Mystic, Connecticut

| Mystic | |

|---|---|

| Census-designated place | |

|

Main Street, downtown Mystic | |

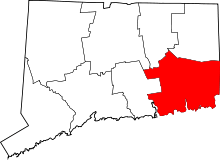

Mystic Location within the state of Connecticut | |

| Coordinates: 41°21′20″N 71°57′50″W / 41.35556°N 71.96389°WCoordinates: 41°21′20″N 71°57′50″W / 41.35556°N 71.96389°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Connecticut |

| County | New London |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.8 sq mi (9.8 km2) |

| • Land | 3.4 sq mi (8.7 km2) |

| • Water | 0.4 sq mi (1.1 km2) |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 4,205 |

| • Density | 1,100/sq mi (430/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC−5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−4) |

| ZIP codes | 06355, 06372, 06388 |

| Area code Exchanges: 245, 536, 572. | 860 |

| FIPS code | 09-49810 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0209165 |

Mystic is a village and census-designated place (CDP) in New London County, Connecticut, in the United States. The population was 4,205 at the 2010 census.[1] Mystic has no independent government because it is not a legally recognized municipality in the state of Connecticut. Rather, Mystic is located within the towns of Groton (west of the Mystic River, and also known as West Mystic) and Stonington (east of the Mystic River).

Historically, Mystic was a leading seaport of the area, and the story of Mystic's nautical connection is told at Mystic Seaport, the nation's largest maritime museum, which has preserved a number of sailing ships (most notably the whaleship Charles W. Morgan) and seaport buildings. The village is located on the Mystic River, which flows into Long Island Sound, providing access to the sea. The Mystic River Bascule Bridge crosses the river in the center of the village. According to the Mystic River Historical Society, the name "Mystic" is derived from the Pequot term "missi-tuk", describing a large river whose waters are driven into waves by tides or wind.

History

Pre-colonial era

Before the 17th century, the indigenous[2] Pequot people lived in this portion of southeastern Connecticut.

The Pequots built their first village overlooking the western bank of the Mystic River, which they called the Siccanemos. The only written records describe this village as existing in 1637.[3] By that time, the Pequots were in control of a considerable amount of territory, extending toward the Pawcatuck River to the east and the Connecticut River to the west, providing them with full access to the waters. They also had supremacy over some of the most strategically located terrain. To the northwest, the Five Nations of the Iroquois dominated the land linked by the Great Lakes and the Hudson River, allowing trading to occur between the Iroquois Nations and the Dutch. The Pequots were settled just distant enough to be secure from any danger that the Iroquois posed.[3]

Pequot War

In 1632, the Dutch established a trading post at Good Hope, near present-day Armsmear in Hartford, depriving the Pequot of a monopoly in the area. The Dutch post attracted additional traders to the Pequot territory whom the Pequots could not control, raising apprehension between the two villages. This destabilized the Pequots' control of fur and wampum sources. In 1634, hostilities escalated between the Pequot and Narragansett tribes.

The Narragansett passed through or near Pequot territory on their way to the Dutch post, and the Pequot resented the Narragansett's ability to encroach upon their territory to the point that a Pequot band attacked and killed a Narragansett band on its way to trade at Good Hope.[3]

In revenge for this attack, the Dutch captured and seized Tatobem, Pequot's uppermost chief, and held him at ransom to be paid in wampum. The ransom was paid immediately, but Tatobem was executed anyway; they retaliated by killing an Englishman named John Stone at the Connecticut River. There are many assumptions to why Stone was chosen in retribution. Some historians say that, while trading on shore, Stone kidnapped a handful of Pequots with intentions to sell them into slavery, and was beaten and slaughtered by their rescuers.[4]

The Massachusetts Bay colony interpreted the killing of Stone as a declaration of war. In October 1634, Pequot delegates took a trip to Massachusetts Bay to guarantee the colonists that they had not intended nor planned to go to war with the English. They took full blame for Stone's death, and offered Governor Roger Ludlow payment for his death. The Massachusetts Bay colonists refused to accept the payment as justice for Stone's death.

