Tell Brak

Tell Brak as seen from a distance with several excavation areas visible | |

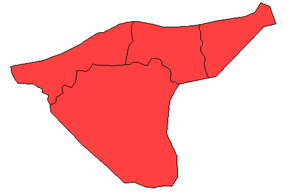

Shown within Syria | |

| Alternate name | Nagar, Nawar |

|---|---|

| Location | Al-Hasakah Governorate, Syria |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 36°40′03.42″N 41°03′31.12″E / 36.6676167°N 41.0586444°ECoordinates: 36°40′03.42″N 41°03′31.12″E / 36.6676167°N 41.0586444°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 40 hectares (99 acres).[1] |

| Height | 40 metres (130 ft).[1] |

| History | |

| Periods | Neolithic, Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Halaf culture, Northern Ubaid, Uruk, Kish civilization, Hurrian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1937–1938, 1976–2011.[1] |

| Archaeologists | Max Mallowan, David Oates, Joan Oates |

| Public access | yes |

| Website | tellbrak.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk |

Tell Brak (Nagar, Nawar) was an ancient city in Syria. Its remains constitute a tell located in the Upper Khabur region, near the modern village of Tell Brak, 50 kilometers north-east of Al-Hasaka city, Al-Hasakah Governorate. The city's original name is unknown. During the second half of the third millennium BC, the city was known as Nagar and later on, Nawar.

Starting as a small settlement in the seventh millennium BC, Tell Brak evolved during the fourth millennium BC into one of the biggest cities in Northern Mesopotamia, and interacted with the cultures of southern Mesopotamia. The city shrank in size at the beginning of the third millennium BC with the end of Uruk period, before expanding again around c. 2600 BC, when it became known as Nagar, and was the capital of a regional kingdom that controlled the Khabur river valley. Nagar was destroyed around c. 2300 BC, and came under the rule of the Akkadian Empire, followed by a period of independence as a Hurrian city-state, before contracting at the beginning of the second millennium BC. Nagar prospered again by the 19th century BC, and came under the rule of different regional powers. In c. 1500 BC, Tell Brak was a center of Mitanni before being destroyed by Assyria c. 1300 BC. The city never regained its former importance, remaining as a small settlement, and abandoned at some points of its history, until disappearing from records during the early Abbasid era.

Different peoples inhabited the city, including the Halafians, Semites and the Hurrians. Tell Brak was a religious center from its earliest periods; its famous Eye Temple is unique in the Fertile Crescent, and its main deity, Belet-Nagar, was revered in the entire Khabur region, making the city a pilgrimage site. The culture of Tell Brak was defined by the different civilizations that inhabited it, and it was famous for its glyptic style, equids and glass. When independent, the city was ruled by a local assembly or by a monarch. Tell Brak was a trade center due to its location between Anatolia, the Levant and southern Mesopotamia. It was excavated by Max Mallowan in 1937, then regularly by different teams between 1979 and 2011, when the work stopped due to the Syrian Civil War.

History

Tell Brak is the current name of the tell.[2] East of the mound lies a dried lake named "Khatuniah" which was recorded as "Lacus Beberaci" (the lake of Brak) in the Roman map Tabula Peutingeriana.[3] The lake was probably named after Tell Brak which was the nearest camp in the area.[4] The name "Brak" might therefore be an echo of the most ancient name which is unknown.[3]

Early settlement

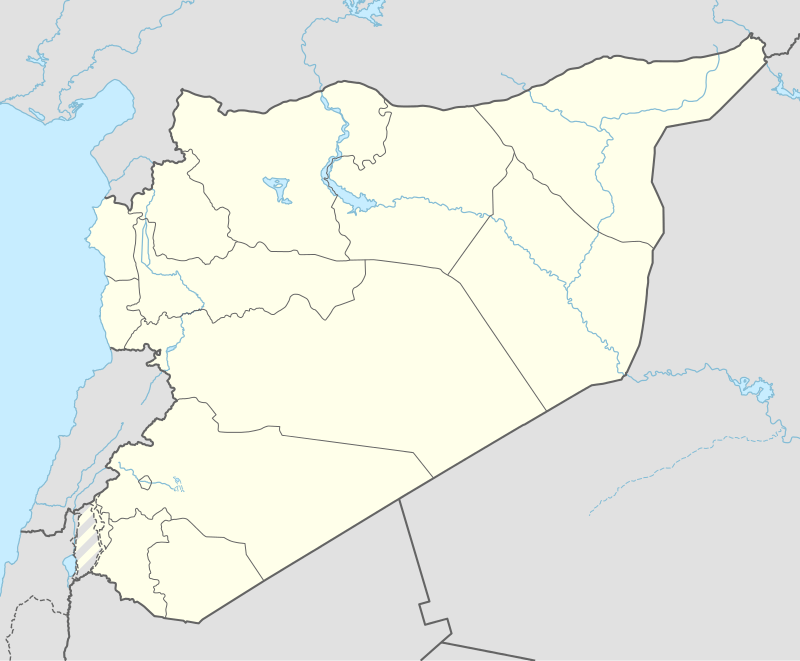

The earliest period A, is dated to the proto Halaf culture c. 6500 BC, when a small settlement existed.[5] Many objects dated to that period were discovered including the Halaf pottery.[6] By 5000 BC,[7] Halaf culture transformed into Northern Ubaid,[8] and many Ubaid materials were found in Tell Brak.[5] Excavations and surface survey of the site and its surroundings, unearthed a large platform of patzen bricks that dates to late Ubaid,[note 1][5] and revealed that Tell Brak developed as an urban center slightly earlier than better known cities of southern Mesopotamia, such as Uruk.[10][11]

The first city

In southern Mesopotamia, the original Ubaid culture evolved into the Uruk period.[12] The people of the southern Uruk period used military and commercial means to expand the civilization.[13] In Northern Mesopotamia, the post Ubaid period is designated Late Chalcolithic / Northern Uruk period,[14] during which, Tell Brak, whose original name is unknown,[15] started to expand.[5]

