Manbij

| Manbij منبج Minbic | |

|---|---|

| |

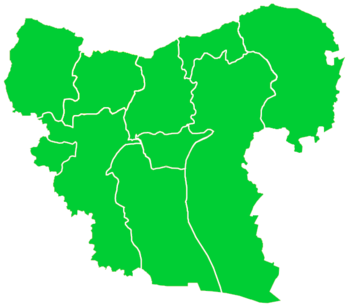

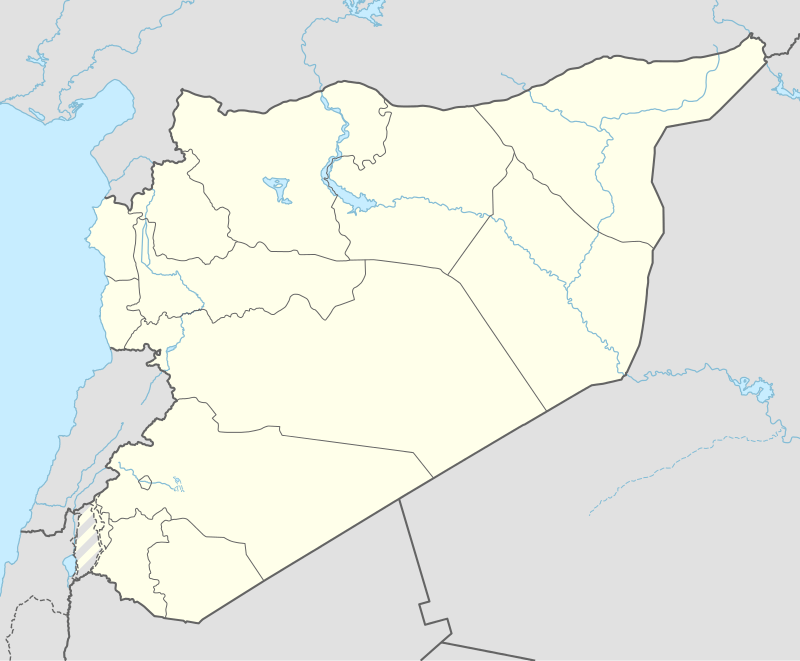

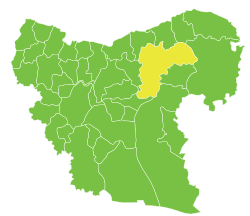

Manbij Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 36°32′N 37°57′E / 36.533°N 37.950°E | |

| Country |

|

| Governorate |

Aleppo Governorate (de jure) Shahba Canton (de facto) |

| District | Manbij |

| Subdistrict | Manbij |

| Occupation | Syrian Democratic Forces |

| Elevation | 460 m (1,510 ft) |

| Population (2009) | |

| • Total | 74,575 |

Manbij (Arabic: منبج; ALA-LC: Manbij, Adyghe: Mumbuj, Kurdish: Mabuk or Minbic,[1][2][3] Turkish: Münbiç, Syriac: ܡܒܘܓ Mabbug, Greek: Hierapolis or Bambyce)[4][5] is a city in the Aleppo Governorate, Syria, 30 kilometers west of the Euphrates. In the 2004 census by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Manbij had a population of nearly 100,000.[6] Its inhabitants are predominantly Sunni Muslims of Arab ethnicity with small number of Turkmen, Kurdish and Circassian ethnicity.[7] As a preliminary result of the ongoing Syrian Civil War, Manbij today is situated in Shahba region within the de facto autonomous Federation of Northern Syria – Rojava framework.

Etymology

Coins struck at the city before Alexander's conquest record the Aramean name of the city as Mnbg (meaning spring site).[8] For the Assyrians it was known as Nappigu (Nanpigi).[9] The place appears in Greek as Bambyce and Pliny (v. 23) tells us its Syrian name was Mabog (also Mabbog, Mabbogh). As a center of the worship of the Syrian goddess Atargatis, it became known to the Greeks as the Ἱερόπολις (Hieropolis) 'city of the sanctuary', and finally as Ἱεράπολις (Hierapolis) 'holy city'.

Cult of Atargatis

This worship of Atargatis was immortalized in De Dea Syria which has traditionally been attributed to Lucian of Samosata, who gave a full description of the religious cult of the shrine and the tank of sacred fish of Atargatis, of which Aelian also relates marvels. According to the De Dea Syria, the worship was of a phallic character, votaries offering little male figures of wood and bronze. There were also huge phalli set up like obelisks before the temple, which were ceremoniously climbed once a year and decorated.

