasty

The Bhauma or Bhauma-Kara Dynasty lasted from c.736 CE to c.940 CE.[20] They mostly controlled the coastal areas of Kalinga. But by c.850 CE, they controlled most of modern Orissa. The later part of their reign was disturbed by rebellions from the Bhanja dynasty of the Sonepur and Boudh region.[21]

- Lakshmikaradeva (?)

- Ksemankaradeva (?)

- Sivakaradeva I (or Unmattasimha) (c.736-?)

- Subhakaradeva I (c.790-?)

- Sivakaradeva II (c.809-?)

- Santikaradeva I (or Gayada I) (?)

- Subhakaradeva II (c.836-?)

- Subhakaradeva III (?-845)

- Tribhuvana Mahadevi (widow of Santikaradeva I) (c.845-?)

- Santikaradeva II (?)

- Subhakaradeva IV (or Kusumahara II) (c.881-?)

- Sivakaradeva III (or Lalitahara) (c.885-?)

- Tribhuvana Mahadevi II (or Prithivi Mahadevi, window of Subhakara IV) (c.894-?)

- Tribhuvana Mahadevi III (widow of Sivakara III) ?

- Santikaradeva III (?)

- Subhakara V (?)

- Gauri Mahadevi (wife of Subhakara) (?)

- Dandi Mahadevi (daughter of Gauri) (c.916 or 923-?)

- Vakula Mahadevi (stepmother of Dandi Mahadevi) (?)

- Dharma Mahadevi (widow of Santikaradeva) (?)

The Mandala States

Between the 8th and 11th century, Orissa was divided into mandalas which were feudal states ruled by chieftains.[11] These chieftains swore allegiance to the Bhaumakaras.

Bhanjas of Khinjali Mandala

Khinjali refers to modern-day Balangir, Sonepur and Phulbani.

- Silabhanja Deva (or Angadi) (?)

- Satrubhanja (or Gandhata and Nettabhanja I) (?)

- Rangabhanja (?)

- Nettabhanja II (or Kalyankalasa) (?)

- Silabhanja II (or Tribhuvana Kalasa) (?)

- Vidhyadharabhanja (or Amogha Kalasa and Dharma Kalasa) (?)

- Nettabhanja III (or Kalyan Kalasa and Prithvi Kalasa) (c. 933 CE-?)

- Satrubhanja II (or Tribhubana Kalasa) (c. 934-?)

- Bettabhanja IV (or Tribhuvana Kalasa) (c. 949-?)

Bhanjas of Khijjinga Mandala

This refers to modern-day Mayurbhanj and part of Kendujhar

- Kottabhanja

- Digbhanja (alias Durjayabhanja)

- Ranabhanja (c.924-?)

- Prithvibhanja (alias Satrubhanja) (c. 936-?)

- Rajabhanja (alias Rajabhanja)

Sulkis of Kodalaka Mandala

Kodalaka refers to the modern-day district of Dhenkanal.

- Kanchanastambha who was succeeded by his son Kalahastambha.

- Ranastambha (c.839-?)

- Jayasthambha

- Kulastambha II

Later, the mandala was divided into two parts, Yamagartta Mandala and Airavatta Mandala. The Bhaumas allowed the Tunga and the Nandodbhava families to rule over Yamagartta Mandala and Airavatta Mandala respectively.

Tungas of Yamagartta Mandala

The Mandala refers to the northern part of modern Dhenkanal district. Jayasimha was ruler of the mandala before the Tungas, he was not a member of the Tunga dynasty.

- Jayasimha (c. 864 )

- Khadaga Tunga

- Vinita Tunga

- Solana Tunga

- Gayada Tunga

- Apsara Deva.

It is not clearly known if Apsara Deva belonged to the Tunga family or not.

Nandodbhavas of Airavatta Mandala

This region extended over the territory comprising southern part of Dhenkanal district, some western portion of Cuttack district and almost the entire Nayagarh district.

- Jayananda

- Paramananda

- Sivananda

- Devananda I

- Devananda II (c. 920-?)

- Dhruvananda (c. 929-?)

Mayuras of Banei Mandala

This region roughly comprised the modern-day Banei sub-division and parts of Panposh subdivision of Sundergarh district.

- Udita Varsha

- Teja Varsha

- Udaya Varsha

Gangas of Svetaka Mandala

The capital of Svetaka known as Svetakapura has been identified with modern Chikiti.

