Noel Park

| Noel Park | |

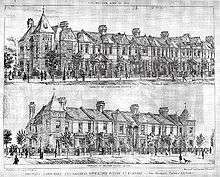

| Fourth-class houses in Darwin Road, built during the initial development of Noel Park in the 1880s |

|

Noel Park |

|

| Population | 5,670 [1] |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | TQ315902 |

| – Charing Cross | 6.4 mi (10.3 km) SSW |

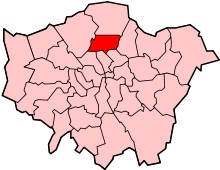

| London borough | Haringey |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | London |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | N22 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| EU Parliament | London |

| UK Parliament | Hornsey and Wood Green |

| London Assembly | Enfield and Haringey |

Coordinates: 51°35′47″N 0°06′08″W / 51.5965°N 0.1022°W

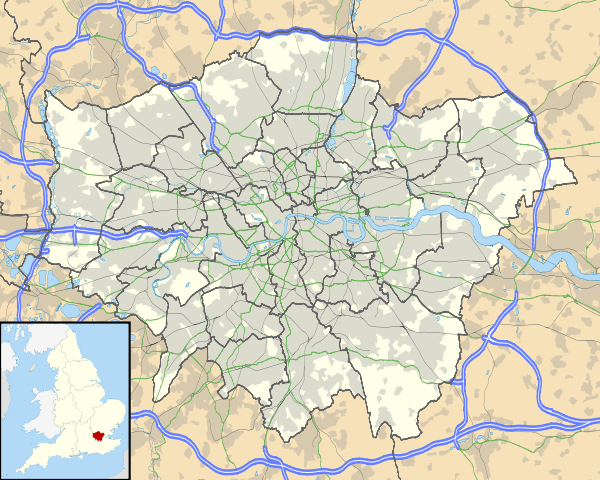

Noel Park in north London is a late-19th early 20th-century planned community consisting of 2,200 model dwellings, designed by Rowland Plumbe. It was developed in open countryside to the north of London in the valley of the River Moselle, about halfway between the historic villages of Highgate and Tottenham. It is one of four developments on the outskirts of London built by the Artizans, Labourers & General Dwellings Company (Artizans Company). From 2003 to sometime in 2009, the name was also given to a small park near the southern edge of Noel Park, formerly known, and now known again as Russell Park.

One of the earliest garden suburbs in the world, Noel Park was designed to provide affordable housing for working-class families wishing to leave the inner city; every property had a front and rear garden. It was planned from the outset as a self-contained community close enough to the rail network to allow its residents to commute to work. In line with the principles of the Artizans Company's founder, William Austin, no public houses were built within the estate, and there are still none today.

As a result of London's rapid expansion during the early 20th century, and particularly after the area was connected to the London Underground in 1932, Noel Park became completely surrounded by later developments. In 1965, it was incorporated into the newly created London Borough of Haringey, and in 1966 it was bought by the local authority and taken into public ownership.

Despite damage sustained during World War II and demolition work during the construction of Wood Green Shopping City in the 1970s, Noel Park today remains largely architecturally intact. In 1982, the majority of the area was granted Conservation Area and Article Four Direction status by the Secretary of State for the Environment, in recognition of its significance in the development of suburban and philanthropic housing and in the history of the modern housing estate.

Location

Noel Park is 6.4 miles (10.3 km) north of Charing Cross, near the centre of the modern London Borough of Haringey, of which it is a ward. The area forms a rough triangle, bordered by the A109 road (Lordship Lane) to the north, A1080 road (Westbury Avenue) to the south-east, and A105 road (Wood Green High Road, formerly part of Green Lanes) to the west.

When construction began, the River Moselle, running parallel to Lordship Lane a short distance south of it, formed the de facto northern boundary of the area. During the development of the area in the 1880s the river was culverted and the land between the river and Lordship Lane built on.[2]

The historic western boundary was the now-defunct Palace Gates Line of the Great Eastern Railway (GER), a short distance to the east of Wood Green High Road. Since the railway's closure in 1964, much of the area between the former railway line and Wood Green High Road has been occupied by the eastern section of the large The Mall Wood Green shopping, cinema and residential complex (commonly known as Shopping City).[2]

