Johnson Wax Headquarters

|

Administration Building and Research Tower, S.C. Johnson Company | |

|

Exterior, viewed towards the east, of the Johnson Wax Headquarters building | |

| |

| Location | Racine, Wisconsin |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°42′49″N 87°47′27″W / 42.71361°N 87.79083°WCoordinates: 42°42′49″N 87°47′27″W / 42.71361°N 87.79083°W |

| Built | 1936 |

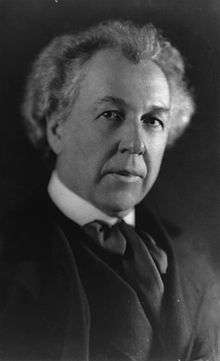

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright; Peters,Wesley W. |

| Architectural style | Late 19th and early 20th centuries American Movements, Other |

| NRHP Reference # | 74002275[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 27, 1974 |

| Designated NHL | January 7, 1976[2] |

Johnson Wax Headquarters is the world headquarters and administration building of S. C. Johnson & Son in Racine, Wisconsin. Designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright for the company's president, Herbert F. "Hib" Johnson, the building was constructed from 1936 to 1939.[3] Also known as the Johnson Wax Administration Building, it and the nearby 14-story Johnson Wax Research Tower (built 1944–1950) were designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1976 as Administration Building and Research Tower, S.C. Johnson and Son.[2]

Design

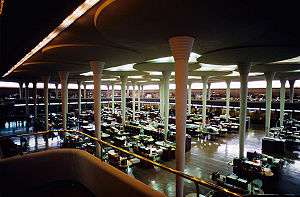

The Johnson Wax Headquarters were set in an industrial zone and Wright decided to create a sealed environment lit from above, as he had done with the Larkin Administration Building. The building features Wright's interpretation of the streamlined Art Moderne style popular in the 1930s. In a break with Wright's earlier Prairie School structures, the building features many curvilinear forms and subsequently required over 200 different curved "Cherokee red" bricks to create the sweeping curves of the interior and exterior. The mortar between the bricks is raked in traditional Wright-style to accentuate the horizontality of the building. The warm, reddish hue of the bricks was used in the polished concrete floor slab as well; the white stone trim and white dendriform columns create a subtle yet striking contrast. All of the furniture, manufactured by Steelcase, was designed for the building by Wright and it mirrored many of the building's unique design features.

The entrance is within the structure, penetrating the building on one side with a covered carport on the other. The carport is supported by short versions of the steel-reinforced dendriform (tree-like) concrete columns that appear in the Great Workroom.[3] The low carport ceiling creates a compression of space that later expands when entering the main building where the dendriform columns rise over two stories tall. This rise in height as one enters the administration building creates a release of spatial compression making the space seem much larger than it is. Compression and release of space were concepts that Wright used in many of his designs, including the playroom in his Oak Park Home and Studio, the Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, and many others.

Throughout the "Great Workroom," a series of the thin, white dendriform columns rise to spread out at the top, forming a celling, the spaces in between the circles are set with skylights made of Pyrex glass tubing. At the corners, where the walls usually meet the ceiling, the glass tubes continue up, over and connect to the skylights creating a clerestory effect and letting in a pleasant soft light. The Great Workroom is the largest expanse of space in the Johnson Wax Building, and it features no internal walls. It was originally intended for the secretaries of the Johnson Wax company, while a mezzanine holds the administrators.

Construction

The construction of the Johnson Wax building created controversies for the architect. In the Great Workroom, the dendriform columns are 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter at the bottom and 18 feet (550 cm) in diameter at the top, on a wide, round platform that Wright termed, the "lily pad." This difference in diameter between the bottom and top of the column did not accord with building codes at the time. Building inspectors required that a test column be built and loaded with twelve tons of material. The test column, once it was built, was tough enough that it was able to be loaded fivefold with sixty tons of materials before the "calyx," the part of the column that meets the lily pad, cracked (crashing the 60 tons of materials to the ground, and bursting a water main 30 feet underground). After this demonstration, Wright was given his building permit.

