Ricketts Glen State Park

| Ricketts Glen State Park | |

| Pennsylvania State Park | |

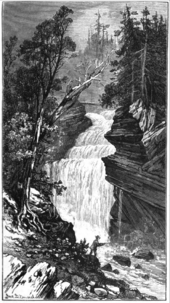

Harrison Wright Falls, 27 feet (8.2 m), at Ricketts Glen State Park | |

| Named for: Robert Bruce Ricketts | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| State | Pennsylvania |

| Counties | Columbia, Luzerne, Sullivan |

| Townships | Sugarloaf, Fairmount, Ross, Colley, Davidson |

| Elevation | 2,198 ft (670 m) [1] |

| Coordinates | 41°19′34″N 76°16′46″W / 41.32611°N 76.27944°WCoordinates: 41°19′34″N 76°16′46″W / 41.32611°N 76.27944°W |

| Area | 13,046.54 acres (5,279.75 ha) [2] |

| Founded | 1942 [3] |

| Management | Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources |

| Visitation | 500,000 [4] |

| IUCN category | V - Protected Landscape/Seascape [5] |

|

Location of Ricketts Glen State Park in Pennsylvania | |

| Website: Ricketts Glen State Park | |

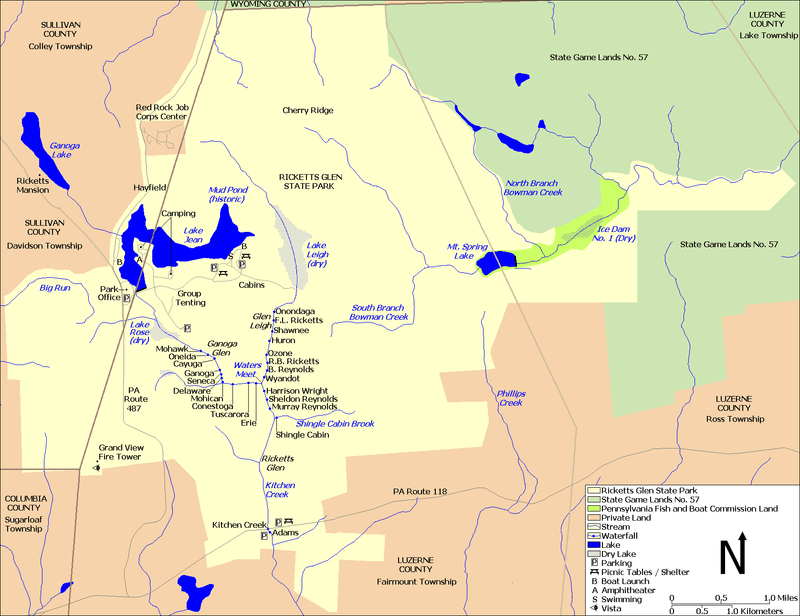

Ricketts Glen State Park is a Pennsylvania state park on 13,050 acres (5,280 ha) in Columbia, Luzerne, and Sullivan counties in Pennsylvania in the United States. Ricketts Glen is a National Natural Landmark known for its old-growth forest and 24 named waterfalls along Kitchen Creek, which flows down the Allegheny Front escarpment from the Allegheny Plateau to the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians. The park is near the borough of Benton on Pennsylvania Route 118 and Pennsylvania Route 487, and is in five townships: Sugarloaf in Columbia County, Fairmount and Ross in Luzerne County, and Colley and Davidson in Sullivan County.

Ricketts Glen's land was once home to Native Americans. From 1822 to 1827, a turnpike was built along the course of PA 487 in what is now the park, where two squatters harvested cherry trees to make bed frames from about 1830 to 1860. The park's waterfalls were one of the main attractions for a hotel from 1873 to 1903; the park is named for the hotel's proprietor, R. Bruce Ricketts, who built the trail along the waterfalls. By the 1890s Ricketts owned or controlled over 80,000 acres (320 km2; 120 sq mi) and made his fortune clearcutting almost all of that land, including much of what is now the park; however he preserved about 2,000 acres (810 ha) of virgin forest in the creek's three glens. The sawmill was at the village of Ricketts, which was mostly north of the park. After his death in 1918, Ricketts' heirs began selling land to the state for Pennsylvania State Game Lands.

Plans to make Ricketts Glen a national park in the 1930s were ended by budget issues and the Second World War; Pennsylvania began purchasing the land in 1942 and fully opened Ricketts Glen State Park in 1944. The Benton Air Force Station, a Cold War radar installation in the park, operated from 1951 to 1975 and still serves as airport radar for nearby Wilkes-Barre and as the Red Rock Job Corps Center. Improvements since the creation of the state park include a new dam for the 245-acre (99 ha) Lake Jean, the breaching of two other dams Ricketts built, trail modifications, and a fire tower. In 1999 Hurricane Floyd briefly closed the park and downed thousands of trees; helicopter logging protected the ecosystem while harvesting lumber worth nearly $7 million, some of which paid for a new park office in 2001.

The park offers hiking, ten cabins, camping (one of the two camping areas is on a peninsula in the lake), horseback riding, and hunting. Lake Jean is used for swimming, fishing, canoeing and kayaking. In winter there is cross-country skiing, ice fishing on the lake, and ice climbing on the frozen falls. The Glens Natural Area has eight named waterfalls in Glen Leigh and ten in Ganoga Glen, these come together at Waters Meet; downstream in Ricketts Glen there are four to six named waterfalls. The park has four rock formations from the Devonian and Carboniferous periods, and is home to a wide variety of plants and animals. It was named an Important Bird Area by the Pennsylvania Audubon Society and is an Important Mammal Area too. Ricketts Glen State Park was chosen by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) and its Bureau of State Parks as one of "25 Must-See Pennsylvania State Parks".[6]

History

Native Americans

Ricketts Glen State Park is in Pennsylvania, where humans have lived since at least 10000 BC. The first settlers in the state were Paleo-Indian nomadic hunters known from their stone tools.[7][8] The hunter-gatherers of the Archaic period, which lasted locally from 7000 to 1000 BC, used a greater variety of more sophisticated stone artifacts. The Woodland period marked the gradual transition to semi-permanent villages and horticulture, between 1000 BC and 1500 AD. Archeological evidence found in the state from this time includes a range of pottery types and styles, burial mounds, pipes, bows and arrows, and ornaments.[7]

The park is in the Susquehanna River drainage basin, the earliest recorded inhabitants of which were the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannocks. They were a matriarchal society that lived in stockaded villages of large longhouses, but their numbers were greatly reduced by disease and warfare with the Five Nations of the Iroquois, and by 1675 they had died out, moved away, or been assimilated into other tribes.[8][9]

After the demise of the Susquehannocks, the lands of the Susquehanna River valley were under the nominal control of the Iroquois, who also lived in longhouses, primarily in what is now the state of New York. The Iroquois had a strong confederacy which gave them power beyond their numbers.[8][10] To fill the void left by the demise of the Susquehannocks, the Iroquois encouraged displaced tribes from the east to settle in the Susquehanna watershed, including the Shawnee and Lenape (or Delaware).[8][9]

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) and subsequent colonial expansion encouraged the migration of many Native Americans westward to the Ohio River basin.[8] On November 5, 1768, the British acquired land, known in Pennsylvania as the New Purchase, from the Iroquois in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix; this included what is now Ricketts Glen State Park.[11] After the American Revolutionary War, Native Americans almost entirely left Pennsylvania.[12] About 1890 a Native American pot, decorated in the style of "the peoples of the Susquehanna region", was found under a rock ledge on Kitchen Creek by Murray Reynolds, for whom a waterfall is named.[13]

Early European inhabitants

Ricketts Glen State Park is in five townships in three counties. After the 1768 purchase, the land became part of Northumberland County, but was soon divided among other counties. Most of the park is in Luzerne County, which was formed in 1786 from part of Northumberland County. Within Luzerne County, the majority of the park, including all of the waterfalls and most of Lake Jean, is in Fairmount Township, which was settled in 1792 and incorporated in 1834; the easternmost part of the park is in Ross Township, which was settled in 1795 and incorporated in 1842.[15] The northwest part of the park is in Sullivan County, which was formed in 1847 from Lycoming County; Davidson Township was settled by 1808 and incorporated in 1833, while Colley Township, which has the park office and part of Lake Jean, was settled in the early 19th century and incorporated in 1849.[16][17] A small part of the southwest part of the park is in Sugarloaf Township in Columbia County; the township was settled in 1792 and incorporated in 1812, the next year Columbia County was formed from Northumberland County.[18][19]

