Second Constitutional Era

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Historiography |

The Second Constitutional Era (Ottoman Turkish: ايکنجى مشروطيت دورى; Turkish: İkinci Meşrûtiyyet Devri) of the Ottoman Empire established shortly after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution which forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the constitutional monarchy by the revival of the Ottoman parliament, the General Assembly of the Ottoman Empire and the restoration of the constitution of 1876. The parliament and the constitution of First Constitutional Era (1876–1878) had been suspended by Abdul Hamid in 1878 after only two years of functioning. Whereas the First Constitutional Era had not allowed for political parties, the Young Turks amended the constitution to strengthen the popularly-elected Chamber of Deputies at the expense of the unelected Senate and the Sultan's personal powers, and formed and joined many political parties and groups for the first time in the Empire's history.

A series of elections during this period resulted in the gradual ascendance of the Committee of Union and Progress's (CUP) domination in politics. The second largest party, with which the CUP was involved in a 2-year power struggle, was the Freedom and Accord Party (also known as the Liberal Union or Liberal Entente) founded in 1911 by those that had split off from the CUP. The period survived an attempt by reactionaries to re-institute absolutism. After World War I and the Occupation of Istanbul on 13 November 1918 by the Allies, the parliament's decision to work with the Turkish revolutionaries in Ankara by signing the Amasya Protocol and agreeing in 1920 to the Misak-ı Millî (National Pact) angered the Allies, who forced the sultan to abolish the parliament. The last meeting on 18 March 1920 produced a letter of protest to the Allies, and a black cloth covered the pulpit of the Parliament as reminder of its absent members.

Restoration

The Young Turk Revolution, which began in the Balkan provinces, spread quickly throughout the empire and resulted in the Sultan Abdulhamid II (who had suspended the parliament in 1878, thus ending the first constitutional period of the Ottoman Empire) announcing the restoration of the 1876 constitution and reconvening the parliament on 3 July 1908.

The reason behind the revolt, still localized at that stage, had been the Sultan’s heavily oppressive policies (istibdâd as marked by contemporaries, although many expressed longings for his old-fashioned despotism a few years into the new regime), which were based on a vast array of spies (hafiye), as well as constant interventions by the European powers to the point of endangering the Empire's sovereignty.

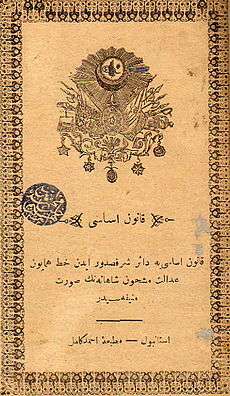

The legal framework was that of Kanûn-ı Esâsî of the First Constitutional Era that had prevailed in 1876. Since the sultan declared that he had never officially dissolved first Ottoman Parliament, the former parliamentarians (those still able to serve) who had gathered 33 years before suddenly found themselves representing the people again at the restoration of constitutionalism.

As in 1876, the revived Ottoman Parliament consisted of two chambers: a Senate (upper house) and a Chamber of Deputies (lower house). The Chamber of Deputies was elected by the people, in the ratio of one member for every 50,000 males of the population over the age of 25 who paid taxes. Senators, on the other hand, were nominated for life by the Sultan, had to be over 40 years of age, and their number could not exceed a third of the membership of the Chamber of Deputies.

General elections were to take place every four years. The general population did not, however, vote directly for the Deputy that he desired to represent him in the Parliament. In each of the 15 electoral districts, registered voters were entitled to choose delegates in the proportion of 1 delegate for 500 voters, and these delegates (elected Administrative Councils) had the actual power of choosing the representatives in the Chamber. Moreover, the administration of territories was entrusted to these delegates in the elected Administrative Councils. Thus, these Councils were elected and served not only as an electoral college, but also as a local government in the provinces and districts (Turkish: vilayets).

The parliament convened after the revolution only briefly and rather symbolically. The only task they performed was to call a new election. In the first Parliament, the president of the Chamber of Deputies was a Deputy from Jerusalem, Yusif Dia Pasha Al Khalidi.

First term, 1908

The new parliament comprised 142 Turks, 60 Arabs, 25 Albanians, 23 Greeks, 12 Armenians (including four Dashnaks and two Hunchaks), 5 Jews, 4 Bulgarians, 3 Serbs and 1 Vlach in the elections of 1908. The CUP could count on the support of about 60 deputies.[1] The CUP, the main driving force behind the revolution, managed to gain the upper hand against the Liberal Union (LU). LU was liberal in outlook, bearing a strong British imprint, and closer to the Palace. CUP come as the biggest party among a fragmented parliament by only 60 of the 275 seats.