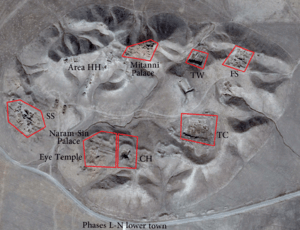

Period Brak E witnessed the building of the city's walls,[16] and Tell Brak expansion beyond the mound to form a lower town.[5] By the late 5th millennium BC, Tell Brak reached the size of c. 55 hectares.[5] Area TW of the tell (see the map for Tell Brak's areas) revealed the remains of a monumental building with two meters thick walls and a basalt threshold.[5] In front of the building, a sherd paved street was discovered, leading to the northern entrance of the city.[5]

The city continued to expand during period F, and reached the size of 130 hectares.[5] Four mass graves dating to c. 3800–3600 BC were discovered in the surroundings of the tell, and they suggest that the process of urbanization was accompanied by internal social stress, and an increase in the organization of warfare.[17] The first half of period F (designated LC3), saw the erection of the Eye Temple,[note 2][5] which was named for the thousands of small alabaster "Eye idols" figurines discovered in it.[note 3][23] Those idols were also found in area TW.[24]

Interactions with the Mesopotamian south grew during the second half of period F (designated LC4) c. 3600 BC,[5] and an Urukean colony was established in the city.[25][26] With the end of Uruk culture c 3000 BC, Tell Brak's Urukean colony was abandoned and deliberately leveled by its occupants.[27][28] Tell Brak contracted during the following periods H and J, and became limited to the mound.[5] Evidence exists for an interaction with the Mesopotamian south during period H, represented by the existence of materials similar to the ones produced during the southern Jemdet Nasr period.[29] The city remained a small settlement during the Ninevite 5 period, with a small temple and associated sealing activities.[note 4][5]

Kingdom of Nagar

| Nagar | ||||||||

| ||||||||

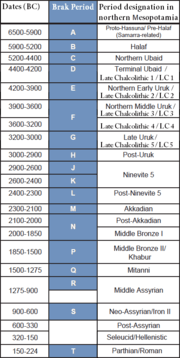

The kingdom of Nagar c. 2340 BC | ||||||||

| Capital | Nagar | |||||||

| Languages | Nagarite | |||||||

| Religion | Mesopotamian | |||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | |||||||

| • | Established | c. 2600 BC | ||||||

| • | Disestablished | c. 2300 BC | ||||||

| ||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||

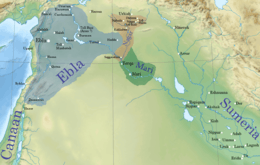

Around c. 2600 BC, a large administrative building was built and the city expanded out of the tell again.[5] The revival is connected with the Kish civilization,[34] and the city was named "Nagar", which might be of Semitic origin and mean a "cultivated place".[35] Amongst the important buildings dated to the kingdom, is an administrative building or temple named the "Brak Oval", located in area TC.[36] The building have a curved exterior wall reminiscent of the Khafajah "Oval Temple" in central Mesopotamia.[36] However, aside from the wall, the comparison between the two buildings in terms of architecture is difficult, as each building follows a different plan.[36]

The oldest references to Nagar comes from Mari and tablets discovered at Nabada.[37] However, the most important source on Nagar come from the archives of Ebla.[38] Most of the texts record the ruler of Nagar using his title "En", without mentioning a name.[37][38] However, the text from Mari record king Amar-An, who could be identical to Mara-Il, a king of Nagar mentioned in one of Ebla's texts.[note 5][37] Thus, Mara-Il is the only king known by name for pre-Akkadian Nagar, he ruled a little more than a generation before the kingdom's destruction,[41] and was most probably the "En" recorded in the other texts, including the ones from Nabada.[38]

At its height, Nagar encompassed most of the southwestern half of the Khabur Basin,[41] and was a diplomatic and political equal of the Eblaite and Mariote states.[42] The kingdom included many subordinate cities such as Hazna,[43] and most importantly Nabada, which was a city-state annexed by Nagar,[44] and served as a provincial capital.[45] Nagar was involved in the wide diplomatic network of Ebla,[34] and the relations between the two kingdoms involved both confrontations and alliances.[38] A text from Ebla mention a victory of Ebla's king (perhaps Irkab-Damu) over Nagar.[38] However, a few years later, a treaty was concluded, and the relations progressed toward a dynastic marriage between princess Tagrish-Damu of Ebla, and prince Ultum-Huhu, Nagar's monarch's son.[35][38]

Nagar was defeated by Mari in year seven of the Eblaite vizier Ibrium's term, causing the blockage of trade routes between Ebla and southern Mesopotamia via upper Mesopotamia.[46] Later, Ebla's king Isar-Damu concluded an alliance with Nagar and Kish against Mari,[47] and the campaign was headed by the Eblaite vizier Ibbi-Sipish, who led the combined armies to victory in a battle near Terqa.[48] Afterwards, the alliance attacked the rebellious Eblaite vassal city of Armi.[49] Ebla was destroyed approximately three years after Terqa's battle,[50] and soon after, Nagar followed in c. 2300 BC.[51] Large parts of the city were burned, an act attributed either to Mari,[52] or Sargon of Akkad.[51]

Akkadian period

Following its destruction, Nagar was rebuilt by the Akkadian empire, to form a center of the provincial administration.[53] The city included the whole tell and a lower town at the southern edge of the mound.[5] Two public buildings were built during the early Akkadian periods, one complex in area SS,[53] and another in area FS.[54] The building of area FS included its own temple and might have served as a caravanserai, being located near the northern gate of the city.[55] The early Akkadian monarchs were occupied with internal conflicts,[56] and Tell Brak was temporarily abandoned by Akkad at some point preceding the reign of Naram-Sin.[note 6][59] The abandonment might be connected with an environmental event, that caused the desertification of the region.[59]

The destruction of Nagar's kingdom created a power vacuum in the Upper Khabur.[60] The Hurrians, formerly concentrated in Urkesh,[61] took advantage of the situation to control the region as early as Sargon's latter years.[60] Tell Brak was known as "Nawar" for the Hurrians,[note 7][64] and kings of Urkesh took the title "King of Urkesh and Nawar", first attested in the seal of Urkesh's king Atal-Shen.[65][66]