The Massachusetts Bay government "demanded that Stone's killer be handed over to meet European justice, that a ransom in wampum worth 250 pounds sterling be paid; that the Pequot cede all of their land to the Massachusetts Bay Colony; that the Pequot only trade with the English; and that all disputes between the Pequot and the Narragansett be mediated by the English. The Pequot delegation seemed to agree to the settlement and returned home, but Tatobem's successor, Sassacus, rejected and thereby nullified the agreement."[3]

Tensions increased among local Indian tribes, especially towards the Pequot. In 1636, John Oldham was murdered in his boat off Block Island, a trader and friend of the Narragansetts. The murderers were Block Islanders, a branch of Narragansetts; however, they escaped capture and were given safe haven by the Pequots. This outraged the Narragansetts.[4]

In May 1637, captains John Underhill and John Mason led a retaliatory mission through Narragansett land along with their allies, the Narragansetts and Mohegans, and struck the Pequot settlement in Mystic in the event which came to be known as the Mystic massacre. Uncas and Wequash also joined the fight, bringing seventy of his own men. The settlement was decimated. Mason set fire to eighty homes, killing 600–700 Pequots. Seven were taken captive and seven escaped. Two Englishmen were killed, while 20-40 were wounded.[5]

Captain John Underhill, one of the English commanders, documents the event in his journal Newes from America:

Down fell men, women, and children. Those that 'scaped us, fell into the hands of the Indians that were in the rear of us. Not above five of them 'scaped out of our hands. Our Indians came us and greatly admired the manner of Englishmen's fight, but cried "Mach it, mach it!"—that is, "It is naught, it is naught, because it is too furious, and slays too many men." Great and doleful was the bloody sight to the view of young soldiers that never had been in war, to see so many souls lie gasping on the ground, so thick, in some places, that you could hardly pass along.[3]

On September 21, 1638, the colonists signed the Treaty of Hartford, officially ending the Pequot War. It outlawed the name Pequot, forbad the Pequot from regrouping, and required that other Indians in the region submit all their intertribal grievances to the English and abide by their decisions. Gradually, with the help of sympathetic English leaders, the Pequot were able to re-establish their identity, but as separate tribes in separate communities: the Mashantucket (Western) Pequots and the Paucatuck (Eastern) Pequots, the first Indian reservations in America.[4]

English settlement

As a result of the Pequot War, Pequot control of the Mystic area ended and English settlements increased in the area. By the 1640s, Connecticut Colony began to grant land to the Pequot War veterans. John Winthrop the Younger, the son of the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, was among those to receive property, much of which was in southeastern Connecticut. Other early settlers in the Mystic area included Robert Burrows and George Denison, who held land in the Mystic River Valley.[6]

Settlement grew slowly. With the removal of the Pequots, the Narragansetts, led by Miantonomo, claimed some of the former Pequot territory, which had been held by the Mohegans. Tensions increased between the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes, and war broke out between them, resulting in Miantonomo's death and the Mohegans' victory.[5]

The Connecticut government and Massachusetts Bay government began to quarrel over boundaries, thus causing some conflicting claims concerning governmental authority between the Mystic River and the Pawcatuck River. In the 1640s and 1650s, "Connecticut" referred to settlements located along the Connecticut River, as well as its claims in other parts of the region.[7] Massachusetts Bay, however, claimed to have authority over Stonington and even into what is now Rhode Island.

Connecticut did not have a royal charter that separated it from the Massachusetts Bay Colony; the Connecticut General Court was formed by leaders of the settlements. The General Court claimed rule of the area by right of conquest, but the Massachusetts Bay Colony saw matters differently. The Bay Colony had contributed to the war by sending a militia under captains John Underhill and Thomas Stoughton, which would enable them territorial rights.[7] This would have made John Winthrop Jr.'s land answerable to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, as opposed to the Connecticut Court.