History and development

Early history

Historically, the site of Noel Park was virtually uninhabited. The 1619 Earl of Dorset's Survey of Tottenham shows the area as forming the historic Duckett's (Dovecote) Manor; as with the rest of the Moselle valley the land consisted almost entirely of woodland and pasture, with the only building shown in the area which was to become Noel Park being Dovecote House itself, dating from 1254 and the earliest recorded property in Wood Green.[4] The small village of Wood Green itself is shown a short distance to the north-east. The manor itself was situated on the ancient arterial road of Green Lanes.[5] The last recorded occupancy of the manor was in 1881, shortly before the site was cleared for the construction of Noel Park.[6]

By 1880 the estate had been broken up into fifteen smaller farms. The rough northern meadows adjacent to the Moselle were used for beef farming, whilst the southern fields, known as Grainger's Farm, were used as grazing land.[4] The western edge of the estate was by this time occupied by the Great Eastern Railway's Palace Gates Line and Green Lanes railway station, opened in 1878.[7]

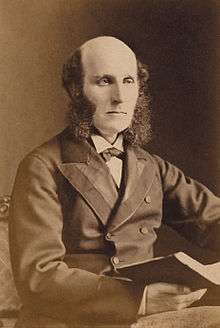

Artizans, Labourers & General Dwellings Company

The Artizans, Labourers & General Dwellings Company (Artizans Company) was established in 1867 by William Austin. Austin was an illiterate who had begun his working life on a farm as a scarecrow paid 1d per day,[8] and had worked his way up to become a drainage contractor.[9] The company was established as a for-profit joint stock company, with the objective of building new houses for the working classes "in consequence of the destruction of houses by railroads and other improvements".[9][10] The company aimed to fuse the designs of rural planned suburbs such as Bedford Park with the ethos of high-quality homes for the lower classes pioneered at Saltaire.[11] Whilst earlier philanthropic housing companies such as the Peabody Trust and the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company focused on multi-storey blocks of flats in the inner cities, the Artizans Company aimed to build low-rise housing in open countryside alongside existing railway lines to allow workers to live in the countryside and commute into the city.[12] The company attracted the attention of Lord Shaftesbury, who served as president until 1875.[9]

The company built and immediately sold a group of houses in Battersea, then still a rural village. The proceeds of the sale were used to purchase a plot of land in Salford for development, and by 1874 the company had developments in Liverpool, Birmingham, Gosport and Leeds.[9]

The first of the four large-scale estates built by the Artizans Company was Shaftesbury Park, a development of 1,200 two-storey houses covering 42.5 acres (0.17 km2; 0.07 sq mi) built in 1872 on the site of a former pig farm in Battersea.[9][12] The success of Shaftesbury Park led to the construction of Queen's Park, built in 1874 on a far more ambitious scale on 76 acres (0.31 km2; 0.12 sq mi) of land to the west of London, adjacent to the newly opened Westbourne Park station, purchased from All Souls College, Oxford. A third London estate was planned at Cann Hall, and a site of 61 acres (0.25 km2; 0.10 sq mi) was purchased.[9]

However, the Queen's Park project suffered serious mismanagement and fraud; the company secretary William Swindlehurst and two others were found guilty in 1877 of defrauding £9,312 (approximately £791 thousand today) from the project.[13][14] The company was forced to raise rents and tenants were no longer permitted to buy their houses; by 1880 the company's finances had recovered sufficiently to allow further expansion.[15]

Selection of the site

On 14 February 1881, Rowland Plumbe was appointed Consulting Architect to the Artizans Company, with a brief to prepare a third estate. A leading architect of the period, Plumbe had primarily been a designer of hospitals, such as the London Hospital,[15] and Poplar Hospital;[16] he had been President of the Architectural Association in 1871–72 and a Council Member of the Royal Institute of British Architects since 1876.[15]

In April 1881, the Artizans Company inspected sites at Fulham and "in the vicinity of Alexandra Park" in the Tottenham Local Board. The Fulham site was rejected as too prone to flooding, and the Wood Green site rejected as being too far from any centre of population.[4]