The use of the title continued during the reigns of Atal-Shen's successors, Tupkish and Tish-Atal,[61][67] who ruled only in Urkesh.[68] The Akkadians under Naram-Sin incorporated Nagar firmly into their empire.[69] The most important Akkadian building in the city is called the "Palace of Naram-Sin",[note 8][69] which had parts of it built over the original Eye Temple.[70][71] Despite its name, the palace is closer to a fortress,[69] as it was more of a fortified depot for the storage of collected tribute rather than a residential seat.[72][73] The palace was burned during Naram-Sin's reign, perhaps by a Lullubi attack,[51] and the city was burned toward the end of the Akkadian period c. 2193 BC, probably by the Gutians.[51]

Post-Akkadian kingdom

The Akkadian period was followed by period N,[74] during which Nagar was the center of an independent Hurrian dynasty,[75] evidenced by the discovery of a seal, recording the name of king Talpus-Atili of Nagar,[76] who ruled during or slightly after the reign of Naram-Sin's son Shar-Kali-Sharri.[77] The view that Tell Brak came under the control of Ur III is refused,[note 9][79] and evidence exists for a Hurrian rebuilding of Naram-Sin's palace, erroneously attributed by Max Mallowan to Ur-Nammu of Ur.[80] Period N saw a reduction in the city's size, with public buildings being abandoned, and the lower town evacuated.[81] Few short lived houses were built in area CH during period N,[81] and although greatly reduced in size, archaeology provided evidence for continued occupation in the city, instead of abandonment.[note 10][5]

Foreign rule and later periods

During period P, Nagar was densely populated in the northern ridge of the tell.[5] The city came under the rule of Mari,[85] and was the site of a decisive victory won by Yahdun-Lim of Mari over Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria.[86] Nagar lost its importance and came under the rule of Kahat in the 18th century BC.[87] The name "Nagar" ceased occurring following the Old Babylonian period,[87] however, the city continued to exist as Nawar, under the control of Mitanni.[88]

During period Q, Tell Brak was an important trade city in the Mitanni state.[89] A two story palace was built c. 1500 BC in the northern section of the tell,[5][90] in addition to an associated one roomed temple.[91] However, the rest of the tell was not occupied, and a lower town extended to the north but is now all but destroyed through modern agriculture.[5] Two Mitannian legal documents, bearing the names of kings Artashumara and Tushratta, were recovered from the city,[92] which was destroyed between c.1300 and 1275 BC,[5] in two waves, first at the hands of the Assyrian king Adad-Nirari I, then by his successor Shalmaneser I.[93]

Little evidence of an occupation on the tell exists following the destruction of the Mitannian city, however, a series of small villages existed in the lower town during the Assyrian periods.[5] The remains of a Hellenistic settlement were discovered on a nearby satellite tell, to the northwestern edge of the main tell.[5] However, excavations recovered no ceramics of the Parthian-Roman or Byzantine-Sasanian periods, although sherds dating to those periods are noted.[5] In the middle of the first millennium AD, a fortified building was erected in the northeastern lower town.[5] The building was dated by Antoine Poidebard to the Justinian era (sixth century AD), on the basis of its architecture.[5] The last occupation period of the site was during the early Abbasid Caliphate's period, when a canal was built to provide the town with water from the nearby Jaghjagh River.[5]

Society

People and language

.jpg)

The Halafians were the indigenous people of Neolithic northern Syria,[note 11][96] who later adopted the southern Ubaidian culture.[8] Contact with the Mesopotamian south increased during the early and middle Northern Uruk period,[18] and southern people moved to Tell Brak in the late Uruk period,[97] forming a colony, which produced a mixed society.[29] The Urukean colony was abandoned by the colonist toward the end of the fourth millennium BC, leaving the indigenous Tell Brak a much contracted city.[98][99] The pre-Akkadian kingdom's population was Semitic,[100] and spoke its own East Semitic dialect of the Eblaite language used in Ebla and Mari.[101] The Nagarite dialect is closer to the dialect of Mari rather than that of Ebla.[45]

No Hurrian names are recorded in the pre-Akkadian period,[56][102] although the name of prince Ultum-Huhu is difficult to understand as Semitic.[103] During the Akkadian period, both Semitic and Hurrian names were recorded,[54][100] as the Hurrians appears to have taken advantage of the power vacuum caused by the destruction of the pre-Akkadian kingdom, in order to migrate and expand in the region.[60] The post-Akkadian period Tell Brak had a strong Hurrian element,[104] and Hurrian named rulers,[100] although the region was also inhabited by Amorite tribes.[105] A number of the Amorite Banu-Yamina tribes settled the surroundings of Tell Brak during the reign of Zimri-Lim of Mari,[105] and each group used its own language (Hurrian and Amorite languages).[105] Tell Brak was a center of the Hurrian-Mitannian empire,[92] which had Hurrian as its official language.[106] However, Akkadian was the region's international language, evidenced by the post-Akkadian and Mitannian eras tablets,[107][108] discovered at Tell Brak and written in Akkadian.[109]

Religion

The findings in the Eye Temple indicate that Tell Brak is among the earliest sites of organized religion in northern Mesopotamia.[110] It is unknown to which deity the Eye Temple was dedicated,[15] and the "Eyes" figurines appears to be votive offerings to that unknown deity.[18] Michel Meslin hypothesized that the temple was the center of the Sumerian Innana or the Semitic Ishtar, and that the "Eyes" figurines were a representation of an all-seeing female deity.[111]

During the pre-Akkadain kingdom's era, Hazna, an old cultic center of northern Syria, served as a pilgrimage center for Nagar.[112][113] The Eye Temple remained in use,[114] but as a small shrine,[115] while the goddess Belet-Nagar became the kingdom's paramount deity.[note 12][114] The temple of Belet-Nagar is not identified but probably lies beneath the Mitannian palace.[5] The Eblaite deity Kura was also venerated in Nagar,[103] and the monarchs are attested visiting the temple of the Semitic deity Dagon in Tuttul.[38] During the Akkadian period, the temple in area FS was dedicated to the Sumerian god Shakkan, the patron of animals and countrysides.[55][118][119] Tell Brak was an important religious Hurrian center,[120] and the temple of Belet-Nagar retained its cultic importance in the entire region until the early second millennium BC.[note 13][35]