The temple contained a holy chamber into which only priests were allowed to enter. A great bronze altar stood in front, set about with statues, and in the forecourt lived numerous sacred animals and birds (but not swine) used for sacrifice.

Some three hundred priests served the shrine and there were numerous minor ministrants. The lake was the centre of sacred festivities and it was customary for votaries to swim out and decorate an altar standing in the middle of the water. Self-mutilation and other orgies went on in the temple precinct, and there was an elaborate ritual on entering the city and first visiting the shrine.

History

Antiquity

The Arameans called the city "Mnbg" (Manbug).[10] Manbij was part of the kingdom of Bit Adini and was annexed by the Assyrians in 856 BC. The Assyrian king Shalmaneser III renamed it Lita-Ashur and built a royal palace. The city was reconquered by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III in 738 BC.[11] The sanctuary of Atargatis predate the Macedonian conquest as it seems that the city was the center of a dynasty of Aramean priest-kings ruling at the very end of the Achaemenid Empire;[12] two kings are known, 'Abyati and Abd-Hadad.[13][14] The fate of Abd-Hadad is not known but the city came firmly under the Macedonian empire,[15] and prospered under the rule of the Seleucids who made it the chief station on their main road between Antioch and Seleucia on the Tigris. The temple was sacked by Crassus on his way to meet the Parthians (53 BC). The coinage of the city begins in the 4th century BC with the coins of the priest-kings followed by the Aramaic series of the Macedonian and Seleucid monarchs. They show Atargatis either as a bust with mural crown or as riding on a lion. She continues to supply the chief type even during imperial Roman times, being generally shown seated with the tympanum in her hand. Other coins substitute the legend Θεᾶς Συρίας Ἱεροπολιτῶν within a wreath.

In the 3rd century, the city was the capital of Euphratensis province and one of the great cities of Syria. Procopius called it the greatest in that part of the world. It was, however, in ruinous state when Julian gathered his troops there before marching to his defeat and death in Mesopotamia. Sassanid Emperor Khosrau I held it to ransom after Byzantine Emperor Justinian I had failed to defend it.

Middle Ages

The Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid restored Manbij at the end of the 8th century, making it the capital of al-Awasim (Byzantine frontier province).[16] Afterward, the city became a point of contention between the Byzantines, Arabs and Turkic groups. The Arab chieftain Salih ibn Mirdas captured it circa 1022, making Manbij, along with Balis and al-Rahba, the foundation of his future Mirdasid emirate.[17] At the time, Manbij was one of the most important fortresses in northern Syria.[18] In 1068, the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes captured it, defeated the Mirdasids and their Bedouin allies, killed the city's inhabitants and plundered the surrounding countryside.[19] Romanos later withdrew due to a severe shortage of food and supplies.[18][19]

The Crusaders never captured Manbij during their 11th–12th century invasions of the Levant, but the Latin archbishopric of Hierapolis was reestablished in the town of Duluk by 1134.[20] By 1152, Duluk and Manbij were captured by the Zengids under Nur ad-Din,[20] who reconstructed and strengthened the city's fortress.[21] The Ayyubid sultan, Saladin, conquered it from its Zengid lord, Qutb ad-Din Inal, in 1175.[22] In 1260, the Mongols under Hulagu destroyed Ayyubid Manbij, which was consequently abandoned by its then-Turkmen inhabitants.[23]

Modern era

The remains of ancient Manbij are extensive, but almost wholly of late date, as is to be expected in the case of a city which survived into Muslim times. The walls were built by the Arabs, and no ruins of the great temple survive. The most noteworthy relic of antiquity is the sacred lake, on two sides of which can still be seen stepped quays and water-stairs. The first modern western account of the site is in Henry Maundrell's Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem, 1699. Under the Ottoman Empire, Manbij was a kaza of the sanjak and vilayet of Aleppo. In 1879, after the Russo-Turkish War, a colony of Circassians from Vidin (Widdin) was planted in the ruins, from which many antiquities were excavated and sold in bazaars of Aleppo and Aintab.[24] As of 1911, its 1,500 inhabitants were all Circassians.[25]