However, the next month, the decision was taken to bid for the site near Wood Green.[4] Despite its distance from London at the time, the area was well served by railways. The Palace Gates Line, opened in 1878 to serve nearby Alexandra Palace, had an intermediate station at Green Lanes, immediately adjacent to the site in question.[17] This provided direct service to the City of London from the outset; following the construction of a link with the Tottenham and Hampstead Junction Railway on 1 June 1880, direct services also ran to Blackwall and North Woolwich, providing direct links with the Port of London.[18] In addition, the Great Northern Railway's station at Wood Green (now Alexandra Palace station) was within walking distance. The company decided that the quality of transport links compensated for the distance from any significant centre of population, and, in June 1881, a site of 100 acres (0.40 km2; 0.16 sq mi) was purchased by the company for £56,345 (approximately £5.13 million today).[14][19]

Design

Plumbe designed the estate with five classes of houses, all built in the Gothic Revival style. Although the houses were built to the same five basic designs, each street was given a distinct style of design and ornamentation. Varying mixes of red and yellow bricks, and variations in window design and ornamental motifs were used to give each street a distinct identity.[20] All were designed with front and rear gardens.[21] Corner houses were given distinctive designs and turrets.[22]

The distribution of houses followed the traditional Victorian model of town planning. The larger first- and second-class houses were built in the centre, close to the church and school, while the more numerous third-, fourth- and fifth-class houses were built in the estate's outskirts.[23] Welch (2006) speculates that this segregation of housing was not Plumbe's intention;[23] Plumbe himself was quoted in 1896 as saying that "I regret that it is necessary to separate the richer and more cultured classes from the poorer, owing to the prejudices which exist; and these prejudices exist on the part of the poor as well as on the part of the other class".[24]

Except for the corner houses, the houses were built in pairs, each sharing a porch with its neighbour.[21] For many of the smaller fourth- and fifth-class houses, the doors were aligned at right angles to the façade of the house, so as not to open directly adjacently to their neighbours. All houses were designed with at least one parlour and with the kitchen, scullery, and toilet in separate rooms at the rear of the house; the first-class houses also had toilets upstairs.[25] In line with the design principles of the time, the downstairs toilets were accessible only from the rear gardens, and the houses were not fitted with separate bathrooms; baths were taken in a moveable bath located in the kitchen.[25]

All houses were built with marble-mantelpieced fireplaces and flues. All houses were supplied with running water supplied from the New River, which flowed through nearby Wood Green.[25] However, not all houses were supplied with gas or mains electricity from the outset, the remainder being lit by candles or oil or paraffin lamps.[25]

Houses at Noel Park were deliberately designed to be relatively small, both for cheapness and to discourage tenants from taking on lodgers.[26] Many of the larger houses at Shaftesbury Park had been sublet and split, and the practice went against the principles of the Artizans Company's founders.[21] To discourage the practice at Queen's Park and Noel Park cottage flats were built; these maintained the terraced façade, but split the house into upper and lower flats, each flat having a separate front door onto the street.[21] Many properties, particularly on the central Gladstone Avenue, were built in this style; this maintained the unbroken façade of the first-class houses, but allowed large numbers of smaller and low-income families to be housed.

Construction

On 4 May 1883, the Artizans Company sold a parcel of land adjacent to the railway line to the Great Eastern Railway for construction of a goods yard, and a siding was built into the development site.[27][28] Although initially the company had considered making bricks on the site, the rail yard allowed raw materials to be purchased wholesale and transported cheaply to the site, with large warehouses and workshops constructed for the manufacture of doors, flooring and other necessary materials; in 1884 the Pall Mall Gazette reported that "in a shed 330ft long by 50ft broad are stored a million superficial feet of flooring boards".[28]

In early 1883 serious discrepancies were discovered between the amounts of building material apparently purchased and the actual amounts acquired. Rowland Plumbe and Sir Richard Farrant, Deputy Chairman of the Artizans Company, visited the site to investigate the matter. Mr Hunt, the foreman, advised that "in answer to questions as to the mode of measurement in use for Ballast heaps, that one third was added to the measurement for shrinkage".[29]

When summoned to appear before the "Hornsey Committee" of the Artizans Company the next day, Hunt instead sent his assistant, without the relevant ledgers and instead with a paper described in the Committee minutes as "a paper of measurements which were soon ascertained not to be the actual measurements but measurements falsified so as to work out cubically to about the measurements certified by Mr Hunt".[30] The total overpaid by the company was calculated by Plumbe as £1,071.14s.3d (approximately £97.3 thousand today); Hunt was immediately dismissed and a gatekeeper to record all goods entering the site was put in place to avoid a repetition of the incident.[14][29]

