Octopus

| Octopus Temporal range: 323.2–0 Ma Late Carboniferous – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Superorder: | Octopodiformes |

| Order: | Octopoda Leach, 1818[1] |

| Suborders | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The octopus (/ˈɒktəpʊs/ or /ˈɒktəpəs/; plural: octopuses, octopodes or octopi; see below) is a cephalopod mollusc of the order Octopoda. It has two eyes and four pairs of arms and, like other cephalopods, it is bilaterally symmetric. It has a beak, with its mouth at the center point of the arms. It has no internal or external skeleton (although some species have a vestigial remnant of a shell inside their mantles),[3] allowing it to squeeze through tight places.[4] Octopuses are among the most intelligent and behaviorally diverse of all invertebrates.

Octopuses inhabit diverse regions of the ocean, including coral reefs, pelagic waters, and the ocean floor. They have numerous strategies for defending themselves against predators, including the expulsion of ink, the use of camouflage and deimatic displays, their ability to jet quickly through the water, and their ability to hide. They trail their eight arms behind them as they swim. All octopuses are venomous, but only one group, the blue-ringed octopus, is known to be deadly to humans.[5]

Around 300 species are recognized, which is over one-third of the total number of known cephalopod species. The term "octopus" may also be used to refer specifically to the genus Octopus.

Etymology and pluralization

The scientific Latin term octopus was derived from Ancient Greek ὀκτώπους (oktōpous, "eight-footed"), a compound form of ὀκτώ (oktṓ, "eight") + πούς (poús, "foot").[6][7][8] Related to the word "octopus" are the terms "Octopoda" (the taxonomic order of cephalopod molluscs that comprises the octopuses) and the adjectival octopoid (with the suffix -oid, which signifies a resemblance to, but distinction from, something).[9]

The standard pluralized form of "octopus" in the English language is "octopuses" /ˈɒktəpʊsɪz/,[10] although the Ancient Greek plural "octopodes" /ɒkˈtɒpədiːz/, has also been used historically.[9] The alternative plural "octopi" – which misguidedly assumes it is a Latin "-us"-word – is considered grammatically incorrect.[11][12][13][14] It is nevertheless used enough to make it notable, and was formally acknowledged by the descriptivist Merriam-Webster 11th Collegiate Dictionary and Webster's New World College Dictionary. The Oxford English Dictionary (2008 Draft Revision)[15] lists "octopuses", "octopi", and "octopodes", in that order, labelling "octopodes" as rare and noting that "octopi" derives from the apprehension that octōpus comes from Latin.[16] In contrast, New Oxford American Dictionary (3rd Edition 2010) lists "octopuses" as the only acceptable pluralization, with a usage note indicating "octopodes" as being still occasionally used but "octopi" as being incorrect.[17]

Biology

Octopuses are characterized by their eight arms, usually bearing suction cups. The arms of octopuses are often distinguished from the pair of feeding tentacles found in squid and cuttlefish.[18] Both types of limb are muscular hydrostats.

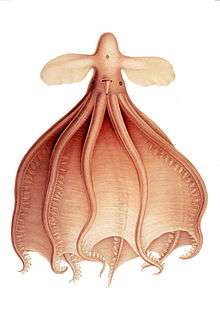

Octopuses can be divided into two suborders, the Incirrina (or Incirrata) and the Cirrina (or Cirrata). The incirrate octopuses are distinguished from the cirrate octopuses by their absence of "cirri" filaments (found with the suckers), as well as by the lack of paired swimming fins on the head. Unlike most other cephalopods, the majority of octopuses – those in the Incirrina – have almost entirely soft bodies with no internal skeleton. They have neither a protective outer shell like the nautilus, nor any vestige of an internal shell or bones, like cuttlefish or squid. The beak, similar in shape to a parrot's beak, and made of chitin, is the only hard part of their bodies. This enables them to squeeze through very narrow slits between underwater rocks, which is very helpful when they are fleeing from moray eels or other predatory fish. The octopuses in the less-familiar Cirrina suborder have two fins and an internal shell, generally reducing their ability to squeeze into small spaces. These cirrate species are often free-swimming and live in deep-water habitats, while incirrate octopus species are found in reefs and other shallower seafloor habitats.