A hunter named Robinson was the first inhabitant in the area whose name is known; around 1800 he had a cabin on the shores of Long Pond (now called Lake Ganoga), which is less than 0.4 miles (0.6 km) northwest of the park. The first development within the park was the construction of the Susquehanna and Tioga Turnpike, which was built from 1822 to 1827 between the Pennsylvania communities of Berwick in the south and Towanda in the north. The turnpike, which Pennsylvania Route 487 mostly follows through the park, had daily stagecoach service from 1827 to 1851; the northbound stagecoach left Berwick in the morning and stopped for lunch at the Long Pond Tavern on the lake about noon.[17][20][21]

The earliest settlers in what became the park were two squatters who built sawmills to make bed frames from cherry trees they cut for lumber. One squatter, Jesse Dodson, cut trees from around 1830 to 1860 and built a mill and the dam for what became Lake Rose in 1842. Dodson also built a dam south of Mud Pond, near what became Lake Jean; both dams were on the Ganoga Glen branch of Kitchen Creek, and each was used to make a "log splash pond".[22][23] The other squatter, named Sickler, also built a mill and log dam, at what became Lake Leigh on the Glen Leigh branch of Kitchen Creek. Sickler was active from 1838 to about 1860.[20][22]

In 1865, a well was drilled at the Dodson mill site, after a Mr. Hadley fraudulently added oil to springs in what became the park. Hadley, who had hoped that investors would think petroleum was present, got the Wheeler & Wilson sewing machine company to invest $40,000 ($620,000 in 2016) in his scheme. In the next two years they drilled two wells, one 2,100 feet (640 m) deep at the former Dodson sawmill at Lake Rose and the other 1,900 feet (580 m) deep near the Ricketts mansion. No oil was ever found, and Hadley eventually fled to Canada.[20][24][25]

R. Bruce Ricketts

While on a hunting trip on Loyalsock Creek north of the park in 1850, brothers Elijah and Clemuel Ricketts were frustrated at having to spend the night on a hotel's parlor floor. In 1851 or 1853 they bought 5,000 acres (2,000 ha), including what is now Lake Ganoga and some of the park, as their own hunting preserve, and built a stone house on the lake shore by 1852 or 1855.[a] The stone house served as their lodge and as a tavern; it was known as "Ricketts Folly" for its isolated location in the wilderness. Clemuel died in 1858 and Elijah bought his share of the land and house. The Ricketts family was not aware of the glens and their waterfalls until about 1865, when they were discovered by two guests from the stone house who went fishing and wandered down Kitchen Creek.[17][20]

Elijah's son Robert Bruce Ricketts, for whom the park is named, joined the Union Army as a private at the outbreak of the American Civil War and rose through the ranks to become a colonel in the artillery. After the war, R. Bruce Ricketts returned to Pennsylvania and in 1869 began purchasing the land around the lake from his father. By 1873 he controlled or owned 66,000 acres (27,000 ha), and eventually this grew to more than 80,000 acres (32,000 ha), including the glens and waterfalls and most of the park.[3][17][20]

While the stone house had served as a home and inn since its construction, in 1872 R. Bruce Ricketts built a three-story wooden addition north of the house. The addition used lumber from a sawmill Ricketts and his partners operated from 1872 to 1875, about 0.5 miles (0.8 km) southeast of the stone house. The North Mountain House hotel opened in 1873; Ricketts' brother Frank, for whom a park waterfall is named, managed it from then until 1898. Many of the hotel's guests were Ricketts' friends and relations, who arrived after school let out in June and stayed all summer until school resumed in September. In 1876 and 1877, Ricketts ran the first summer school in the United States at his house and hotel; one of the teachers was Joseph Rothrock, later known as the "Father of Forestry" in Pennsylvania.[17][20][26]

The waterfalls and Ganoga Lake were the hotel's biggest attractions. By 1875 Ricketts had named the tallest waterfall Ganoga Falls; he eventually named 22 of the waterfalls. Ricketts gave most of them Native American names, and named others for relatives and friends.[17][20][27][28] Ricketts renamed Long Pond as Ganoga Lake in 1881. The name Ganoga was suggested by Pennsylvania senator Charles R. Buckalew; it is an Iroquoian word which Buckalew said meant "water on the mountain" in the Seneca language.[17] Donehoo's A History of the Indian Villages and Place Names in Pennsylvania identifies it as a Cayuga language word meaning "place of floating oil" and the name of a Cayuga village in New York.[29] Whatever the meaning, Ricketts also named the glen with the tallest waterfall in the park "Ganoga".[30]

Ricketts' stone house served as the base for the Ozone hiking club of Wilkes-Barre's excursions on the mountain; the club gave its name to Ozone waterfall in the park.[31] In 1879 Ricketts started the North Mountain Fishing Club, for anglers on the lake and creek. Guests of the hotel paid one dollar to fish as a club member. In 1889 Ricketts hired Matt Hirlinger and five other men to build the trails along the branches of Kitchen Creek and its waterfalls. It took them four years to complete the trails and stone steps through the glens.[17][32]

One of the highest spots on North Mountain (and in the park today) was an outlook point where Ricketts built a 40-foot (12 m) wooden observation tower for his guests. After the first tower collapsed, he built a 100-foot (30 m) replacement, and named the site Grand View. From the tower, people could see for 20 miles (32 km).[17][32][33]

Lumber era

For over 20 years, Ricketts was "land poor"; he owed much on the mortgages on his vast land holdings, and there were no good means to transport the estimated 1,400,000,000 board feet (3,300,000 m3) of lumber from most of his land to sawmills. Large-scale lumber operations of that time floated logs on major streams or used logging railroads, but neither was available to Ricketts. His small sawmill near the stone house closed by 1875, and he was only able to sell two major tracts of land in his lifetime. In 1872 he sold 14,000 acres (5,700 ha) north of the park to a group of investors that included himself; this deal seems to have been for shares of stock (not cash), and the deed for the sale was not recorded until 1893. Ricketts sold 13,000 acres (5,300 ha) along Bowman Creek, including the easternmost parts of the park, to Albert Lewis in 1876; Lewis hoped to build a branch line of the Lehigh Valley Railroad along the creek. In the 1870s and 1880s, Ricketts tried repeatedly and unsuccessfully to find partners and investors who would help him cut the lumber on his land and build a rail line to it.[34]

Finally in 1890, Harry Clay Trexler, J.H. Turrell, Ricketts, and partners formed the Trexler and Turrell Lumber Company and leased 5,000 acres (2,000 ha) of Ricketts' land near Ganoga Lake. The company built a sawmill and lumber town named Ricketts on Mehoopany Creek. The town, which was in both Sullivan and Wyoming counties, had 800 inhabitants at its peak and extended into the northernmost section of the park. Rail lines were built to the mills at Ricketts, including the Bowman Creek branch of the Lehigh Valley Railroad which opened in 1883, and also provided passenger service to the hotel on Lake Ganoga.[35][36] According to Petrillo's Ghost Towns of North Mountain: Ricketts, Mountain Springs, Stull: "Ricketts was on the verge of financial disaster for two decades until the Lehigh Valley Railroad was constructed through his lands."[37]

Trexler and Turrell paid Ricketts $50,000 in both 1890 and 1891, and continued to cut his land and pay him for the timber until 1913. By 1911, the main sawmill at Ricketts could cut 125,000 board feet (290 m3) a day and was supported by three locomotives with 62 cars on 22 miles (35 km) of track. Within the park, the area around what became Lake Jean was cut in the 1890s, and Cherry Ridge (east of Red Rock Job Corps Center) and land around Lake Leigh were the last areas cut by the Ricketts mill. Timber in the east part of the park and along Bowman Creek was cut by Lewis' company, which also used logging railroads and even ran track down the Allegheny Front at Phillips Creek.[38][39] Lewis' firm built a splash dam on Bowman Creek to help float logs downstream in 1891, then used the lake to cut ice for refrigeration. A second dam and lake were added in 1909 and the icehouses were on state park land; the ice industry supported the small village and post office of Mountain Springs.[40] Ricketts ran his own ice cutting business on Ganoga Lake from 1895 to about 1915.[41]