With conflicting views, both colonies turned to the United Colonies of New England to resolve the dispute. The United Colonies of New England was formed in 1643, established to settle disputes such as this one. It was voted to create the boundary between the claims of the Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut at the Thames River. As a result, Connecticut would be positioned west of the river, and Massachusetts Bay could have the land to the east, including the Mystic River.[3]

Throughout the next decade, colonists were beginning to settle around the Mystic River. John Mason, one of the captains who led the colonists against the Pequots, had previously been granted 500 acres (2 km2) on the eastern banks of the Mystic River.[8] He also received the island that now bears his name, though he never lived on the property. In 1653, John Gallup, Jr. was given 300 acres (1.2 km2) approximately midway up the east part of the Mystic River.

Within the same year, other settlers joined John Gallup and began to settle around the Mystic River. George Denison, a veteran of Oliver Cromwell's army, was given his own strip of 300 acres (1.2 km2), just south of Gallup's land in 1654. Thomas Miner, who had immigrated to Massachusetts with John Winthrop, was granted many land plots, the main one lying on Quiambaug Cove, just east of the Mystic River.[8] Other families granted land at their arrival were Reverend Robert Blinman, the Beebe brothers, Thomas Parke, and Connecticut Governor John Hayne.

Like Captain John Mason, not all these men actually lived on their land. Many sold it to profit from or employed an overseer to cultivate their property. Many men, however, actually brought their wives and children, which indicated their plans on forming a community in the Mystic River Valley.

There was one recorded case of a woman who did not come to the Mystic River Valley as a wife. Widow Margaret Lake received a grant from the Massachusetts Bay authority and was the only woman to receive a land grant in her own name.[3] Margaret Lake, like many men in her day, also did not live on her land, and hired other people to maintain her property. She ended up taking up residence in what is now called Lakes Pond. Lake's daughter was married to John Gallup, while her sister was married to John Winthrop, Massachusetts Bay Governor.[3]

By 1675, settlement in the Mystic River Valley had grown tremendously, and infrastructure was beginning to appear, as well as an economy. The Pequot Trail was used as a main highway to get around the Mystic River, and played a vital role in the English lives, allowing them to transport livestock, crops, furs, and other equipment to and from their farm lands. However, those families living on the east side of the Mystic River were unable to make any use of the Pequot Trail, like Miner and Mason, and desired the creation of a bridge to connect the two. As early as 1660, Robert Burrows was given authorization to institute a ferry somewhere along the middle of the river's length. This earned his home the name of "Half-way House".[6]

The Pequot Trail also connected the settlers to their church. In the beginning, there were issues of Stonington residents attending their church. This led to the creation of their own church. The town of Stonington was then established as separate from Mystic in regards to church attendance, and was granted leave to build one of their own. The building became known as the Road Church.[6] As the religious community around the Mystic River diversified and grew, new churches were allowed to be built near the river.

In 1679, schooling systems emerged, and John Fish became the first schoolmaster in Stonington, conducting classes and lessons in his home.[3] Education was a very important thing to the New England colonists, even allowing girls, African Americans, Indians, and servants to learn basic literacy skills. Most families throughout New England had six or more children in each household, giving Fish plenty of students.

Fish also gave lectures and insights about marriage and maintenance of a solid family. Divorce was very uncommon in those days; however, John Fish's wife ran off with Samuel Culver. In the case of a runaway spouse, the abandoned spouse was not allowed to file for divorce until six years had passed. This law ensured that the spouse was actually gone and not intending to come back.[3] Fish was eventually allowed to divorce in 1680, but this had no impact on his reputation as a school teacher, and parents continued to allow their children to attend his classes.