Octopuses have a relatively short life expectancy, with some species living for as little as six months. Larger species, such as the giant pacific octopus, may live for up to five years under suitable circumstances. However, reproduction is a cause of death: males can live for only a few months after mating, and females die shortly after their eggs hatch. They neglect to eat during the (roughly) one-month period spent taking care of their unhatched eggs, eventually dying of starvation. In a scientific experiment, the removal of both optic glands after spawning was found to result in the cessation of broodiness, the resumption of feeding, increased growth, and greatly extended lifespans.[19]

Octopuses have three hearts. Two branchial hearts pump blood through each of the two gills, while the third is a systemic heart that pumps blood through the body. Octopus blood contains the copper-rich protein hemocyanin for transporting oxygen. Although less efficient under normal conditions than the iron-rich hemoglobin of vertebrates, in cold conditions with low oxygen pressure, hemocyanin oxygen transportation is more efficient than hemoglobin oxygen transportation. The hemocyanin is dissolved in the plasma instead of being carried within red blood cells, and gives the blood a bluish color. The octopus draws water into its mantle cavity, where it passes through its gills. As molluscs, octopuses have gills that are finely divided and vascularized outgrowths of either the outer or the inner body surface.

Intelligence

Octopuses are highly intelligent, possibly more so than any other order of invertebrates. The exact extent of their intelligence and learning capability is much debated among biologists,[20][21][22][23] but maze and problem-solving experiments have shown evidence of a memory system that can store both short- and long-term memory. It is not known precisely what contribution learning makes to adult octopus behavior. Young octopuses learn almost no behaviors from their parents, with whom they have very little contact.[24]

As stated above, even the octopuses that have the longest lifespan (the Giant Pacific Octopus) simply don't live long enough after the young are born to teach them very much. Approximately 6 weeks after mating, the female lays 20,000–100,000 eggs over the course of several days on the inner side of her rocky den. For the next 5–8 months she tends the eggs, carefully cleaning and aerating them until they hatch. The female does not leave her brood, even to eat, and will die within weeks or months after they hatch, gradually becoming weaker as she dies of starvation. The male dies shortly after mating. The typical life span of the octopus is between 3–5 years.

The octopus has a highly complex nervous system, only part of which is localized in its brain. Two-thirds of an octopus's neurons are found in the nerve cords of its arms, which have limited functional autonomy. Octopus arms show a variety of complex reflex actions that persist even when they have no input from the brain.[25] Unlike vertebrates, the complex motor skills of octopuses are not organized in their brain using an internal somatotopic map of its body, instead using a nonsomatotopic system unique to large-brained invertebrates.[26] Despite this delegation of control, octopus arms do not become tangled or stuck to each other because the suction cups have chemical sensors that recognize octopus skin and prevent self-attachment.[27] Some octopuses, such as the mimic octopus, will move their arms in ways that emulate the shape and movements of other sea creatures.

In laboratory experiments, octopuses can be readily trained to distinguish between different shapes and patterns. They have been reported to practice observational learning,[28] although the validity of these findings is widely contested on a number of grounds.[20][21] Octopuses have also been observed in what some have described as play: repeatedly releasing bottles or toys into a circular current in their aquariums and then catching them.[29] Octopuses often break out of their aquariums and sometimes into others in search of food.[30][31][32] They have even boarded fishing boats and opened holds to eat crabs.[22]

Tool use

The octopus has been shown to use tools. At least four specimens of the veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) have been witnessed retrieving discarded coconut shells, manipulating them, and then reassembling them to use as shelter.[33][34][35]

Protective legislation

Due to their intelligence, octopuses in some countries are on the list of experimental animals on which surgery may not be performed without anesthesia, a protection usually extended only to vertebrates. In the UK from 1993 to 2012, the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) was the only invertebrate protected under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.[36] In 2012, this legislation was extended to include all cephalopods[37] in accordance with a general EU directive.[38]

Defense

The octopus's primary defense is to hide or to disguise itself through camouflage and mimicry.[39] Octopuses have several secondary defenses (defenses they use once they have been seen by a predator). The most common secondary defense is fast escape. Other defenses include distraction with the use of ink sacs and autotomising limbs.

