Lowndes County, Alabama

| Lowndes County, Alabama | |

|---|---|

Lowndes County Courthouse in Hayneville | |

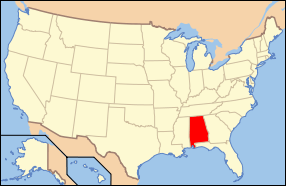

Location in the U.S. state of Alabama | |

Alabama's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | January 20, 1830 |

| Named for | William Lowndes |

| Seat | Hayneville |

| Largest town | Fort Deposit |

| Area | |

| • Total | 725 sq mi (1,878 km2) |

| • Land | 716 sq mi (1,854 km2) |

| • Water | 9.2 sq mi (24 km2), 1.3% |

| Population (est.) | |

| • (2015) | 10,458 |

| • Density | 16/sq mi (6/km²) |

| Congressional district | 7th |

| Time zone | Central: UTC-6/-5 |

|

Footnotes:

| |

Lowndes County is a county of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2010 census, the population was 11,299.[1] Its county seat is Hayneville.[2] The county is named in honor of William Lowndes, a member of the United States Congress from South Carolina.

Lowndes County is part of the Montgomery, Alabama Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Lowndes County was formed from Montgomery, Dallas and Butler counties, by an act of the Alabama General Assembly on January 20, 1830. The county is named for South Carolina statesman William Lowndes.[3]

Following Reconstruction and years in which blacks continued to be elected to local office, the white-Democrat dominated state legislature gained passage of a new constitution in 1901 that effectively disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. Requirements were added for payment of a cumulative poll tax before registering to vote, difficult for poor people to manage; and literacy tests (with a provision for a grandfather clause to exempt illiterate white voters from being excluded.) The number of black voters fell dramatically, as did the number of poor white voters.[4]

From the end of the 19th through the early decades of the 20th centuries, organized white violence increased against blacks, with 14 lynchings recorded in the county, the sixth highest total in the state, which ranks among the most violent in the South. Most victims were black men, subjected to white extra-legal efforts to maintain white supremacy by racial terrorism.[5] Seven of these murders of blacks were committed in Letohatchee; five in 1900 and two in 1917. This is an unincorporated community south of Montgomery. In 1900 mobs killed a black man accused of killing a white man. When local black resident Jim Cross objected, he was killed, too, at his house, followed by his wife, son and daughter. In 1917 two black brothers were killed by a white mob for alleged insolence to a white farmer on the road.[6] On July 31, 2016, a historical marker was erected here by the Equal Justice Initiative to commemorate these extra-judicial executions.[6]

Population in the rural county has declined by two thirds since the 1900 high of more than 35,000. The effects of farm mechanization and the boll weevil infestation, which decimated the cotton crops and reduced the need for farm labor in the 1920s and 1930s, caused widespread loss of jobs. In addition, many blacks left the county in order to escape the racial violence. In the first half of the 20th century, during the Great Migration to northern and midwestern industrial cities, blacks left Jim Crow to seek more freedom and work opportunities. Young people continue to leave for towns and cities.

Civil Rights Era

By 1960 (as shown on census tables below), the population had declined to about 15,000 residents and continued to be about four-fifths majority black. The rural county was referred to as "Bloody Lowndes," the rusty buckle of Alabama's Black Belt, because of the high rate of white violence against blacks to maintain segregation. In 1965, a century after the American Civil War and decades after whites had disenfranchised blacks via the 1901 state constitution, they maintained white supremacy by intimidation and violence.

County population had fallen by more than half from its 1900 high, as both blacks and whites moved to urban areas. Blacks still outnumbered whites by a 4 to 1 ratio.[7] Eighty-six white families owned 90 percent of the land in the county and controlled the government, as whites had since 1901. With an economy based on agriculture, black residents worked mostly in low-level rural jobs. In the civil rights era, not one black resident was registered to vote before March 1, 1965.[8]

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in August of that year encouraged civil rights leaders to believe they could fight racism in Lowndes. "The Lowndes County Freedom Organization" was founded in the county as a new, independent political party designed to help blacks stand up to intimidation and murder.[8]

Organized by the young civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), in the summer of 1965 Lowndes residents launched an intensive effort to register blacks in the county to vote.[9] SNCC's plan was simple: to get enough black people to vote so blacks might be fully represented in the local government and redirect services to black residents, 80 percent of whom lived below the poverty line. Carmichael and others organized registration drives, demonstrations, and political education classes in support of the black residents. The Voting Rights Act authorized the federal government to oversee voter registration and voting processes in places such as Lowndes County where substantial minorities were historically under-represented.