Syrian Civil War

Prior to and in the early years of the Syrian Civil War, Manbij had an ethnically diverse population of Arab, Kurdish and Circassian Sunni Muslims, many of whom followed the Naqshbandi Sufi order. The city's socio-political life was dominated by its main tribes. Tribal leaders served as the mediators and arbiters of major disputes in Manbij, while the state's security forces largely dealt with petty offenses. The city was relatively liberal compared to other Sunni Muslim-majority cities in the countryside of Aleppo.[7]

During the civil war, on 20 July 2012, Manbij fell to local rebel forces who thereafter administered the city. ln December, there was an election to appoint a local council.[26] In January 2014, forces from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) took over the city after ousting the rebels. The city has since become a hub for trading in looted artifacts and archaeological digging equipment.[27] In June 2016, the SDF launched an offensive to capture Manbij,[28] and by June 8 had fully encircled the city.[29] On 12 August the SDF had established full control over Manbij after a two-month battle.[30]

By 15 August, thousands of previously displaced citizens of Manbij were reported returning.[31] On 19 August 2016, the Manbij Military Council issued a written statement announcing it had taken over the security of Manbij city center and villages from the Syrian Democratic Forces, of which it is a component.[32]

Today Manbij is self-administered by the Manbij City Council, co-chaired by Sheikh Farouk al-Mashi and Salih Haji Mohammed,[33] as part of Shahba region within the de facto autonomous Federation of Northern Syria – Rojava framework. While public administration including public schools has regained secular normalcy after the ISIL episode,[34][35] a reconciliation committee to overcome rifts created by the civil war was formed,[36] and international humanitarian aid has been delivered,[37] the democratic confederalist political program of Rojava is driving political and societal transformations in terms of direct democracy and gender equality.[38][39] Reconstruction after devastations of civil war combat[40] remains a major challenge.

Ecclesiastical history

Lequien names ten bishops of Hierapolis.[41] Among the best-known are Alexander of Hierapolis, an ardent advocate of Nestorianism, who died in exile in Egypt; Philoxenus of Mabbug, a famous Miaphysite scholar; and Stephen of Hierapolis (c. 600), author of a life of St. Golindouch. In the sixth century, the metropolitan see had nine suffragan bishoprics.[42] Chabot mentions thirteen Jacobite archbishops from the ninth to the twelfth century.[43] One Latin bishop, Franco, in 1136, is known.[25][44]

Climate

Manbij has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate with influences of a continental climate during winter with hot dry summers and cool wet and occasionally snowy winters. The average high temperature in January is 7.8 °C (46.0 °F) and the average high temperature in August is 38.1 °C (100.6 °F) . The snow falls usually in January, February or December.

| Climate data for Manbij | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

38.1 (100.6) |

33.2 (91.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

23.31 (73.95) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.2 (45) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

9.39 (48.89) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69 (2.72) |

54 (2.13) |

38 (1.5) |

28 (1.1) |

8 (0.31) |

3 (0.12) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.12) |

25 (0.98) |

36 (1.42) |

58 (2.28) |

322 (12.68) |

| Average rainy days | 10 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 46 |

| Average snowy days | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 63 | 56 | 52 | 38 | 36 | 31 | 31 | 39 | 43 | 51 | 70 | 48.4 |

| Source: Weather Online, Weather Base, BBC Weather and My Weather 2 | |||||||||||||

Transportation

Manbij is served by two major roads, Route M4 and Route 216.

There is no airport near Manbij, the nearest is in Aleppo.

Notes

- ↑ "PYD, Menbiç'te Özerkliğe Hazırlanıyor! Şehrin Adı 'Mabuk' Oldu". Haberler.com. 11 June 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ↑ Abbas, Ala (13 June 2016). "مابوك الكردية أم منبج العربية؟ (Kurdish Mabuk or Arabic Manbij)". Qasioun.net. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ↑ "Muslim bi Meclîsa Minbicê re rûnişt". Hawar News Agency (ANHA). 26 May 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ Grant, Michael (1996). The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition. Psychology Press. p. 93. ISBN 9780415138147.

- ↑ Winter, Irene (2009). On Art in the Ancient Near East Volume I: Of the First Millennium BCE. BRILL. p. 564. ISBN 9789047425847.

- ↑ General Census of Population and Housing 2004. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Aleppo Governorate.(Arabic)

- 1 2 Khaddour, Kheder; Mazur, Kevin (Winter 2013). "The Struggle for Syria's Regions". Middle East Research and Information Project. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 498.