In 1883, it was decided to name the estate "Noel Park", in honour of Ernest Noel (1831–1931), Liberal Member of Parliament for Dumfries Burghs and chairman of the Artizans Company since 1880.[31] The streets were laid out on a grid plan of broad avenues running on a south-west to north-east axis and narrower roads running north-west to south-east. Streets were named after prominent members of the Artizans Company and leading political figures of the time, with the exception of Darwin Avenue, named for Charles Darwin, prominent naturalist and an early investor in the Artizans Company, and Moselle Avenue, which was to follow the course of the culverted River Moselle; see Derivation of street names, below.[32]

Opening

On 4 August 1883, with approximately 200 houses completed, Noel Park was formally opened. Noel gave a speech at the opening ceremony in which he described the development as:

... what, out of the metropolis, would be called a town, which would eventually ... be larger than the Royal Borough of Windsor and nearly as large as the old cathedral city of Canterbury. But this town would not contain various classes of population, but would be built for the express purpose of meeting the wants of the artisan classes, so that they whose resources are limited should be enabled to reside amid pleasant surroundings.[31]

Lord Shaftesbury then laid the memorial stone, praising Noel Park as "the furtherance of a plan which has proved to be most beneficial, and would, if carried out to its full extent, completely alter for the better the domiciliary habits of the people of the metropolis".[33] Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury, sent a note which was read to the crowd in which he stated that "no one who cares for our labouring population can doubt that this is one of the first, perhaps the most, necessary of all steps for their good".[34][35]

Financial difficulties

Noel Park was heavily marketed as a "Suburban Workman's Colony", with promotional material playing heavily on the area's transport links. The Great Eastern Railway was persuaded in 1884 to rename Green Lanes railway station to "Green Lanes (Noel Park)" (shown on some signs and maps as "Green Lanes & Noel Park");[17] the area was also less than half a mile from Wood Green railway station (now Alexandra Palace station) on the Great Northern Railway. By 1886 Noel Park had over 7,000 residents.[36]

However, the poor workers at whom the Noel Park development was aimed found themselves unable to afford railway tickets. The issuing of cheap early morning workman's fares on the Great Eastern Railway's lines further east in Tottenham, Stamford Hill and Walthamstow had led to overcrowding on trains and large numbers of poor workers moving to the areas (many of them displaced by the construction of the GER's Liverpool Street station in the City of London and rehoused by the company).[37] William Birt, General Manager of the GER was strongly against extending the policy of workmen's fares, stating that "to issue them from Green Lanes would do us a very large amount of injury, and would cause the same public annoyance and inconvenience as exists already upon the Stamford Hill and Walthamstow lines" and that "no one living in Noel Park could desire to possess the same class of neighbours as the residents of Stamford Hill have in the neighbourhood of St Ann's Road".[38]

In 1884, a deputation led by Lord Shaftesbury was made to the Great Eastern Railway and Great Northern Railway, proposing that for trains due to arrive in central London prior to 8 am, third class tickets should be sold at a fare of 3d providing the return journey was not made before 4 pm. By May 1885 both railways had adopted this policy. However, the delays and uncertainty caused by the fares dispute had discouraged prospective tenants, leaving large numbers of properties vacant and causing further building work to slow considerably.[39] In 1887, construction work was temporarily suspended altogether, in response to the large backlog of un-let properties.[36]

By the time of the 1894 Ordnance Survey, roughly 50% of the estate was complete.[39] The entire southern half of the estate between Gladstone Avenue and Westbury Avenue at this point remained open fields.[36]

Amenities

Terraces of shops were built around the fringes of the estate, both to cater for the residents of Noel Park and for residents of the expanding suburb of Wood Green and the users of the adjacent railway station. The designs of the terraces varied, from short terraces of small shops on the edges of the less-visited eastern portions of the estate, to parades of large shops on Wood Green High Road near the railway station.[40]

One of the few buildings constructed in the early stages of Noel Park's development not designed by Rowland Plumbe, Noel Park School was built in 1889 by the Wood Green School Board, to the design of architect Charles Wall.[41]

The school was designed to accommodate 1,524 pupils of both sexes; however, by 1898 the growth of the Noel Park estate led to severe overcrowding problems, with an average attendance of 1,803, making it the most overcrowded school in the School Board's area. In 1924 a school for the partially blind opened within the school.[42]

