Neocolonialism

Neocolonialism, neo-colonialism or neo-imperialism is the practice of using capitalism, globalization and cultural imperialism to influence a developing country in lieu of direct military control (imperialism) or indirect political control (hegemony). Neo-colonialism is discussed in the works of Jean-Paul Sartre (Colonialism and Neo-colonialism, 1964)[1] and Noam Chomsky (The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism, 1979).[2]

Term

Origins

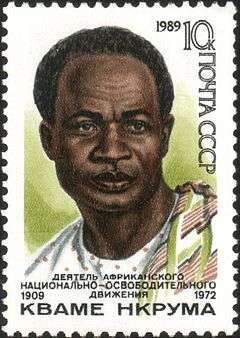

Neocolonialism labels European countries' continued economic and cultural relationships with their former colonies, African countries that had been liberated in the aftermath of Second World War. Kwame Nkrumah, former president of Ghana (1960–66), coined the term, which appeared in the 1963 preamble of the Organization of African Unity Charter, and was the title of his 1965 book Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism (1965).[3] Nkrumah theoretically developed and extended to the post–War 20th century the socio-economic and political arguments presented by Lenin in the pamphlet Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917). The pamphlet frames 19th-century imperialism as the logical extension of geopolitical power, to meet the financial investment needs of the political economy of capitalism.[4] In Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism, Kwame Nkrumah wrote:

In place of colonialism, as the main instrument of imperialism, we have today neo-colonialism . . . [which] like colonialism, is an attempt to export the social conflicts of the capitalist countries. . . .

The result of neo-colonialism is that foreign capital is used for the exploitation rather than for the development of the less developed parts of the world. Investment, under neo-colonialism, increases, rather than decreases, the gap between the rich and the poor countries of the world. The struggle against neo-colonialism is not aimed at excluding the capital of the developed world from operating in less developed countries. It is aimed at preventing the financial power of the developed countries being used in such a way as to impoverish the less developed.[5]

The non-aligned world

Neocolonialism was used to describe a type of foreign intervention in countries belonging to the Pan-Africanist movement, as well as the Bandung Conference (Asian–African Conference, 1955), which led to the Non-Aligned Movement (1961). Neocolonialism was formally defined by the All-African Peoples' Conference (AAPC) and published in the Resolution on Neo-colonialism. At both the Tunis conference (1960) and the Cairo conference (1961), AAPC described the actions of the French Community of independent states, organized by France, as neocolonial.[6]

Throughout the decades of the Cold War, the countries of the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America defined neocolonialism as the primary, collective enemy of the economies and cultures of their respective countries. Moreover, neocolonialism was integrated into the national liberation ideologies of Marxist guerrilla armies. During the 1970s, in the Portuguese African colonies of Mozambique and Angola, upon assuming government power, the Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO, Frente de Libertação de Moçambique), and the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola — Labour Party (MPLA, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola — Partido do Trabalho), respectively, established policies to counter neocolonial agreements with the (former) colonist country.

Françafrique

The representative example of European neocolonialism is Françafrique, the "French Africa" constituted by the continued close relationships between France and its former African colonies. In 1955, the initial usage of the "French Africa" term, by President Félix Houphouët-Boigny of Ivory Coast, denoted positive social, cultural and economic Franco–African relations. It was later applied by neocolonialism critics to describe an imbalanced international relation. The politician Jacques Foccart, the principal advisor for African matters to French presidents Charles de Gaulle (1958–69) and Georges Pompidou (1969–1974), was the principal proponent of Françafrique.[7] The works of Verschave and Beti reported a forty-year, post-independence relationship with France's former colonial peoples, which featured colonial garrisons in situ and monopolies by French multinational corporations, usually for the exploitation of mineral resources. It was argued that the African leaders with close ties to France — especially during the Soviet–American Cold War (1945–91) — acted more as agents of French business and geopolitical interests, than as the national leaders of sovereign states. Cited examples are Omar Bongo (Gabon), Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Ivory Coast), Gnassingbé Eyadéma (Togo), Denis Sassou-Nguesso (Republic of the Congo), Idriss Déby (Chad), and Hamani Diori (Niger).