Culture

Northern Mesopotamia evolved independently from the south during the Late Chalcolithic / early and middle Northern Uruk (4000-3500 BC).[25] This period was characterized by a strong emphasis on holy sites,[122] among which, the Eye Temple was the most important in Tell Brak.[123] The building containing "Eyes" idols in area TW was wood paneled, whose main room had been lined with wooden panels.[5] The building also contained the earliest known semi columned facade, which is a character that will be associated with temples in later periods.[5]

By late Northern Uruk and especially after 3200 BC, northern Mesopotamia came under the full cultural dominance of the southern Uruk culture,[25] which affected Tell Brak's architecture and administration.[97] The southern influence is most obvious in the level named the "Latest Jemdet Nasr" of the Eye Temple,[20] which had southern elements such as cone mosaics.[124] The Uruk presence was peaceful as it is first noted in the context of feasting; commercial deals during that period were traditionally ratified through feasting.[note 14][97][126] The excavations in area TW revealed feasting to be an important local habit, as two cooking facilities, large amounts of grains, skeletons of animals, a domed backing oven and barbequing fire pets were discovered.[127] Among the late Uruk materials found at Tell Brak, is a standard text for educated scribes (the "Standard Professions" text), part of the standardized education taught in the 3rd millennium BC over a wide area of Syria and Mesopotamia.[11]

The pre-Akkadian kingdom was famed for its acrobats, who were in demand in Ebla and trained local Eblaite entertainers.[41] The kingdom also had its own local glyptic style called the "Brak Style",[128] which was distinct from the southern sealing variants, employing soft circled shapes and sharpened edges.[129] The Akkadian administration had little effect on the local administrative traditions and sealing style,[130] and Akkadian seals existed side by side with the local variant.[131] The Hurrians employed the Akkadian style in their seals, and Elamite seals were discovered, indicating an interaction with the western Iranian Plateau.[131] Tell Brak provided great knowledge on the culture of Mitanni, which produced glass using sophisticated techniques, that resulted in different varieties of multicolored and decorated shapes.[92] Samples of the elaborate Nuzi ware were discovered, in addition to seals that combine distinctive Mitannian elements with the international motifs of that period.[92]

Wagons

Seals from Tell Brak and Nabada dated to the pre-Akkadian kingdom, revealed the use of four-wheeled wagons and war carriages.[132] Excavation in area FS recovered clay models of equids and wagons dated to the Akkadian and post-Akkadian periods.[132] The models provides information about the types of wagons used during that period (2350-2000 BC),[133] and they include four wheeled vehicles and two types of two wheeled vehicles; the first is a cart with fixed seats and the second is a cart where the driver stands above the axle.[89] The chariots were introduced during the Mitanni era,[89] and none of the pre-Mitanni carriages can be considered chariots, as they are mistakenly described in some sources.[89][133]

Government

The first city had the characteristics of large urban centers, such as monumental buildings,[134] and seems to have been ruled by a kinship based assembly, headed by elders.[135] The pre-Akkadian kingdom was decentralized,[136] and the provincial center of Nabada was ruled by a council of elders, next to the king's representative.[137][138] The Nagarite monarchs had to tour their kingdom regularly in order to assert their political control.[136][139] During the early Akkadian period, Nagar was administrated by local officials.[54] However, central control was tightened and the number of Akkadian officials increased, following the supposed environmental event that preceded the construction of Naram-Sin's palace.[140] The post-Akkadian Nagar was a city-state kingdom,[141] that gradually lost its political importance during the early second millennium BC, as no evidence for a king dating to that period exists.[86]

Rulers of Tell Brak

| King | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Early period, possibly ruled by a local assembly of elders.[135] | ||

| Pre-Akkadian kingdom of Nagar (c. 2600-2300 BC) | ||

| Mara-Il | Fl. late 24th century BC.[41] | |

| Early Akkadian period, early 23rd century BC.[53] | ||

| Urkesh dominance, the Urkeshite king Atal-Shen styled himself "King of Urkesh and Nawar",[142] so did his successors who ruled only in Urkesh.[68] | ||

| Akkadian control, under the rule of Naram-Sin of Akkad.[69] | ||

| Post-Akkadian kingdom of Nagar | ||

| Talpus-Atili | Fl. end of the third millennium BC.[143] | Styled himself "the sun of the country of Nagar".[60] |

| Various foreign rulers such as Mari,[85] Kahat,[87] Mitanni,[89] and Assyria.[144] | ||

Economy

Throughout its history, Tell Brak was an important trade center; it was an enterpot of obsidian trade during the Chalcolithic, as it was situated on the river crossing between Anatolia, the Levant and southern Mesopotamia.[145] The countryside was occupied by smaller towns, villages and hamlets, but the city's surroundings were empty within three kilometers.[5] This was probably due to the intensive cultivation in the immediate hinterland, in order to sustain the population.[5] The city manufactured different objects, including chalices made of obsidian and white marble,[17] faience,[146] flint tools and shell inlays.[147] However, evidence exists for a slight shift in production of goods toward manufacturing objects desired in the south, following the establishment of the Uruk colony.[97]

Trade was also an important economic activity for the pre-Akkadian kingdom of Nagar,[57] which had Ebla and Kish as major partners.[57] The kingdom produced glass,[146] wool,[41] and was famous for breeding and trading in the Kunga,[148][149] a hybrid of a donkey and a female onager.[149] Tell Brak remained an important commercial center during the Akkadian period,[150] and was one of Mitanni's main trade cities.[89] Many objects were manufactured in Mitannian Tell Brak, including furniture made of ivory, wood and bronze, in addition to glass.[92] The city provided evidence for the international commercial contacts of Mitanni, including Egyptian, Hittite and Mycenaean objects, some of which were produced in the region to satisfy the local taste.[92]