On 30 January 1909, the minister of the interior, Huseyin Hilmi Pasha, took the podium to answer an inquiry sponsored by both Muslims and non-Muslims, all but one of whom were from cities in the Balkans. It was about how the government would deal with what these deputies called lacking of the law and order; the rise of assassinations and armed assaults; the roaming of bandits. Ethnic and sectarian violence between various communities in the empire was costing both lives and resources. This was an important event as the newly established system was passing the first test regarding the "proper" parliamentary conduct. There were members of various diplomatic missions among the audience. The new constitution secured the freedom of the press, newspapermen and other guests were observing the proceedings. The first section of the protocol (minister's speech, deputies oppositions) achieved. However arguments began to break out between deputies and soon all decorum was cast aside, the verbal struggle was representation of the ethnic troubles plaguing the empire. The interchanges were performed along the nationalism lines among the non-Muslim deputies, according to their ethnic and religious origins, and of Ottomanism as a response to these competing ideologies.

31 March Incident, 1909

Threats to the experiment in constitutional and parliamentary government soon appeared. Nine months into the new parliamentary term, discontent and reactionary sentiment against constitutionalism found expression in a fundamentalist movement named as the Ottoman countercoup of 1909.

The countercoup ultimately resulted in the counter-revolutionary 31 March Incident (which actually occurred on 13 April 1909). The constitutionalists were able to wrestle back control of the Ottoman government from the reactionaries with the "Army of Actions" (Turkish: Harekat Ordusu). Many aspects of 31 March Incident, which started within certain sections of the mutinying army in Istanbul, are still yet to be analyzed.

The popularly-elected Chamber of Deputies met in secret session two days later and voted unanimously for the deposition of Abdul Hamid II. His younger brother, Mehmed V, become the new Sultan. Hilmi Pasha again became grand vizier, but resigned on 5 December 1909, when he was succeeded by Hakki Bey.

Constitutional revision, August 1909

The CUP was again in power. Holding that the countercoup had been inspired and organized by the Sultan, who had corrupted the troops so that he might restore the old regime, they resolved to terminate his rule. This was achieved by removing the powers of the Sultan from the constitution and removing him from the throne. This served to largely remove the remaining threats to the parliament and constitutionalism.

The new constitution banned all secret societies. Parliament was prorogued for three months on the 27th. During the recess, the CUP met at Salonica and modified its own party rules. The CUP ceased to be a secret association. This was regarded as an expression of confidence in the reformed parliament, which had laid the foundation of the important financial and administrative reforms.

Policies

Tensions and clashes arose between Zionists and Palestinian farmers near Nazareth. A Palestinian deputy from Jaffa raised the Zionist issue for the first time in Ottoman parliament.

Once in power, the CUP introduced a number of new initiatives intended to promote the modernization of the Ottoman Empire. CUP advocated a program of orderly reform under a strong central government, as well as the exclusion of all foreign influence. CUP promoted industrialization and administrative reforms. Administrative reforms of provincial administration quickly led to a higher degree of centralization.

Although the CUP collaborated with the LU, their respective goals contrasted strongly. LU favored administrative decentralization and European assistance to implement reforms and also promoted industrialization. In addition, the CUP implemented the secularization of the legal system and provided subsidies for the education of women, and altered the administrative structure of the state-operated primary schools. The new parliament sought to modernize the Empire's communications and transportation networks, trying at the same time not to put themselves in the hands of European conglomerates and non-Muslim bankers.

Germany and Italy already owned the paltry Ottoman railways (5,991 km of single-track railroads in the whole of the Ottoman dominions in 1914) and since 1881 administration of the defaulted Ottoman foreign debt had been in European hands. The Ottoman Empire was virtually an economic colony.

Towards the end of 1911, the opposition gathered around the re-organized LU (now officially founded as the Freedom and Accord Party in November 1911) seemed on the rise. Only 20 days after formation, a by-election in December 1911 (actually covering a single constituency) in which the Liberal Union candidate won was taken as a confirmation of a new political atmosphere and its repercussions were extensive. By 1912, the Committee of Union and Progress had been in power for four years.