18th century

By the first decade of the 18th century, three villages had begun to develop along the Mystic River. The largest village was called Mystic (now Old Mystic), also known as the Head of the River because it lay where several creeks united into the Mystic River estuary.[6] Two villages lay farther down the river. One was called Stonington and was considered to be Lower Mystic, consisting of twelve houses by the early 19th century. These twelve houses lay along Willow Street, which ended at the ferry landing. On the opposite bank of the river in the town of Groton stood the village that became known as Portersville.[3]

Through the 18th century, Mystic's economy was composed of manufacturing, road building, and maritime trades. Agriculture was the main component of their economy, since most of the citizens were farmers. In turn, the colonists provided their mother country with raw material resources that led to the emergence of a colonial manufacturing system. Land remained an essential source of wealth, though some land was very rocky and prevented early farmers from producing crops. This, however, did not necessarily lead to poverty. They grew corn, wheat, peas, potatoes, and a variety of fruits. They raised cattle, chicken, pigs, and sheep. They were hunters and fishermen and were generally able to sustain themselves. With an average household of about nine children, labor was easily provided in the fields.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 3.8 square miles (9.8 km2), of which 3.3 square miles (8.5 km2) is land and 0.4 square miles (1.0 km2), or 11.61%, is water. The village is on the east and west bank of the estuary of the Mystic River. Mason's Island (Pequot language: Chippachaug) fills the south end of the estuary.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1990 | 2,618 | — | |

| 2000 | 4,001 | 52.8% | |

| 2010 | 4,205 | 5.1% | |

As of the census[9] of 2000, there were 4,001 people, 1,797 households, and 995 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 1,192.7 people per square mile (461.1/km2). There were 1,988 housing units at an average density of 592.6 per square mile (229.1/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 95.8% White, 0.8% African American, 0.4% American Indian, 1.3% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander (i.e. 1 person), 0.3% from other races, and 1.30% from two or more races.[10]

There were 1,797 households out of which 20.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.6% were married couples living together, 7.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.6% were non-families. 35.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.10 and the average family size was 2.76.

In the CDP the age distribution of the population shows 16.7% under the age of 18, 5.4% from 18 to 24, 31.1% from 25 to 44, 27.4% from 45 to 64, and 19.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females there were 92.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.1 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $62,236, and the median income for a family was $70,625. Males had a median income of $50,036 versus $32,400 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $33,376. About 1.6% of families and 3.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 1.9% of those under age 18 and 5.9% of those age 65 or over.

Tourism

The village is a major New England tourist destination. It is home to the Mystic Aquarium & Institute for Exploration, known for its research department, concern with marine life rehabilitation, and its popular beluga whales. The business district contains many restaurants on either side of the bascule bridge where U.S. Route 1 crosses the Mystic River. Local sailing cruises are available on the traditional sailing ship Argia. Short day tours and longer evening cruises are available on the 1908 steamer Sabino departing Mystic Seaport.

Mystic Seaport is the nation's leading maritime museum and one of the premier maritime museums in the world, founded in 1929. It is the home of four National Historic Landmark vessels, including the 1841 whaleship Charles W. Morgan, the oldest merchant vessel in the country. The museum's collections and exhibits include over 500 historic watercraft, a major research library, a large gallery of maritime art, a unique diorama displaying the town of Mystic as it was in the 19th century, a ship restoration shipyard, the Treworgy Planetarium, and a recreation of a 19th-century seafaring village.

The 2013 Moondance International Film Festival was held in Mystic.

Transportation

Amtrak stops at the Mystic station. Bus service is provided by Southeast Area Transit.

In popular culture

The Mystic Pizza restaurant inspired the name of the 1988 film, though it was not the location of the restaurant in the film. Scenes in Mystic Pizza were shot in Mystic, the planetarium at Mystic Seaport, Stonington, Noank, and Watch Hill, Rhode Island.

In 1997, Steven Spielberg shot various scenes for the film Amistad at Mystic Seaport.