Within a decade of the railroad reaching his lands, Ricketts was out of the hotel business. The North Mountain House hotel was threatened by a forest fire in 1900; the subsequent loss of much of the surrounding old-growth forest led to decreased numbers of hotel guests. Changing tastes may have also played a role in the decline in popularity; the hotel had over 150 guests in August 1878, but only about 70 guests in August 1894.[42] The wooden addition was torn down in 1897 or 1903,[b] and "despite profits, Ricketts became disenchanted with the hotel business and closed his hotel in 1903", though the stone house remained the Ricketts family's summer home.[43] Passenger rail service to Ganoga Lake ended when the hotel closed; the fishing club closed that year as well, but was re-formed in 1907.[17] In 1903 another large fire on North Mountain threatened the sawmill in the lumber town of Ricketts.[44]

Not all of Ricketts' plans were financially successful; between 1905 and 1907 he built three dams to generate hydroelectric power within what became the park, forming Lake Leigh at the site of Sickler's mill, Lake Rose at the site of Dodson's mill, and Lake Jean (which incorporated the natural Mud Pond) north of these. Lakes Leigh and Jean were named for Ricketts' daughters, while Rose was a Ricketts family name.[22][b] The Lake Leigh dam was made of concrete and cost $165,000 (approximately $4,197,000 in 2016), while the other two dams were log cribs filled with earth and cost a total of $300,000 (approximately $7,632,000 in 2016).[25] If the project had been successful, the plan was to rebuild the two log and timber dams in concrete,[45] however, the "dams were poorly constructed and could not be used for hydroelectric purposes".[20][22] After the Panic of 1907, Ricketts wife told him to stop the hydroelectric project before he lost all of their money;[45] this prompted him to say "I used to be land poor, but now I'm dam poor".[46]

Modern era

In 1913, Ricketts opened the glens and their waterfalls to the public, charging $1 for parking. Although this fee was unpopular, it remained in place until the land became a state park.[47] After Ricketts died in 1918,[48] the Pennsylvania Game Commission bought 48,000 acres (19,000 ha) from his heirs, via the Central Pennsylvania Lumber Company, between 1920 and 1924. This became most of Pennsylvania State Game Lands Number 13, west of the park in Sullivan County.[49] These sales left the Ricketts heirs with over 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) surrounding Ganoga Lake, Lake Jean and the glens area of the park. An area encompassing 22,000 acres (8,900 ha) was approved as a national park site in 1935,[3][50][51] and the National Park Service operated a Civilian Conservation Corps camp at "Ricketts Glynn" (sic).[52][53] The funding to create a National Park at Ricketts Glen was "sidetracked" in 1936 when the money was redirected to the Resettlement Administration for "direct relief".[54] Similar projects at French Creek, Raccoon Creek, Laurel Hill, Blue Knob, and Hickory Run were also defunded (all are now Pennsylvania state parks). The financial difficulties of the Great Depression and World War II brought an end to this plan for development.[3][54][d]

Arthur James, the Governor of Pennsylvania, signed legislation creating Ricketts Glen State Park on August 1, 1941. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania bought 1,261 acres (510 ha), including the glens and their waterfalls, from the heirs for $82,000 on December 31, 1942. The new state park opened to the public on August 1, 1943;[55] however, the park's official history says "recreational facilities first opened in 1944".[3] The state bought a total of 16,000 acres (6,500 ha) more from the heirs in 1945 and 1950 for $68,000; the park today has about 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) from the Ricketts family and about 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) acquired from others.[3][14][49]

The state's original plans for the new park included building an inn, an 18-hole golf course and country club, and a winter sports complex for skiing, ice boating, and tobogganing, as well as a beach with bathing facilities, cabins, and a tent camping area. Only the last three were actually built, all south of Lake Jean; the Hayfield area north of Lake Jean was to have had the facilities for golf and tennis, and the inn and winter sports complex were to have been atop Cherry Ridge, at an elevation of 2,461 feet (750 m).[14][57]

A 1947 newspaper article estimated that the new park would have 50,000 visitors that year, and detailed the work the state had done since acquiring the land. The Falls Trail through the glens was rebuilt, all the stone steps were replaced, and signs were added. Out of concern for greater safety, footbridges with handrails replaced those made from hewn logs, overhanging rock ledges were removed in places, and the trail was rerouted near some falls. In the southern end of the new park, the state built the Evergreen Trail past Adams Falls,[58] as well as a new parking area for 200 cars and a concession stand, both along Pennsylvania Route 118 (PA 118).[14]

The state made other improvements in the park, including replacing or removing all of Ricketts' dams. At Lake Jean it built an earthen dam in 1949–1950 to replace Ricketts' 1905 timber dam; the new dam increased the size of Lake Jean to 245 acres (99 ha) and its eastern end now included the former Mud Pond. On April 20, 1958, the 1907 concrete dam at Lake Leigh developed a hole, causing Pennsylvania State Police to evacuate close to 2,000 people from the park. Engineers from the state inspected the dam and made a second breach in the dam near ground level, draining the lake. The resulting flow of water destroyed some of the hiking paths in Glen Leigh and the fish stocked in the lake wound up in Kitchen Creek. The Lake Jean dam was repaired in 1956. The last of Ricketts' dams, at Lake Rose, was breached in 1959 after remnants of a hurricane filled the lake to capacity. The rest of the 1905 dam was removed in 1969.[22][23][59] At Grand View the state built a wooden fire tower at the site of Ricketts' earlier observation tower, then replaced it with a 100-foot (30 m) steel tower. The tower is usually closed to the public, but may be visited if it is staffed by a forest fire warden. From the tower, three states and eleven Pennsylvania counties can be seen.[32]

Ricketts Glen State Park was the site of a Cold War era radar station.[60] The Benton Air Force Station in the north of the park at what is now the Red Rock Job Corps Center was constructed during 1950 and 1951. Part of the 648th Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron based at Fort Indiantown Gap, the radar station was a "frontline defender of national security".[60] About 300 airmen served at the radar station during the height of the Cold War. Barracks were constructed and recreational facilities for the airmen were provided. In 1963 the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) began jointly operating the radar station; the 648th Squadron was inactivated in 1975 and the Job Corps center was established in 1978, using the barracks and recreational facilities as the Red Rock Job Corps Center. As of 2010, the radar dome is still fully functional and is used by the FAA as an auxiliary radar to the tower at Wilkes-Barre/Scranton International Airport.[60]

On October 12, 1969, the Glens Natural Area and its waterfalls was named a National Natural Landmark, and it became a Pennsylvania State Park Natural Area in 1993, which guarantees it "will be protected and maintained in a natural state".[3][14] In 1987 the park's ten cabins opened.[61] In 1997 the park was named one of the first 73 Important Bird Areas in the state by the Pennsylvania chapter of the National Audubon Society.[62] That same year heavy rains washed out two bridges on the Falls Trail; because of the difficulty of transporting materials on the trail, an Army National Guard helicopter dropped 36-foot (11 m) poles into the glens to rebuild the bridges in early 1997.[63] In the winter of 1997 ice climbing was allowed in the Ganoga Glen section of the park for the first time.[64] That same year training was undertaken by local fire companies to rescue people injured in the park when icy conditions make reaching and transporting them especially treacherous.[65] In 1998 a project to "repair and improve the Falls Trail" began, with three park employees carrying materials in on foot to stabilize the trail, fix steps, cut down on erosion, and repair some bridges. Originally planned to take four years; it ended up taking six years to complete and cost nearly $1 million.[32][66]

In September 1999 the remnants of Hurricane Floyd caused massive damage to the park, temporarily closing it and downing thousands of trees. The DCNR hired Carson Helicopters to salvage timber from the downed beech, cherry, maple, and oak trees for $994,000; a crew of 36 workers spent several months cutting the fallen trees into manageable logs, then helicopters flew the logs to the Hayfield area of the park. The salvage operation ran until the fall of 2001, and yielded 3,500,000 board feet (8,300 m3) of lumber. The operation had revenue of almost $7 million, and had the ecological advantage of not requiring heavy logging equipment or new roads in the park.[67][68][69][70]