Second term, 1912

The period of 1912–13 was a highly turbulent time for the Ottoman government in terms of both domestic and foreign affairs. It marked a political power struggle between the Committee of Union and Progress and the Freedom and Accord Party (also known as the Liberal Union or Liberal Entente), consisting of rapid exchanges of power involving a rigged election, a military revolt, and finally a coup d'état on a background of the disastrous Balkan Wars.

"Election of Clubs" and CUP government

The CUP now called for early national elections in order to thwart the new Freedom and Accord's ability to better organize and grow.[2] In the two-party general elections held in April 1912, nicknamed the "Election of Clubs" (Turkish: Sopalı Seçimler) because of the widespread electoral fraud and violence engaged in by the CUP against Freedom and Accord candidates, the results showed that CUP won an overwhelming majority (269 of 275 seats in the Chamber of Deputies).[2] A cabinet of CUP members was formed under Grand Vizier Mehmed Said Pasha.

Savior Officers' revolt and LU government

Angered at their loss in the election, the leadership of Freedom and Accord (LU) sought extra-legal methods to regain power over the CUP, complaining vocally about electoral fraud. At around this time, a group of military officers, uncomfortable with injustices it perceived within the military, organized itself into an armed organization known as the "Savior Officers" (Turkish: Halâskâr Zâbitân) and made their presence known to the imperial government.[3] The Savior Officers, quickly becoming partisans of Freedom and Accord, soon created unrest in the capital Istanbul. After gaining the support of Prince Sabahaddin,[4] another opposition leader, the Savior Officers published public declarations in newspapers.

Finally, after giving a memorandum to the Military Council, the Savior Officers succeeded in getting Mehmed Said Pasha (who they blamed for allowing the early elections that led to the CUP domination of the Chamber)[2] and his government of CUP ministers to resign in July.[5][6] Mehmed Said Pasha was succeeded by the non-partisan government of Ahmed Muhtar Pasha (the so-called "Great Cabinet", Turkish: Büyük Kabine).[7] With the support of the Savior Officers, Ahmed Muhtar Pasha also dissolved the Chamber, which was still full of CUP members, and called for new elections on 5 August. The eruption of the Balkan War in October derailed plans for the elections, which were canceled, and Ahmed Muhtar Pasha resigned as Grand Vizier.

The new Grand Vizier, the LU's beacon Kâmil Pasha, formed a LU cabinet and began an effort to destroy the vestiges of the CUP government remaining after the Savior Officers' revolt.[2]

Using his friendly relations with the British, Kâmil Pasha also sat down to end the ongoing First Balkan War diplomatically. However, the heavy Ottoman military upsets during the war continued to sap morale, as rumors that the capital would have to be moved from Istanbul to inland Anatolia spread.[8] The Bulgarian Army had soon advanced as far as Çatalca, a western district of modern Istanbul. At this point, Kâmil Pasha's government signed an armistice with Bulgaria in December 1912 and sat down to draw up a treaty for the end of the war at the London Peace Conference.

The Great Powers–the British Empire, France, Italy, and Russia–had begun to engage in the relationship of Bulgaria with the Ottoman Empire, citing the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. The Great Powers gave a note to the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman government) that they wanted the Ottoman Empire to cede Edirne (Adrianople) to Bulgaria and the Aegean islands under its control to the Great Powers themselves. Because of the losses experienced by the army so far in the war, the Kâmil Pasha government was inclined to accept the "Midye-Enez Line" as a border to the west and, while not outright giving Edirne to Bulgaria, favored transferring control of it to an international commission.[9]

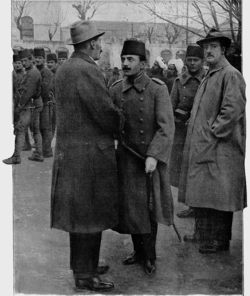

Coup of 1913 and CUP government

The LU government with Kâmil Pasha as the Grand Vizier was overthrown in a coup d'état (also known as the Raid on the Sublime Porte, Turkish: Bâb-ı Âlî Baskını) engineered by CUP leaders Enver and Talaat Bey, who used the pretext of Kâmil Pasha "dishonoring the nation" by allegedly agreeing to give away Edirne to the Bulgarians. On 23 January 1913, Enver Bey burst with some of his associates into the Sublime Porte while the cabinet was in session, a raid in which the Minister of War Nazım Pasha was killed. A new CUP government was formed, headed by Grand Vizier Mahmud Shevket Pasha.