Most octopuses can eject a thick, blackish ink in a large cloud to aid in escaping from predators. The main coloring agent of the ink is melanin, which is the same chemical that gives humans their hair and skin color. This ink cloud is thought to reduce the efficiency of olfactory organs, which would aid evasion from predators that employ smell for hunting, such as sharks. Ink clouds of some species might serve as pseudomorphs, or decoys that the predator attacks instead.[40]

The octopus's camouflage is aided by certain specialized skin cells which can change the apparent color, opacity, and reflectivity of the epidermis. Chromatophores contain yellow, orange, red, brown, or black pigments; most species have three of these colors, while some have two or four. Other color-changing cells are reflective iridophores, and leucophores (white).[41] This color-changing ability can also be used to communicate with or warn other octopuses. The highly venomous blue-ringed octopus becomes bright yellow with blue rings when it is provoked. Octopuses can use muscles in the skin to change the texture of their mantle to achieve a greater camouflage. In some species, the mantle can take on the spiky appearance of seaweed, or the scraggly, bumpy texture of a rock, among other disguises. However, in some species, skin anatomy is limited to relatively patternless shades of one color, and limited skin texture. It is thought that octopuses that are day-active and/or live in complex habitats such as coral reefs have evolved more complex skin than their nocturnal and/or sand-dwelling relatives.[39]

When under attack, some octopuses can perform arm autotomy, in a manner similar to the way skinks and other lizards detach their tails. The crawling arm serves as a distraction to would-be predators. Such severed arms remain sensitive to stimuli and move away from unpleasant sensations.[42]

A few species, such as the mimic octopus, have a fourth defense mechanism. They can combine their highly flexible bodies with their color-changing ability to accurately mimic other, more dangerous animals, such as lionfish, sea snakes, and eels.[43][44]

Reproduction

When octopuses reproduce, the male uses a specialized arm called a hectocotylus to transfer spermatophores (packets of sperm) from the terminal organ of the reproductive tract (the cephalopod "penis") into the female's mantle cavity.[45] The hectocotylus in benthic octopuses is usually the third right arm. Males die within a few months of mating. In some species, the female octopus can keep the sperm alive inside her for weeks until her eggs are mature. After they have been fertilized, the female lays about 200,000 eggs (this figure dramatically varies between families, genera, species and also individuals).

Cohabitation

Pacific striped octopuses share food and habitation but most other octopuses are solitary outside of mating.[46]

Senses

Octopuses have keen eyesight. Like other cephalopods, they can distinguish the polarization of light. Color vision appears to vary from species to species, being present in O. aegina but absent in O. vulgaris.[47] Attached to the brain are two special organs, called statocysts, that allow the octopus to sense the orientation of its body relative to horizontal. An autonomic response keeps the octopus's eyes oriented so the pupil slit is always horizontal.

Octopuses also have an excellent sense of touch. The octopus's suction cups are equipped with chemoreceptors so the octopus can taste what it is touching. The arms contain tension sensors so the octopus knows whether its arms are stretched out. However, it has a very poor proprioceptive sense. The tension receptors are not sufficient for the brain to determine the position of the octopus's body or arms. (It is not clear whether the octopus brain would be capable of processing the large amount of information that this would require; the flexibility of the octopus's arms is much greater than that of the limbs of vertebrates, which devote large areas of cerebral cortex to the processing of proprioceptive inputs.) As a result, the octopus does not possess stereognosis; that is, it does not form a mental image of the overall shape of the object it is handling. It can detect local texture variations, but cannot integrate the information into a larger picture.[48]

The neurological autonomy of the arms means the octopus has great difficulty learning about the detailed effects of its motions. The brain may issue a high-level command to the arms, but the nerve cords in the arms execute the details. There is no neurological path for the brain to receive proprioceptive feedback about just how its command was executed by the arms; the only way it knows just what motions were made is by observing the arms visually, i.e. exteroception.[48]

Octopuses might use the statocyst (a sac-like structure containing a mineralised mass and sensitive hairs) to register sound. The common octopus can hear sounds between 400 Hz and 1000 Hz, and hears best at a frequency of 600 Hz.[49]