Equids

The Kungas of pre-Akkadian Nagar were used for drawing the carriages of kings before the domestication of the horse,[151] and a royal procession included up to fifty animals.[152] The kungas of Nagar were in great demand in the Eblaite empire;[148] they cost two kilos of silver, fifty times the price of a donkey,[151] and were imported regularly by the monarchs of Ebla to be used as transport animals and gifts for allied cities.[148] The horse was known in the region during the third millennium BC, but was not used as a draught animal before c. 18th century BC.[149]

Site

Excavations

Tell Brak was excavated by the British archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan, husband of Agatha Christie, in 1937 and 1938.[153] The Eye Temple was the first building unearthed and some artifacts from that initial excavation are now preserved in the British Museum's collection, including the famous Tell Brak Head.[94][154]

A team from the Institute of Archaeology of the University of London, led by David and Joan Oates, worked in the tell for 14 seasons between 1976 and 1993.[51] After 1993, excavations were conducted by a number of filed directors under the general guidance of David (until 2004) and Joan Oates.[51] Those directors included Roger Matthews (between 1994-1996), for the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research of the University of Cambridge; Geoff Emberling (between 1998-2002) and Helen McDonald (between 2000-2004), for the British Institute for the Study of Iraq and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[51] In 2006, Augusta McMahon became field director, also sponsored by the British Institute for the Study of Iraq.[51] A regional archaeological field survey in a 20 km (12 mi) radius around Brak was supervised by Henry T. Wright (between 2002–2005).[155] Many of the finds from the excavations at Tell Brak are on display in the Deir ez-Zor Museum.[156] The most recent excavations took place in the spring of 2011, but archaeological work is currently suspended due to the ongoing Syrian Civil War.[1]

Syrian Civil War

According to the Syrian authorities, the camp of archaeologists was looted, along with the tools and ceramics kept in it.[157] The site changed hands between the different combatants, mainly the Kurdish People's Protection Units and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.[158] In early 2015, Tell Brak was taken by the Kurdish forces after light fighting with the Islamic State.[159]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Patzens are large rectangular bricks that comes in different sizes.[9]

- ↑ The temple have multiple levels, the earliest two are named the red and grey levels respectively,[18] and they date to LC3.[19] The third level (the white level) is dated to period LC5 (c. 3200-3000 BC),[18][20] while the fourth and current visible one is named the "Latest Jemdet Nasr", and also dates to the late fourth millennium BC (LC5).[21] Excavations revealed two rebuilding following the "Latest Jemdet Nasr" building, and they date to the Early Dynastic period I.[21][22]

- ↑ Dated to the temple's grey level.[18]

- ↑ The temple is located in area TC, adjacent to the so called "Brak Oval" building.[30] It is dated to the Ninevite 5 period,[31] period J c. 2700 BC.[32] The temple consist of a single room with a mud brick altar,[31] and contained a cache of over 500 sealings.[33]

- ↑ Amar-An is the form of the name written in Sumerogram.[39] When read in Proto-Akkadian it reads Mara-Il.[40]

- ↑ The nature of the Akkadian early period is ambiguous, local texts do not reflect the reign of Sargon or his successors.[57] Two bowels bearing Rimush's inscription were discovered in the palace of his nephew Naram-Sin, however, they could have been diplomatic gifts to a local ruler.[58]

- ↑ Some scholars doubt that the Hurrian city of Nawar is identical with Nagar.[62] However, the consensus is that Nagar was known as "Nawar" for the Hurrians,[63] and written with that name as early as the Old Babylonian period.[64]

- ↑ Some of the building's bricks had Naram-Sin's name stamped on it.[69]

- ↑ Max Mallowan discovered a seal in 1947 and attributed it to Ur-Nammu of Ur; this led to the assumption that Ur controlled Tell-Brak.[78] However, the translation of the seal showed no sign of Ur-Nammu's name

- ↑ Harvey Weiss suggest the total abandonment of Nagar within fifty years following the Akkadians departure,[82] and attribute the event to a climatic disaster.[83] However, this view is controversial.[84]

- ↑ Previously, the Halafians were seen either as hill people who descended from the nearby mountains of southeastern Anatolia, or herdsmen from northern Iraq.[95] However, those views changed with the archaeology conducted by Peter Akkermans, which proved a continues indigenous origin of Halaf culture.[95]

- ↑ Belet is the feminine form of Bel, the east-Semitic title of a lord deity.[116] Belet-Nagar is translated as the lady of Nagar.[117]

- ↑ Belet-Nagar's worship was spread in wide areas, during year 8 of Amar-Sin's reign, a temple of Belet-Nagar was erected in Ur.[121]

- ↑ Geoff Emberling argues for a southern forced take-over instead of a peaceful interaction.[125]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Bowden, James (2012). "The Voices of Tell Brak". Archaeological Diggings. 19 (4): 48–51.

- ↑ Wayne A. Wiegand; Donald G. Jr. Davis (2015). Encyclopedia of Library History. p. 29.

- 1 2 Max Edgar Lucien Mallowan (1956). Twenty-five Years of Mesopotamian Discovery, 1932-1956. p. 24.

- ↑ British School of Archaeology in Iraq (1947). Iraq, Volume 9. p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Ur, Jason Alik; Oates, David; Karsgaard, Philip (2011). "The Spatial Dimensions of Early Mesopotamian Urbanism: The Tell Brak Suburban Survey, 2003-2006". British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 73: 1–19. doi:10.1017/s0021088900000061. ISSN 0021-0889.

- ↑ Donald M. Matthews (1997). The Early Glyptic of Tell Brak: Cylinder Seals of Third Millennium Syria. p. 129.

- ↑ John L. Brooke (2014). Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. p. 204.

- 1 2 Susan Pollock; Reinhard Bernbeck (2009). Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. p. 190.

- ↑ Peter Roger Stuart Moorey (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. p. 307.

- ↑ Douglas Northrop (2012). A Companion to World History. p. 167.

- 1 2 Oates, Joan (1987). "A Note on 'Ubaid and Mitanni Pottery from Tell Brak". Iraq. 49: 193–198. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200272.

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Glassner (2003). The Invention of Cuneiform: Writing in Sumer. p. 31.