In 1946, the school became a Secondary Modern. Between 1957 and 1963 the secondary facilities were closed, leaving the school as a primary school.[43] In 1965, the school came under the control of the newly created London Borough of Haringey.[42] Following reorganisation of Haringey's education services, it is now a primary school serving approximately 500 pupils between the ages of three and 11.[44]

Although Plumbe's original plans for the estate had envisaged a recreational area in the centre of the estate, this never came into being and the land reserved for it was built over during the estate's early development. Despite Noel Park's proximity to the leisure facilities of nearby Alexandra Park, in 1929 a long, thin strip of land near the south of the estate was designated as parkland and given the name "Russell Park". In 2003, following consultation with residents, the park was renamed "Noel Park" by Haringey Council.[41] Its name has since been changed back to Russell Park.[45]

A site for a church had been set aside on the estate from the outset, and in 1884 Plumbe submitted designs for a church and mission hall. The mission hall opened in March 1885 with room for 350, and soon began to suffer from overcrowding. The people of Noel Park started a fund to pay for the church, which was consecrated on 1 November 1889 as St Mark's.[46]

The church is relatively large, seating 850.[47] It is built in the Venetian Gothic style, and divided into a five-bay nave, transepts, chancel, morning chapel and organ chamber.[47] Although Plumbe's original design envisaged a tower, one was never built. By 1900, St Mark's was reported as having a congregation twice that of any other church in Wood Green.[46]

In 1913, a second much larger mission hall was opened nearby, named the Walsham-How Mission Hall after William Walsham How, leader of the Shropshire Mission to East London.[46] The Shropshire Hall, built by the Shropshire Mission in Gladstone Avenue, is now the Noel Park Children's Centre.[48] Noel Park's relative geographic isolation led to the formation of large numbers of clubs and societies using the two mission halls for a wide range of activities, including large numbers of sporting societies.[41]

Due to the temperance views of the Artizans Company's directors, no public houses were built in Noel Park, a situation which remains the case today.[49]

20th century

Early 20th-century expansion

In 1905, G. J. Earle, the Artizans Company's Surveyor, drew up plans for the remainder of the site based on the experiences learned from the completed northern half of the estate. Buildings were designed to a modified version of Plumbe's third-class house plan in the Arts and Crafts style, with white-rendered brickwork, regular low gables, and curved ground floor windows. The toilets were now designed with connecting doors to the sculleries, and in some cases the staircases repositioned to the front of the house. They were no longer described or marketed as "third-class" houses.[50]

By October 1906 1,999 properties were let, including 88 shops and 4 stables. Although the estate was nearing completion by this point, construction work was not entirely completed until 1929.[50]

By this point, the Noel Park development and the growing nearby community of Wood Green were coming to dominate the area. In recognition of this, in 1902 Green Lanes railway station was renamed Noel Park & Wood Green.[17] In 1911 a group of mid-Victorian houses on Wood Green High Road, immediately south of the railway station, were demolished by the Artizans Company to make way for the Cheapside shopping parade, built to serve residents of Noel Park and the growing community of Wood Green.[51]

The centrepiece of the Cheapside development was the Wood Green Empire, a 3,000-capacity theatre designed by Frank Matcham. The Empire soon became one of London's leading entertainment venues, hosting acts such as Marie Lloyd, Frankie Vaughan and Shirley Bassey. The Empire is best known as the theatre in which magician Chung Ling Soo (William Ellsworth Robinson) was fatally shot in the chest on 23 March 1918, when a theatrical pistol used in a bullet catch demonstration malfunctioned.[52]

With the postwar decline of variety and music hall and increased competition from cinema and television, the theatre went into decline and was closed on 31 January 1955. Following its closure it was used by Associated TeleVision as a studio until 1963. The interior was demolished in 1970, but the building remains intact and is now used as a shop and offices.[2]

Piccadilly line

In 1904 the Great Northern & City Railway underground railway had opened, running from the City of London to a terminus at Finsbury Park station, followed in 1906 by the Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (GNP&BR) from the western suburbs through central London to Finsbury Park, approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Noel Park; both were prevented from expanding further north by a legal agreement with the Great Northern Railway giving the GNR a veto on any expansion of underground railways into areas within which they would compete with the GNR.[53] This led to serious congestion at Finsbury Park as passengers from the expanding suburbs changed from buses and trams to the GN&CR and GNP&BR, and in June 1923 a petition of 30,000 signatures calling for the extension of one of the underground lines northwards was delivered to the Ministry of Transport.[53]