- Francophonie

The French Community (1958–95) and the seventy-five-country Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (International Francophone Organisation) have been criticized as agents of French neocolonial African influence, especially by promoting the French language; however, in 1966, Algerian intellectual Kateb Yacine said:

La Francophonie might be a neo-colonial political machine, which only perpetuates our alienation, but the usage of the French language does not mean that one is an agent of a foreign power; and I write in French to tell the French that I am not French.

Belgian Congo

After the decolonization of Belgian Congo, Belgium continued to control, through the Société Générale de Belgique, an estimated 70% of the Congolese economy following the decolonization process. The most contested part was in the province of Katanga where the Union Minière du Haut Katanga, part of the Société, controlled the mineral-resource-rich province. After a failed attempt to nationalize the mining industry in the 1960s, it was reopened to foreign investment.

Neocolonial economic dominance

In 1961, regarding the economic mechanism of neocolonial control, in the speech Cuba: Historical Exception or Vanguard in the Anti-colonial Struggle?, Argentine revolutionary Ché Guevara said:

We, politely referred to as "underdeveloped", in truth, are colonial, semi-colonial or dependent countries. We are countries whose economies have been distorted by imperialism, which has abnormally developed those branches of industry or agriculture needed to complement its complex economy. "Underdevelopment", or distorted development, brings a dangerous specialization in raw materials, inherent in which is the threat of hunger for all our peoples. We, the "underdeveloped", are also those with the single crop, the single product, the single market. A single product whose uncertain sale depends on a single market imposing and fixing conditions. That is the great formula for imperialist economic domination.[10]

Dependency theory

Dependency theory is the theoretical description of economic neocolonialism. It proposes that the global economic system comprises wealthy countries at the center, and poor countries at the periphery. Economic neocolonialism extracts the human and natural resources of a poor country to flow to the economies of the wealthy countries. It claims that the poverty of the peripheral countries is the result of how they are integrated in the global economic system. Dependency theory derives from the Marxist analysis of economic inequalities within the world's system of economies, thus, under-development of the periphery is a direct result of development in the center. It includes the concept of the late 19th century semi-colony.[11] It contrasts the Marxist perspective of the Theory of Colonial Dependency with capitalist economics. The latter proposes that poverty is a development stage in the poor country's progress towards full integration in the global economic system. Proponents of Dependency Theory, such as Venezuelan historian Federico Brito Figueroa, who investigated the socioeconomic bases of neocolonial dependency, influenced the thinking of the former President of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez.

The Cold War

During the mid-to-late 20th century, in the course of the ideological conflict between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., each country and its satellite states accused each other of practising neocolonialism in their imperial and hegemonic pursuits.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18] The struggle included proxy wars, fought by client states in the decolonised countries. Cuba, the Warsaw Pact bloc, Egypt under Gamal Abdel Nasser (1956–70), et al. accused the U.S. of sponsoring anti-democratic governments whose régimes did not represent the interests of their people and of overthrowing elected governments (African, Asian, Latin American) that did not support U.S. geopolitical interests.

In the 1960s, under the leadership of Chairman Mehdi Ben Barka, the Cuban Tricontinental Conference (Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America) recognised and supported the validity of revolutionary anti-colonialism as a means for colonised peoples of the Third World to achieve self-determination, which policy angered the U.S. and France. Moreover, Chairman Barka headed the Commission on Neocolonialism, which dealt with the work to resolve the neocolonial involvement of colonial powers in decolonised counties; and said that the U.S., as the leading capitalist country of the world, was, in practise, the principal neocolonialist political actor.