- ↑ John L. Brooke (2014). Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. p. 209.

- ↑ Peter N. Peregrine; Melvin Ember (2003). Encyclopedia of Prehistory: Volume 8: South and Southwest Asia. p. 372.

- 1 2 Stephen Bertman (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. p. 31.

- ↑ Nancy H. Demand (2011). The Mediterranean Context of Early Greek History. p. 74.

- 1 2 Douglas P. Fry (2013). War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views. p. 220.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 199.

- ↑ Donald P. Hansen; Erica Ehrenberg (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. p. 152.

- 1 2 Lamia Al-Gailani Werr (2002). Of Pots and Plans: Papers on the Archaeology and History of Mesopatamia and Syria Presented to David Oates in Honour of His 75th Birthday. p. 87.

- 1 2 Lamia Al-Gailani Werr (2002). Of Pots and Plans: Papers on the Archaeology and History of Mesopatamia and Syria Presented to David Oates in Honour of His 75th Birthday. p. 84.

- ↑ Donald M. Matthews (1997). The Early Glyptic of Tell Brak: Cylinder Seals of Third Millennium Syria. p. 171.

- ↑ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 198.

- ↑ Donald P. Hansen; Erica Ehrenberg (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. p. 151.

- 1 2 3 Mark W. Chavalas; K. Lawson Younger, Jr. (2003). Mesopotamia and the Bible. p. 92.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 84.

- ↑ Maria Eugenia Aubet (2013). Commerce and Colonization in the Ancient Near East. p. 174.

- ↑ Nancy H. Demand (2011). The Mediterranean Context of Early Greek History. p. 83.

- 1 2 Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 200.

- ↑ Uniwersytet Warszawski Zakład Antropologii Historycznej (2009). "Short Fieldwork Report: Tell Brak (Syria), seasons 1984–2009. By Arkadiusz Sołtysiak". Bioarchaeology of the Near East. 3: 36. ISSN 1898-9403.

- 1 2 Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 216.

- ↑ Anne Porter (2012). Mobile Pastoralism and the Formation of Near Eastern Civilizations: Weaving Together Society. p. 186.

- ↑ Ur, Jason Alik (2010). "Cycles of Civilization in Northern Mesopotamia, 4400–2000 BC". Journal of Archaeological Research. 18: 411. doi:10.1007/s10814-010-9041-y. ISSN 1059-0161.

- 1 2 Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 217.

- 1 2 3 Erich Ebeling (2001). Nab - Nuzi. p. 75.

- 1 2 3 Emberling, Geoff; McDonald, Helen; Michael, Charles; Green, Walton A.; Hald, Mette Marie; Weber, Jill; Wright, Henry T. (2001). "Excavations at Tell Brak 2000: Preliminary report". British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 63: 21–54. doi:10.2307/4200500. ISSN 0021-0889.

- 1 2 3 David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: vol 2. Nagar in the third millennium BC. p. 99.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: vol 2. Nagar in the third millennium BC. p. 100.

- ↑ Marc Lebeau : Nabada (Tell Beydar), an Early Bronze Age City in the Syrian Jezirah, Lecture presented in Tübingen (10-2-2006). Page 18

- ↑ Pascal Butterlin (2006). Les Espaces Syro-Mésopotamiens: Dimensions de L'expérience Humaine au Proche-Orient ancien: Volume D'hommage Offert à Jean-Claude Margueron (in French). p. 121.

- 1 2 3 4 5 David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: vol 2. Nagar in the third millennium BC. p. 101.

- ↑ Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 84.

- ↑ Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 82.

- ↑ Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 66.

- 1 2 Edward Lipiński (2001). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar. p. 52.

- ↑ "War of the lords. The battle of chronology - page.5". Joachim Bretschneider, Anne-Sophie Van Vyve, Greta Jans Leuven. 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Amanda H. Podany (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. p. 57.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 208.

- ↑ Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum; Nicole Brisch; Jesper Eidem (2014). Constituent, Confederate, and Conquered Space: The Emergence of the Mittani State. p. 103.

- ↑ Amanda H. Podany (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. p. 135.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 877.

- 1 2 3 Joan Oates (2005). Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 131, 2004 Lectures. p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Joan Oates (2005). Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 131, 2004 Lectures. p. 10.

- 1 2 Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 228.

- 1 2 Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 163.

- 1 2 3 Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 469.

- ↑ Donald M. Matthews (1997). The Early Glyptic of Tell Brak: Cylinder Seals of Third Millennium Syria. p. 2.

- 1 2 Joan Oates (2005). Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 131, 2004 Lectures. p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 162.

- 1 2 Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 752.

- ↑ Joan Goodnick Westenholz (1997). Legends of the Kings of Akkade: The Texts. p. 244.

- ↑ David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: vol 2. Nagar in the third millennium BC. p. 39.

- 1 2 David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: vol 2. Nagar in the third millennium BC. p. 143.

- ↑ Michael Hudson, Baruch A. Levine (1999). Urbanization and Land Ownership in the Ancient Near East: A Colloquium Held at New York University, November 1996, and the Oriental Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia, May 1997. p. 240.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. p. 21.

- ↑ Margreet L. Steiner; Ann E. Killebrew (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE. p. 398.

- 1 2 Alexander J. de Voogt; Irving L. Finkel (2010). The Idea of Writing: Play and Complexity. p. 117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arne Wossink (2009). Challenging Climate Change: Competition and Cooperation Among Pastoralists and Agriculturalists in Northern Mesopotamia (c. 3000-1600 BC). p. 30.

- ↑ David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (1997). Excavations at Tell Brak, Volume 1. p. 109.

- ↑ Donald P. Hansen; Erica Ehrenberg (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. p. 146.

- ↑ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 279.

- ↑ Joachim Bretschneider; Jan Driessen; Karel van Lerberghe (2007). Power and Architecture: Monumental Public Architecture in the Bronze Age Near East and Aegean. p. 171.

- ↑ David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: vol 2. Nagar in the third millennium BC. p. 170.

- ↑ David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (1997). Excavations at Tell Brak, Volume 1. p. 141.

- ↑ David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: vol 2. Nagar in the third millennium BC. p. 102.