Some of the money from the helicopter logging operation was used for park improvements, including a new $1.7 million visitor center and park office, which opened in December 2001.[69][70][71] In 2002 the park had "up to a half-million visitors each year".[4] Beginning in 2003 the campsites in the park, by then over 50 years old, were refurbished.[32] In 2004 the park and surrounding Pennsylvania State Game Lands were named an Important Mammal Area,[72][73] and in July the park was featured as a day trip in the Travel section of The New York Times.[74] On June 28, 2006 a 100-year flood caused widespread damage in the park, washing out many of the recently completed improvements to the hiking trails along Kitchen Creek.[32] In 2007 the park was one of the first ten parks to be featured in the Pennsylvania Cable Network's series on the state's park system.[75] Lake Jean was drained starting April 27, 2015 to allow replacement of the 65-year old dam control tower. The repairs were finished October 20, 2015, and the lake was full again by January 3, 2016.[76] The DCNR has named Ricketts Glen one of "25 Must-See Pennsylvania State Parks", citing its old-growth forest and many waterfalls and its status as a National Natural Landmark.[6]

Geology and climate

Ricketts Glen State Park covers two different physiographic provinces: the Allegheny Plateau in the north, and the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians in the south. The boundary between these is a steep escarpment known as the Allegheny Front, which rises up to 1,200 feet (370 m) above the land to the south. Within the park, Kitchen Creek has its headwaters on the dissected plateau, then drops approximately 1,000 feet (300 m) down the Allegheny Front in 2.25 miles (3.62 km). Much of this drop occurs in Glen Leigh and Ganoga Glen, two narrow valleys carved by branches of Kitchen Creek, which come together at Waters Meet. Ricketts Glen lies south of and downstream from Waters Meet, and here the terrain becomes less steep. There are 24 named waterfalls in the three glens.[30][56][77]

The rocks exposed in the park were formed in the Devonian and Carboniferous periods between 370 and 340 million years ago, when the land was part of the coastline of a shallow sea that covered a great portion of what is now North America. The high mountains to the east of the sea gradually eroded, causing a build-up of sediment made up primarily of clay, sand and gravel. Tremendous pressure caused the formation of the sedimentary rocks that are found in the park and in the Kitchen Creek drainage basin: sandstone, shale, siltstone, and conglomerates.[56]

There are four distinct rock formations within Ricketts Glen State Park. The most recent and highest of these is the late Mississippian Mauch Chunk Formation, composed of "grayish-red shale, siltstone, sandstone, and some conglomerate".[78] This forms the highest points on the Allegheny Plateau and is found north of Lake Jean, forming the land beneath the Red Rocks Job Corps Center and Cherry Ridge to the east. The next formation below this is the Mississippian Pocono Formation, which is buff or gray sandstone with conglomerate and siltstone inclusions. This forms most of the Allegheny Plateau and underlies the park office, Lake Jean and the former Lakes Rose and Leigh. The boulders of the Midway Crevasse, which the Highland Trail passes through, are Pocono Formation sandstone.[56][78]

The third of the rock formations within the park is the Huntley Mountain Formation, from the late Devonian and early Mississippian. This is made of layers of olive green to gray sandstone and gray to red shale. The Huntley Mountain Formation is relatively hard and erosion resistant. It caps the Allegheny Front and has kept it from eroding as much as the softer Catskill Formation, to the south. The Catskill Formation is the lowest and oldest layer in the park, and is composed of red shale and siltstone up to 370 million years old. The Allegheny Front within the park is named North Mountain and Red Rock Mountain, with the latter name coming from an exposed band of Huntley Formation red shale and sandstone visible along Pennsylvania Route 487 (PA 487).[56][79][80][81]

Geologists and the official Ricketts Glen State Park web page classify the falls at Ricketts Glen State Park into two types. Wedding-cake falls descend in a series of small steps. Within the park, this type of falls usually flows over thin layers of Huntley Mountain Formation sandstone. In bridal-veil falls, the second type, water falls over a ledge and drops vertically into a plunge pool in the stream bed below. Within the park, this type of falls flows over Catskill Formation rocks or the red shale and sandstone of the Huntley Formation. In the park, the harder caprock which forms the ledge from which the bridal-veil falls drops is gray sandstone. The softer red shale below is eroded away by water, sand and gravel to form the plunge pool.[3][56] Brown's book Pennsylvania waterfalls: a guide for hikers and photographers uses four types to classify waterfalls: falls, cascade, slide, and chute.[82]

About 300 to 250 million years ago, the Allegheny Plateau, Allegheny Front, and Appalachian Mountains all formed in the Alleghenian orogeny. This happened long after the sedimentary rocks in the park were deposited, when the part of Gondwana that became Africa collided with what became North America, forming Pangaea. In the years since, up to 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of rock has been eroded away by streams and weather. At least three major glaciations in the past million years have been the final factor in shaping the land that makes up the park today.[56][79][83]

The effects of glaciation have made Kitchen Creek within the park "unique compared to all other nearby streams that flow down the Allegheny Front", as it is the only one with an "almost continuous series of waterfalls".[56] Before the last ice age, Kitchen Creek had a much smaller drainage basin; during the ice age, glaciers covered all of the park except the Grand View outcrop. About 20,000 years ago the glaciers retreated to the northeast and glacial lakes formed. Drainage from the melting glacier and lakes cut a sluiceway, or channel, that diverted the headwaters of South Branch Bowman Creek into the Glen Leigh branch of Kitchen Creek. Glacial deposits of debris 20 to 30 feet (6.1 to 9.1 m) thick formed a dam blocking water from Ganoga Lake and what became Lake Jean from draining into Big Run, a tributary of Fishing Creek. The water was instead diverted into the Ganoga Glen branch of Kitchen Creek.[56]

These diversions added about 7 square miles (18 km2) to the Kitchen Creek drainage basin, increasing it by just over 50 percent.[56][84] The result was increased water flow in Kitchen Creek, which has been cutting the falls in the glens since. The gradient or slope of Kitchen Creek was fairly stable for its flow when it had a much smaller drainage basin, as Phillips Creek to the east still does. Kitchen Creek is now too steep for its present amount of water flow, and over time erosion will decrease the creek's slope and make it less steep.[56] There are rocks with glacial striations visible within the park.[32]

According to the United States Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System, Ricketts Glen State Park is at an elevation of 2,198 feet (670 m).[1] The two highest points in the park are Cherry Ridge, made of Mauch Chunk Formation rock, at 2,461 feet (750 m),[57] and the Grand View outcrop of Huntley Mountain Formation sandstone, at 2,444 feet (745 m).[56][85] The highest elevation waterfall in the park is Mohawk Falls in Ganoga Glen at 2,165 feet (660 m);[86] the lowest elevation waterfall is Adams Falls, in Ricketts Glen just south of PA 118, at 1,214 feet (370 m).[87]

Weather

Ricketts Glen State Park is on the Allegheny Plateau, which has a continental climate with occasional severe low temperatures in winter and average daily temperature ranges (the difference between the daily high and low) of 20 °F (11 °C) in winter and 26 °F (14 °C) in summer.[88] The park is in the Huntington Creek watershed, where the mean annual precipitation is 40 to 48 inches (1016 to 1219 mm).[89] Weather records for Ricketts Glen State Park show that the highest recorded temperature at the park was 103 °F (39 °C) in 1988, and the record low was −17 °F (−27 °C) in 1984. On average, January is the coldest month, July is the hottest month, and June is the wettest month.[90]

| Climate data for Ricketts Glen State Park | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 33 (1) |

36 (2) |

46 (8) |

59 (15) |

70 (21) |

78 (26) |

82 (28) |

80 (27) |

73 (23) |

62 (17) |

49 (9) |

37 (3) |

58.8 (15) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 15 (−9) |

17 (−8) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

44 (7) |

53 (12) |

58 (14) |

56 (13) |

49 (9) |

38 (3) |

30 (−1) |

21 (−6) |

36.8 (2.7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.76 (70.1) |

2.52 (64) |

3.13 (79.5) |

3.45 (87.6) |

3.80 (96.5) |

4.99 (126.7) |

4.07 (103.4) |

3.30 (83.8) |

4.49 (114) |

3.21 (81.5) |

3.38 (85.9) |

3.01 (76.5) |

42.11 (1,069.5) |

| Source: The Weather Channel[90] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