- ↑ Irene Winter (2009). On Art in the Ancient Near East Volume I: Of the First Millennium BCE. p. 564.

- ↑ Jonas Carl Greenfield (2001). 'Al Kanfei Yonah. p. 285.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 479.

- ↑ Fergus Millar (1993). The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337. p. 244.

- ↑ Edward Lipiński (2000). The Aramaeans: Their Ancient History, Culture, Religion. p. 633.

- ↑ Kevin Butcher (2004). Coinage in Roman Syria: Northern Syria, 64 BC-AD 253. p. 24.

- ↑ John D Grainger (2014). Seleukos Nikator (Routledge Revivals): Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom. p. 147.

- ↑ Cobb, Paul M. (2001). White Banners: Contention in 'Abbasid Syria, 750-880. SUNY Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780791448809.

- ↑ Zakkar, Suhayl (1971). The Emirate of Aleppo: 1004–1094. Aleppo: Dar al-Amanah. p. 53.

- 1 2 Basan, Osman Aziz (2010). The Great Seljuqs: A History. Routledge. p. 76.

- 1 2 Ibn al-Athir (2002). Richards, D.S., ed. The Annals of the Saljuq Turks: Selections from Al-Kamil Fi'l-Ta'rikh of Ibn Al-Athir. Routledge. p. 166.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Bernard (2006). "The Growth of the Latin Church of Antioch". In Ciggaar, K.; Metcalf, M. East and West in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean: Antioch from the Byzantine Reconquest Until the End of the Crusader Principality. Peeters Publishers. pp. 175, 180.

- ↑ Hillenbrand, Carole (2000). The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Routledge. p. 474.

- ↑ Lyons, Malcolm Cameron; Jackson, D. E. P. (1982). Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War. Cambridge University Press. p. 105.

- ↑ Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (1995). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260-128. Cambridge University Press. p. 204.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica 11th Edition

- 1 2 Catholic Encyclopedia

- ↑ "المجالس المحلية .. خطوة نحو الأمام". SyriaTomorrow. 9 December 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ "Al Qaeda chief Zawahri tells Islamists in Syria to unite - audio". Reuters. 2015-01-23. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ "SDF closes in on ISIL supply route in Syria's Manbij". Al Jazeera. 3 June 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ "U.S.-backed forces cut off all routes into IS-held Manbij: Syrian Observatory". Reuters. 8 June 2016.

- ↑ Charkatli, Izat (2016-08-12). "SDF captures ISIS's largest stronghold in Aleppo". Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ "Thousands Return To Manbij After Islamic State Militants Flee City". News Deeply. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ "Manbij Military Council takes over the security of Manbij". ANF. 19 August 2016.

- ↑ "On the Front Line in the Bloody Fight to Take Manbij From ISIS". The Daily Beast. 5 June 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ "Syrian kids relish return to school in ex-IS bastion". ReliefWeb (AFP). 28 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ "Manbij: students back to school after ISIS explosives dismantled". ARA News. 10 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ "Reconciliation committee formed of Manbij tribal notables and intellectuals". ANHA. 9 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ "US-led coalition delivering aid to civilians in post-ISIS Manbij". ARA News. 25 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ "Syrian women liberated from Isis are joining the police to protect their city". The Independent. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ "Liberated from ISIS suppression, women of Manbij join security forces (includes Video)". ARA News. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ "(Video) Manbij after liberation". 23 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- ↑ Or. Christ. II 925-8

- ↑ Echos d'Orient 14:145

- ↑ Revue de l'orient chrétien VI:200

- ↑ Lequien, III, 1193

References

- The Syrian Goddess (1913) at sacred-texts.com

- F. R. Chesney, Euphrates Expedition (1850)

- W. F. Ainsworth, Personal Narrative of the Euphrates Expedition (1888)

- E. Sachau, Reise in Syrien, &c. (1883)

- D. G. Hogarth in Journal of Hellenic Studies (1909)

- Henry Maundrell (1836). A Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem, at Easter, A.D. 1697: To which is Added an Account of the Author's Journey to the Banks of the Euphrates at Beer, and to the Country of Mesopotamia. Boston: S. G. Simpkins. 271 pages

- le Strange, Guy (1890), Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund p. 36, 39, 42, 500

Coordinates: 36°31′39″N 37°57′19″E / 36.52750°N 37.95528°E