Additionally, it was very difficult to properly seal the glass tubing of the clerestories and roof, thus causing leaks. This problem was not solved until the company replaced the top layers of tubes with skylights of angled sheets of fiberglass and specially molded sheets of Plexiglas with painted dark lines to resemble the original joints. And finally, Wright's chair design for Johnson Wax originally had only three legs, supposedly to encourage better posture (because one would have to keep both feet on the ground at all times to sit in it). However, the chair design proved too unstable, tipping very easily. Herbert Johnson, needing a new chair design, purportedly asked Wright to sit in one of the three-legged chairs and, after Wright fell from the chair, the architect designed new chairs for Johnson Wax with four legs; these chairs, and the other office furniture designed by Wright, are still in use.

Despite these problems, Johnson was pleased with the building design and later commissioned the Research Tower and a house from Wright known as Wingspread.

Research Tower

The Research Tower was a later addition to the building, and provides a vertical counterpoint to the horizontal administration building. It is one of only 2 existing high rise buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright. Cantilevered from a giant stack, the tower's floor slabs spread out like tree branches, providing for the segmentation of departments vertically. Elevator and stairway channels run up the core of the building. The single reinforced central core, termed by Wright as a tap root, was based on an idea proposed by Wright for the St. Mark's Tower in 1929. Wright recycled the tap root foundation in the Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma in 1952. Freed from peripheral supporting elements, the tower rises gracefully from a garden and three fountain pools that surround its base while a spacious court on three sides provides ample parking for employees.[4]

The Research Tower is no longer in use because of the change in fire safety codes (it has one 29-inch wide twisting staircase), although the company is committed to preserving the tower as a symbol of its history.[3] In 2013, an extensive 12-month restoration was completed. The tower was relit on December 21, 2013 to mark the winter solstice, and SCJ announced that it would be opened for public tours for the first time in its history.[5] The research labs shown on the tour have been set up to appear frozen in time, including beakers, scales, centrifuges, archival photographs and letters about the building.[6]

Legacy

The Johnson Wax buildings are on the National Register of Historic Places, and the Administration Building and the Research Tower were each chosen by the American Institute of Architects as two of seventeen buildings by the architect to be retained as examples of his contribution to American culture. In addition, the Administration Building and Research Tower were both designated National Historic Landmarks in 1976.[2][7]

In 2008, the U.S. National Park Service submitted the Johnson Wax Headquarters and the Research Tower, along with nine other Frank Lloyd Wright properties, to a tentative list for World Heritage Status. The 10 sites have been submitted as one total site. The January 22, 2008 press release from the National Park Service website announcing the nominations states that, "The preparation of a Tentative List is a necessary first step in the process of nominating a site to the World Heritage List."[8]

As of Spring 2013, many parts of the building, including the carport and Research Tower are undergoing extensive restoration work.

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2006-03-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 "Administration and Research Tower, S.C. Johnson Company". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- 1 2 3 Hertzberg, Mark (2010). Frank Lloyd Wright's SC Johnson Research Tower. Rohnert Park: Pomegranate. ISBN 0-7649-5609-4.

- ↑ Robert Sharoff, "A Corporate Paean to Frank Lloyd Wright", The New York Times, April 29, 2014.

- ↑ Michael Burke, "SCJ announces online reservations to begin for Research Tower tours", Racine Journal Times, March 20, 2014.

- ↑ Blair Kamin, "Frank Lloyd Wright's tower worthy of debate, and a trip", Chicago Tribune, April 23, 2014.

- ↑ ____ (, 19), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: _____ (pdf), National Park Service Check date values in:

|date=(help) and Accompanying ____ photos, exterior and interior, from 19___ (32 KB) - ↑ "New US World Heritage Tentative List". Nps.gov. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Lipman, Jonathon. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Johnson Wax Building. New York. Rizzoli. 1986.

- ↑ Lipman, Jonathon. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Johnson Wax Building. New York. Rizzoli. 1986.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johnson Wax Headquarters. |

- Visiting S.C. Johnson

- SC Johnson architecture page includes links to tour information for the Johnson Wax building.

- Johnson Wax Building, is a page from an independent website, Frank Lloyd Wright Roadtrip concentrating on the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Includes photographs.

- Johnson Wax Building at Great Buildings Online