Locomotion

Octopuses move about by crawling or swimming. Their main means of slow travel is crawling, with some swimming. Jet propulsion is their fastest means of locomotion, followed by swimming and walking.[50]

They crawl by walking on their arms, usually on many at once, on both solid and soft surfaces, while supported in water. In 2005, some octopuses (Adopus aculeatus and Amphioctopus marginatus under current taxonomy) were found to walk on two arms, while at the same time resembling plant matter.[51] This form of locomotion allows these octopuses to move quickly away from a potential predator while possibly not triggering that predator's search image for octopus (food).[50] A study of this behavior conducted by the Weymouth Sea Life Centre led to the suggestion that the two rearmost appendages may be more accurately termed "legs" rather than "arms".[52] Some species of octopus can crawl out of the water for a short period, which they may do between tide pools while hunting crustaceans or gastropods or to escape predators.[53][54]

Octopuses swim by expelling a jet of water from a contractile mantle, and aiming it via a muscular siphon.

Diet

Bottom-dwelling octopuses eat mainly crabs, polychaete worms, and other molluscs such as whelks and clams. Open-ocean octopuses eat mainly prawns, fish and other cephalopods. They usually inject their prey with a paralysing saliva before dismembering it into small pieces with their beaks.[55] Octopuses feed on shelled molluscs either by using force, or by drilling a hole in the shell, injecting a secretion into the hole, and then extracting the soft body of the mollusc.[56]

Large octopuses have also been known to catch and kill some species of sharks.[57] Seabirds have also been documented as prey.[58]

Size

The giant Pacific octopus, Enteroctopus dofleini, is often cited as the largest known octopus species. Adults usually weigh around 15 kg (33 lb), with an arm span of up to 4.3 m (14 ft).[59] The largest specimen of this species to be scientifically documented was an animal with a live mass of 71 kg (156.5 lb).[60] The alternative contender is the seven-arm octopus, Haliphron atlanticus, based on a 61 kg (134 lb) carcass estimated to have a live mass of 75 kg (165 lb).[61][62] However, a number of questionable size records would suggest E. dofleini is the largest of all known octopus species by a considerable margin;[63] one such record is of a specimen weighing 272 kg (600 lb) and having an arm span of 9 m (30 ft).[64]

Relationship to humans

Ancient peoples of the Mediterranean were aware of the octopus, as evidenced by certain artworks and designs of prehistory. For example, a stone carving found in the archaeological recovery from Bronze Age Minoan Crete at Knossos (1900 – 1100 BC) has a depiction of a fisherman carrying an octopus.[65]

In classical Greece, Aristotle (384 BC – 322 BC) commented on the colour-changing abilities of the octopus, both for camouflage and for signalling, in his Historia animalium:[66]

The octopus ... seeks its prey by so changing its colour as to render it like the colour of the stones adjacent to it; it does so also when alarmed.— Aristotle[66]

Octopuses were often depicted in the art of the Moche people of ancient Peru, who worshipped the sea and its animals.[67]

In mythology

The Gorgon of Greek mythology has been thought to have been inspired by the octopus or squid, the octopus itself representing the severed head of Medusa, the beak as the protruding tongue and fangs, and its tentacles as the snakes.[68]

The Kraken are legendary sea monsters of giant proportions said to dwell off the coasts of Norway and Greenland, usually portrayed in art as a giant octopus attacking ships.

The Hawaiian creation myth relates that the present cosmos is only the last of a series, having arisen in stages from the wreck of the previous universe. In this account, the octopus is the lone survivor of the previous, alien universe.[69]

Akkorokamui is a gigantic octopus-like monster from Ainu folklore, which supposedly lurks in Funka Bay in Hokkaidō and has been sighted in several locations including Taiwan and Korea since the 19th century.[70]

In Japanese mythology and folklore there is a yokai called the tako no nana ashi, that is an octopus with seven tentacles.

In literature

The octopus has a significant role in Victor Hugo's book Travailleurs de la mer (Toilers of the Sea).[71] Ian Fleming's 1966 short story collection Octopussy and The Living Daylights, and the 1983 James Bond film partly inspired by Hugo's book.