It has been estimated that before the arrival of William Penn and his Quaker colonists in 1682, up to 90 percent of what is now Pennsylvania was covered with woods: over 31,000 square miles (80,000 km2) of eastern white pine, eastern hemlock, and a mix of hardwoods.[91] By 1890, Ricketts' land was the largest tract of old-growth forest remaining in the state, and though he made his fortune clearcutting nearly all his land, the forests in the glens of Ricketts Glen State Park were "saved from the lumberman's axe through the foresight of the Ricketts family".[58] The rough terrain of the glens made it difficult to harvest timber from the area. Many of the old-growth trees are believed to be over 500 years old, and ring counts on fallen trees have revealed ages of over 900 years.[23]

The forests in and around Ricketts Glen State Park are some of the most extensive in northeastern Pennsylvania, and provide habitat for a wide variety of woodland creatures. The swampy areas in the park provide a habitat for plants like black gum, yellow birch, cinnamon fern, sphagnum and various sedges.[92] The old-growth forest in the Glens Natural Area is mostly eastern hemlock, eastern white pine, and oaks, and the park is home to 85 species of shrubs, woody vines, and trees, including seven kinds of conifers.[93]

The streams and lakes of Ricketts are fisheries for many fish species,[3][23] although fishing is prohibited in the glens area.[3] In 2009, 4.15 miles (6.68 km) of Kitchen Creek downstream from Waters Meet and all of Phillips Creek were classified as Class A Wild Trout Waters,[94] defined by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission as "streams which support a population of naturally produced trout of sufficient size and abundance to support a long-term and rewarding sport fishery".[95]

Lake Jean is home to brook trout, brown trout, brown bullhead, and yellow bullhead.[96] Acid rain with a pH near 3.0 has altered the ecology of the lakes and region; in Lake Jean low pH has decreased the number and quality of insects and plankton at the base of the food chain. Fish which are acid tolerant are predominant, including fathead minnows, muskellunge, pumpkinseed, walleye, and yellow perch. Predators like chain pickerel and largemouth bass are relatively few in number, and adult fish appear to grow rapidly but breed comparatively poorly.[23] Since 1996, the DCNR has added 11 short tons (10.0 t) of powdered lime to the lake each year to make the pH more neutral.[32]

Glens Natural Area

A registered National Natural Landmark since 1969, the Glens Natural Area is the main scenic attraction in the park and covers 2,845 acres (1,151 ha).[97] Among perhaps 2,000 acres (810 ha) of old-growth forest,[98] two branches of Kitchen Creek cut through the deep gorges of Ganoga Glen and Glen Leigh and unite at Waters Meet; then flow through Ricketts Glen. These old trees are commonly up to 100 feet (30 m) tall, with diameters of almost 4 feet (1.2 m). The park has a great variety of trees as it lies at the boundary between the northern and southern types of hardwoods. In 1993, the state designated the Glens Natural Area a State Park Natural Area, which means that it "will be protected and maintained in a natural state".[3] No buildings or latrines are allowed in the natural area, and the bridges in it are built with wood, not steel or concrete.[32]

A series of trails parallels the branches of Kitchen Creek as they course down the Glens. Glen Leigh features eight named waterfalls and is south of the former Lake Leigh. Ganoga Glen is southeast of the former Lake Rose and has ten named falls, including the 94-foot (29 m) Ganoga Falls, the tallest in the park. The DCNR recognizes three named waterfalls in Ricketts Glen just south of Waters Meet, plus Adams Falls 2 miles (3.2 km) farther downstream at PA 118. Adams Falls, the southernmost and one of the most scenic in the park, is about 0.1 miles (160 m) south of PA 118, via an easy stroll along a trail from the parking lot.[3][32][77]

Brown's Pennsylvania waterfalls: a guide for hikers and photographers recognizes these 22 named falls plus two more in the park. One is on Shingle Cabin Brook as it enters Kitchen Creek just south of Waters Meet; the other, Kitchen Creek Falls, is directly below the PA 118 highway bridge, which obscures much of the view. There are also several unnamed falls in the park, such as a good-sized unnamed waterfall on a tributary of the Ganoga Glen branch of Kitchen Creek, or the "forgotten falls" on the South Branch Bowman Creek.[3][32][77]

The Falls Trail includes the trails through the glens, plus the 1.2-mile (1.9 km) Highland Trail, which connects the top ends of Ganoga Glen and Glen Leigh to form a 3.2-mile (5.1 km) triangular loop, and passes through the "Midway Crevasse," a crack in Pocono Formation rock. All but two of the named waterfalls are either on the triangular loop or 0.5 miles (0.80 km) south of it. Hiking the entire Glens area on the Falls Trail loop, beginning and ending at PA 118, covers 7.2 miles (11.6 km). A shorter hike involves parking at Lake Rose, near the junction of Ganoga Glen and the Highland Trail.[3]

Mammals

Ricketts Glen State Park was named part of an Important Mammal Area because it "support[s] critical habitat for a wide range of mammals"; Pennsylvania has 64 wild mammal species.[72] The park has an extensive forest cover of hemlock-filled valleys and hardwood-covered mountains, which makes it a habitat for big woods wildlife. Animals such as white-tailed deer, black bear, red and gray squirrels, porcupine, and raccoon are seen fairly regularly. Less common creatures include beaver, bobcat, coyote, fisher, mink, muskrat, red fox, and river otter. In addition to mammals, Ricketts Glen is also known for its wild turkeys, wild flowers, butterflies, dragonflies, and the occasional timber rattlesnake.[32][92][99][100]

White-tailed deer became locally extinct on Ricketts' land by 1912, mirroring the sharp decline in Pennsylvania's deer population from overhunting and loss of habitat in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[41][101] The state imported nearly 1,200 white-tailed deer from Michigan between 1906 and 1925 to re-establish the species throughout Pennsylvania, and Ricketts brought deer to the area of the park in 1914. Pennsylvania's deer population rebounded from roughly one thousand in 1905 to roughly one million in 1928.[100][101][102] Deer are now one of the most numerous mammals in the park, and their overbrowsing threatens development of trees and plants there. The deer eat most of the saplings and shrubs before they can reach their full size, which reduces the number of low lying plants many birds use for shelter.[23] The white-tailed deer became the official state animal in 1959.[102] By 2001, deer populations had increased to the point where it was feared that "Pennsylvania is losing its vegetative diversity from deer over-browsing".[23]

Other locally extinct mammals in Pennsylvania include bison, grey wolf, lynx, marten, moose, mountain lion, and wolverine. Beaver and river otter have been successfully reintroduced.[103] In 1995 and 1996, 39 fishers were released in the State Game Lands adjoining the park, and breeding populations appear to have been reestablished.[104] The coyote seems to have come to the state in the 1930s.[105] Black bear and wild turkey populations were also severely affected by overhunting and loss of habitat; the recovery of their populations in the 20th century has been "aided by the re-growth of the eastern deciduous forest".[106] Bears prefer a mixed forest of hickory and oak with an understory of shrubs such as blueberry and laurel; they use patches of coniferous forest for cover during the winter months.[106]

Important Bird Area

The Pennsylvania Audubon Society has designated all 13,050 acres (5,280 ha) of Ricketts Glen State Park a Pennsylvania Important Bird Area (IBA);[99] an IBA is defined as a globally important habitat for the conservation of bird populations. The state park was originally part of the much larger North Mountain IBA, which encompassed 114,978 acres (46,530 ha), including all of the park and nearby Pennsylvania State Game Lands Numbers 13, 57, and 66.[2][23] Ricketts Glen State Park is featured in the Audubon Society's Susquehanna River Birding and Wildlife Trail Guide.[99][107]

Ornithologists and bird watchers have recorded a total of 75 species at Ricketts Glen State Park and within the North Mountain IBA. Several factors contribute to the high total of bird species observed: there is a large area of forest in the park, as well as great habitat diversity. The location along the Allegheny Front also contributes to the diverse bird populations.[23] The North Mountain IBA was said to be the "largest extant forest" in northeastern Pennsylvania and one of the largest forests in the state of Pennsylvania.[23] It was officially adopted by the North Branch Bird Club and was "well-known" by members of local Audubon societies and the Pennsylvania Society for Ornithology.[23]

Ricketts Glen State Park provides a breeding habitat for four species of flycatchers and two species of waterthrushes. American bittern nest near the park. Bald eagle are frequent visitors to the park, and some ornithologists believe they may be nesting there since adult pairs have been observed with their young.[23] The park is a nesting location for three "rare" birds, including two birds of prey (the northern goshawk and northern harrier), and Swainson's thrush, as well as one "at risk" duck, the green-winged teal.[23]