- ↑ Arne Wossink (2009). Challenging Climate Change: Competition and Cooperation Among Pastoralists and Agriculturalists in Northern Mesopotamia (c. 3000-1600 BC). p. 31.

- ↑ David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: Nagar in the third millennium BC Vol. 2. p. 109.

- ↑ Weiss, Harvey (1983). "Excavations at Tell Leilan and the Origins of North Mesopotamian cities in the Third Millennium B.C.". Paléorient. 9 (2): 49. ISSN 0153-9345.

- ↑ Charlotte Trümpler (2001). Agatha Christie and Archaeology. p. 129.

- 1 2 Margreet L. Steiner; Ann E. Killebrew (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE. p. 372.

- ↑ Harvey Weiss (2012). Seven Generations Since the Fall of Akkad. p. 5.

- ↑ Harvey Weiss (2012). Seven Generations Since the Fall of Akkad. p. 11.

- ↑ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 283.

- 1 2 Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 226.

- 1 2 Erich Ebeling (2001). Nab - Nuzi. p. 76.

- 1 2 3 Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. p. 492.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. p. 493.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Elena Efimovna Kuzʹmina (2007). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. p. 133.

- ↑ Charles Burney (2004). Historical Dictionary of the Hittites. p. 131.

- ↑ Marian H. Feldman (2006). Diplomacy by Design: Luxury Arts and an "International Style" in the Ancient Near East, 1400-1200 BCE. p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Joan Aruz; Kim Benzel; Jean M. Evans (2008). Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. p. 195.

- ↑ David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (1997). Excavations at Tell Brak, Volume 1. p. 14.

- 1 2 "Alabaster head". British Museum. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- 1 2 Maria Grazia Masetti-Rouault; Olivier Rouault; M. Wafler (2000). La Djéziré et l'Euphrate syriens de la protohistoire à la fin du second millénaire av. J.C, Tendances dans l'interprétation historique des données nouvelles, (Subartu) - Chapter : Old and New Perspectives on the Origins of the Halaf Culture by Peter Akkermans. pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). p. 116.

- 1 2 3 4 Justin Jennings (2010). Globalizations and the Ancient World. p. 73.

- ↑ Charles, Michael; Pessin, Hugues; Hald, Mette Marie (2010). "Tolerating change at Late Chalcolithic Tell Brak: responses of an early urban society to an uncertain climate". Environmental Archaeology : The Journal of Human Palaeoecology. 15 (2): 184. ISSN 1461-4103.

- ↑ D. T. Potts (2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. p. 429.

- 1 2 3 Catherine Kuzucuoğlu; Catherine Marro (2007). Sociétés humaines et changement climatique à la fin du troisième millénaire: une crise a-t-elle eu lieu en haute Mésopotamie? : actes du colloque de Lyon, 5-8 décembre 2005. p. 433.

- ↑ Keith Brown; Sarah Ogilvie (2010). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. p. 313.

- ↑ Hans Gustav Güterbock; K. Aslihan Yener; Harry A. Hoffner; Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History: Papers in Memory of Hans G. Güterbock. p. 22.

- 1 2 Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum; Nicole Brisch; Jesper Eidem (2014). Constituent, Confederate, and Conquered Space: The Emergence of the Mittani State. p. 100.

- ↑ D. T. Potts (2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. p. 570.

- 1 2 3 Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum; Nicole Brisch; Jesper Eidem (2014). Constituent, Confederate, and Conquered Space: The Emergence of the Mittani State. p. 152.

- ↑ Glenn A. Carnagey; Glenn Carnagey; Keith N. Schoville (2005). Beyond the Jordan: Studies in Honor of W. Harold Mare. p. 121.

- ↑ Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum; Nicole Brisch; Jesper Eidem (2014). Constituent, Confederate, and Conquered Space: The Emergence of the Mittani State. p. 153.

- ↑ Dominique Charpin (2010). Reading and Writing in Babylon. p. 49.

- ↑ Roger D. Woodard (2008). The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. p. 82.

- ↑ Abdul Jalil Jawad (1965). The Advent of the Era of Townships in Northern Mesopotamia. p. 73.

- ↑ Rivka Ulmer (2009). Egyptian Cultural Icons in Midrash, Volume 23. p. 286.

- ↑ Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 76.

- ↑ Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 90.

- 1 2 Lamia Al-Gailani Werr (2002). Of Pots and Plans: Papers on the Archaeology and History of Mesopatamia and Syria Presented to David Oates in Honour of His 75th Birthday. p. 85.

- ↑ Abdul Jalil Jawad (1965). The Advent of the Era of Townships in Northern Mesopotamia. p. 50.

- ↑ Stephen Bertman (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. p. 117.

- ↑ David Oates; Joan Oates; Helen McDonald (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak: Nagar in the third millennium BC Vol. 2. p. 381.

- ↑ Luca Peyronel (2006). Orientalia Vol. 75. p. 398.

- ↑ Douglas B. Miller; R. Mark Shipp (1996). An Akkadian Handbook: Paradigms, Helps, Glossary, Logograms, and Sign List. p. 66.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter (2002). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 86.

- ↑ Hans Gustav Güterbock; K. Aslihan Yener; Harry A. Hoffner; Simrit Dhesi (2002). Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History: Papers in Memory of Hans G. Güterbock. p. 29.

- ↑ Elizabeth F. Henrickson; Ingolf Thuesen; I. Thuesen (1989). Upon this Foundation: The N̜baid Reconsidered : Proceedings from the U̜baid Symposium, Elsinore, May 30th-June 1st 1988. p. 346.

- ↑ Joachim Bretschneider; Jan Driessen; Karel van Lerberghe (2007). Power and Architecture: Monumental Public Architecture in the Bronze Age Near East and Aegean. p. 162.

- ↑ Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 19.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (2013). The Sumerian World. p. 84.

- ↑ Anne Porter (2012). Mobile Pastoralism and the Formation of Near Eastern Civilizations: Weaving Together Society. p. 140.

- ↑ Anne Porter (2012). Mobile Pastoralism and the Formation of Near Eastern Civilizations: Weaving Together Society. p. 141.

- ↑ Luca Peyronel (2006). Orientalia Vol. 75. p. 408.