- Jayavarma Deva

- Anantavarman

- Gangaka Vilasa

- Bhupendra Varman

- Mahendravarman

- Prithivarman

- Indravarman I

- Indravarman II

- Samantavarman (c. 909-921?)

Somavamsi Dynasty

The Soma or Kesari Dynasty originates in South Kosala, but by the reign of Yayati I, they controlled most of modern Orissa.[22]

- Janmejaya I (c. 882-992)[23]

- Yayati I (c. 922-955)[23]

- Bhimaratha (c. 955-80)

- Dharmarstha (c. 980-1005)

- Nahusa (c. 1005-1021)

- Indranatha (c. 1021-1025)

- Yayati II (c. 1025-1040)

- Udyotakesari (c. 1040-1065)

- Janmejaya II (c. 1065-1080)

- Puranjaya (c. 1080-1090)

- Karnadeva (c. 1090-1110)

Janmejaya, the predecessor of Karnadeva and the son of Janmejaya II,[11] was not considered a ruler by his successors, as he captured the throne in a violent coup and soon-after lost it.[23]

Eastern Ganga Dynasty

Indravarman I is earliest known king of the dynasty. He is known from the Jirjingi copper plate grant.[8][16]

- Indravarman I (c. ?-537?)[8]

- Samantavarman (c. 537-562)

- Hastivarman (c. 562-578)

- Indravarman II (c. 578-589)

- Danarnava (c. 589-652)

- Indravarman III (c. 589-652)

- Gunarnava (c. 652-682)

- Devendravarman I (c. 652-682?)

- Anantavarman III (c. 808-812?)

- Rajendravarman II (c. 812-840?)

- Devendravarman V (c. 885-895?)

- Gunamaharnava I (c. 895-939?)

- Vajrahasta II (or Anangabhimadeva I) (c. 895-939?)

- Gundama - (c. 939-942)

- Kamarnava I (c. 942-977)

- Vinayaditya (c. 977-980)

- Vajrahasta IV (c .980-1015)

- Kamarnava II (c. 1015–6 months after)

- Gundama II (c. 1015-1038)

- Vajrahasta V (c. 1038-1070)

- Rajaraja I (c. 1070-1077)

- Anantavarman Chodaganga (c. 1077–1147)

- Jatesvaradeva (c. 1147–1156)

- Raghavadeva (c. 1156-1170)

- Rajaraja III (c. 1170-1190)

- Anangabhimadeva II (c. 1190–1198)

- Rajradeva III (c. 1198-1211)

- Anangabhimadeva III (c. 1211-1238)

- Narasimhadeva I (1238–1264)

- Bhanudeva I (1264–1278)

- Narasimhadeva II (1279–1306)

- Bhanudeva II (1306–1328)

- Narasimhadeva III (1328–1352)

- Bhanudeva III (1352–1378)

- Narasimhadeva IV (1378–1414)

- Bhanudeva IV (1414–1434)

Medieval Period

Gajapati Dynasty

- Kapilendra Deva (1434–67)

- Purushottama Deva (1467–97)

- Prataparudra Deva (1497–1534)

- Kaluadeva (alias Ramachandradeva)

- Kakharuadeva (alias Purushottamdeva)

Govinda Vidyadhara, the general of Prataparudra, killed Prataparudra's remaining sons in c.1541 and began the Bhoi Dynasty.[24][23]

Bhoi Dynasty

- Govinda Vidyadhara (1541–48)[25]

- Raghubhanja Chhotray (nephew of Govinda Vidyadhara)

- Chakrapratap (1548–57)[26]

- Narasimha Jena

- Raghuram Jena

Bhoi dynasty was short lived but during their reign Orissa came into conflicts with the invaders from Golconda.

Mukunda Deva

Mukunda Deva come to throne by a bloody coup but his reign was cut short by the armies of Sulaiman Khan Karrani which were led by Kalapahad. Ramachandra Bhanja, a feudal lord of Sarangagarh of Kandhamal, took the opportunity to rebel.

- Mukunda Deva (1559–68)[24]

- Ramachandra Bhanja (1568)

Karranis of Bengal

Instigated by Mukunda Deva's alliance with Akbar, Sulaiman's army led by Kalapahad and Bayazid invaded Orissa in 1568.