Ricketts Glen State Park has extensive acreage of "interior forest" that is far from open space; several bird species that are area-sensitive are found within these forests in the park, including the black-throated green warbler, red-eyed vireo, dark-eyed junco and black-capped chickadee. Two species of owl, barred and northern saw-whet, inhabit the deep forests.[23] The hemlock forests of the glens are home to the Louisiana waterthrush, Acadian flycatcher, Blackburnian warbler, blue-headed vireo, magnolia warbler, brown creeper, golden-crowned kinglet and winter wren.[23] Wood thrush are found in the lower elevations of the park and are replaced within the ecosystem by hermit thrush at the higher elevations.[23] The Canada warbler and black-throated blue warbler are on several watchlists, but are common within the park. The Canada warbler inhabits blueberry thickets with white-throated sparrow, while the black-throated blue warbler is found in the forests atop the plateau with the least flycatcher.[23] Common raven are regularly seen soaring over the forests of the park looking for carrion. Canada goose are present in the park and have been classified as a "pest" due to their high numbers and the large amount of fecal waste they leave on the shores of Lake Jean.[23] Ricketts Glen's forests also support populations of Nashville and yellow-rumped warblers, yellow-bellied sapsucker, red-breasted nuthatch, and purple finch.[23]

Recreation

Hunting, fishing and boating

10,144 acres (4,105 ha) of the park are open to hunting and trapping. Common game animals include black bear, gray squirrel, ring-necked pheasant, ruffed grouse, wild turkey, and white-tailed deer. The common fur-bearing animals in Ricketts Glen State Park are beaver, bobcat, coyote, mink, muskrat, and raccoon.[3]

Lake Jean is a 245-acre (99 ha) warm-water fishery that is open to fishing, ice fishing, swimming, and boating.[3][74] Common game fish include panfish, trout and bass. Boating is permitted on the lake, which has two boat launches. Gasoline-powered boats are prohibited. Canoes and other human-powered boats are permitted, as are sail boats and electric-powered vessels. There is a boat rental concession on the lake, which has canoes, kayaks, row boats, and paddle boats available. No fishing is allowed in the Glens Natural Area.[3][32]

Cabins, camping, swimming, and picnics

Ricketts Glen State Park has 10 modern cabins that are available to rent on a year-round basis. All cabins are furnished with electric heat, two or three bedrooms, living room, kitchen, and bath. Cabin renters must bring their own household items such as linens and cookware. One cabin is ADA accessible.[3][108] There are 120 campsites at Ricketts Glen State Park. Each campsite has access to washhouses with flush toilets, showers, and laundry tubs. The campsites also have fire rings and picnic tables. There are two camping areas on the shores of Lake Jean, with one of the campgrounds on a peninsula.[109] There is also an organized group tenting area, which can accommodate six groups of up to 40 persons.[3][32]

The 600-foot (180 m) beach on Lake Jean is open from mid-May through mid-September. A concession stand and modern restrooms are at the beach. Lifeguards have not been provided since 2008; visitors swim at their own risk. Picnic areas are at Lake Jean and the PA 118 access area at the Falls Loop Trail trailhead. Charcoal grills are provided for use at the picnic areas.[3][110][111]

Environmental education and trails

Environmental education specialists lead guided tours of parts of the park from March through November. The walks give school groups, scouting organizations, and other visitors a close and informed look at natural wetlands, old-growth forests, waterfalls, flora and fauna, and geologic formations.[3] Other programs are held in the park office, on topics such as safety around wild animals.[112] In summer and fall, park educators lead "Ghost Town Walks" to the ruins of the lumber village of Ricketts and to adjoining State Game Lands.[36]

There are 26 miles (42 km) of hiking trails at Ricketts Glen State Park, and a 12.5-mile (20.1 km) trail loop is open for horseback riding.[110][113] The trails range from "easy" hikes like the Beach Trail along Lake Jean, to "difficult" hikes such as the Falls Trail loop, which passes by many of the waterfalls of the park.[113] In 2001, John Young in Hike Pennsylvania: An Atlas of Pennsylvania's Greatest Hiking Adventures wrote of the Falls Trail: "This is not only the most magnificent hike in the state, but it ranks up there with the top hikes in the East."[114] In 2003, Backpacker Magazine named the park's Falls Trail loop one of its 30 favorite day hikes in the contiguous United States.[115]

Many of the trails in the park are difficult and hikers are urged to use caution, especially on the Falls Trail, which is steep and often wet and slippery. Each year hikers fall in the glens and have to be rescued, which usually takes dozens of volunteers and up to 11 hours because of the remote locations and rugged terrain.[116][117] As of 2008, the former concession stand along PA 118 in the southern end of the park was used for storage of rescue equipment.[118]

- Falls Trail is a 7.2-mile (11.6 km) difficult loop, estimated to take 4 to 5 hours to hike.[119] The January 2009 issue of Backpacker Magazine named the Falls Trail loop the best hike in Pennsylvania, as part of the magazine's Reader's Choice Awards. It boasts a series of wild, free-flowing waterfalls, each cascading though rock-strewn clefts, and passes through a stand of old-growth forest.[119][120] The park's website stresses the difficulty of the trail, and The New York Times calls it "difficult and potentially dangerous" near the top of glens.[3][74] The Falls Trail was "rehabilitated" in 2008 to make the "easier to hike".[116] The trail is closed during the winter months to hiking, but it is open to ice climbing. The ice climbers must use an ice axe, crampons, and rope.[116]

- Highland Trail is a 1.2-mile (1.9 km) moderate hiking trail at the top of the Falls Trail loop. It passes through the Midway Crevasse, a narrow gap between two large blocks of Pocono sandstone conglomerate.[113]

- Ganoga View Trail is a 2.8-mile (4.5 km) moderate trail named for Ganoga Falls, the highest waterfall in the park. Ganoga View Trail is an alternative route to Ganoga Falls and less difficult than the Falls Trail.[113]

- Grand View Trail is a moderate 1.9-mile (3.1 km) trail which reaches an elevation of 2,449 feet (746 m), the highest point on Red Rock Mountain (which is part of the Allegheny Front). The area is known for its flora, including blooms of mountain laurel in June and rhododendron in July. A firetower is open during the fire season for further viewing.[113]

- Old Beaver Dam Road Trail is a 1.2-mile (1.9 km) easy loop trail that is accessed from a parking lot on PA 487 or the Lake Rose parking area.[3]

- Beach Trail is an easy 0.8-mile (1.3 km) trail that provides access to the Lake Jean day-use and swimming areas from both camping areas.[113]

- Old Bulldozer Road Trail is a 2.9-mile (4.7 km) difficult trail that ascends a bulldozer road that was built during the construction of Ricketts Glen State Park. The trail begins at the parking lot on PA 118 with a short but steep climb and connects with Mountain Springs Trail.[113]

- The Bear Walk Trail is an easy 1-mile (1.6 km) trail from the cabin area to Lake Rose that serves as an access to the longer hiking, cross-country, and snowmobiling trails of the park.[113]

- Evergreen Trail is a self-guided, 1-mile (1.6 km) ecological trail that passes through a stand of old-growth forest that includes an Eastern Hemlock that pre-dates the 1492 arrival of Christopher Columbus.[113]

- Mountain Springs Trail is a 4-mile (6.4 km) moderate trail that is "off the beaten path".[113] It passes the remains of the Lake Leigh dam, the "forgotten falls" and descends the South Branch of Bowman Creek to Mountain Springs Lake, which is owned by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission.[113]

- Cherry Run Trail is near the Lake Leigh dam access. It is a 4.6-mile (7.4 km) moderate trail that passes through groves of cherry trees on an old logging road.[113]

Nearby state parks

The following state parks are within 30 miles (48 km) of Ricketts Glen State Park:[121][122][123][124][125]

- Frances Slocum State Park (Luzerne County)

- Nescopeck State Park (Luzerne County)

- Worlds End State Park (Sullivan County)