In John Steinbeck's novella Sweet Thursday, the marine biologist "Doc" is studying what the denizens of Cannery Row call "devilfish". Doc's study of octopuses to ascertain whether their behavior displays emotional responses similar to humans, such as apoplexy, is a major plot device in the novella.[72]

Ed Ricketts, the marine biologist who was Steinbeck's friend and inspiration for the character Doc, had an octopus as a trademark for products sold by his Pacific Biological Laboratories.

Ringo Starr wrote a 2014 children's book based on his 1969 song "Octopus's Garden". The book is illustrated by Ben Court.[73]

In popular culture

In Pixar's 2016 film Finding Dory, a sequel to its highly successful 2003 Finding Nemo, Hank the octopus plays a major role in helping Dory find her parents. According to Pixar personnel, the character is based on a mimic octopus.[74]

As a metaphor

Due to having numerous arms that emanate from a common center, the octopus is often used as a metaphor for a group or organization that is perceived as being powerful, manipulative or bent on domination. Use of this terminology is invariably negative and employed by the opponents of the groups or institutions so described.[75]

As food

Octopus is eaten in many cultures. They are a common food in Mediterranean and Asian sea areas.[76][77] The arms and sometimes other body parts are prepared in various ways, often varying by species or geography.

Live octopuses are eaten in several countries around the world, including the US.[78][79] Animal welfare groups have objected to this practice on the basis that octopuses can experience pain.[80] In support of this, since September 2010, octopuses being used for scientific purposes in the EU are protected by EU Directive 2010/63/EU which states "...there is scientific evidence of their [cephalopods] ability to experience pain, suffering, distress and lasting harm.[38] In the UK, this means that octopuses used for scientific purposes must be killed humanely, according to prescribed methods (known as "Schedule 1 methods of euthanasia").[81]

As pets

Though octopuses can be difficult to keep in captivity, some people keep them as pets. They often escape even from supposedly secure tanks, due to their problem-solving skills, mobility and lack of rigid structure.

The variation in size and lifespan among octopus species makes it difficult to know how long a new specimen can naturally be expected to live. That is, a small octopus may be just born or may be an adult, depending on its species. By selecting a well-known species, such as the California two-spot octopus, one can choose a small octopus (around the size of a tennis ball) and be confident it is young with a full life ahead of it.

Classification

| Wikispecies has information related to: Octopoda |

Cephalopods have existed for around 500 million years, although octopus ancestors were in the Carboniferous seas around 300 million years ago. The oldest octopus fossil, Pohlsepia, can be found at the Field Museum in Chicago.[82]

- Class Cephalopoda

- Subclass Nautiloidea: nautilus

- Subclass Coleoidea

- Superorder Decapodiformes: squid, cuttlefish

- Superorder Octopodiformes

- Family †Trachyteuthididae (incertae sedis)

- Order Vampyromorphida: vampire squid

- Order Octopoda

- Genus †Keuppia (incertae sedis)

- Genus †Palaeoctopus (incertae sedis)

- Genus †Paleocirroteuthis (incertae sedis)

- Genus †Pohlsepia (incertae sedis)

- Genus †Proteroctopus (incertae sedis)

- Genus †Styletoctopus (incertae sedis)

- Suborder Cirrina: finned deep-sea octopus

- Family Opisthoteuthidae: umbrella octopus

- Family Cirroctopodidae

- Family Cirroteuthidae

- Family Stauroteuthidae

- Suborder Incirrina

- Superfamily Octopodoidea

- Family Amphitretidae: telescope octopus

- Family Bolitaenidae: gelatinous octopus

- Family Octopodidae: benthic octopus

- Genus Enteroctopus: giant octopus

- Genus Octopus

- Family Vitreledonellidae: glass octopus

- Superfamily Argonautoidea

- Family Alloposidae: seven-arm octopus

- Family Argonautidae: argonauts

- Family Ocythoidae: tuberculate pelagic octopus

- Family Tremoctopodidae: blanket octopus

- Superfamily Octopodoidea

See also

- Henry the Hexapus, a six-armed octopus

- Legend of the Octopus

- Octopus wrestling

- Paralarva

- Paul the Octopus, famous for predicting football results in the 2010 FIFA World Cup

References

- ↑ "ITIS Report: Octopoda Leach, 1818". Itis.gov. 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ "Coleoidea – Recent cephalopods". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

- ↑ Semmens (2004). "Understanding octopus growth: patterns, variability and physiology". Marine and Freshwater Research. 55: 367. doi:10.1071/MF03155.