- Sulaiman Khan Karrani (1566–1572)

- Bayazid Khan Karrani (1572)

- Daud Khan Karrani (1572–12 July 1576)

In the Battle of Tukaroi, which took place in modern-day Balasore, Daud was defeated and retreated deep into Orissa. The battle led to the Treaty of Katak in which Daud ceded the whole of Bengal and Bihar, retaining only Orissa.[27] The treaty eventually failed after the death of Munim Khan (governor of Bengal and Bihar) who died at the age of 80. Sultan Daud Khan took the opportunity and invaded Bengal. This would lead to the Battle of Raj Mahal in 1576.[27][28]

Mughal Empire

- Qutlu Khan Lohani (former officer of Daud, ruler of North Orissa and south Bengal) (1590)[18]

- Nasir Khan (son of Qutlu Khan, Mughal vassal) (1590-1592)

- Man Singh I (Mughal Subahdar) (1592-1606)

Man Singh I attacked Nasir Khan when the later broke a treaty by attacking the temple town of Puri. Orissa was annexed into the Bengal subah (province).

The Mughal rule was weak in the region, this allowed local chieftains to somewhat enjoy a semi-independence.

Subahdars of Orissa

Under Jahagir, Orissa was made into a separate subah.[29]

- Quasim Khan (Mughal Subahdar) (1606-?)[30]

- Kalyan Mal (Mughal Subahdar, son of Todar Mal) (c. 1610-1617)[29][30][31]

- Mukarram Khan (1617-1620)[30]

- Ahmad Beg (1620-1628)

- Baqar Khan (1628-1632)

- Shah Shuja(son of Shah Jahan, Subahdar of Bengal) (1639-1660)[30]

- Zaman Teharani (deputy of Shah Shuja) (1642-1646)

- Mutaqad Khan Mirza Makki (deputy of Shah Shuja) (1646-1648)

- Mirza Jan Beg (deputy of Shah Shuja) (1648-1651)

- Khan-i-Duran (Subahdar under Aurangzeb) (1660-1667)

- Murshid Quli Khan (initially Subahdar of Orissa, later Nawab of Bengal) (1714–1727)

- Shuja-ud-Din (initially Subahdar of Orissa, later Nawab of Bengal) (1719–1739)

- Taqi Khan (deputy of Shuja-ud-Din) (1727-1734)

- Murshid Quli Khan II (deputy of Shuja-ud-Din) (1734-1741)

- Sarfaraz Khan (Nawab of Bengal) (1727 and 1739–1740)

- Alivardi Khan (Nawab of Bengal, acquired Orissa in 1741) (1740–1756)

The later part of the Mughal empire was frequently marred with rebellions from local chieftains. The neighbouring subahs also encroached areas from Orissa.[8]

Rajas of Khurda

After 1592, the centre of power had shift from Katak to Khurda. During the reign of Purusottam Deva, relations with the Mughal Subahdars soured.[29]

- Ramachandra Rath I (Mughal vassal, ruler of Khurda) (?-1607)[29]

- Purusottam Rath (ruler of Khurda) (1607-1622)

- Narasimha Rath (ruler of Khurda) (1622-1645)

- Gangadhara Rath (nephew of Narasimha Rath) (1645-murdered in 4 months)

- Balabhadra Rath (brother of Narasimha Rath) (1645-1655)

- Mukunda Rath I (1655-1690)

- Dibysingha Rath I (c. 1700-1720)

- Harekrushna Rath (1720-1725)

- Gopinath (1725-1732)

- Ramachandra Rath II (forcibly converted to Islam,[29] alias Hafiz Qadar Muhammad) (1732-1742/43)[29]

- Bhagirathi Kumar

- Padmanava Rath (1736-1739)

- Birakesari Rath (1739-?)

- Birakishore Rath (Maratha vassal) (c. 1751-1780)

- Dibyasingha Deva II (Maratha vassal) (1780-1795)

- Mukundeva Deva II (Maratha vassal, later ceded to British empire)(1795-)

The Rajas of Khurda continued to rule the region well into the 1800s but by then their power had diminished. Then the Rajas along with other local chieftain led a series of rebellions against the British.