Map

Notes

- a. ^ According to William Reynolds Ricketts' HABS history of the house,[20] Petrillo's history of the region Ghost Towns of North Mountain,[17] and the house's NRHP nomination form,[43] the Ricketts brothers bought the lake and surrounding land in 1851, began building the stone house that year, and finished it in 1852. The year 1852 is also carved in stone on the front (west side) of the house, which faced the highway (see this photograph). However, according to Tomasak's The Life and Times of Robert Bruce Ricketts, the brothers purchased the lake, tavern, and land on April 13, 1853, for $550, and had the house built from 1854 to 1855.[126]

- b. ^ All sources agree that the North Mountain House hotel closed in 1903, but differ on the date that the wooden addition used for the hotel was torn down. William Reynold's Ricketts' history for the HABS and Petrillo's book both report it was razed in 1897,[17][20] while McDonald's NRHP nomination form and Tomasak's book give the year as 1903.[43][127]

- c. ^ The Ricketts family is descended from Clan Rose of Kilravock Castle near Nairn in the Scottish Highlands.[22] Before he changed the name to Ganoga Lake in 1881, R. Bruce Ricketts called Long Pond "Highland Lake" for a few years.[27]

- d. ^ As recently as March 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature's World Commission on Protected Areas still classified Ricketts Glen State Park as "Category II, National Park".[128]

References

- 1 2 "Ricketts Glen State Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- 1 2 Trostle, Sharon, ed. (2009). The Pennsylvania Manual (PDF). 119. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Department of General Services. p. 9, Section 9. ISBN 0-8182-0334-X. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "Ricketts Glen State Park". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- 1 2 "Land Baron's Best Deal, Col. R. Bruce Ricketts' Business In 1800s Was Land Speculation. Today the Park Named After Him Represents His Legacy.". The Times Leader. May 12, 2002. p. 1B. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Ricketts Glen State Park". ProtectedPlanet.net. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- 1 2 "Find a Park: 25 Must-see Parks". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- 1 2 Kent, Smith, McCann, pp. 4, 7–11, 85–96, 195–201.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wallace (2005), pp. 4–12, 84–89, 99–105, 145–148, 157–164.

- 1 2 Donehoo, pp. 154–155, 215–219.

- ↑ Wallace (1987), pp. 66–72, 130–132.

- ↑ Wallace (2005), p. 159.

- ↑ Wallace (2005), pp. 136–141.

- ↑ Wren, p. 56, Plate No. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tomasak, pp. 373–374.

- ↑ "Luzerne County 3rd class" (PDF). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Sullivan County 8th class" (PDF). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Petrillo, pp. 40–43.

- ↑ "Columbia County 6th class" (PDF). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ↑ Richter, pp. 3–46.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ricketts, William Reynolds (1936). "William R. Ricketts House, North Mountain Colley, Ganoga Lake, Sullivan County, PA". Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Wilson, Jr., Kenneth T. (Spring 1990). "Sketches from the Susquehanna-Tioga Turnpike". Carver Magazine. 8 (1). Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Petrillo, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Gross, Doug (May 2004). "Pennsylvania Important Bird Area #48" (PDF). Pennsylvania Audubon Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ↑ Tomasak, p. 44

- 1 2 "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2008". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ↑ "History of the Rothrock State Forest". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- 1 2 Bachelder, pp. 186–189.

- ↑ Tomasak, p. 85.

- ↑ Donehoo, pp. 63–64.

- 1 2 Ricketts Glen State Park (PDF) (Map). 1⅛ inch = ½ mile. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. July 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2006. Retrieved November 14, 2009. Note:This is a map on one side giving 22 waterfall names and heights (available at the URL cited) and a park guide on the other side.

- ↑ Kline, David R. (January 6, 2010). "News From Back Home". Benton News. Benton, Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Emenheiser, David (Director) (August 7, 2007). PCN Tours Pennsylvania State Parks: Ricketts Glen State Park (DVD). Pennsylvania Cable Network. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ↑ Tomasak, pp. 100, 323, 327.

- ↑ Petrillo, pp. 43–49.

- ↑ Petrillo, pp. 43–49, 68.

- 1 2 Lamey-Welshans, Jessica (October 26, 2008). "Ghost town of Ricketts brought back to life by state park educator". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ↑ Petrillo, p. 3.

- ↑ Petrillo, pp. 66, 68.

- ↑ Taber, pp. 344–351, 365.

- ↑ Petrillo, pp. 25–36.

- 1 2 Petrillo, pp. 1, 53.

- ↑ Tomasak, pp. 88, 323, 326, 328–329.

- 1 2 3 McDonald, Teresa B. (Ganoga Lake Association) (1980). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Clemuel Ricketts Mansion" (PDF). Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Tomasak, pp. 328–329.

- 1 2 Tomasak, pp. 351–352.

- ↑ Trescott, Paul (May 9, 1954). "Pennsylvania Primps for the Tourist". The New York Times. p. XX15.

- ↑ Tomasak, p. 353.

- ↑ "Colonel Robert Bruce Ricketts (obituary)". The New York Times. November 14, 1918. p. 13.

- 1 2 Petrillo, p. 69.

- ↑ "Federal Park Plans Advance". Reading Eagle. July 14, 1935. p. 8. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Plans Pennsylvania Park: Government is Buying 22,000 Acres Near Wilkes-Barre". The New York Times. May 30, 1935. p. 17.

- ↑ "Camp Information for SP-9-PA". Pennsylvania CCC Archive. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ↑ Paige, Appendix C, Table C-1.

- 1 2 "Ricketts Glen Project Sidetracked". Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin. February 28, 1936. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Rickett's Glen (sic) To Open Sunday: State Forbids Hunting on Tract". Reading Eagle. July 31, 1943. p. 14. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Braun, Duane D.; Inners, Jon D. "Pennsylvania Trail of Geology, Ricketts Glen State Park, Luzerne, Sullivan and Columbia Counties, The Rocks, the Glens and the Falls (Park Guide 13)" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- 1 2 "Cherry Ridge". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- 1 2 "50,000 will see Rickett's Glen Charms". Williamsport Sun. September 4, 1947. p. 12.

- ↑ Tomasak, p. 377.

- 1 2 3 Bartizek, Ron (November 13, 2005). "A Cold War outpost: Radar installation was part of North American defense system scanning for sneak attacks". The Times Leader. p. 1B. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ Kraft, Randy (March 1, 1987). "Camping Isn't What It Used To Be: Roughing It Getting Smoother For Campers". The Morning Call. p. F1. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Audubon names 73 important bird areas in state". Resource: Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. 1997-01-07. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ "Army drops poles into Ricketts Glen". The Resource, Vol. 1 No. 3. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. January 7, 1997. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Winter fun awaits visitors". The Resource, Vol. 2, Issue 1. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. January 1998. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Ricketts Glen practices for rescues on ice". The Resource, Vol. 1 No. 7. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. March 7, 1997. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Ricketts Glen State Park begins project to shore up trail". The Resource, Vol. 2, Issue 8. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. December 1998. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Floyd pays unwelcome visit to state parks". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. October 1999. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Timbering enters new millenium (sic): Trees fly at Ricketts Glen State Park". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. November 2000. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- 1 2 "DCNR rounds out successful year of conservation and recreation". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. January 2002. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- 1 2 Tomasak, p. 380.

- ↑ "State forest, park HQs ready for upgrades". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. November 2001. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- 1 2 "First 44 mammal areas identified across Pa.". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. March 2004. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Important Mammal Areas Project Overview". Pennsylvania Game Commission. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Motyka, John (July 2, 2004). "Waterfalls, Waterfalls Everywhere". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ↑ "PCN tours state parks in a new regular series set to air this summer". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. May 23, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ↑ Bendick, John (January 22, 2016). "State Park Ranger says 'Lake Jean is back!'". The Luminary. Muncy, Pennsylvania. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Brown, pp. 50–52.

- 1 2 "Geologic units in Luzerne county, Pennsylvania". United States Geological Survey. February 11, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- 1 2 Van Diver, pp. 31–35, 153–155.

- ↑ Berg, T. M. (1981). "Atlas of Preliminary Geologic Quadrangle Maps of Pennsylvania: Red Rock" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ↑ "Map 67: Tabloid Edition Explanation" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ↑ Brown, p. xiv

- ↑ Shultz, pp. 372–374, 391, 399, 818.

- ↑ Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Watershed Management, Division of Water Use Planning (2001). Pennsylvania Gazetteer of Streams (PDF). Prepared in Cooperation with the United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Grand View". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 1, 1989. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Mohawk Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Adams Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Climate of Pennsylvania" (PDF). Pennsylvania State University, Pennsylvania State Climatologist. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ↑ Shaw, p. 129.