- ↑ "Facts About Octopuses". Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Tentacles of venom: new study reveals all octopuses are venomous". University of Melbourne. 15 April 2009.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ "Octopus". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "ὀκτώπους". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- 1 2 "Octopus". Oxforddictionaries.com. 2014-01-30. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Michel, Jean-Baptiste; Shen, Yuan; Aiden, Aviva; Veres, Adrian; Gray, Matthew; Pickett, Joseph; Hoiberg, Dale; Clancy, Dan; Norvig, Peter; Orwant, Jon; Pinker, Steven; Nowak, Martin; The Google Books Team (14 January 2011). "Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books". Science. 331 (6014): 176–182. doi:10.1126/science.1199644. PMC 3279742

. PMID 21163965. Relevant data at Google Ngram Viewer.

. PMID 21163965. Relevant data at Google Ngram Viewer. - ↑ Peters, Pam (2004). The Cambridge Guide to English Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62181-X, p. 388.

- ↑ Fowler's Modern English Usage states that the only acceptable plural in English is "octopuses", that "octopi" is misconceived, and "octopodes" pedantic.

- ↑ Chambers 21st Century Dictionary (retrieved 19 October 2007)

- ↑ Kory Stamper. Ask the editor: octopus. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ OED.com (subscription required). Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ "centipede". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Stevenson, Angus; Lindberg, Christine A., eds. (2010). New Oxford American Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195392883.

- ↑ Norman, M. 2000. Cephalopods: A World Guide. ConchBooks, Hackenheim. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-925919-32-9 "There is some confusion around the terms arms versus tentacles. The numerous limbs of nautiluses are called tentacles. The ring of eight limbs around the mouth in cuttlefish, squids and octopuses are called arms. Cuttlefish and squid also have a pair of specialized limbs attached between the bases of the third and fourth arm pairs [...]. These are known as feeding tentacles and are used to shoot out and grab prey."

- ↑ Wodinsky, Jerome (2 December 1977). "Hormonal Inhibition of Feeding and Death in Octopus: Control by Optic Gland Secretion". Science. 198 (4320): 948–951. doi:10.1126/science.198.4320.948. PMID 17787564. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Garry. "What is this octopus thinking?". Archived from the original on 7 April 2012.

- 1 2 Stewart, Doug (1997). "Armed but not dangerous: Is the octopus really the invertebrate intellect of the sea". National Wildlife. 35 (2). URL is not the source.

- 1 2 "Giant Octopus – Mighty but Secretive Denizen of the Deep". Web.archive.org. 2008-01-02. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (23 June 2008). "How Smart is the Octopus?". Slate.com.

- ↑ "Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual" (PDF). AZA (Association of Zoos and Aquariums) Aquatic Invertebrate Taxonomic Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA Animal Welfare Committee. 2014-09-09. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- ↑ Yekutieli, Y.; Sagiv-Zohar, R.; Aharonov, R.; Engel, Y.; Hochner, B.; Flash, T. (August 2005). "Dynamic model of the octopus arm. I. Biomechanics of the octopus reaching movement". J. Neurophysiol. 94 (2): 1443–58. doi:10.1152/jn.00684.2004. PMID 15829594.

- ↑ Zullo, L.; Sumbre, G.; Agnisola, C.; Flash, T.; Hochner, B. (October 2009). "Nonsomatotopic organization of the higher motor centers in octopus". Curr. Biol. 19 (19): 1632–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.067. PMID 19765993.

- ↑ Greenfieldboyce, Nell (15 May 2014). "Why This Octopus Isn't Stuck-Up". NPR.org.

- ↑ "Octopus intelligence: Jar opening". BBC News. 2003-02-25. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Mather, J. A.; Anderson, R. C. (1998). Wood, J. B., ed. "What behavior can we expect of octopuses?". The Cephalopod Page.