Multinational corporations

Critics of neocolonialism also argue that investment by multinational corporations enriches few in underdeveloped countries and causes humanitarian, environmental and ecological damage to their populations. They argue that this results in unsustainable development and perpetual underdevelopment. These countries remain reservoirs of cheap labor and raw materials, while restricting access to advanced production techniques to develop their own economies. In some countries, privatization of natural resources, while initially leading to an influx of investment, is often followed by increases in unemployment, poverty and a decline in per-capita income.[19]

In the West African nations of Guinea-Bissau, Senegal and Mauritania, fishing was historically central to the economy. Beginning in 1979, the European Union began negotiating contracts with governments for fisheries off the coast of West Africa. Commercial, unsustainable, over-fishing by foreign fleets played a significant role in large-scale unemployment and migration of people across the region.[20] This violates the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas, which recognizes the importance of fishing to local communities and insists that government fishing agreements with foreign companies should target only surplus stocks.[21]

International borrowing

To alleviate the effects of neocolonialism, American economist Jeffrey Sachs recommended that the entire African debt (ca. 200 billion U.S. dollars) be dismissed, and recommended that African nations not repay the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF):[22]

The time has come to end this charade. The debts are unaffordable. If they won't cancel the debts, I would suggest obstruction; you do it, yourselves. Africa should say: "Thank you very much, but we need this money to meet the needs of children who are dying, right now, so, we will put the debt-servicing payments into urgent social investment in health, education, drinking water, the control of AIDS, and other needs".

Sino–African relations

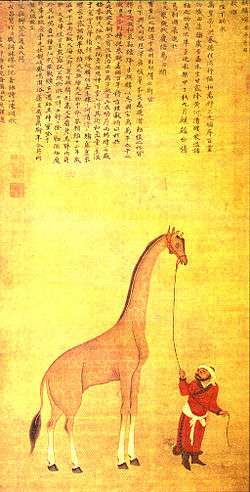

Historically, China and Somalia had strong trade ties. Giraffes, zebras and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between Asia and Africa.[23] The People's Republic of China has built increasingly strong ties with African nations,[24][25] becoming Africa's largest trading partner.[26][27] As of August 2007, an estimated 750,000 Chinese nationals were working or living for extended periods in Africa.[28][29] China is purchasing natural resources — petroleum and minerals — to fuel the Chinese economy and to finance international business enterprises.[30][31] In 2006, two-way trade had increased to $50 billion.[32]

Not all dealings have involved direct monetary exchanges. In 2007, China and Democratic Republic of the Congo entered into an agreement whereby Chinese state-owned firms would provide various services (infrastructure projects) in exchange for an equivalent amount of Congolese copper.[33]

According to China's critics, China offered Sudan support by threatening to use its U.N. Security Council veto to protect Sudan from sanctions and was able to water down every resolution on Darfur in order to protect its interests.[34]

South Korea's land acquisitions

To ensure a reliable, long-term supply of food, the South Korean government and powerful Korean multinationals bought farming rights to millions of hectares of agricultural land in under-developed countries.[35]

South Korea's RG Energy Resources Asset Management CEO Park Yong-soo stressed that "the nation does not produce a single drop of crude oil and other key industrial minerals. To power economic growth and support people's livelihoods, we cannot emphasize too much that securing natural resources in foreign countries is a must for our future survival."[36] The head of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Jacques Diouf, stated that the rise in land deals could create a form of " neocolonialism", with poor states producing food for the rich at the expense of their own hungry people.