The London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), successor to the GNR, was compelled by the Ministry of Transport to waive the veto or proceed with its own electrification. In November 1925, the LNER abandoned its electrification scheme. In 1929 the incoming Second Labour Government initiated a policy of direct subsidy for major infrastructure projects, and, in 1930, the Underground Electric Railways Company of London began work on extending the GNP&BR, now the Piccadilly line.[54] The Piccadilly line extension to Cockfosters opened in stages, with stations at Wood Green and Turnpike Lane – both on the western edge of Noel Park, at the junctions of Wood Green High Road and Lordship Lane, and Wood Green High Road and Westbury Avenue, respectively – opening on 19 September 1932.[55] With the area now connected to west and central London by clean, rapid and frequent electric trains, the population of the surrounding areas began to rise rapidly.[56]

Postwar reconstruction

Although of little strategic value and undamaged during the early stages of World War II, in the final stages of the war a number of V-1 flying bombs and V-2 ballistic missiles struck the area. The worst attack occurred in February 1945, when a V-2 struck Westbeech Road, killing 17 and injuring 68. The bombsites were redeveloped with housing in then-current styles, rather than to Plumbe and Earle's designs.[2]

In 1958, as part of the commemorations of the 70th anniversary of the creation of the Wood Green Local Board, the railway goods depot was used for a three-day exhibition of locomotives and other railway rolling stock. The exhibition was a great success, and was visited by around 14,000 spectators.[27] Among locomotives on exhibit were the land speed record holder Mallard and a Class 9F steam locomotive.[57]

However, by this point the Palace Gates Line was in severe decline. Passenger numbers had fallen greatly since the opening of the Piccadilly line, while freight usage dropped throughout the 1950s as a result of improved road haulage and declining demand for coal. The line was closed to passengers on 7 January 1963.[7] With freight usage dwindling to a trickle following the ending of passenger services, the goods yard was closed on 7 December 1964.[27] The site of the goods yard was used for the construction of a large apartment block known as The Sandlings,[2] and Noel Park & Wood Green railway station was converted into commercial premises, before being demolished in the early 1970s to become the site of the eastern section of Wood Green Shopping City.[17]

Transfer to local authority control

In 1952, the Artizans, Labourers & General Dwellings Company was renamed the Artizans and General Properties Company Ltd.[9] The combination of a taxation system biased against private property developments and legal restrictions on raising rents made the company's traditional model unprofitable, and it began to divest itself of its original low-rent developments and instead to sell vacant houses on the estates and to reinvest in non low-rent housing and commercial property, especially in the United States and Canada where depreciation before tax was permitted.[9] In 1966, ownership of the four original London estates (Shaftesbury Park, Queen's Park, Noel Park and Leigham Court) was transferred to the respective local authorities as council housing – in the case of Noel Park, the newly created London Borough of Haringey, which purchased the 2,175 properties comprising the Noel Park estate for a total of £2,917,000 (approximately £49 million today)[14][58] – leaving 377 homes at Pinnerwood Park in Pinner as the last residential estate in Greater London owned by the company.[9]

In 1976, the Artizans Company, by then renamed Artagen Properties Ltd, became a wholly owned subsidiary of Sun Life, and on, 3 February 1981, the company was renamed Sun Life Properties Ltd.[9]

Modern Noel Park

Following the transfer to local authority control, much of the property on the estate was found to be in poor condition. In 1971 a report by the London Borough of Haringey found that half the properties on the estate were still lacking basic facilities such as baths, internal toilets and hot water. Houses were systematically extended to the rear to accommodate modern bathrooms.[58]

In the early 1970s, the nine-storey Wood Green Shopping City shopping, cinema and residential complex was built on both sides of Wood Green High Road, and now dominates the area. Although some houses were demolished during construction works, it was intended at the time to divert Wood Green High Road around Shopping City, which would have necessitated the demolition of much of the western section of Noel Park. However, the diversion scheme was abandoned, leading to the current unusual situation in which the road runs directly through the shopping centre; Cherry & Pevsner note that Noel Park was "spared worse damage by the abandonment of the proposed road".[59]

In 1980, the Housing Act 1980 gave council tenants the right to buy their homes. In light of this, a group of 1500 properties in the area was given Conservation Area status,[58] and Plumbe's northern section of the estate was granted Article Four Direction by Michael Heseltine, Secretary of State for the Environment, preventing any alterations to the external appearances of the properties without planning permission, in recognition of its architectural and historic interest.[60] St Mark's Church was meanwhile Grade II listed.[58] However, these measures have not been consistently enforced, and Noel Park has been cited in a report by English Heritage as a prominent example of the failure of conservation areas.[61][62]

Throughout the eighties and early nineties the estate was the home of a large squatter community, mostly made up of young punks from Ireland, Wales, Scotland and outside London which greatly enlivened the area but also led to many legal and other conflicts with Haringey Council who ironically had left so many of the properties empty in the first place. Many of these were later to move to the Woodberry Down Estate in Manor House.