- ↑ Wood, James B.; Anderson, Roland C. (2004). "Interspecific Evaluation of Octopus Escape Behavior" (PDF). Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 7 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1207/s15327604jaws0702_2. PMID 15234886. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ↑ Lee, Henry (1875). "V: The octopus out of water". Aquarium Notes – The Octopus; or, the "devil-fish" of fiction and of fact. London: Chapman and Hall. pp. 38–39. OCLC 1544491. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

The marauding rascal had occasionally issued from the water in his tank, and clambered up the rocks, and over the wall into the next one; there he had helped himself to a young lump-fish, and, having devoured it, returned demurely to his own quarters by the same route, with well-filled stomach and contented mind.

- ↑ Roy, Eleanor Ainge (14 April 2016). "The great escape: Inky the octopus legs it to freedom from aquarium". The Guardian (Australia).

- ↑ Morelle, Rebecca (2009-12-14). "Octopus snatches coconut and runs". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ↑ "Coconut shelter: evidence of tool use by octopuses". EduTube Educational Videos. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Finn, J. K.; Tregenza, T; Norman, M. D. (2009). "Defensive tool use in a coconut-carrying octopus". Current Biology. 19 (23): R1069–70. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.052. PMID 20064403.

- ↑ "The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (Amendment) Order 1993". The National Archives. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ "The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 Amendment Regulations 2012". The National Archives. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council". Article 1, 3(b) (see page 276/39): Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- 1 2 Hanlon, R.T. & J.B. Messenger 1996. Cephalopod Behaviour. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- ↑ Caldwell, R. L. (2005). "An Observation of Inking Behavior Protecting Adult Octopus bocki from Predation by Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) Hatchlings". Pacific Science. 59 (1): 69–72. doi:10.1353/psc.2005.0004.

- ↑ Meyers, Nadia. "Tales from the Cryptic: The Common Atlantic Octopus". Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

- ↑ Harmon, Katherine (27 August 2013). "Even Severed Octopus Arms Have Smart Moves". Octopus Chronicles. Scientific American.

- ↑ Norman, MD; Finn, J; Tregenza, T (September 2001). "Dynamic mimicry in an Indo-Malayan octopus" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society. 268 (1478): 1755–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1708. PMC 1088805

. PMID 11522192.

. PMID 11522192. - ↑ Norman, M.D. (2005). "The "Mimic Octopus" (Thaumoctopus mimicus n. gen. et sp.), a new octopus from the tropical Indo-West Pacific (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae)". Molluscan Research. 25 (2): 57–70.

- ↑ Young, R.E., M. Vecchione & K.M. Mangold 1999. Cephalopoda Glossary. Tree of Life web project.

- ↑ Edmonds, Patricia (April 2016). "What's Odd About That Octopus? It's Mating Beak to Beak". National Geographic.

- ↑ Kawamura, G.; et al. (2001). "Color Discrimination Conditioning in Two Octopus Octopus aegina and O. vulgaris" (PDF). Nippon Suisan Gakkashi. 67 (1): 35–39. doi:10.2331/suisan.67.35.

- 1 2 Wells. Martin John. Octopus: physiology and behaviour of an advanced invertebrate. London : Chapman and Hall; New York : distributed in the U.S.A. by Halsted Press, 1978.

- ↑ Walker, Matt (15 June 2009). "The cephalopods can hear you". BBC. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- 1 2 Huffard, Christine L. (2006). "Locomotion by Abdopus aculeatus (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae): walking the line between primary and secondary defenses". Journal of Experimental Biology. 209: 3697–3707. doi:10.1242/jeb.02435. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Huffard, C. L.; Boneka, F; Full, RJ (2005). "Underwater Bipedal Locomotion by Octopuses in Disguise". Science. 307 (5717): 1927. doi:10.1126/science.1109616. PMID 15790846.

- ↑ Octopuses have only six arms, the other two are actually legs! Hindustan Times, 13 August 2008.

- ↑ Harmon, Katherine (24 November 2011). "Land-Walking Octopus Explained". Octopus Chronicles. Scientific American. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ Wood, James B.; Anderson, Roland C. (2004). "Interspecific Evaluation of Octopus Escape Behavior" (PDF). Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. 7 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1207/s15327604jaws0702_2. PMID 15234886.