- 1 2 "Monthly Averages for Ricketts Glen State Park". The Weather Channel Interactive, Inc. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ↑ "The Pennsylvania Lumber Museum - History". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- 1 2 Davis, Anthony F.; Lundgren, Julie A.; et al. (1995). "A Natural Areas Inventory of Sullivan County" (PDF). Pennsylvania Science Office of The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ↑ Chamuris, George P. (June 18, 2005). "Hiker's Guide to the Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines of Ricketts Glen State Park" (Third ed.). Bloomsburg University. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Notice: Additions to List of Class A Wild Trout Waters" (PDF). Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. January 30, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Class A Wild Trout Waters" (PDF). Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. February 14, 2009. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ↑ Frey, Aaron (Spring 2007). "Biologist Reports: Lake Jean, Luzerne County, Spring 2007, Sampling Gear: Trap Nets & Electrofishing". Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Natural Areas". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ↑ Davis, Mary Byrd (January 23, 2008). "Old Growth in the East: A Survey. Pennsylvania" (PDF). primalnature.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Audubon Pennsylvania; Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (2004). Susquehanna River Birding and Wildlife Trail (Searchable database). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- 1 2 Ostrander, pp. 13–17.

- 1 2 Rosenberry, Christopher S.; Fleegel, Janine Tardiff; Wallingford, Bret D. (December 2009). Management and Biology of White-Tailed Deer (PDF). Pennsylvania Game Commission. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- 1 2 "Abbreviated History of Pennsylvania's White-Tailed Deer Management". Pennsylvania Game Commission. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ↑ Whiteford, p. 23.

- ↑ Hardisky, Thomas S. (editor). "Pennsylvania Fisher Reintroduction Project". Pennsylvania Game Commission, Bureau of Wildlife Management. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ↑ "Shedding Light on the Eastern Coyote" (PDF). Pennsylvania Game Commission. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- 1 2 Goodrich, Laurie J.; Brittingham, Margaret; Bishop, Joseph A.; Barber, Patricia. "Wildlife Habitat in Pennsylvania: Past, Present, and Future" (PDF). Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ "A Pennsylvania Recreational Guide for Ricketts Glen State Park" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Cabins and Yurts". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Camping at Ricketts Glen State Park" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- 1 2 "Park Spotlight: Ricketts Glen State Park". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. June 18, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Pa. park beaches to open without lifeguards: The move is not based on economics, the state says, but some see a problem". The Times Leader. May 31, 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-01-08. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ↑ Eaton, Alissa (June 9, 2008). "Wilderness educator shares the bear facts about animal attacks". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Ricketts Glen State Park: Hiking". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ↑ Young, p. 66.

- ↑ Lanza, Michael (June 2003). "Getaways: These are the Days: 30 of the Best Day Hikes in the Lower 48". Backpacker Magazine. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Donlin, Patrick (March 30, 2009). "Hikers at Ricketts Glen urged to use caution". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ↑ "Rickets Glen State Park manager earns award". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. June 2000. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ↑ Tomasak, p. 374.

- 1 2 Mitchell, pp. 44–52.

- ↑ "Magazine names trail at Ricketts Glen best hike in Pennsylvania". Press Enterprise. January 28, 2009. p. 5.

- ↑ Michels, Chris (1997). "Latitude/Longitude Distance Calculation". Northern Arizona University. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Find a Park by Region (interactive map)". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ↑ 2015 General Highway Map Columbia County Pennsylvania (PDF) (Map). 1:65,000. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ↑ 2015 General Highway Map Luzerne County Pennsylvania (PDF) (Map). 1:65,000. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ↑ 2015 General Highway Map Sullivan County Pennsylvania (PDF) (Map). 1:65,000. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ↑ Tomasak, p. 38.

- ↑ Tomasak, p. 313.

- ↑ "Ricketts Glen State Park". ProtectedPlanet.net. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

Works cited

- Bachelder, John B. (1875). Popular resorts, and how to reach them. Combining a Brief Description of the Principal Summer Retreats in the United States, and the Routes of travel Leading to Them. Boston, Massachusetts: J.B. Bachelder Publishing. OCLC 317328980. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- Brown, Scott E. (2004). Pennsylvania waterfalls: a guide for hikers and photographers. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3184-7. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- Donehoo, George P. (1999) [1928]. A History of the Indian Villages and Place Names in Pennsylvania (PDF) (Second Reprint ed.). Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Wennawoods Publishing. ISBN 1-889037-11-7. Retrieved July 29, 2016. ISBN refers to a 1999 reprint edition, URL is for the Susquehanna River Basin Commission's web page of Native American Place names, quoting and citing the book

- Kent, Barry C.; Smith III, Ira F.; McCann, Catherine (Editors) (1971). Foundations of Pennsylvania Prehistory. Anthropological Series of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. OCLC 2696039.

- Mitchell, Jeff (2003). Hiking the Endless Mountains: Exploring the Wilderness of Northeast Pennsylvania. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2648-7. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- Ostrander, Stephen J. (1996). Great Natural Areas in Eastern Pennsylvania. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2574-X. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- Paige, John C. (1985). "Appendix C, Table C-1: Directory of CCC Camps Supervised by the NPS (updated to December 31, 1941).". The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933–1942: An Administrative History. National Park Service, Department of the Interior. OCLC 12072830.

- Petrillo, F. Charles (1991). Ghost Towns of North Mountain: Ricketts, Mountain Springs, Stull (PDF). Wyoming Historical & Geological Society. ISBN 0-937537-00-4. OCLC 25080093.

- Richter, Daniel K. (2002). "Chapter 1. The First Pennsylvanians". In Miller, Randall M.; Pencak, William A. Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ISBN 0-271-02213-2.

- Ricketts, William Reynolds (1936). "William R. Ricketts House, North Mountain Colley, Ganoga Lake, Sullivan County, PA" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- Shaw, Lewis C. (June 1984). Pennsylvania Gazetteer of Streams Part II (Water Resources Bulletin No. 16). Prepared in Cooperation with the United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey (1st ed.). Harrisburg, PA: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Environmental Resources. OCLC 17150333.

- Shultz, Charles H. (Editor) (1999). The Geology of Pennsylvania. Harrisburg and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Geological Society and Pittsburgh Geological Society. pp. 372–374, 391, 399, 818. ISBN 0-8182-0227-0.

- Taber III, Thomas T. (1970). "Chapter 3.3 Ricketts – Trexler and Turrell Lumber Company". Ghost Lumber Towns of Central Pennsylvania: Laquin, Masten, Ricketts, Grays Run. Williamsport, Pennsylvania: Lycoming Print Co. OCLC 1044759.

- Tomasak, Peter (2008). In Command of Time Elapsed: The Life and Times of Robert Bruce Ricketts. Kyttle, Pennsylvania: North Mountain Publishing Company.

- Van Diver, Bradford B. (1990). Roadside Geology of Pennsylvania. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87842-227-7.

- Wallace, Paul A.W.; revised by William A. Hunter (2005). Indians in Pennsylvania (Second ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ISBN 978-1-4223-1493-7. OCLC 1744740. Retrieved December 21, 2009. (Note: OCLC refers to the 1961 First Edition).

- Wallace, Paul A. W. (1987). Indian Paths of Pennsylvania (Fourth Printing ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ISBN 0-89271-090-X. Note: ISBN refers to 1998 impression.

- Whiteford, Richard D. (2006). Wild Pennsylvania: A Celebration of Our State's Natural Beauty. St Paul, Minnesota: Voyageur Press / MBI Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7603-2638-1. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- Wren, Christopher; Wyoming Historical and Geological Society (1914). A Study of North Appalachian Indian Pottery. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: E.B. Yordy Co. OCLC 2510750. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- Young, John (2001). Hike Pennsylvania: An Atlas of Pennsylvania's Greatest Hiking Adventures. Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 0-7627-0924-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ricketts Glen State Park. |

- "Ricketts Glen State Park official large map" (PDF). (2.55 MB)

- "Ricketts Glen State Park official waterfalls map" (PDF). (266.6 KB)

- "Ricketts Glen State Park official campground map" (PDF). (196.9 KB)

- "Ricketts Glen State Park official cabins map" (PDF). (46.2 KB)