The police continued to arrest protesters in the summer of 1965. A group of protesters were released from jail in the county seat of Hayneville on August 20, 1965. As four of them approached a small store, Thomas Coleman, an unpaid special deputy, ordered them away. When he aimed his shotgun at one of the young black women, Jonathan Myrick Daniels pushed her down, taking the blast, which immediately killed the Episcopal seminarian. Coleman also shot Father Thomas Morrisroe, a Catholic priest, in the back, then stopped. He was indicted for the murder of Daniels; and an all-white jury quickly acquitted him after his claim of self-defense, although both men were unarmed. Coleman was appointed by the county sheriff.[7]

In 1966 after working to register African-American voters, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), the first independent black political party in the county since Reconstruction, recruited several local residents as candidates for county offices. It adopted the emblem of the black panther, in contrast to the white rooster of the white-dominated Alabama Democratic Party.[10][11]

Whites in Lowndes County reacted strongly against the LCFO. In retaliation for black sharecroppers engaging in civil rights work, white landowners evicted many of them from their rental houses and land plots. They used economic blackmail to make them both homeless and unemployed in a struggling economy. The SNCC and Lowndes County leaders worked to help these families stay together and remain in the county. They bought tents, cots, heaters, food, and water and helped several families build a temporary "Tent City." Despite harassment, including shots regularly fired into the encampment, these black residents persevered for nearly two years as organizers helped them find new jobs and look for permanent housing.[12]

Whites refused to serve known LCFO members in stores and restaurants. Several small riots broke out over the issue. The LCFO pushed forward and continued to organize and register voters.[10] However, none of their candidates won in the November 1966 general election. In a December 1966 edition of The Liberator, a Black Power magazine, activist Dr. Gwendolyn Patton alleged the election had been subverted by widespread ballot fraud.[13] But historians believe that black sharecroppers submitted to the severe pressure put on them by the local white plantation owners, who employed most of them.[14] After the LCFO folded into the statewide Democratic Party in 1970, African-American supported candidates have won election to local offices.[14] In a continuing divide, since the late 20th century, most white conservative voters in Alabama have shifted to the Republican Party.

In White v. Crook (1966), Federal District Judge Frank M. Johnson ruled in a class action suit brought on behalf of black residents of Lowndes County, who demonstrated they had been excluded from juries. Women of all races were excluded from juries by state statute. Johnson ordered that the state of Alabama must take action to recruit both male and female Blacks to serve on juries, as well as other women, according to their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. The suit was joined by other class members from other counties who dealt with similar conditions of exclusion from juries. It was "one of the first civil actions brought to remedy systematic exclusion of Negroes from jury service generally."[15]

The LCFO continued to fight for wider political participation. Their goal of democratic, community control of politics spread into the wider civil rights movement. The first black sheriff in the county to be elected since Reconstruction was John Hullett, elected in 1970.

Today an Interpretive Center in the county, maintained by the National Park Service, memorializes the Tent City and LCFO efforts in political organizing.[12]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 725 square miles (1,880 km2), of which 716 square miles (1,850 km2) is land and 9.2 square miles (24 km2) (1.3%) is water.[16]

Major highways

.svg.png) Interstate 65

Interstate 65 U.S. Highway 31

U.S. Highway 31 U.S. Highway 80

U.S. Highway 80 State Route 21

State Route 21 State Route 97

State Route 97 State Route 185

State Route 185 State Route 263

State Route 263

Adjacent counties

- Autauga County (north)

- Montgomery County (east)

- Crenshaw County (southeast)

- Butler County (south)

- Wilcox County (southwest)

- Dallas County (west)

National protected area

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1830 | 9,410 | — | |

| 1840 | 19,539 | 107.6% | |

| 1850 | 21,915 | 12.2% | |

| 1860 | 27,716 | 26.5% | |

| 1870 | 25,719 | −7.2% | |

| 1880 | 31,176 | 21.2% | |

| 1890 | 31,550 | 1.2% | |

| 1900 | 35,651 | 13.0% | |

| 1910 | 31,894 | −10.5% | |

| 1920 | 25,406 | −20.3% | |

| 1930 | 22,878 | −10.0% | |

| 1940 | 22,661 | −0.9% | |

| 1950 | 18,018 | −20.5% | |

| 1960 | 15,417 | −14.4% | |

| 1970 | 12,897 | −16.3% | |

| 1980 | 13,253 | 2.8% | |

| 1990 | 12,658 | −4.5% | |

| 2000 | 13,473 | 6.4% | |

| 2010 | 11,299 | −16.1% | |

| Est. 2015 | 10,458 | [17] | −7.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] 1790–1960[19] 1900–1990[20] 1990–2000[21] 2010–2015[1] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 11,299 people residing in the county. In terms of ethnicity, 73.5% identified as Black or African American, 25.3% White, 0.2% Native American, 0.1% Asian, 0.3% of some other race and 0.5% of two or more races. 0.8% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