- ↑ Wassilieff, Maggy; and O’Shea, Steve (2009) "Octopus and squid – Feeding and predation" Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2 March 2009.

- ↑ Wodinsky, Jerome (1969). "Penetration of the Shell and Feeding on Gastropods by Octopus". Am. Zool. 9 (3): 997–1010. doi:10.1093/icb/9.3.997.

- ↑ Archived Google video of an octopus catching a shark, from The Octopus Show by Mike deGruy Archived February 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Octopus Eats Seagull, Woman Becomes Famous – Shaw TV Victoria on YouTube

- ↑ "Smithsonian National Zoological Park: Giant Pacific Octopus". Nationalzoo.si.edu. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Cosgrove, J.A. 1987. Aspects of the Natural History of Octopus dofleini, the Giant Pacific Octopus. M.Sc. Thesis. Department of Biology, University of Victoria (Canada), 101 pp.

- ↑ O'Shea, S. (2004). "The giant octopus Haliphron atlanticus (Mollusca : Octopoda) in New Zealand waters". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 31 (1): 7–13. doi:10.1080/03014223.2004.9518353.

- ↑ O'Shea, S. (2002). "Haliphron atlanticus – a giant gelatinous octopus" (PDF). Biodiversity Update. 5: 1.

- ↑ Norman, M. 2000. Cephalopods: A World Guide. ConchBooks, Hackenheim. p. 214.

- ↑ High, William L. (1976). "The giant Pacific octopus" (PDF). Marine Fisheries Review. U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service. 38 (9): 17–22.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. 2007 Knossos fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian

- 1 2 Aristotle (c. 350 BC). Historia Animalium. IX, 622a: 2–10. Cited in Borrelli, Luciana; Gherardi, Francesca; Fiorito, Graziano (2006). A catalogue of body patterning in Cephalopoda. Firenze University Press. ISBN 978-88-8453-377-7. Abstract

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 199 7.

- ↑ Wilk, Stephen R. (2000). Medusa:Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019988773X.

- ↑ Dixon, Roland Burrage (1916). Oceanic [mythology]. 9. Marshall Jones Company. pp. 2–.

- ↑ Swancer, Brent via Coleman, Loren. Akkorokamui. Cryptomundo. http://www.cryptomundo.com/cryptozoo-news/akkorokamui

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Octopus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Octopus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ "Sweet Thursday – Plot Synopsis". Steinbeck in the Schools. San José State University. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Starr, Ringo; Cort, Bud. "Octopus's Garden". Simon & Schuster. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Giardina, Carolyn (17 June 2016), 'Finding Dory:' How "Reluctant Superhero" Hank the Octopus Made it to the Screen, retrieved 5 August 2016

- ↑ Palmer, Jessica (2010-05-30). "Nazi Tentacles: The octopus as visual metaphor". Scienceblogs.com. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ "Common octopus". Animal fact guide.

- ↑ "Giant Pacific octopus". Monterey Bay Aquarium.

- ↑ Eriksen, L. (November 10, 2010). "Live and let dine". The Guardian. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ↑ Killingsworth, Silvia (October 3, 2014). "Why not eat octopus?". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ↑ Ferrier, M. (May 30, 2010). "Macho foodies in New York develop a taste for notoriety". Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ↑ "The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 Amendment Regulations 2012". Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ↑ Courage, Katherine Harmon (2013). Octopus!. USA: The Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-59184-527-0.

External links

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Octopoda |

- The Cephalopod Page

- TONMO.COM – The Octopus News Magazine Online

- Tree of Life website: information about cephalopods along with pictures and videos

- Discussion about the plural

- An octopus's shark encounter – footage of an octopus eating a shark (also in QuickTime format)

- Camouflage in action

- Video showing an Octopus escaping through a 1-inch (25 mm) hole

- Bipedal Octopuses- Video, Information, Original paper

- "Why Cephalopods Change Color" (PDF). (359 KB)

- Video of walking octopuses

- What Lurks Beneath: 2015 giant octopus novel

.png)