In 2008, South Korean multinational Daewoo Logistics secured 1.3 million hectares of farmland in Madagascar to grow maize and crops for biofuels. Roughly half of the country's arable land, as well as rainforests were to be converted into palm and corn monocultures, producing food for export from a country where a third of the population and 50 percent of children under 5 are malnourished, using South African workers instead of locals. Local residents were not consulted or informed, despite being dependent on the land for food and income. The controversial deal played a major part in prolonged anti-government protests that resulted in over a hundred deaths.[35] This was a source of popular resentment that contributed to the fall of then-President Marc Ravalomanana. The new president, Andry Rajoelina, cancelled the deal.[37] Tanzania later announced that South Korea was in talks to develop 100,000 hectares for food production and processing for 700 to 800 billion won. Scheduled to be completed in 2010, it was to be the largest single piece of overseas South Korean agricultural infrastructure ever built.[35]

In 2009, Hyundai Heavy Industries acquired a majority stake in a company cultivating 10,000 hectares of farmland in the Russian Far East and a South Korean provincial government secured 95,000 hectares of farmland in Oriental Mindoro, central Philippines, to grow corn. The South Jeolla province became the first provincial government to benefit from a new central government fund to develop farmland overseas, receiving a loan of $1.9 million. The project was expected to produce 10,000 tonnes of feed in the first year.[38] South Korean multinationals and provincial governments purchased land in Sulawesi, Indonesia, Cambodia and Bulgan, Mongolia. The national South Korean government announced its intention to invest 30 billion won in land in Paraguay and Uruguay. As of 2009 discussions with Laos, Myanmar and Senegal were underway.[35]

Other approaches

Although the concept of neocolonialism was originally developed within a Marxist theoretical framework and is generally employed by the political left, the term " neocolonialism" is found in other theoretical frameworks.

Coloniality

"Coloniality" claims that knowledge production is strongly influenced by the context of the person producing the knowledge and that this has further disadvantaged developing countries with limited knowledge production infrastructure. It originated among critics of subaltern theories, which, although strongly de-colonial, are less concerned with the source of knowledge.[39]

Cultural theory

One variant of neocolonialism theory critiques cultural colonialism, the desire of wealthy nations to control other nations' values and perceptions through cultural means such as media, language, education and religion, ultimately for economic reasons. One impact of this is "colonial mentality", feelings of inferiority that lead post-colonial societies to latch onto physical and cultural differences between the foreigners and themselves. Foreign ways become held in higher esteem than indigenous ways. Given that colonists and colonizers were generally of different races, the colonised may over time hold that the colonisers' race was responsible for their superiority. Rejections of the colonizers culture, such as the Negritude movement, have been employed to overcome these associations. Post-colonial importation or continuation of cultural mores or elements may be regarded as a form of neocolonialism.

Postcolonialism

Post-colonialism theories in philosophy, political science, literature and film deal with the cultural legacy of colonial rule. Post-colonialism studies examine how once-colonised writers articulate their national identity; how knowledge about the colonised was generated and applied in service to the interests of the colonizer; and how colonialist literature justified colonialism by presenting the colonised people as inferior whose society, culture and economy must be managed for them. Post-colonial studies incorporate subaltern studies of "history from below"; post-colonial cultural evolution; the psychopathology of colonization (by Frantz Fanon); and the cinema of film makers such as the Cuban Third Cinema, e.g. Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, and Kidlat Tahimik.

Critical theory

Critiques of postcolonialism/neocolonialism are evident in literary theory. International relations theory defined "postcolonialism" as a field of study. While the lasting effects of cultural colonialism are of central interest The intellectual antecedents in cultural critiques of neocolonialism are economic. Critical international relations theory references neocolonialism from Marxist positions as well as postpositivist positions, including postmodernist, postcolonial and feminist approaches. These differ from both realism and liberalism in their epistemological and ontological premises. The neo-liberalist approach tends to depict modern forms of colonialism as a Benevolent imperialism.

Conservation and neocolonialism

Wallerstein and separately Frank claim that the modern conservation movement, as practiced by international organizations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature, inadvertently developed a neocolonial relationship with underdeveloped nations.[40]

See also

- Academic imperialism

- Americanization

- Colonialism

- Cultural hegemony

- Cultural imperialism

- Dependency theory

- Ecological imperialism

- François-Xavier Verschave's book on Françafrique

- Gatekeeper state: the concept of neocolonial "successor states," introduced by the African historian Frederick Cooper in Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present.