As of the census[22] of 2000, there were 13,473 people, 4,909 households, and 3,588 families residing in the county. The population density was 19 people per square mile (7/km2). There were 5,801 housing units at an average density of 8 per square mile (3/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 73.37% Black or African American, 25.86% White, 0.11% Native American, 0.12% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.12% from other races, and 0.40% from two or more races. 0.63% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

According to the census[23] of 2000, the largest ancestry groups claimed by residents in Lowndes County were African 73.37%, English 20.14%, and Scots-Irish 3.1%.

There were 4,909 households out of which 35.40% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.90% were married couples living together, 25.70% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.90% were non-families. 24.60% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.40% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.73 and the average family size was 3.28.

In the county the population was spread out with 30.20% under the age of 18, 9.10% from 18 to 24, 27.10% from 25 to 44, 21.40% from 45 to 64, and 12.20% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 87.90 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 82.90 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $23,050, and the median income for a family was $28,935. Males had a median income of $27,694 versus $20,137 for females. The per capita income for the county was $12,457. About 26.60% of families and 31.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 41.70% of those under age 18 and 26.60% of those age 65 or over.

Government

In 2014 Lowndes County has a five-member county commission, elected from single-member districts. The county commission hires the county sheriff.

| Year | GOP | DNC | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 26.2% 1,751 | 73.1% 4,882 | 0.7% 50 |

| 2012 | 23.3% 1,754 | 76.5% 5,747 | 0.2% 18 |

| 2008 | 24.9% 1,809 | 74.9% 5,449 | 0.2% 20 |

| 2004 | 29.7% 1,786 | 70.3% 4,233 | 0.03% 2 |

| 2000 | 26.2% 1,638 | 73.0% 4,557 | 0.8% 48 |

Education

Lowndes County is served by Lowndes County Public Schools, which include:[25]

- Calhoun High School

- Central Elementary School

- Central High School

- Fort Deposit Elementary School

- Hayneville Middle School

- Jackson-Steele Elementary School

- Lowndes County Middle School.

Communities

Towns

- Benton

- Fort Deposit

- Gordonville

- Hayneville (county seat)

- Lowndesboro

- Mosses

- White Hall

Unincorporated communities

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Lowndes County, Alabama

- Properties on the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage in Lowndes County, Alabama

- Fort Deposit–Lowndes County Airport

- Battle of Holy Ground

- Calhoun Colored School

- Bates Turkey Farm

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "Lowndes County", Alabama Department of History and Archives

- ↑ Glenn Feldman, The Disfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136

- ↑ "Supplement: Lynchings by County/ Alabama: Lowndes", 2nd edition, from Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, 2015, Equal Justice Institute, Montgomery, Alabama

- 1 2 "EJI Dedicates Marker to Commemorate Lynchings in Letohatchee, Alabama", Equal Justice Initiative, 1 August 2016

- 1 2 "Thomas Coleman, 86, Dies; Killed Rights Worker in '65". The New York Times. 22 June 1997.

- 1 2 Lowndes County Freedom Organization - Study Guide

- ↑ Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama's Black Belt, New York University Press, 2009.

- 1 2 Lowndes County Freedom Organization | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed

- ↑ Document: Stokely Carmichael: Black Power (1966) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- 1 2 Dr. Gwendolyn Patton, "Lowndes County Freedom Organization: Political Education Primer", Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement, accessed 30 March 2014

- ↑

- 1 2 , Encyclopedia of Alabama

- ↑ White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp. 401 - Dist. Court, MD Alabama 1966

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ↑ "County Totals Dataset: Population, Population Change and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ↑ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 24, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ↑ Public Schools, Lowndes County. "Lowndes County Public Schools". Retrieved 2009-05-23.

Further reading

- Jeffries, Hasan Kwame. Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama's Black Belt (2010)

External links

|

Autauga County |  | ||

| Dallas County | |

Montgomery County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Wilcox County | Butler County | Crenshaw County |

Coordinates: 32°09′N 86°39′W / 32.150°N 86.650°W