Hans Hartman's 2005 low-budget horror film Crippled Creek was shot entirely in Mystic. The story is loosely based on actual events about a group of friends who went missing after going camping locally.

One commercial was filmed in 2005 at Mystic Seaport for FedEx. It was based on the lobstering business in New England. The commercial was aired in the Orange Bowl.

Andy Bernard on the T.V. show The Office mentioned that Mystic was home to a non-profit organization known as The Barnacle Project.

Mystic, Connecticut is mentioned at 9 minutes and 40 seconds into The Firesign Theatre comedy album Don't Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me the Pliers.

The character Dwight Towers is from Mystic in Nevil Shute's nuclear apocalyptic novel On the Beach.

Mystic Seaport is mentioned in popular song Walcott from Vampire Weekend's self-titled album released in January 2008.

National Register of Historic Places

Mystic has three historic districts: the Mystic Bridge Historic District (around U.S. Route 1 and Route 27), Rossie Velvet Mill Historic District (between Pleasant Street and Bruggerman Place) and the Mystic River Historic District (around U.S. Route 1 and Route 215).

Other historic sites/objects in Mystic are:

- Joseph Conrad (ship): Mystic Seaport (added 1947)

- Charles W. Morgan (ship): Mystic Seaport (added December 13, 1966)

- Emma C. Berry (fishing sloop): Greenmanville Avenue (added November 12, 1994)

- L. A. Dunton (ship): Mystic Seaport Museum (added December 4, 1993)

- Pequotsepos Manor: Pequotsepos Rd. (added July 15, 1979)

- Sabino (steamer): Mystic Seaport Museum (added November 5, 1992)

Notable people

- Mary Jobe Akeley, naturalist[11]

- Jason Filardi, screenwriter

- Matt Harvey, New York Mets pitcher

- Sam Lacy, sportswriter

- Stephen Macht, actor

- William Ledyard Stark, Nebraska politician

References

- ↑ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Mystic CDP, Connecticut". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ↑ For many years, historians believed that they migrated in the 16th century from eastern New York. Newer archaeological evidence shows the presence of a people who lived in an area called Gungywump, somewhat northwest of the Mystic River, which suggests that the Pequots may have been indigenous to southeastern Connecticut prior to the 16th century. (Leigh Fought, 2007. A History of Mystic, Connecticut: From Pequot Village to Tourist Town p. 13).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Leigh Fought, A History of Mystic Connecticut: From Pequot Village to Tourist Town. Charleston, North Carolina: www.historypress.net, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "1637 – The Pequot War" (2007). The Society of Colonial War in the State of Connecticut. Accessed November 11, 2008.

- 1 2 The Pequot War. http://www.dowdgen.com/dowd/document/pequots.html (accessed October 12, 2008).

- 1 2 3 4 Mystic: An American Journey. Mystic: Mystic River Historical Society, 2004.

- 1 2 Mystic River Historical Society. Images of America: Mystic. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

- 1 2 Mystic River Historical Society. http://mystichistory.org/about_mrhs.htm (accessed November 13, 2008).

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau

- ↑ "Mary Jobe Akeley". Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

Bibliography

- Fought, Leigh (2007). A History of Mystic Connecticut: From Pequot Village to Tourist Town. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 1-59629-221-0. OCLC 174134160.

- Mystic River Historical Society (2004). Mystic. Images of America Series. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Arcadia Publishing SC. ISBN 978-0-7385-3498-5. OCLC 54816732.

- Wagner, David R.; Jack Dempsey (2004). Mystic Fiasco: How the Indians Won the Pequot War. Scituate, Massachusetts: Digital Scanning. ISBN 1-58218-775-4. OCLC 57182231.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mystic, Connecticut. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mystic, Connecticut. |

- Mystic Aquarium & Institute for Exploration

- Mystic Seaport

- Mystic River Historical Society

- Greater Mystic Chamber of Commerce