Mahmud Shevket Pasha was assassinated on 11 June 1913 in revenge by a relative of Nazım Pasha, although he was genial towards the now-opposition LU after the coup. After his death, he was succeeded by Said Halim Pasha, and CUP began to repress LU and other opposition parties, forcing many of their leaders (such as Prince Sabahaddin) to flee to Europe.

Policies

After the Balkan Wars, Ottoman Empire became an entity with two major constituents; namely Turks and Arabs. In the new framework, the percentage of representatives from Arab provinces increased from 23% (1908) to 27%, Turkomans 14% (1908) to 22% and in total CUP members from 39% (1908) to 67%.

In the new consolidated structure minority issues, such as those affecting the Armenians, dominated mainstream politics. Armenian politicians were supporting the CUP, but when the parliament was formed the result was very different from the expected one. The Balkan wars had significantly shifted from a multiethnic and multireligious Ottoman Empire to a Muslim core. The size of the CUP's majority in parliament proved to be a source of weakness rather than strength as minorities became outsiders. The deported Muslims (Turks) from the Balkans were located in the western parts of Anatolia and they brought their own issues. Armenians were expecting more representation through the parliament, but the nature of democracy kept them in a minority position. That was an unexpected result for the Armenians after they had been in a protected position since 1453.

In 1913, politics in Istanbul was centered around finding a solution to the demands of Arab and Armenian reformist groups. 19th century politics of Ottoman Empire dealt with the decentralist demands of the Balkan nations. In 1913, the same pattern was originating from the eastern provinces. With most of the Christian population having already left the Empire after the Balkan Wars, a redefinition of Ottoman politics was in place with a greater emphasis on Islam as a binding force. The choice of this policy should also be considered as external forces (imperialists) were Christians. It was a policy of "them against us".

Grand Vizier June 1913 -February 1917

Minister of the interior January 1913– February 1917

Minister of War January 1913–October 1918

Minister of Navy January 1913

Third term, 1914

Taking account of the loss of the Balkans and of Libya for the Ottoman Empire and despite the single-party regime installed by the CUP, the Ottoman ethnic minorities were going to be represented at similar proportions during the 1914-1918 term of the Ottoman Parliament, with 11 Armenians and a dozen Greeks being elected as deputies and having served in that capacity.[1]

New elections in a single-party framework were held in 1914 and the CUP gained all constituencies. The effective power lay in the hands of Mehmed Talat Pasha, the Interior Minister, Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, and Cemal Pasha, the Minister of the Navy, till 1918. Talat Pasha became the grand vizier himself in 1917.

A fraction within the CUP led the Ottoman Empire to make a secret Ottoman–German Alliance which brought it into World War I. The Empire's role as an ally of the Central Powers is part of the history of that war. With the collapse of Bulgaria and Germany's capitulation, the Ottoman Empire was isolated.

Fourth term, 1919

The last term elections were performed under the military Occupation of Constantinople by the Allies, but they were called under the Amasya Protocol signed on 22 October 1919 between the Ottoman government and the Turkish National Movement, in order to agree on a joint Turkish resistance movement against the Allies.

When the new session of the Chamber of Deputies convened on 16 March 1920, it passed the Misak-ı Millî (National Pact) with the Turkish National Movement, angering the Allies. Several MPs were arrested and deported. The Allies forced sultan Mehmed VI and he dissolved the parliament on 11 April.[2]

End of CUP, 1919

On 13 October 1918, Talaat Pasha and the rest of the CUP ministry resigned, and the Armistice of Mudros was signed aboard a British battleship in the Aegean Sea at the end of the month. The Turkish Courts-Martial of 1919–20 took place where the leadership of the Committee of Union and Progress and selected former officials were court-martialled under charges of subversion of the constitution, wartime profiteering, and the massacres of both Armenians and Greeks.[10] The court reached a verdict which sentenced the organizers of the massacres, Talat, Enver, Cemal and others to death.[11][12] On 2 November, the Three Pashas (Talaat, Enver, and Djemal) escaped from Constantinople into exile.

Occupation issues, January 1920

The last elections for the Ottoman Parliament were held in December 1919. The newly elected 140 members of the Ottoman Parliament, composed in their sweeping majority of candidates of "Association for Defense of Rights for Anatolia and Roumelia (Anadolu ve Rumeli Müdafaa-i Hukuk Cemiyeti)", headed by Mustafa Kemal Pasha, who himself remained in Ankara, opened the fourth (and last) term of the Parliament on 12 January 1920.