- ↑ Donald M. Matthews (1997). The Early Glyptic of Tell Brak: Cylinder Seals of Third Millennium Syria. p. 136.

- ↑ D. T. Potts (2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. p. 655.

- 1 2 Luca Peyronel (2006). Orientalia Vol. 75. p. 400.

- 1 2 Luca Peyronel (2006). Orientalia Vol. 75. p. 402.

- 1 2 David W. Anthony (2010). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. p. 403.

- ↑ Peter Fibiger Bang; Walter Scheidel (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the State in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean. p. 101.

- 1 2 Norman Yoffee (2015). The Cambridge World History, Volume 3. p. 262.

- 1 2 James E. Snead; Clark L. Erickson; J. Andrew Darling (2011). Landscapes of Movement: Trails, Paths, and Roads in Anthropological Perspective. p. 201.

- ↑ Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 65.

- ↑ Lauren Ristvet (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 61.

- ↑ André J. Veldmeijer; Alima Ikram (2013). Chasing Chariots: Proceedings of the first international chariot conference (Cairo 2012). p. 184.

- ↑ Joan Oates (2005). Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 131, 2004 Lectures. p. 13.

- ↑ William J. Hamblin (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. p. 304.

- ↑ Jørgen Læssøe (2014). People of Ancient Assyria: Their Inscriptions and Correspondence. p. 79.

- ↑ Donald M. Matthews (1997). The Early Glyptic of Tell Brak: Cylinder Seals of Third Millennium Syria. p. 191.

- ↑ Dominik Bonatz (2014). The Archaeology of Political Spaces: The Upper Mesopotamian Piedmont in the Second Millennium BCE. p. 73.

- ↑ Douglas P. Fry (2013). War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views. p. 219.

- 1 2 Jane McIntosh (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives. p. 254.

- ↑ Justin Jennings (2010). Globalizations and the Ancient World. p. 72.

- 1 2 3 Paolo Matthiae; Nicoló Marchetti (2013). Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 436.

- 1 2 3 Elena Efimovna Kuzʹmina (2007). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. p. 134.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 232.

- 1 2 Joan Oates (2005). Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 131, 2004 Lectures. p. 6.

- ↑ James E. Snead; Clark L. Erickson; J. Andrew Darling (2011). Landscapes of Movement: Trails, Paths, and Roads in Anthropological Perspective. p. 200.

- ↑ Mallowan, M.E.L. (1947). "Excavations at Brak and Chagar Bazar". Iraq. 9: 1–259. doi:10.2307/4199532. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4199532. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ "Tell-Brak". British Museum. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Tell-Brak, History of Excavation". McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Dominik Bonatz; Hartmut Kühne; Asʻad Mahmoud; Matḥaf Dayr al-Zawr (1998). Rivers and steppes: cultural heritage and environment of the Syrian Jezireh : catalogue to the Museum of Deir ez-Zor. p. 73.

- ↑ "Monuments Men: The Quest to Save Syria's History". Spiegel. 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Syrian Kurds take town from Islamists: watchdog". Reuters. 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Volunteering with the Kurds to fight IS". BBC. 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79666-8.

- Al-Gailani Werr, Lamia (2002). Of Pots and Plans: Papers on the Archaeology and History of Mesopatamia and Syria Presented to David Oates in Honour of His 75th Birthday. Nabu Publications. ISBN 978-1-897-75062-9.

- Aruz, Joan; Benzel, Kim; Evans, Jean M. (2008). Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-588-39295-4.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-15908-6.

- Crawford, Harriet (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-21912-2.

- Matthews, Donald M (1997). The Early Glyptic of Tell Brak: Cylinder Seals of Third Millennium Syria. Saint-Paul. ISBN 978-3-525-53896-8.

- Matthews, Roger; Matthews, Wendy (2003). Excavations at Tell Brak Vol. IV: Exploring a Regional Centre in Upper Mesopotamia, 1994-1996. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. ISBN 978-1-902-93716-8.

- Oates, David; Oates, Joan; McDonald, Helen (1997). Excavations at Tell Brak, Vol. I: The Mitanni and Old Babylonian Periods. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. ISBN 978-0-951-94205-5.

- Oates, David; Oates, Joan; McDonald, Helen (2001). Excavations at Tell Brak, Vol II: Nagar in The Third Millennium BC. British School of Archaeology in Iraq. ISBN 978-0-951-94209-3.

- Oates, Joan (2005). Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 131, 2004 Lectures. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-197-26351-8.

- Ristvet, Lauren (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06521-5.

- Steiner, Margreet; Killebrew, Ann (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000-332 BCE. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-191-66255-3.

- Wossink, Arne (2009). Challenging Climate Change: Competition and Cooperation Among Pastoralists and Agriculturalists in Northern Mesopotamia (c. 3000-1600 BC). Sidestone Press. ISBN 978-9-088-90031-0.

Further reading

- Matthews, Donald; Eidem, Jesper (1993). "Tell Brak and Nagar". Iraq. 55: 201–207. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200376.

- Oates, David; Oates, Joan (1989). "Akkadian Buildings at Tell Brak". Iraq. 51: 193–211. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200303.

- Oates, Joan (1982). "Some Late Early Dynastic III Pottery from Tell Brak". Iraq. 44 (2): 205–219. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200163.

- Joan Oates, Joan; McMahon, Augusta; Karsgaard, Philip; Al Quntar, Salam; Ur, Jason (2007). "Early Mesopotamian urbanism: a new view from the north". Antiquity. 81 (313): 585–600. ISSN 0003-598X.

- Wilhelm, G. (1991). "A Hurrian Letter from Tell Brak". Iraq. 53: 159–168. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200345.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tell Brak. |

- Tell Brak feature

- Piotr Michalowski, "Bibliographical information (Tell Brak & related matters)

- Piotr Michalowski, "An Early Dynastic Tablet of ED Lu A from Tell Brak (Nagar)" (pdf file)

- SciAm: Ancient Squatters May Have Been the World's First Suburbanites

- Death and the City: Recent Work at Tell Brak, Syra - Oriental Institute video/audio lecture