- Global apartheid

- Hegemony

- Impact of Western European colonialism and colonisation

- Imperialism

- List of coups d'état and coup attempts

- Modernization theory

- Neoliberalism

- New imperialism

- Oil imperialism

- Post-colonialism

- Sino-African relations

- Trans-Pacific Partnership

- Washington Consensus

References

- ↑ Sartre, Jean-Paul (2001). Colonialism and Neocolonialism. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-19146-3.

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam; Herman, Edward S. (1979). The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism. Black Rose Books Ltd. p. 42ff. ISBN 978-0-919618-88-6.

- ↑ Arnold, Guy (6 April 2010). The A to Z of the Non-Aligned Movement and Third World. Scarecrow Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-4616-7231-9.

- ↑ Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism Archived October 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.. transcribed from Lenin's Selected Works, Progress Publishers, 1963, Moscow, Volume 1, pp. 667–766.

- ↑ From the Introduction. Kwame Nkrumah. Neo-Colonialism, The Last Stage of Imperialism. First Published: Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd., London (1965). Published in the USA by International Publishers Co., Inc., (1966);

- ↑ Wallerstein, p. 52: 'It attempted the one serious, collectively agreed-upon definition of neo-colonialism, the key concept in the armory of the revolutionary core of the movement for African unity'; and William D. Graf's review of Neo-colonialism and African Politics: a Survey of the Impact of Neo-colonialism on African Political Behaviour (1980, Yolamu R. Barongo, in the Canadian Journal of African Studies, p. 601: 'The term, itself, originated in Africa, probably with Nkrumah, and received collective recognition at the 1961 All-African People's Conference.'

- ↑ Kaye Whiteman, "The Man Who Ran Françafrique — French Politician Jacques Foccart's Role in France's Colonization of Africa Under the Leadership of Charles de Gaulle", obituary in The National Interest, Fall 1997.

- ↑ (Quote by Kateb Yacine in French)

- ↑ Kateb Yacine bio (Quote in French)

- ↑ "Cuba: Historical exception or vanguard in the anticolonial struggle?" speech by Che Guevara on 9 April 1961

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, "Semicolonial Countries and Semi-Industrialised Dependent Countries", New International (New York), No.5, pp.149-175

- ↑ Kanet, Roger E.; Miner, Deborah N.; Resler, Tamara J. (2 April 1992). Soviet Foreign Policy in Transition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-521-41365-7.

- ↑ Ruether, Rosemary Radford (2008). Christianity and Social Systems: Historical Constructions and Ethical Challenges. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7425-4643-1.

Neo-colonialism means that European powers and the United States no longer rule dependent territories, directly through their occupying troops and imperial bureaucracy. Rather, they control the area's resources indirectly, through business corporations and the financial lending institutions they dominate ...

- ↑ Siddiqi, Yumna (2008). Anxieties of Empire and the Fiction of Intrigue. Columbia University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-231-13808-6. provides the standard definition of "Neo-colonialism" specific to the US and European colonialism.

- ↑ Shannon, Thomas R. (1996). An Introduction to the World-system Perspective. Westview Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-8133-2452-4., wherein "Neo-colonialism" is defined as a capitalist phenomenon.

- ↑ Blanchard, William H. (1996). Neocolonialism American Style, 1960-2000. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 3–12, defines "Neo–colonialism" in page 7. ISBN 978-0-313-30013-4.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, Hugh (1977). Nations and States: An Enquiry Into the Origins of Nations and the Politics of Nationalism. Methuen. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-416-76810-7. Provides the history of the word "neo-colonialism" as an anti-capitalist term (p. 339_ also applicable to the U.S.S.R. (p. 322).

- ↑ Edward M. Bennett. "Colonialism and Neo-colonialism" (pp. 285–291) in Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy. Alexander DeConde, Richard Dean Burns, Fredrik Logevall eds. Second Edition. Simon and Schuster, (2002) ISBN 0-684-80657-6. Clarifies that neo-colonialism is a practice of the colonial powers, that "the Soviets practiced imperialism, not colonialism".