In line with the original principles of the Artizans Company, there are still no public houses in Noel Park. In 2008 parts of Noel Park and the surrounding area were declared a Controlled Drinking Zone, allowing police to confiscate alcohol from those engaged in anti-social behaviour.[63]

As with much of Haringey, Noel Park is now one of the most ethnically diverse areas in the world. In 2002, 86% of pupils attending Noel Park School were from ethnic minorities.[1]

Derivation of street names

- Ashley Crescent: Evelyn Ashley, MP for Isle of Wight, son of Lord Shaftesbury and Chairman of the Artizans Company

- Buller Road: Redvers Buller, winner of the Victoria Cross at the Battle of Hlobane, 1879

- Darwin Road: Charles Darwin, naturalist and early investor in the Artizans Company

- Dovecote Avenue: On the site of the original Duckett's (Dovecote) Manor, by this time demolished

- Farrant Avenue: Sir Richard Farrant, Deputy Chairman of the Artizans Company 1881–1906

- Gladstone Avenue: William Ewart Gladstone, Prime Minister at the time of the opening of Noel Park

- Hewitt Avenue: Thomas Hewitt QC, Director of the Artizans Company 1895–1917

- Lymington Avenue: Viscount Lymington, Director of the Artizans Company 1883-1891

- Mark Road: Mark H Judge, Director of the Artizans Company 1878–1922

- Maurice Avenue: Maurice Powell, Director of the Artizans Company 1880–1914

- Morley Avenue: Samuel Morley, MP for Bristol and Director of the Artizans Company 1877–1880

- Moselle Avenue: Runs above the culverted River Moselle

- Pelham Road: T W Pelham, Director of the Artizans Company 1880–1894

- Redvers Road: Redvers Buller (see Buller Road, above)

- Russell Avenue: John Russell, former Liberal Prime Minister

- Salisbury Road: Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, leader of the Conservative Party

- Vincent Road: Unknown; Welch speculates from Rev. Henry Vincent Le Bas, the only member of the Noel Park Committee at the time of opening not known to have had a street named for him[32]

References

Notes

- 1 2 Garner, Kate (2008-12-08). "Noel Park Facts and Figures". London Borough of Haringey. Archived from the original on 2009-05-03. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Welch, p. 48

- ↑ From the Earl of Dorset's Survey of Tottenham, 1619. As with most English maps of this period, south is shown at the top of the map. The river in the centre of the map is the Moselle, whilst the "river" passing through Wood Green to the north-west is the New River, opened six years prior to the survey.

- 1 2 3 4 Welch, p. 11

- ↑ The section of Green Lanes between Turnpike Lane and Wood Green stations, which forms the western boundary of modern Noel Park, has since been renamed "Wood Green High Road".

- ↑ Baker, T. F. T.; Pugh, R. B., eds. (1976). "Tottenham: Manors". A History of the County of Middlesex. London. 5: 324–330. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- 1 2 Connor, p. VIII

- ↑ Long, p. 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Sun Life Properties Ltd". IV/122. The National Archives. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ↑ Welch, p. 8

- ↑ Welch, p. 7

- 1 2 Welch, p. 9

- ↑ "Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court". The Old Bailey Online Project. 22 October 1877. p. 8. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- 1 2 3 Welch, p. 10

- ↑ Hobhouse, Hermione (ed) (1994). "East India Dock Road, North side". Survey of London. 43–44: 147–153. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- 1 2 3 4 Connor, § 109

- ↑ Lake, p. 23

- ↑ Welch, p. 12

- ↑ Welch, p. 25

- 1 2 3 4 Welch, p. 30

- ↑ Welch, p. 27

- 1 2 Welch, p. 32

- ↑ London newspaper, 1896-05-28, quoted in Welch, p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 Welch, p. 28