National Pact, February 1920

Despite being short-lived and the exceptional conditions, this last assembly took a number of important decisions that are called Misak-ı Milli (National Pact). It had signed the Amasya Protocol with the Turkish National Movement in Ankara on 22 October 1919, in which the two groups of agreed to unite against the Allies occupying the country and call for these elections. At the Protocol, the Ottoman government was represented by Minister of the Navy Salih Hulusi Pasha, and the Turkish National Movement was represented by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Rauf Orbay, and Bekir Sami Kunduh in their title of Delegation of Representatives (Heyeti Temsiliye).[2]

Dissolution, March 1920

On the night of 15 March, British troops began to occupy the key buildings and arrested five parliament members. The 10th division and military music school resisted the arrest. At least 10 students died under the gunfire of the British Indian army. The total death toll is unknown. Nevertheless, on 18 March, the Ottoman parliamentarian came together in a last meeting. A black cloth covered the pulpit of the Parliament as reminder of its absent members and the Parliament sent a letter of protest to the Allies, declaring the arrest of five of its members as unacceptable.

In practical terms, the meeting of 18 March, was the end of the Ottoman parliamentarian system and of the Parliament itself, the noble symbol of a generation's quest for "eternal freedom" (hürriyet-i ebediye) for which men had sacrificed themselves. The British move on the Parliament had left the Sultan as the sole tangible authority in the Empire. The Sultan announced his own version of the declaration of the Parliament's dissolution on 11 April. About 100 Ottoman politicians were sent to exile in Malta (see Malta exiles).

More than a hundred of the remaining members soon took the passage to Ankara and formed the core of the new assembly. On 5 April, the sultan Mehmed VI Vahdeddin, under the pressure of the Allies, closed the Ottoman parliament officially.

See also

- First Constitutional Era (Ottoman Empire)

- Committee of Union and Progress

- The Ottomans: Europe's Muslim Emperors

Footnotes

- 1 2 Philip Mansel, "Constantinople City of the Worlds Desire" quoted in Straits: The origins of the Dardanelles campaign

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kayalı, Hasan (1995). "Elections and the Electoral Process in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1919" (pdf). International Journal of Middle East Studies. 27 (3): 265–286. doi:10.1017/s0020743800062085.

- ↑ Aymalı, Ömer (23 January 2013). "Modern dönemin ilk askeri darbesi: Bab-ı Âli baskını". dunyabulteni.net. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ "Liberaller bu yazıya kin kusacak" (in Turkish). odatv.com. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ Birinci, Ali (1990), Hürriyet ve İtilâf Fırkası: II. Meşrutiyet Devrinde İttihat ve Terakki'ye Karşı Çıkanlar (in Turkish), Istanbul: Dergâh Yayınları, pp. 164–177, ISBN 9759953072

- ↑ Dumont, Paul; Georgeon, Gregoire François; Tanilli, Server (1997), Bir İmparatorluğun Ölümü: 1908–1923 (in Turkish), Istanbul: Cumhuriyet Yayınları, p. 56

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard (1961). The Emergence of Modern Turkey. Ankara.

- ↑ Şimşir, Bilal. "Ankara'nın Başkent Oluşu". atam.gov.tr. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ Kuyaş, Ahmet (January 2013), "Bâb-ı Âli Baskını: 100. Yıl", NTV Tarih (in Turkish) (48): 26, ISSN 1308-7878

- ↑ Akçam, Taner (1996). Armenien und der Völkermord: Die Istanbuler Prozesse und die Türkische Nationalbewegung (in German). Hamburg: Hamburger Edition. p. 185.

- ↑ Herzig, edited by Edmund; Kurkchiyan, Marina (2005). The Armenians past and present in the making of national identity. Abingdon, Oxon, Oxford: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0203004930.

- ↑ Andreopoulos, ed. by George J. (1997). Genocide : conceptual and historical dimensions (1. paperback print. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812216164.

External links

- Short history of elections under the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey by Turkish Industrialists and Businessmen's Association (Turkish)

- Incomplete list of Ottoman deputies in 1908-1912 term - in Turkish

- List of Ottoman deputies in April–August 1912 term - in English or in Turkish

- Incomplete list of Ottoman deputies in 1914-1918 term - in Turkish

- Incomplete list of Ottoman deputies in January–March 1920 (last) term; official closure April 1920; - in Turkish

_p259_Sultan_Abdul_Hamid_II.jpg)