Maratha Empire

Maratha general, Raghoji I Bhonsle signed a treaty with Alivardi Khan, in 1751, ceding the perpetuity of Cuttack up to the river Suvarnarekha to the Marathas.[8]

- Raghoji I Bhonsle (Maratha general of Kanpur) (1751-1755)

Maratha Administrators

- Seo Bhatt Sathe (1751)[32]

- Bhawani Pandit (1764)

- Sambhaji Ganesha (1768)

- Madhaji Hari (1773)

- Rajaram Pandit (1778)

- Sadasiva Rao (1793)

British Colonial Period

Mukundeva Deva II was discontent under Maratha rule, so he agreed to help British troops to march through his territory without resistance.[29] In 1803, Maratha ceded Orissa to the British empire. The Rajas and other local chieftains lead a series of rebellions against the British. Notable among the rebellions is that of Surendra Sai.[8]

Odia speaking people at this time were placed in different provinces. Around 1870, a movement was started to unify the Oriya-speaking within a state. In 1936, the new state of Orissa was formed. About 25 princely states, remained independent but they were later integrated by 1947.

See: List of Governors of Bihar and Orissa

Post Independence

See: List of Governors of Orissa

See: List of Chief Ministers of Orissa

See also

References

- ↑ Gaṅgā Rām Garg (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World, Volume 1. Concept Publishing Company. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa. The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Second Book Sabha Parva. Echo Library. p. 10. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (2006). Political History Of Ancient India. Genesis Publishing. p. 75. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- 1 2 Reddy (2005). General Studies History 4 Upsc. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. A-55. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ↑ Mani, Chandra Mauli (2005). A Journey Through India's Past. Northern Book Centre. p. 51. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (2006). Political History Of Ancient India. Genesis Publishing. p. 348. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ↑ R. T. Vyas; Umakant Premanand Shah (1995). Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects. Abhinav Publications. p. 31. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "Detail History of Orissa". Government of Odisha. Archived from the original on 12 November 2006.

- ↑ Economic History of Orissa. Indus Publishing. p. 28.

- ↑ Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise And Fall Of The Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 60. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 S. C. Bhatt, Gopal K. Bhargava (520). Land and People of Indian States and Union Territories: In 36 Volumes. Orissa, Volume 21. Gyan Publishing House. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha, Cir. 450-1200 A.D. Abhinav Publications. p. 137. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ Deo, Jitāmitra Prasāda Singh (1987). Cultural Profile of South Kōśala. Gyan Books. p. 106.

- 1 2 Ajay Mitra Shastri (1995). Inscriptions of the Sarabhapuriyas Panduvamsins and Somavamsins. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 96, 108, 112.

- ↑ Snigdha Tripathy 1997, p. 8.

- 1 2 Mirashi, Vasudev Vishnu (1975). Literary And Historical Studies In Indology. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 138. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- 1 2 Kapur, Kamlesh (2010). History Of Ancient India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 606. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- 1 2 Shyam Singh Shashi (2000). Encyclopaedia Indica: Minor Dynasties of Ancient Orissa. Anmol Publications. pp. 6, 164.

- ↑ Upinder Singh. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 565. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ Patnaik, Durga Prasad (1989). Palm Leaf Etchings of Orissa. Abhinav Publications. p. 2.

- ↑ Smith, Walter (1994). The Mukteśvara Temple in Bhubaneswar. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 22. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ↑ Smith, Walter (1994). The Mukteśvara Temple in Bhubaneswar. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 24. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Das, Suryanarayan (2010). Lord Jagannath: Through The Ages. Sanbun Publishers. p. 181. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- 1 2 Reddy 2005, p. B-32

- ↑ Bundgaard, Helle (1998). Indian Art Worlds in Contention: Local, Regional and National Discourses on Orissan Patta Paintings. Routledge. p. 72.

- ↑ L.S.S. O'malley (1 January 2007). Bengal District Gazetteer : Puri. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-81-7268-138-8. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- 1 2 The History of India: The Hindú and Mahometan Periods By Mountstuart Elphinstone, Edward Byles Cowell, Published by J. Murray, 1889, [Public Domain]

- ↑ Mountstuart Elphinstone, Edward Byles Cowell (1866). The History of India: The Hindú and Mahometan Periods (Public Domain). Murray.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Rajas of Khurda". Government of Orissa. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Mohammed Yamin (1 July 2009). Impact of Islam on Orissan Culture. Readworthy. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-81-89973-96-4. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ John R. McLane (2002). Land and Local Kingship in Eighteenth-Century Bengal. Cambridge University Press. p. 132. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ Narayan Miśra (1 January 2007). Annals and Antiquities of the Temple of Jagannātha. Sarup & Sons. p. 156. ISBN 978-81-7625-747-3. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

Bibliography

- Snigdha Tripathy (1997). Inscriptions of Orissa. I - Circa 5th-8th centuries A.D. Indian Council of Historical Research and Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1077-8.