- ↑ "World Bank, IMF Threw Colombia Into Tailspin" Archived September 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. The Baltimore Sun, April 4, 2002

- ↑ "Europe Takes Africa's Fish, and Boatloads of Migrants Follow" Archived September 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times, January 14, 2008

- ↑ United Nations 2007

- ↑ "Africa 'should not pay its debts'". BBC News. 6 July 2004. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ↑ East Africa and its Invaders pg.37

- ↑ Online, Asia Time. "Asia Times Online :: China News - Military backs China's Africa adventure".

- ↑ "Mbeki warns on China-Africa ties". 14 December 2006 – via bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "China becomes Africa´s largest trading partner CCTV News - CNTV English".

- ↑ "China overtakes US as Africa's top trading partner".

- ↑ "Breaking News, World News & Multimedia".

- ↑ "Chinese imperialism in Africa - International Communist Current".

- ↑ "China in Africa".

- ↑ Is China Africa's new imperialist power?

- ↑ "Is China the new colonial power in Africa?" Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Taipei Times, November 1, 2006

- ↑ China's Quest for Resources - A ravenous dragon Archived November 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. The Economist, March 13, 2008

- ↑ "The Increasing Importance of African Oil". Power and Interest News Report. 2007-03-20.

- 1 2 3 4 "Korea's Overseas Development Backfires". 4 December 2009.

- ↑ Coherent State Support Key to Overseas Resources Development Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Korea Times.

- ↑ Madagascar scraps Daewoo farm deal Financial Times.

- ↑ S. Korea Leases Philippine Farmland to Grow Corn Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Korea Times.

- ↑ Grosfoguel, Ramon (3 April 2007). "The Epistemic Decolonial Turn". Cultural Studies.

- ↑ In a manner consistent with Immanuel Wallerstein's World Systems Theory (Wallerstein, 1974) and Andre Gunder Frank's Dependency Theory (Frank, 1975).

Further reading

- Opoku Agyeman. Nkrumah's Ghana and East Africa: Pan-Africanism and African interstate relations (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1992).

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Global communication without universal civilization. INU societal research. Vol.1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations : Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Bill Ashcroft (ed., et al.) The post-colonial studies reader (Routledge, London, 1995).

- Yolamu R Barongo. neo-colonialism and African politics: A survey of the impact of neo-colonialism on African political behavior (Vantage Press, NY, 1980).

- Mongo Beti, Main basse sur le Cameroun. Autopsie d'une décolonisation (1972), new edition La Découverte, Paris 2003 [A classical critique of neo-colonialism. Raymond Marcellin, the French Minister of the Interior at the time, tried to prohibit the book. It could only be published after fierce legal battles.]

- Frédéric Turpin. De Gaulle, Pompidou et l'Afrique (1958-1974): décoloniser et coopérer (Les Indes savantes, Paris, 2010. [Grounded on Foccart's previously inaccessibles archives]

- Kum-Kum Bhavnani. (ed., et al.) Feminist futures: Re-imagining women, culture and development (Zed Books, NY, 2003). See: Ming-yan Lai's "Of Rural Mothers, Urban Whores and Working Daughters: Women and the Critique of Neocolonial Development in Taiwan's Nativist Literature," pp. 209–225.

- David Birmingham. The decolonization of Africa (Ohio University Press, 1995).

- Charles Cantalupo(ed.). The world of Ngugi wa Thiong'o (Africa World Press, 1995).

- Laura Chrisman and Benita Parry (ed.) Postcolonial theory and criticism (English Association, Cambridge, 2000).

- Renato Constantino. Neocolonial identity and counter-consciousness: Essays on cultural decolonization (Merlin Press, London, 1978).

- George A. W. Conway. A responsible complicity: Neo/colonial power-knowledge and the work of Foucault, Said, Spivak (University of Western Ontario Press, 1996).