- ↑ Tarn, p.58

- 1 2 3 Connor, § 108

- 1 2 Welch, p. 15

- 1 2 Welch, p. 17

- ↑ Minutes of the Hornsey Committee of the Artizans Company, 8 January 1883, quoted Pegram, p17

- 1 2 Welch, p. 18

- 1 2 Welch, p. 23

- ↑ Welch, p. 19

- ↑ "I assure you of my sympathy with the work which the Artizans Dwelling Company is attempting in the important direction of improving the houses of the working men. No one who cares for our labouring population can doubt that this is one of the first, perhaps the most, necessary of all steps for their good."

- ↑ Welch, p. 20

- 1 2 3 Baker, T. F. T.; Pugh, R. B., eds. (1976). "Tottenham: Growth after 1850". A History of the County of Middlesex. London. 5: 317–324. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ Connor, p. V

- ↑ Olsen, p. 290

- 1 2 Welch, p. 21

- 1 2 3 Welch, p. 45

- 1 2 3 Welch, p. 41

- 1 2 Welch, p. 44

- ↑ Baker, T. F. T.; Pugh, R. B., eds. (1976). "Tottenham: Education". A History of the County of Middlesex. London. 5: 364–376. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ "Noel Park Primary School". London Borough of Haringey. 2008-10-27. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ "Russell Park". Haringey Council.

- 1 2 3 Welch, p. 39

- 1 2 Baker, T. F. T.; Pugh, R. B., eds. (1976). "Tottenham: Churches". A History of the County of Middlesex. London. 5: 348–355. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ Welch (p. 39) states that the current Shropshire Hall on Gladstone Avenue is the original 1913 Walsham-How Mission Hall building. However, pictorial evidence of the 1913 building at the time of construction and the 1920 Ordnance Survey map suggests that the original building is that sited off Willington Road opposite the junction with Lakefield Road, a short distance south of the current Shropshire Hall, with the latter being a later construction.

- ↑ Brian Harrison, Pubs, Dyos and Wolff, p. 183

- 1 2 Welch, p. 35

- ↑ Welch, p. 36

- ↑ Welch, p. 46

- 1 2 Croome, p. 26

- ↑ Croome, p. 28

- ↑ Croome, p. 30

- ↑ Croome, p. 44

- ↑ Martin, Ted (June 2004). "Transport in Wood Green in the 1950s". Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society. London: GLIAS. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- 1 2 3 4 Welch, p. 50

- ↑ Cherry & Pevsner, p. 594

- ↑ "Design Guidelines: Noel Park Conservation Area" (PDF). London Borough of Haringey. July 1983. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ↑ Jack, Ian (2009-06-27). Beware the double-glazing salesman. The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ "Historic estate 'on the road to ruin'". Tottenham, Wood Green and Edmonton Journal. London. 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ Fontaine, Valley (2008-04-21). "Further alcohol controls for Haringey Streets". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

Bibliography

- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998). The Buildings of England. London 4: North. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-071049-3. OCLC 40453938.

- Connor, Jim (2004). Vic Mitchell, ed. Branch Lines to Enfield Town and Palace Gates. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-904474-32-2.

- Croome, Desmond F. (1998). The Piccadilly Line. Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-192-9.

- Jim Dyos & Michael Wolff, ed. (1999). The Victorian City. 1. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-19323-0.

- Lake, G.H. (1945). The Railways of Tottenham. London: Greenlake Publications Ltd. ISBN 1-899890-26-2.

- Long, Helen (2002). Victorian Houses and Their Details: The Role of Publications in Their Building and Decoration. Architectural Press. ISBN 0-7506-4848-1.

- Olsen, Donald J (1976). The Growth of Victorian London. London: Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-3229-2. OCLC 185749148.

- Tarn, John Nelson (1973). Five Per Cent Philanthropy: An account of housing in urban areas between 1840 and 1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-08506-3. OCLC 875501.

- Welch, Caroline (2006). Noel Park: A Social and Architectural History. London: Haringey Council Libraries, Archives & Museum Services. OCLC 123373636.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Noel Park. |

- Noel Park Official site of Haringey Council's Noel Park Neighbourhood Management Service

- A history of Noel Park

- Noel Park Conservation Area Advisory Committee

- Noel Park North Area Residents Association

- St Mark's Church

- The Salvation Army, Wood Green