- Julia V. Emberley. Thresholds of difference: feminist critique, native women's writings, postcolonial theory (University of Toronto Press, 1993).

- Nikolai Aleksandrovich Ermolov. Trojan horse of neo-colonialism: U.S. policy of training specialists for developing countries (Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1966).

- Thomas Gladwin. Slaves of the white myth: The psychology of neo-colonialism (Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, NJ, 1980).

- Lewis Gordon. Her Majesty's Other Children: Sketches of Racism from a Neocolonial Age (Rowman & Littlefield, 1997).

- Ankie M. M. Hoogvelt. Globalization and the postcolonial world: The new political economy of development (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

- J. M. Hobson, The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

- M. B. Hooker. Legal pluralism; an introduction to colonial and neo-colonial laws (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1975).

- E.M. Kramer (ed.) The emerging monoculture: assimilation and the "model minority" (Praeger, Westport, Conn., 2003). See: Archana J. Bhatt's "Asian Indians and the Model Minority Narrative: A Neocolonial System," pp. 203–221.

- Geir Lundestad (ed.) The fall of great powers: Peace, stability, and legitimacy (Scandinavian University Press, Oslo, 1994).

- Jean-Paul Sartre. 'Colonialism and neo-colonialism. Translated by Steve Brewer, Azzedine Haddour, Terry McWilliams Republished in the 2001 edition by Routledge France. ISBN 0-415-19145-9.

- Peccia, T., 2014, "The Theory of the Globe Scrambled by Social Networks: A New Sphere of Influence 2.0", Jura Gentium - Rivista di Filosofia del Diritto Internazionale e della Politica Globale, Sezione "L'Afghanistan Contemporaneo", http://www.juragentium.org/topics/wlgo/en/peccia.htm

- Stuart J. Seborer. U.S. neo-colonialism in Africa (International Publishers, NY, 1974).

- D. Simon. Cities, capital and development: African cities in the world economy (Halstead, NY, 1992).

- Phillip Singer(ed.) Traditional healing, new science or new colonialism": (essays in critique of medical anthropology) (Conch Magazine, Owerri, 1977).

- Jean Suret-Canale. Essays on African history: From the slave trade to neo-colonialism (Hurst, London 1988).

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. Barrel of a pen: Resistance to repression in neo-colonial Kenya (Africa Research & Publications Project, 1983).

- Carlos Alzugaray Treto. El ocaso de un régimen neocolonial: Estados Unidos y la dictadura de Batista durante 1958,(The twilight of a neocolonial regime: The United States and Batista during 1958), in Temas: Cultura, Ideología y Sociedad, No.16-17, October 1998/March 1999, pp. 29–41 (La Habana: Ministry of Culture).

- United Nations (2007). Reports of International Arbitral Awards. XXVII. United Nations Publication. p. 188. ISBN 978-92-1-033098-5.

- Richard Werbner (ed.) Postcolonial identities in Africa (Zed Books, NJ, 1996).

External links

- China, Africa, and Oil

- Mbeki warns on China-Africa ties

- "neocolonialism" in Encyclopedia of Marxism.

- Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, by Kwame Nkrumah (former Prime Minister and President of Ghana), originally published 1965

- Comments by Prof. Jeffrey Sachs - BBC

- Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs video (ram) - hosted by Columbia Univ.

- The myth of Neo-colonialism by Tunde Obadina, director of Africa Business Information Services (AfBIS)

- http://www.africahistory.net/imf.htm — IMF: Market Reform and Corporate Globalization, by Dr. Gloria Emeagwali, Prof. of History and African Studies, Conne. State Univ.

Academic course materials

- Sovereignty in the Postcolonial African State, Syllabus : Joseph Hill, University of Rochester, 2008.

- Studying African development history: Study guides, Lauri Siitonen, Päivi Hasu, Wolfgang Zeller. Helsinki University, 2007.